A harm-reduction guide to using your phone less

Prelude

Max Fowler is a freelance programmer and artist living in Berlin. He makes open-source software, interactive installations, and websites. His recent work involves blocking social media, printing it out, reading it out loud and imagining new ways that social networks could work. In the past he lived in New York, co-founded Computer Lab, and participated in the School For Poetic Computation.

Conversation

A harm-reduction guide to using your phone less

For TCI x Are.na's Library of Practical and Conceptual Resources, programmer and artist Max Fowler shares creative tactics for disconnecting.

As told to Max Fowler, 1857 words.

I have a fantasy where I’m standing on a cliff overlooking the ocean and with two hands I throw my laptop over the edge. The MacBook leaves my fingertips, and there is no turning back. It’s just me, a couple of friends, and the wind from here on out, and we sit in the grass and look out at the ocean. Never again will I click “remind me to update this software tomorrow.”

**

The above is a fantasy which I don’t plan on realizing for a variety of reasons, but in the absence of following through on it, I would at least like to look at my phone less. I have a lot of respect for hermitage, deleting your account, and moving to the woods, but ‘full isolation’ and ‘fully connected’ are not the only two options. Over the past few years I’ve experimented with a number of different techniques for partially disconnecting. With the hope that my learnings might be helpful to someone else, or that they might at least serve as a jumping-off point to try something new, what follows is a harm-reduction guide to using your phone less.

Freedom through constraint

It’s not that it’s impossible to not look at your phone when you’re thinking about it—it’s more that in the times we’re not thinking about it, our habits act as the auto-pilot.

Even when you’re not looking at your phone, the possibility of distraction can create a particular feeling (e.g. this study). People seek different environments for different activities (this is why libraries are so quiet), and if an internet-connected device is always in your pocket, it has an effect on every environment you experience. Is this really what we want?

When social media isn’t at my fingertips, at first I experience a bit of withdrawal. But then the world begins to feel more full to me.

I have a distinct memory from two years ago of eating lunch with a friend in a park in Chelsea, NY. As an experiment, I was using a flip phone for the week. It was pretty inconvenient, and only worked because at that time, my schedule didn’t require much on-the-go planning. But that day, sitting in the park with my friend eating lunch, I felt present in a way that stayed with me. There was so much space—as if it was just the two of us and there was nothing else.

Since then, I have experimented with a number of different ways of making disconnection part of my life, while not giving up on connectedness entirely.

I like being able to use Google Maps when I’m lost, and I learn a lot from the internet, but for me, having access to ‘all the applications all the time’ feels like a bad design. What’s more, an always-accessible device that fits in your pocket can build compulsive habits. More use is always better for the company selling you the product, but not always for you.

In the words of Tristan Harris, the founder of Time Well Spent, “You could say that it’s my responsibility [to exert self-control when it comes to digital usage], but that’s not acknowledging that there’s a thousand people on the other side of the screen whose job is to break down whatever responsibility I can maintain.”

Looking away from the screen opens up new space for thought. In this way, perhaps the reclaiming of your own attention from the companies trying to monetize it could be a radical act (or, at the very least, it could be a small thing that makes your life better).

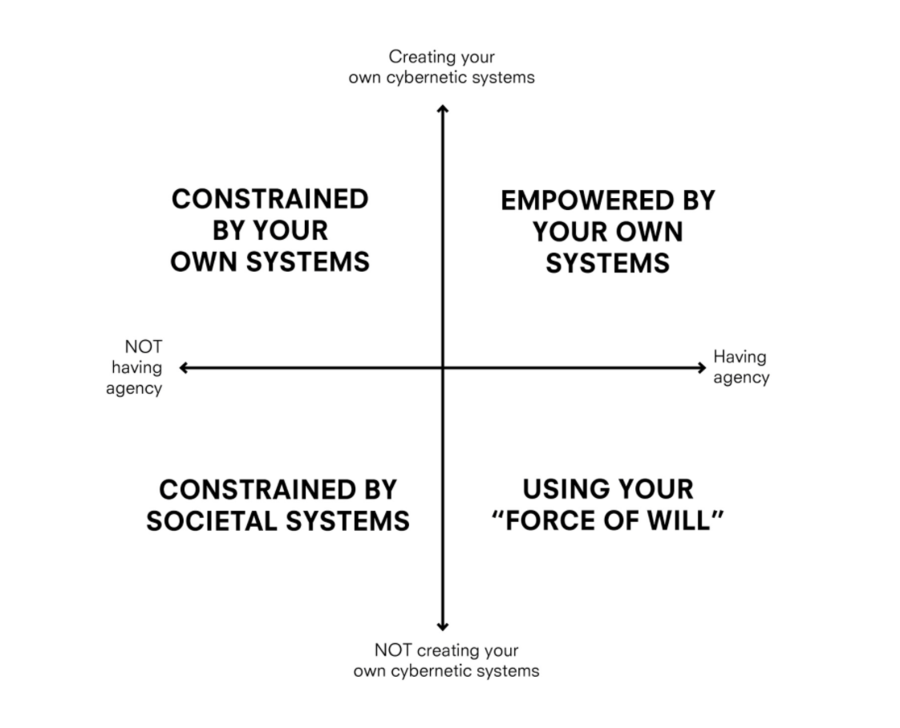

Dan Taeyoung and I created the below 2x2 as a framework for thinking about agency, systems, and freedom through constraint:

Using the above as a framework, what follows is a combination of tools and practices for finding disconnection. You can also ignore the theory, and just try things for yourself.

