A soft manifesto

Prelude

Cortney Cassidy is an artist using text, image, performance, and sound to write poetry.

Conversation

A soft manifesto

Artist and writer Cortney Cassidy on the anti-capitalist values that helped her launch Mail Blog, and a set of principles you can apply to your own values-driven art making.

As told to Cortney Cassidy, 1959 words.

Tags: Culture, Art, Poetry, Activism, Focus, Independence, Inspiration.

What does it look like to not lose as an artist? Especially when “creativity under capitalism is not creative at all because it only produces more of the same,” as Oli Mould puts it in Against Creativity.

Like many others, I feel burned out because I lost to capitalism a long time ago. I lost before I existed; before my grandmothers were teenagers with their firstborns (my absentee parents), both still grieving the early losses of their fathers to war and illness. Capitalism is a cold indestructible mass that embraces no one. Even for the winners of capitalism, the only way to persist is to develop toxic politics and relationships.

The desperation, exhaustion, and hopelessness in both the content of my thoughts and the method of capturing my thoughts exist because I work to live without getting to actually live, or process living.

I have a series of little identical notebooks crammed with lost context like “coca-cola clown,” “claim his absence,” and “how to feel ~ or something.” These words sit between lists of unresolved work and post-therapy thoughts written without looking because I was lying awake in the dark or driving. As Deleuze and Guattari put it in What Is Philosophy, “Nothing is more distressing than a thought that escapes itself, than ideas that fly off, that disappear hardly formed, already eroded by forgetfulness or precipitated into others that we no longer master.”

Being an artist within an economic system that favors private property, capital accumulation, wage labor, a price system, and competitive markets belittles my practice into a hobby. I am an amateur with no artist statement, thesis show, or MFA. The money I invest in creating art is a temporary loan to myself that I feel pressured to repay quickly by attempting to exhibit wherever the crowds are.

The crowds are at art book fairs, the overwhelming substitute for gallery/curator representation that forces artists to act the part of an extroverted salesperson.

The crowds are following Instagram accounts posting new inventory daily to maintain engagement, captioned with personal-advertisement performances that drive customers to online shops.

Only some can make a living this way; others break even on costs or make enough to cover the flight. The majority don’t get into the fairs at all or attract enough followers.

When I aim for these crowds, the result is an unfortunate lack of creativity. I get trapped in a pattern of making “sellable” products in quantities to keep a table full, but I end up with a pile of dead stock every time.

This pattern doesn’t seem like an art practice. It is business performance, and I have no business expecting people to consume things they don’t need, or participating in the growth of capitalism, or adding to the floating debris in the ocean.

The entrepreneurship of mainstream do-it-yourself artist-as-business comes from a place of economic motivation, and rightly so under a system that requires money to survive. It perpetuates “more of the same” because there is no freedom to take risks. In contrast, the DIY spirit of alternative subcultures like vegan punk houses, feminist community centers, and peer-to-peer educational programs seek empowerment and community. It fosters healthy divergences to help us understand what we may not have understood before.

If you aren’t in the status quo, it takes a lot of miscalculated physical, mental, and emotional energy to force the fit. To keep up with the pace of fitting, it takes a passionate working style, glorified as hustling (which was recognized as an early sign of an impending nervous collapse, way back in 1909).

As a hard worker who is often pushed to the limits, and who spends much of my free time on “side projects,” I have taken several unpaid breaks that I couldn’t afford, just to rest. Productivity addiction, like other types of addictions, is a coping mechanism. It’s a habit formed to ward off emotional distress that gets louder when the mind gets quieter; a habit that can go on for a while before realizing you are actually suffering. But eventually, working hard on terms that don’t feel naturally good leaves little space for reflection, and no time to refocus.

How can I contribute well as an artist if I don’t think about my principles?

An entry in an old journal reads: “I need to wake up earlier and take care of my body and take care of my brain that holds on to all of my ideas, a backlog that will just fade into the dark.” I answered this concern by making a list of those ideas floating in my head at the time. Reading them now, they did not age well, but what bothers me more is I never found the time to get around to any of them.

I have post-rationalized a lot of my work because I didn’t have time to plan what I was doing. I was reacting to a compulsion to create and stay busy. While there is value in the unplanned results of creative output, there is more long-term value in knowing what you want to say and figuring out the most effective way to say it.

