As told to Trish Connelly, 2038 words.

Tags: Animation, Art, Process, Collaboration, Focus, Production.

On expanding how you do what you do

Cartoonist and animator Dash Shaw discusses the intentional nature of animation and film, drawing inspiration from collages, and collaborating with time.Your themes in Cryptozoo and your graphic novels seem to focus on surreal and dream-like states. What draws you toward these subjects in your work?

It could be that they all involve drawing. I feel like drawing can be a direct circuit to the imagination and imaginary worlds and it’s not tethered to reality. The classic thing of a kid doodling, they’re inventing and dreaming on paper.

That makes sense with illustrations and having an open space to allow that creative channel to come through. When working with intentional and slower paced mediums like animation, film, and graphic novels what is your process like when creating a storyboard before a project? How do you know when a project is complete?

They are the two slowest mediums one could pick in terms of the amount of time that you put into them, equaling how fast they go by. That dissonance is helpful for me because I’m naturally an impatient person and I’m kind of fighting it the whole time. The main collaborator ends up being time because you can look at something that you did three months ago and reassess if you still like it or want to redraw it. At each stage, screenwriting, storyboarding, drawing the figures or whatever, there’s a natural editing process of having to do the work of recreating it. It’s hard to have an immediate component in them. You can draw something quickly, but it ends up being part of a much bigger story, and the drawing has to function inside of a big thing. Chris Ware would describe it as “cabinet making.”

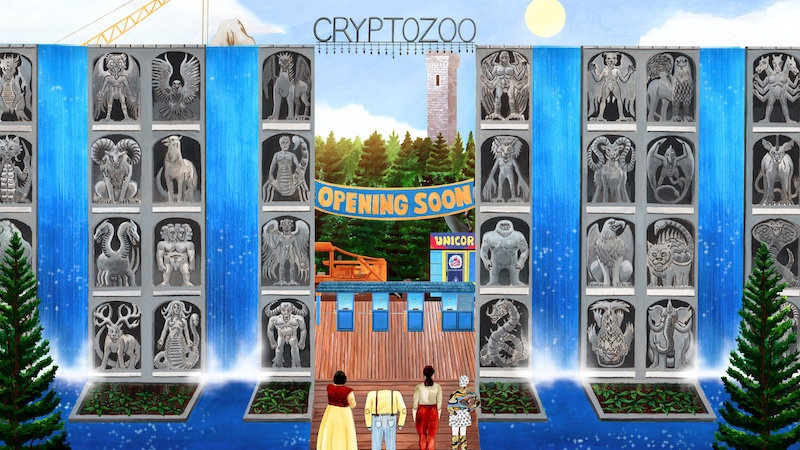

a still from Cryptozoo

In terms of completing a project, does that vary for you? Is there a way when you know it’s finished?

My books usually don’t have a deadline. With the movies, you submit to a festival and that ends up becoming the deadline. You have the hope that it’ll be done at a certain time, but none of my movies have ever actually hit that goal. So knowing when it’s done, that’s a really, really hard question. I wish I had a good answer for you. Discipline, the book I did that’s coming out later this year, I worked on for a very, very long time from 2014 to 2020. It got to be that the redrawing elements only created more problems and inconsistencies in it. I had passed some line. With drawing you’re like, “Okay. You add lines, of course,” and then at some point you’re like, “Okay, now you take lines away.” And then you kick it down. So knowing where that line is, is really hard.

I imagine it’s a very open space or might vary from project to project when you reflect back on it.

I would love to be able to make things more immediately. Because with Cryptozoo, entering into it, it had to hold a lot of stuff because it had to be interesting for so many years and executing the different parts of it. Some of my favorite movies have a very “tossed off” quality. The Fassbender movies are a great example of that. Maybe there’s some of that energy with the figure drawings in Cryptozoo, but it’s really hard to get that in an animated movie.

a still from Cryptozoo

Have you thought about working in any artistic realms that might have more of an immediate pacing in the future?

