On the peaks and pitfalls of being a songwriter in a band

Prelude

Miki Berenyi is an English singer, songwriter, and guitarist best known as a member of the alternative rock band Lush. After the band’s breakup in 1996, Berenyi stepped away from music for several years, working as a copy editor. After a brief reunion with Lush in 2015, Berenyi would later go on to play in Piroshka, a band she formed with former members of fellow British bands Modern English, Elastica, and Moose. Piroshka released their debut album, Brickbat, in 2019.

Conversation

On the peaks and pitfalls of being a songwriter in a band

Musician Miki Berenyi on the creative energies that bring bands together and pull them apart, the value of stepping away from your creative work, and reconnecting with the pleasures of simply making music with your friends.

As told to Miki Berenyi, 2955 words.

Tags: Music, Process, Beginnings, Adversity, Success, Money, Failure, Mental health.

I was 18 when I bought my first guitar—a cheap Fender tele—but I didn’t have much patience for practicing and I never got around to writing any songs. I just wanted to be in a band–not so much driven by a need to express, as a desire to be involved. As Emma Anderson and I sat in her sub-zero flatshare, me haltingly changing chords while Emma plugged her bass into the stereo and we attempted a cover of The Delta 5’s “Mind Your Own Business,” it became evident that our sketchy musical abilities were not going to facilitate any kind of spontaneous jam session. Instead, we would need to go away and separately work on songs in such a way that we would know our parts before we made any attempt to physically play them together.

By the time we became Lush in 1987, with Chris Acland, Steve Rippon, and Meriel Barham on board, songs were brought to the band almost fully written. There was some experimentation at the rehearsal stage—Chris had the most leeway with the drums, effects pedals would be deployed, occasional backing vocals were introduced, and arrangements might be tweaked—but “Sunbathing” was Emma’s song, “Bitter” was Miki’s song, and “Skin” was Meriel’s song.

This method worked well for Emma. She had a flair for experimenting with made-up chords and unusual combinations of bass and harmony, and preferred to do this alone and without interference. I could happily launch myself from one starting idea—an interesting drum break, a bassline hook, a descending vocal that sounded nice over an E minor chord—but would often run out of steam by the time it came to composing a second guitar part or anything resembling a middle 8. I loved writing lyrics for Emma’s songs–I was much happier with “Etheriel” and “Scarlet” than anything else I came up with on our 1989 debut, Scar—because I could get lost in writing and rewriting lyrics, experimenting with rhymes and vowel sounds, and tweaking the slip and slide of meaning, whereas repeatedly trying to nail down the finishing touches to my own songs was frustrating because I didn’t have the ability or the patience to fix the parts that fell flat. I recall Ivo Watts Russell (4AD chief) saying to me of “Second Sight” that he could see what I was trying to do but… it just wasn’t quite working. Totally.

Signing to 4AD got us some advance money to buy music-making tools. My songwriting relies on trial and error, and I benefited from the little 4-track Portastudio that let me fit the parts together to hear them in unison, and programming a drum machine to add dynamics to flesh out the song. It was still time-consuming and laborious—suddenly deciding to insert a second chorus meant re-recording the whole song because I wasn’t about to start scissoring fragments of easily tangled tape from flimsy SA45 cassettes. But by the time we recorded Spooky in 1992, I had improved, and having “For Love” released as a single boosted my confidence significantly.