It’s not easy to find extra time and energy to exist when the part of you that learned how to assimilate by being productive is stronger than your “real” self.

Mainstream society is uncomfortable when someone isn’t trying to harness and monetize a boundless ambiguity. Like the “what for?” and “but why?” I get at my corporate job when I experiment on extracurricular projects like recruiting some of my coworkers to make a short film about everyday color theory. To ease their discomfort, I answer in terms that present some potential (if unconventional) viability.

The monetary motivations of capitalism can be a comfortable place to some because it is known. Capitalism is a well-established masculine monoculture of stoicism, competitiveness, dominance, and aggression that relies on dependencies and power structures. I lose my autonomy in it as a sensitive introvert. If I could exist in an undefined space instead, I could use the ambiguity to nourish my emotional needs and create soft definitions of what it means to be.

The power structures of capitalism define who is publishable and who isn’t. Several years ago, I wrote a poem composed of phrases from rejection emails I received after submitting poems to various publications. I called it “I’m Just Going to Keep Doing This Until I Die” and intended to send it to the same publications. The idea wasn’t very radical. I realized there was no need to make some loose, self-centered point to the overwhelmed editors. They already have “poems titled RAIN [pouring] in from across the nation,” as Sylvia Plath reminded herself in her journal when she felt tempted to write a poem during a storm.

Self-publishing breaks down barriers between an artist and an audience. It lets the artist define what is publishable or not. I decided to publish the rejection poem myself on my own internet: the email inboxes of my friends. I called it Email Blog.