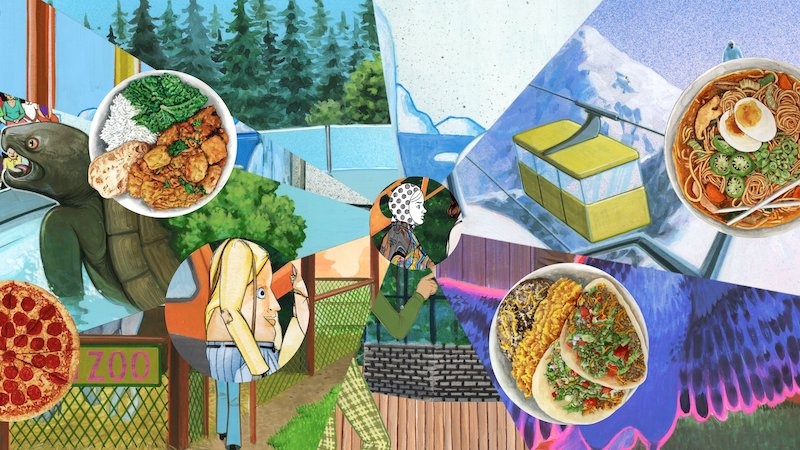

I like to make little drawing collages that I would post on Instagram. Those I could do in a day. And those are really fun.

I had read in a previous interview that you draw a lot of inspiration from collages. What is that process like? How do you put those collages together?

The collage art to me is about the relationships between things. I think with a good collage, each of the pieces are separate and then unexpected connections occur that opens your mind and is inspiring. Even in words, like John Ashbery poems, there’s unfinding things, [assuming] the words rhyme. There’s already a connection, but the content of it is so unusual that you’re seeing potential connections between things. It’s your brain firing connections at night and making associations. So much of my favorite work ultimately has some kind of collage quality.

Like taking two seemingly distinct ideas or subjects and connecting them in a way that might not have come together prior to the collage process.

Yeah. The first stretch of James Rosenquist paintings are very bold, often only having a few elements. They have a great mood and his sensibility is in it, even though they’re coming from different sources that he’s altering. Comics are like collages that are given rules where you have to start in the upper left-hand corner and go to the bottom right. But if a panel is bigger you’re saying it’s more important than the other panels. That’s a collage rule. My movies become a collage of the different actors and the different artists involved. And how you retain their voice but have it add up to something bigger that isn’t just a bunch of stuff that is orchestrated.

I noticed you worked with a few of the same voice actors in your debut film, My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea. Do you prefer working solo versus working in a collaborative sense?

In my animation films the main collaborator is Jane, my wife, who really figured out the animation, particularly in Cryptozoo. The collaborative aspect of it was not natural to me. I had to figure out how to do it through a desire to make these limited cartoons. I spent years slowly getting better at that part of it. My more natural self is more like a cartoonist that doesn’t have to talk to anybody, but it definitely makes my life more interesting to have to try to make these [collaborative projects]. Especially with alternative cartoonists, you can really be someone in your radio tower sending the signal out and not have to step outside the radio tower. You don’t have to watch someone reading your comic, confused why you did this, that and the other. You can separate yourself from being aware of how the signal is being received.

With animation, even my projects, which are quite small, you have to explain every single part of your process. Why you’re starting the movie this way and not that way. Why the score should be like this and not like that. You’re constantly having to articulate these things. Then when you see it screened, you can tangibly feel people’s boredom or confusion at different moments. You can see why so many movies are very literal and emotionally locatable because if you have a comedy and you hear the people laugh, you get a great high immediately. Then you’re like, “This movie is working. I wanted to get a laugh and I got a laugh.” That’s success. For me the goal is not so locatable. It’s usually something in an in-between space that makes it a little harder to know if the signal is reaching the destination.

The process of Cryptozoo was started pre-pandemic and continued during the pandemic. Did that interfere any with the collaborations with the people working on the film or did it change the trajectory of where the film went?

One of the big things was the score. I am not a musical person and I live in Richmond, Virginia, so I feel quite removed from everything. I knew that this movie had to have a lot of music and the score had to be really surprising and exciting. If I went to see an adult animated movie called Cryptozoo it would have to have a totally incredible score. It would be a huge disappointment if it didn’t.

This guy named Rick Alverson [in Richmond] put me in touch with the label Jagjaguwar. I called them over the phone and described Cryptozoo to them and the first person they thought of was John Carroll Kirby. He had never scored a movie before, but I loved his album Travel. I thought it was perfect for Cryptozoo. Years later, when the movie was ready, he had made more albums and was touring even more and had become well-known. Then the pandemic struck and his tours were canceled and he was stuck at home. So we got him. It was quarantine, all he could do was score our movie. So in that sense it worked out for us. We did our main voice recordings pre-pandemic, and then pick up voices were done during the pandemic.