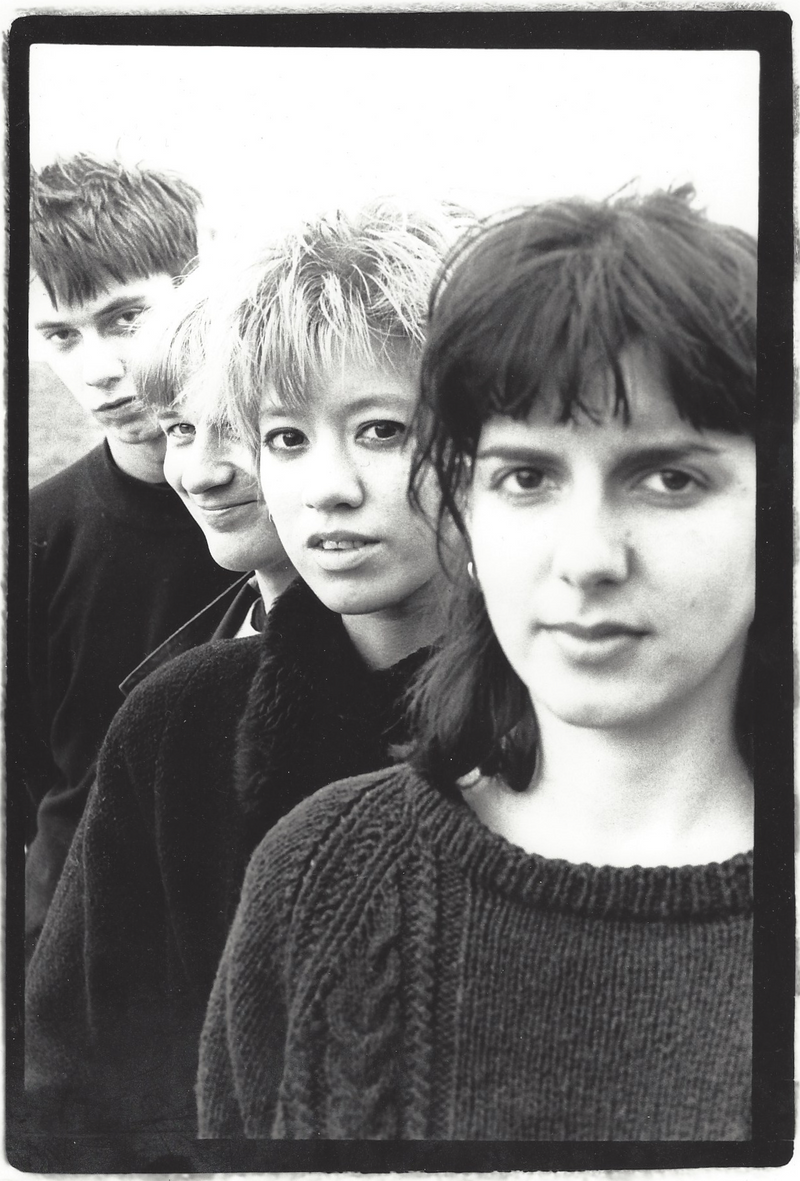

Lush, the early days. Credit: Renaud Monfourny

For all the critical cooling on 1994’s Split, I think it contained some of our best songs. “Light From a Dead Star” is still my favorite self-penned Lush lyric—my childhood sadness neatly tied up in three verses. I was mining my feelings and memories to create stories I hoped were moving and true, but also to make sense of who I was, which felt cathartic. However, if you’re going to expose your wounds to the world, you have to be prepared to withstand the scrutiny. One critic’s withering dismissal was that Lush only sang about fluffy clouds; another yawningly commented (regarding “Kiss Chase”) that there was nothing new here: “Everybody already knows Miki from Lush was abused as a child.”

I’d been bruised by the dismissive reviews for Split, and wasn’t resilient enough to repeat the ordeal of having my lived experiences belittled and ridiculed—so our lyrics for 1996’s Lovelife were less to do with delving into inner damage and more about flinging back any upset at the perpetrators. I didn’t abandon personal lyrics altogether, but they were more confrontational, like I was ready to attack back.

It’s worth pointing out at this juncture that despite our outwardly successful collaboration, Emma and I did not have an easy relationship. Anyone who has known the two of us well—friends, boyfriends, band members, touring crew, record-label bods—will look skyward, puff out their cheeks and let out an explosive don’t-even-go-there sigh when asked, “What the fuck is going on with those two?” I can’t provide a simple answer. We could and did get on, but we never quite trusted one another.

A bit of competition and conflict can be a driver, and I would never have put in the effort to become a better songwriter if I hadn’t had Emma setting the bar so high. But, it also created a lot of unnecessary stress and wasted energy. By the time we reached the final months of an exhausting year of touring, Emma called a band meeting to announce that she had had enough. I’d guessed as much from her recent behavior toward me, and we tried to broker a path to giving Lush one last go–my feeling was that we were stronger together than apart, so we should do whatever it takes. But a week later, Chris committed suicide.

Is it weird to get to the age of (almost) 30 without having experienced the death of someone you love? I was utterly unprepared, in every way. Not just the shock at the brutality of what Chris had done, and my regret and self-blame of not recognizing the signs, but the finality of this loss—I couldn’t accept that he was gone forever. I would hear the latch of the front door and immediately think, “Oh, that’ll be Chris”–and expect to see him appear, wheeling his bike through my flat to the back garden. Or I’d spot someone in Sainsbury’s who looked just like him from the back and go chasing after them, frantically negotiating the aisles to definitely confirm that it wasn’t him. I would wake from vivid dreams where Chris was alive and it would take me several minutes to remember that he wasn’t.