Tactic 1: Just not using your phone as much

With perfect mental discipline, perhaps we could just think, “I would like to look at my phone less,” and that would settle things. This may be possible for some people, but for me I’ve found it to be more complicated.

If you are someone who sometimes finds you have a negative relationship with your phone, or ever find yourself thinking, “Why am I scrolling through this feed right now,” other tactics in this guide might be more helpful.

Tactic 2: Buying a dumb phone

Two years ago I tried using a “dumb phone” (an AT&T flip phone) for one week. There were a lot of things I liked about it, but on-the-go planning and navigating was definitely harder, especially when everyone else expected that I’d be able to make plans through text message and find any address on the fly.

Depending on what’s happening in my life, I could see using the dumb phone again. Despite the inconveniences, my experience with the dumb phone inspired me to seek out more ways to find disconnection. It felt good to leave my iPhone at home in a way that I never felt just leaving the iPhone in my pocket.

Tactic 3: Pin friend (for iPhone)

This is my favorite method and the method of disconnection I currently use. The idea was born out of really enjoying using a dumb phone, but finding it difficult to navigate without Google Maps. I wondered, “Is there a way I could have a phone that just offered texting, phone calls, and maps?” It turns out, there is:

Using the iPhone Parental Restrictions feature you can set your phone so that you can’t install new applications and can’t use Safari. (Here’s how)

Before enabling the above restrictions, I install just the applications I want to be able to access all the time (for me this is Google Maps, Simplenote, Venmo, and Lyft). Then I ask a friend to child block my phone for me using a pin that I don’t know. Not having Safari is sometimes inconvenient, but I find most things really can wait until I am back at a computer, and to me this inconvenience is outweighed by how it makes me feel overall.

If I ever want to change my app settings, I can always text my friend and ask for the pin—but for me, I find this social layer makes a big difference. Having a friend in charge of the pin is somewhere between BDSM and making your intention concrete through spectacle, like with marriage.

Tactic 4: Freedom (for iPhone, Mac, or Windows)

Freedom is a paid service that allows you to block internet access to particular domains. This app also enables you to create different settings and schedules for your phone and your computer. The service uses a VPN and works well. I find it similar to child-blocking my phone (which is free), but it gives you more fine-tuned control over what you’re blocking. It would also be interesting to create a Freedom setting and then ask a friend to set a password you don’t know.

Tactic 5: Do Not Disturb (for iPhone, Android)

If you’re not putting your phone in Do Not Disturb (or Airplane Mode) before you go to sleep, you are committing self harm. Waking up from an Instagram notification is not worth it.

If you can, I would also recommend keeping your phone in Airplane Mode during your morning routine. Two years ago I made a commitment to that for one week, instead of checking Facebook as soon as I woke up, I would get out of bed and meditate for 10 minutes before looking at my phone. I found I really liked starting the day this way, and I have continued to do it ever since.

Tactic 6: Camping

This is not new, but sometimes it’s worth revisiting the obvious. If you have the privilege to be able to truly remove yourself from the grid, even for a short period of time, nature is really nice. It’s kind of like society, but better in most ways. You can set an auto-response saying when you’ll be back on the grid, and then leave your phone in your bag the whole time (unless you have some kind of emergency).

Tactic 7: Pasta box as Faraday Cage

I found that sometimes I enjoyed that there was no cell phone service in the New Museum’s basement. I dreamed of building my own Faraday cage.

To simulate a Faraday cage without totally encasing my apartment in steel, I put an empty pasta box on a table next to my front door. When I entered my apartment, I would put my phone in the box to create the sense that I was in a room without service. I imagine it would be nice if there were more spaces and rooms where leaving your phone outside was a suggestion similar to taking off your shoes.

More tactics: Honorable mentions

I won’t spend time explaining each of the disconnection techniques listed below, but they’re all worth a look:

- Light Phone — a minimal phone

- Lock Me Out — an Android app that lets you block apps for periods of time

- Kill News Feed — a Chrome extension that blocks the Facebook news feed

- Self Control — a Mac application that blocks domains for periods of times

- Redirector — a Chrome extension which you can use to literally redirect Facebook to another page (which is an apt metaphor for rewiring habits)

Tactic 3,247,284: Compassion

Like any self-help practice, there is the risk that suggesting a way to change could lead to judgment of the self or others.

Using your phone and not using your phone can both be good decisions, but I hope to encourage mindful consideration of when we are using our phones. And if you would like to try to use your phone less, I hope these ideas can help.

**

On June 4th, Apple announced a new set of features being released with iOS 12 to help reduce interruptions and manage the amount of time we spend with our phones. It sounds like the new features could pair nicely with the ideas in this essay, but it will be interesting to see how they are used. This guide is not an endpoint. Over time I hope to continually ask the question of when and how I need to be connected, and how I can find time away—whether that’s by taking out my neural implant or by putting my iPhone under water.

For the Library of Practical and Conceptual Resources, I’ve put together a collection of related tools and links. You can explore it here.

If you have other techniques you use or would like to share your experiences, please send me an email.

- Name

- Max Fowler

- Vocation

- Programmer, Artist

Some Things

Pagination