As told to T. Cole Rachel, 2348 words.

Tags: Art, Music, Multi-tasking, Failure, Mental health.

On working every angle

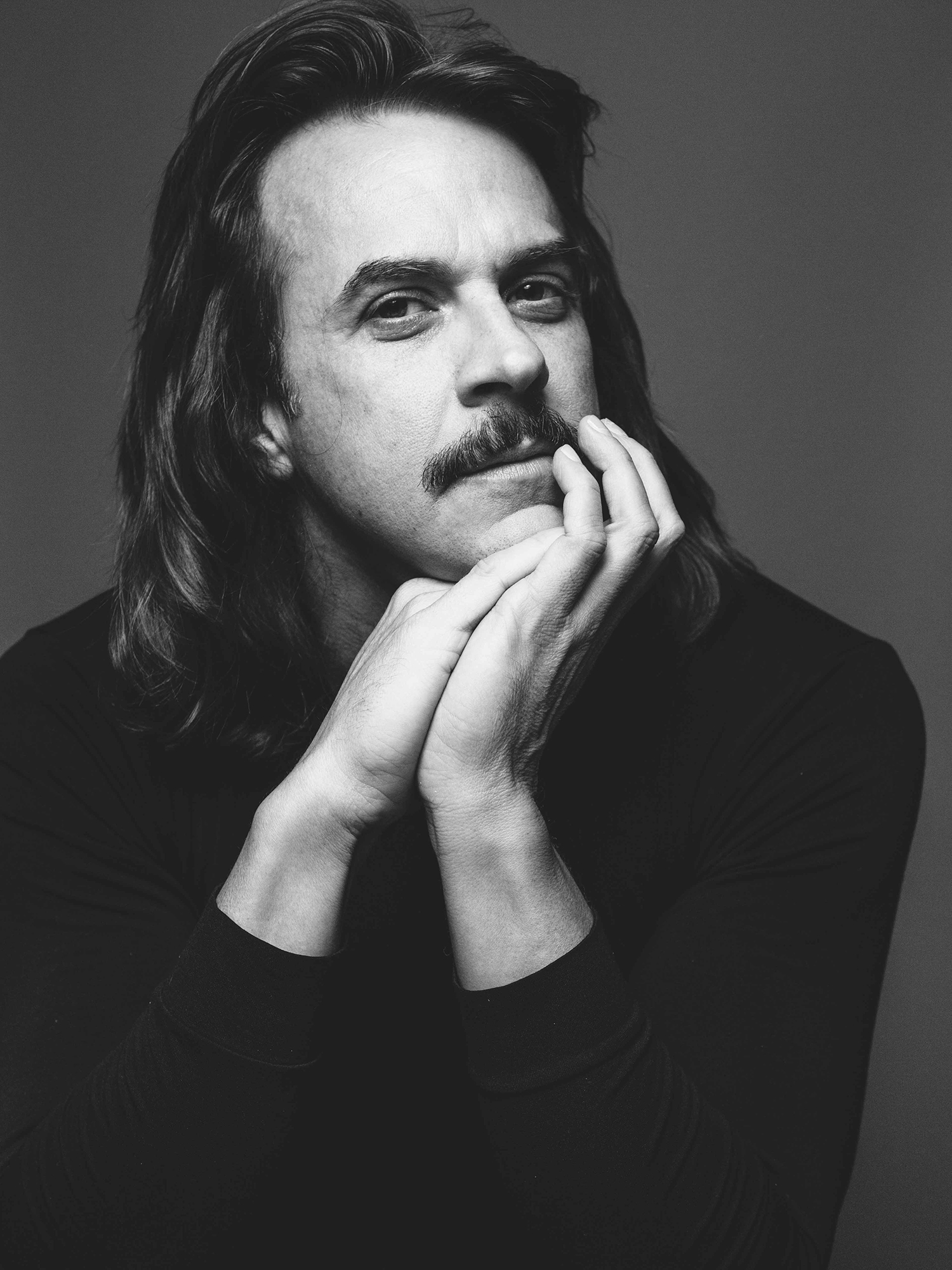

Musician and visual artist Casey Spooner on leaving (and coming back to) the music industry, navigating between creative worlds, and letting your interests and intuition lead the way.When people who don’t know anything about you ask you what you do for a living, what do you tell them?

I just say I’m an artist. For a long time I really deliberated over what to call myself and how to define it, but it’s simpler to say I’m an artist. Always when I go through customs, they’re like, “What? Who the hell are you, in that insane fur coat?” And I’m like, “I’m an artist.” Their jaw drops, because they’re like, “How can you be so fabulous and be an artist?” You can tell they’re like, “I want your job!”