Throughout this, my partner Moose was a rock and a comfort (our relationship started earlier that year), as were so many friends. We talked and reminisced, and explored how and why any of this could have happened. But I stopped going to gigs and listening to music–it felt joyless and lacking without Chris–and immersed myself in mine and Moose’s relationship, our home, and a close circle of friends.

It was Chris’s aunt Sue–who worked at Harper Collins–who suggested I get into sub-editing. I did an online proofreading course, and she hooked me up with her friend Mitzi Bales, a sharp-minded indefatigable American woman in her seventies–feminist, anti-war, active in the National Union of Journalists. She had been mowed down on a zebra crossing by a hit-and-run driver, so was having to work from home while on the mend. I would turn up with any groceries she needed, and gifts of cake and bread from Bonne Bouche, and she would mentor me and supervise my work, and recommend me for jobs.

Eventually, via another friend—Liz—I ended up working at IPC, for their TV mags. It was the same company that published NME and Melody Maker, and colleagues would often ask why I didn’t work for the music weeklies, in a field I had close knowledge of, but by then my cut-off from my old life was thorough and deliberate. I made a couple of forays–wrote the theme music to a TV show, provided vocals and lyrics on a couple of projects–but nothing long-term grabbed me. I felt lucky to have found a new career, where I had the stability to pay my mortgage and raise my children. Anything music-related would have been less-than-Lush, so what was the point?

Added to this was the feeling that I had been left behind. Chris was dead, Emma had formed Sing Sing, Phil had joined the Jesus and Mary Chain. And while I’d had a wonderful time in Lush and treasured my memories and the band’s achievements, the incessant sneering from an increasingly tabloid music press had worn me down, while the rise of Britpop had cast us aside as also-rans, left in the dust by younger, newer bands who were far exceeding our successes.

And yet, as the years passed, Emma and Phil–both keenly engaged in social media (I had steered well clear)–assured me that interest in Lush was alive and inspiring a new generation of shoegaze bands. In 2010, Graham Bendel wrote a piece for the Quietus marking 20 years since the release of Spooky where he quoted praise from Greil Marcus to Parry Farrell, and compared us favorably to My Bloody Valentine.

Apparently, there was still some love out there for Lush, and when the reunion finally took shape in 2016 (with Elastica’s Justin Welch stepping in on drums), Emma had some songs that she was ready to develop with producers Daniel Hunt and Jim Abbiss. My part was to come up with the lyrics, but I hadn’t written a song in over 20 years, and I struggled to remember how I’d even begun to translate thoughts and feelings into rhyming lines.

Looking back at our earlier work for inspiration and guidance, it was the contemplative mood of Split that resonated more for me than the confrontational tone of Lovelife, and my lyrics for Blind Spot were inspired mainly by the way in which some memories become significant as you grow old—first love (“Burnham Beeches”), lost friends (“Lost Boy”)–and the overwhelming emotions of being a parent (“Out of Control”, “Rosebud”).

I have fond memories of recording Blind Spot in 2015. I’d been worried about how Emma and I would get on being in band together again. The past rifts were still vivid for me, and now here we were again. But she enjoyed having me there for the recording and the mixing, and valued my input and opinion, even though they were her songs. It was exciting and rewarding—and a lot of fun—to be back in the studio, being a part of making a record.

For Phil, however, the reunion was more precarious. I had always assumed that he loved touring and being in a band so much that the unequal roles didn’t bother him. Of the three of us, it was Phil who had continued to perform throughout the years, and he’d seemed mostly happy to stick with the Jesus and Mary Chain for a decade or more in a secondary role to the Reid brothers. But I underestimated the unresolved objections that he, too, had from the past.

It feels shabby to bring up money when you’re talking about art. But if money doesn’t matter, then why not pay everyone the same? Before we signed our publishing deal way back in 1990, I’d assumed we’d be splitting the money equally between the four of us, but Emma insisted that as the band’s songwriters, this was our money–mine and hers–because publishing is exclusively for songwriting. And given the way that we wrote, separately rather than collaboratively, I could see her point.

We didn’t keep it all to ourselves. Chris and Steve (and later, Phil) each got about half of what we got from the advance, but I still remember the fleeting shock on Chris’s face—quickly gone and replaced with an enthusiastic “Yeah, no, that’s great”—when I had to explain the deal to him. In the latter years of the band, Phil would faux-casually remind us that “Pulp split everything equally”—a mantra that he revived 20 years later throughout the brief Lush reunion.