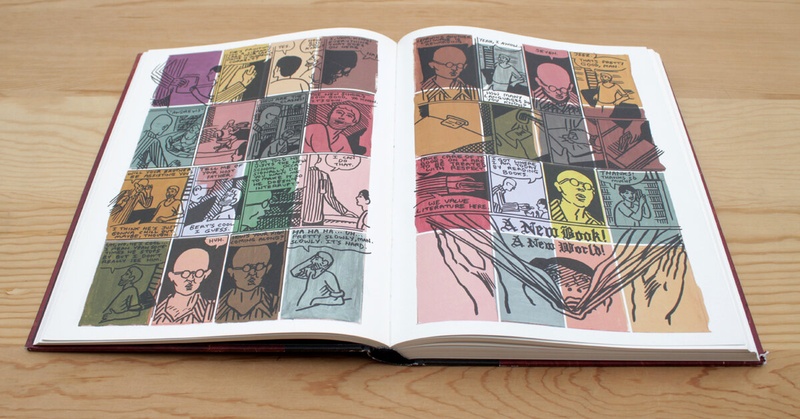

from New School

Your use of color is very noticeable, especially in works like Cryptozoo and New School. What’s your process like in terms of using color or the lack of it in your films and graphic novels?

When I was a teen in the ’90s and in the School of Visual Arts, I majored in cartooning. So much of the alternative comics then were in black and white, or if they were in color it was like the Chris Ware school of [naturalist] coloring. And then there were silkscreen comics, where two colors combine to create a third color. It felt like color was an unexplored area to add meaning to a comic. So I did a lot of comic stories where some of them appeared in Mome, the Fantagraphics anthology, where it’s like color coding. It was expressive coloring that aligned in an unusual way that adds content to the comic.

It definitely popped out as a very distinct choice and vision when I’ve read your graphic novels and watched Cryptozoo.

When New School came out I was totally on cloud nine. It felt really, really exciting because it felt like discovering something and following it. Like following your own trail for a very, very long time. The way that book is drawn, it could hold different colors. The lines were thick enough that you could put very extreme color underneath it and it would still be legible.

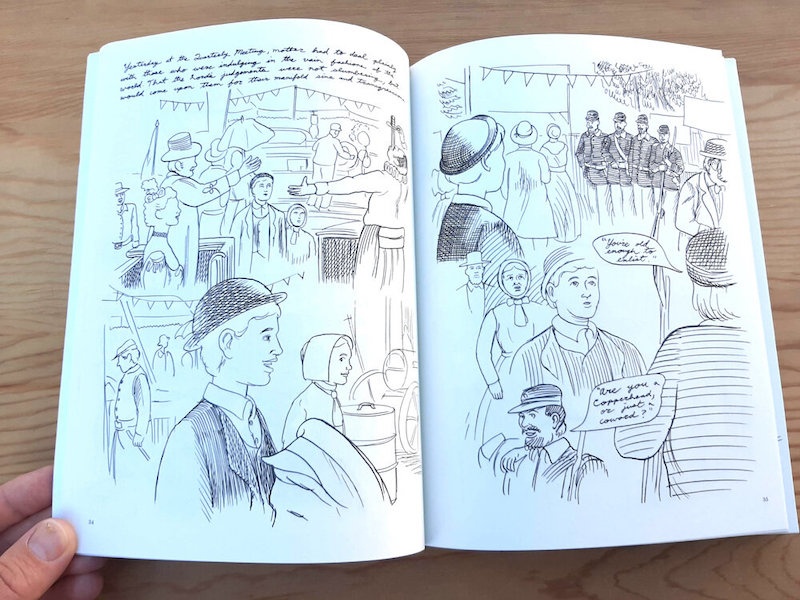

from Doctors

In terms of creative burnout, are there ways that you are able to resist falling into that or are there any techniques you lean into?

This is a bit of a cop-out answer but there are enough different things involved in making animated movies that you can change gears. Especially for me, normally the director isn’t also the person painting the backgrounds. So it can be almost like schizophrenia when you’re trying to write something and then stop and be like, ‘Okay, how do I paint this grass in this suburban neighborhood?’ There are definitely quick techniques that you can pick up from watching older cartoonists where they have to execute something quickly, but then even that brain is very different than writing an email trying to get an actor involved. I think that’s also why I said that it makes my life more interesting to try to do these things. If I was only making the books I wouldn’t have gotten to exercise all these other different kinds of muscles.

That makes sense. Instead of going on one path and finding a creative block, there are several others you can take that don’t utilize the same way of thinking. In terms of someone interested in delving into the animation world, what advice would you give to them?

The fantastic thing about comics is that it’s quite accessible to make and to distribute. You don’t need an agent, you can just draw something and go to a comic convention and hand it to a publisher. You can learn about storytelling very quickly and be drawing things consistently. It can be very independently produced.

Dash Shaw recommends:

Graphic novels from Gilbert & Jaime Hernandez:

from Discipline