People will often say, “Oh, so you’re a painter?” First thing, everybody always thinks if you’re an artist, you’re a painter, which is what I always thought I was going to be when I grew up, but no. So now I say, “I’m an artist and I work between film, photography, music, and performance.” All those things can be interrelated, and I may be in them and I may not be, but I move between those four things.

You’ve spent the better part of 2018 performing and traveling in support of Sir, the first new Fischerspooner record in almost a decade. I know you stayed busy doing lots of different things during the interim, but was there a time when you doubted whether or not you would ever make music again?

Absolutely. After Entertainment I felt done with music completely. That release was so botched, and the labels were a mess, and management was a mess, and touring was a mess, and I lost a fortune, and I spent over three years making something and it kind of didn’t go anywhere. Then I accidentally made a solo record with the same producer, but then that didn’t get any traction because it was aesthetically too far away from what people expected of me. And because the previous record didn’t take off, that kind of killed the second record. I’d made four records at that point and I was just like, “I’m done.”

After that I went back and started doing more work with the Wooster Group, which I love, and then I made a film with Adam Dugas, we co-wrote and co-directed a feature that was shot in Kansas City, and that I was very hopeful for. That felt very good, like a new direction we were going to go in. For some reason, there was a lot of interest and we did a lot of screenings, but it never really took off. And then I can’t remember. I started doing a lot of photo projects where I was sitting for a lot of photographers, and I didn’t really know why. At some point in there I spent about a year and a half putting together a book about Fischerspooner, and then they wanted me to do another book.

So you know, I made a movie, I did two plays, I did two books. I also did a series of portraits of different creatives, in a way it was similar to what you’re doing at The Creative Independent. I did that for a year. I made about two videos a month for a year, interviewing different creative people—a real range of people that were both well known and lesser known. That was fun. It was almost like a healing thing for me because I was so wounded at that point. It felt incredible to go and spend a year talking to other creative people, and figure out how they dealt with the creative process, and how they dealt with their career. It was like I did a kind of a great survey. Looking back on it, it was a kind of therapy.

I’m always fascinated by people who are self-created, who can follow their impulses wherever that leads them, who can do lots of different kinds of things, and who don’t appear daunted by trying things that are perhaps outside their own realm of expertise. Has that always been your approach to things?

Yeah, pretty much. You know, I’ve been working on a museum show that will open in Germany and then hopefully travel around. One of the projects evolved form a photo shoot that happened in my apartment, which then became a music video, a single, a video sculpture, a book, and a show. We started with one thing and it eventually just became all of these other things. It’s the idea that defines the work to me, not the medium. The idea can travel. The idea can be text, the idea can be a song, the idea can be motion, the idea can be film. So it’s very natural, to me, to kind of float between all those things, because the idea is the same. Once you have the core idea, then it’s easy for it to travel between forms. I don’t think too much about “Is this something I can do?” and usually just assume that I’ll be able to figure it out.

You collaborated with Michael Stipe on the new record, but over the years you have worked with lots of different kinds of people in lots of different creative spheres. What makes for a good collaborator or a good collaboration?

I don’t know, to be honest. I connect with different people in different ways. I tried to be a painter and I just couldn’t do it because it was too solitary. I’m a very social person. I love going to rehearsal and I love going to the studio. Being submerged in the actual process is really the way I like to live. I like to learn, but I’m a terrible student, and the only way I learn things is by watching other people and by example. So I feel like I’m always learning and growing when I’m working with other people. As opposed to working alone.

I also am pretty good at not having too much ego about making something. I don’t feel like I have to fight for it. I believe in good ideas and if they coalesce between different perspectives, that’s a good thing. That’s the most important thing, actually: that people are confident enough and free enough to allow something to happen between each other and not get too territorial about what’s a good idea.

I also totally let go of the idea that there’s a right way and there’s a wrong way. There are just different ways. That’s something that I really find great about digital culture and online culture, it allows for that. For instance, Warren and I did two different edits of the “Togetherness” video, and there was a debate as to which video was better. At a certain point I was like, “It doesn’t matter. It’s digital. Release your version and release my version. And then it’s cool because you see two different perspectives on it.”