It’s a tricky one. Emma and I put a huge amount of work into those songs, both in the effort of writing and time in the studio–and she had the most at stake because she wrote the most (and best) of them. But it’s not just about the advance. Every radio play, TV broadcast, and public performance generates exclusive financial reward for the credited songwriter. Unless you’re making a whacking profit from record sales and shows (we weren’t), it can be galling to realize that you’re touring for the better part of a year for a cursory daily income, while the very songs you’re working tirelessly to promote are generating a tidy sum for just one or two other members of the band. It’s also far easier to collectively pick which tracks will become singles or go on an album when you all stand to gain equally from the spoils.

Given the gripes I have heard over the years from bands that do divvy everything up equally, how some members feel lumbered with a disproportionate burden while others are accused of doing little to earn their share, I’m going to assume that this arrangement doesn’t eradicate all conflict.

Lush’s age-old problems were certainly constantly hovering in the wings. In discussing plans for future recordings, Emma would remind me that it’s not a Lush album without my songs, too. It was meant positively, and encouragingly, but the prospect of having to write with no collaboration (Emma’s songs, my songs—separate) daunted me, and I was fearful of a return to past conflicts over whose songs were prioritized. Meanwhile, perhaps because of his lesser financial stake in the record, Phil barely bothered to contribute to Blind Spot. His main income would come from the gigs, but even there I found him frustratingly lax; and then my failure to make it into the US over a delayed visa (they blame me, I blame me too but with a hefty load on the management), which cost us half our Coachella fee, disproportionately affected him.

Tensions exacerbated by stress (and alcohol) escalated into rows and finger-pointing, and after we returned from the US tour, Phil refused to play the remaining scheduled dates. We cancelled two festivals, and Mick Conroy (Modern English) stepped in to play our final show in Manchester–there was just enough time for him to learn the 23 songs required for the gig. Justin–bless him–made one last attempt to get Emma and I to bury the hatchet and overcome our differences–indeed, several other people expressed exasperation at the huge opportunity we were throwing away. For me, the only way forward would have been in fixing mine and Emma’s relationship; for Emma, I think the workload and stress of continuing with Lush far outweighed any benefits.

But there had been positives–I loved making the record, and the gigs had been far beyond my expectations. Even rehearsing–playing music and hearing the songs gel and improve, honing your craft and experimenting with different nuances in a performance–it’s a joy! So when Justin suggested that it would be worth writing some music together, I thought–why not? Mick and Moose were immediately on board and music files zipped back and forth across the ether, each of us adding elements and fleshing out the songs, eventually rendezvousing for rehearsals and recordings.

Piroshka, 2019

We had no plans for where this new project, Piroshka, would take us, and only discussed the band between ourselves and a handful of need-to-know friends. I felt like we were nurturing a fragile seedling, and didn’t want it overwatered by hyped-up expectations or trampled by dismissive criticisms. At least not until–if ever–we were up and running. It’s probably why I kicked against the “supergroup” tag, however enthusiastically meant–we weren’t doing this to hang on to the limelight of any Lush/Elastica/Modern English/Moose past, we were just four friends who were excited to have been thrown together and given the opportunity to create some music. And that’s pretty much how we’ve continued–recording an album, releasing it on Bella Union, touring in the UK and Europe. Each step celebrated and savored.

Still–Piroshka is no hippie elysium where we are all blissed out and threading daisies into each others’ hair. Giving equal voice to everyone, and having no overall leader, requires tireless discussion and compromise. But not to the degree that you water down every strong idea. Meanwhile, running a band is a ton of work and coordinating everyone’s schedules can be exhausting–it’s a fine balance, seizing the opportunities that come your way without becoming slaves to a treadmill.

In the end, I have no grand takeaways from my time in Lush. Piroshka is a new band, with different personalities, and it will face a whole other set of challenges. I’m no longer willing to chase success or acclaim at the sacrifice of personal relationships and physical and mental wellbeing–mine or anyone else’s—and I’ll never again tolerate making music in a hostile blame-game environment or participate in competitive victimhood–however brilliant the resulting records or gigs. Moose and I are a couple, with children, and our relationship has to withstand the pressures of working together. But just as important–I’m no longer willing to watch my friendships get destroyed by the pressures of a band. I no longer have any contact with Emma and Phil, and maybe that was inevitable—I can sit here and lick my wounds, justify it all and convince myself that I’m better off without them. But whatever ugliness we ended up hurling at each other, it’s a crying shame that the memories of our shared history are weakened and poisoned for the loss. There’s no way I’m going to let that happen again.

- Name

- Miki Berenyi

- Vocation

- Musician

Some Things

Pagination