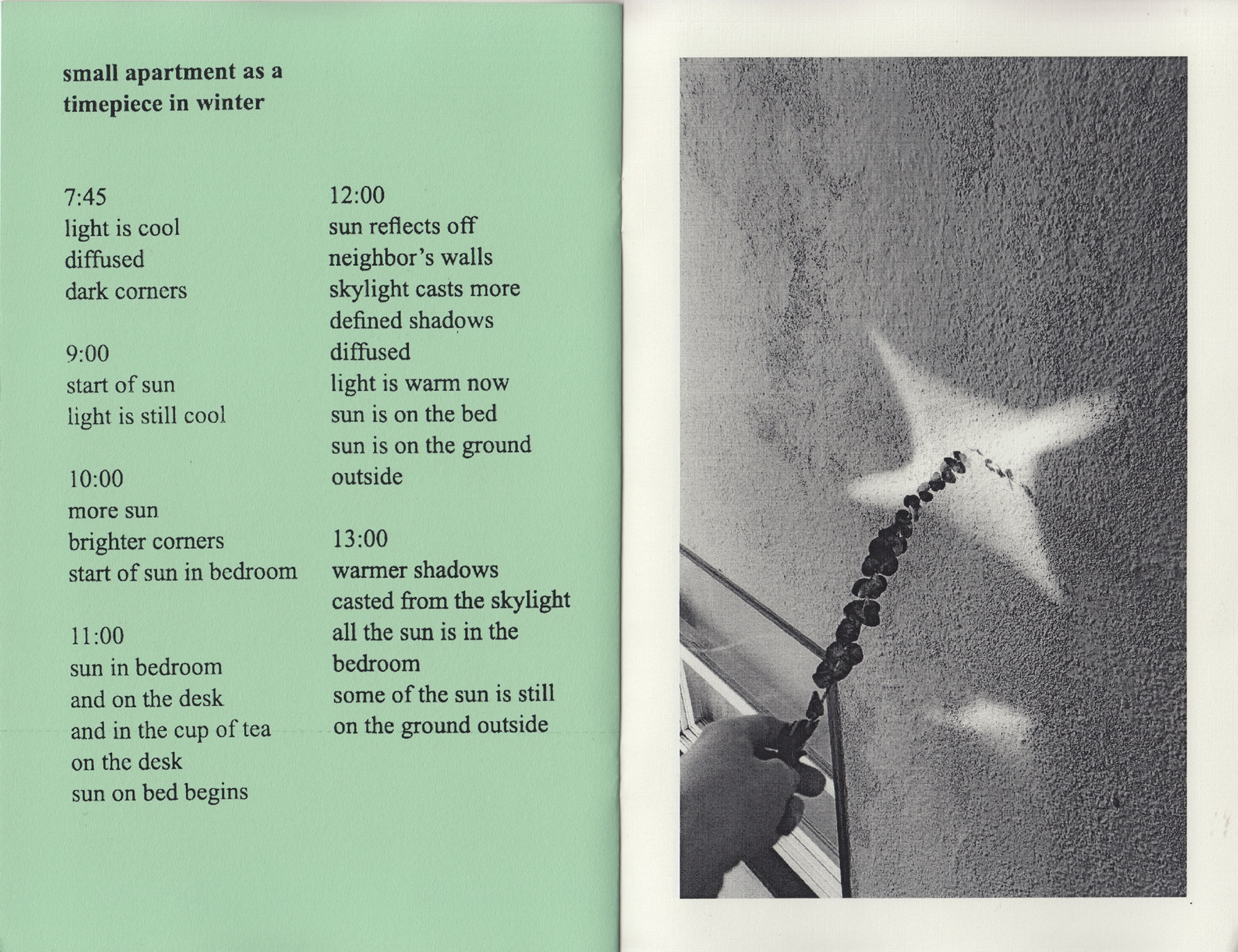

Email Blog became my monthly newsletter where I explored topics that caught my attention, like the discomfort of boredom or the comfort of rain sounds, and connected them with personal anecdotes. I ended each email with underlines from whatever I was currently reading and one of my unpublished poems. To avoid making it all about me, I offered custom poems based on subscriber-submitted words and created public Google Docs with abstract doodles to crowd-source interpretations.

Email Blog cleared my backlog of unpublished works that silently prevented me from moving forward. After a couple of years, I opened up enough space to see the act of contributing to the stressful inbox load of others was counterintuitive to how I wanted to contribute. Forcing my voice to fit in with marketing emails and Amazon order confirmations was a quick way to lose my voice.

Voice isn’t only about what you sound like and what you say; it’s also about how you deliver it. As Rebecca Solnit describes it, a writer’s voice is “something of the personality and the principles of the writer, where your humor and seriousness are located, what you believe in, why you write, who and what you write about, and who you write for.”

Needing to take my voice offline, I decided to extend Email Blog into its current form: Mail Blog. Through it, I encourage an exchange of physical trades and letters instead of emails. In its easy-to-mail, simple zine format, my voice, and the eyes of anyone who reads it, can be free of the screen, and harder to lose.

I fund Mail Blog by siphoning money from the man (i.e. the paycheck I get from my corporate job). I redistribute it into the communication commons in a format that costs me one Forever stamp to send, and source supplies from creative reuse shops when possible to keep it affordable. By giving work away for free, my expectations, and the expectations of the readers, can stay soft. It is a fresh start for me to expand and build my definition of what it means to be an artist and where I can be an artist.

When you’re losing a game you don’t even want to play, or forcing a fit into a form you don’t want to be in, the best thing to do is to stop playing and go find your shape. “If we accept ourselves and each other as form-makers,” wrote American philosopher Eugene Gendlin, “we will no longer need to force forms on ourselves or each other.” Through forming my framework to create in, the return investment is not a monetary profit. The gain is my revolutionized vocabulary of art in a softer space. Like Linda Montano, who used her performance art to practice for life, I can “free myself from everyone else’s definition of art.”

In taking on at least one project to actively apply my principles, I can make them stronger, like a low-impact workout that’s gentle on the knees. The refuge I’ve found in Mail Blog allows me to be more deliberate with my time in a fragile ecosystem that could collapse with one unfocused decision. To protect this space, I check myself against a set of principles as I work. Adapting the idea of rules, like Sister Corita Kent’s Ten Rules for Students, Teachers, and Life or Bertrand Russell’s Ten Commandments for critical thinking, which can be broken if not followed, I form my own as questions I can answer with actions and decisions.

These principles act as a soft manifesto for myself, and for anyone else who wants to be an artist practicing for softer reasons at softer paces in softer spaces:

- Can you afford to break down any barriers between your work and the audience? (monetary, language, accessibility, etc.)

- What can you gain, that is not money, from the work?

- Who, that is not you, can gain from the work?

- Can you remove yourself from the center of the work?

- Does the work consider its impact on our planet?

- Does the work consider your politics?

- Does the work reflect your understanding of the responsibility of being human?

- Have you learned all you can from the work before presenting it as finished?

- In what ways have you grown or changed from older work, and are you proud of these changes?

- Can you afford to rest?

- Name

- Cortney Cassidy

- Vocation

- Artist and poet

Some Things

Pagination