We also did two versions of “Have Fun Tonight.” A version that’s way more poppy, and then there’s a version that’s a little bit more chill. I’m already thinking about releasing that one later as a different version. There’s kind of a cool thing we live through now. One of the positives of how cheap and easy and accessible digital content is—also, I hate that word content—but with digital “stuff” you can easily share all these different versions. That sort of takes the battle away, at least for me, about ownership and always having the singular version. The idea of singularity is over.

Back when you first started Fischerspooner it was groundbreaking in the sense that it really defied definition—it wasn’t necessarily pop music…or dance…or performance art, and yet it was all of those things. Has your idea about that changed over the years? And is there something you wish you had been more cognizant of when you were younger and starting to make things?

I’ve always felt the same way about art and music. I’ve always been open and fluid. I didn’t really care about how what I did was defined. In the past I learned that it didn’t matter how I thought, but sometimes it really did matter what other people thought and how they defined it. When we were having a lot of success in the art world, which really was where I wanted to be, we had a gallery and lots of exhibitions. We had a lot of support, and we had a lot of interest, and it felt like we really were establishing ourselves in the art world. It was this cool hybrid between art and entertainment.

And then the music business showed up and started getting more and more interested. I tried to build a dual career between art and entertainment, and it did not work at all. I could not get the art world and the entertainment world to work in tandem. I couldn’t’ get them to share budgets, I couldn’t get them to communicate with each other. I couldn’t get them to communicate in terms of scheduling. So really for this record, over a decade later, I’m now able to have the art world in contact with the entertainment world, and they’re working in tandem with each other for the first time. When I tried to do that in 2002, it did not work. The music people were really threatened by the art people, and the art people were really condescending and rude to the music people. There was all this stupid friction between these idiots because they were so dumb and territorial and they weren’t really focused on the bigger idea.

I get it now. It made sense in terms of a market and how the markets work. An art market is built on exclusivity and controlling access to the product, while show business is built on being as pervasive and as as accessible and as popular as you can possibly be. Trying to generate creative work that could somehow enable both of those things was nearly impossible back then. Now I feel like I get it. I can take a photograph and use it for the cover of a single, but then take the entire shoot that image came from and turn it into a museum show.

So really, what I’m doing now is what I always intended, but for some reason it wasn’t possible to do it 15 years ago. People weren’t open to the idea. I don’t know why. It was incredibly frustrating. I thought my ideas were strong enough to transcend all of that. I thought ideas could rule the world, but I was naïve. I thought I could be a post-Warhol-ian jack of all trades. It just proved to be very difficult. In hindsight what I would say is that you should choose the thing that has the most power and the most access to resources, commit to that direction, build that identity and that career, and then you can take that money, that power, those resources and shift between economies to do whatever you want.

Back then I positioned myself perfectly, I put myself right in the middle, and the whole thing imploded and failed. And then I was just lost. The entertainment business didn’t want to touch me and the art world didn’t want to touch me. I was a pariah. It took me a long time to circle back, to figure out a new way forward. Now everybody wants to touch me.

When you are caught in a moment like this, in which you are juggling a variety of projects and trying to capitalize on a certain kind of energy and attention, how do you keep up? How do you not burn out?

It’s always unfolding. I have moments where I’m like, “Oh my god, how the hell am I going to pull off all these things at the same time?” It’s also that cliché, when it rains, it pours. There was nothing to do for the past two years other than work on the record. I’ve been sitting on my hands having a nervous breakdown. Alone. Waiting for this record to come out. And now all of a sudden that it’s out, it’s like, I have to do a trillion, million, billion things all at once.

I love working in film and when I write music, I have very clear conceptual ideas—not just about the words, but about locations and images. I’m going to keep shooting as many music videos as I can, and I love to perform. I’ll go wherever people want me. I’ll always move towards whatever inspires me, whatever feels fun and interesting and exciting. That is something that will never change.

The great thing is, I’ve been planning and developing ideas and making pitches and shooting. I knew this was going to happen. Even when there was nothing going on, I was still getting ready. And now that the gun is fired to take off, I’m super ready to go and there’s plenty of stuff. Having taken the time to think ahead and develop my ideas, I have a very clear perspective moving forward. Now it’s just a matter of coordinating logistics and really the biggest challenge is time. I’ve always been good at working every possible angle, exploring lots of different possibilities as far as work and life is concerned. It feels pretty normal to me.

My time is so insane now. It’s kind of incredible. Thank god I’m a New Yorker, and thank god I love endurance performance, because that is basically what I do all the time now—endurance performance.

Essential Casey Spooner:

-

“Emerge”

-

“Togetherness” featuring Caroline Polachek, produced by Michael Stipe