On the power of mutual aid publishing during crisis

Prelude

Paul Soulellis is an artist and educator based in Providence, RI. His practice includes teaching, writing, and experimental publishing, with a focus on queer methodologies and network culture. He is currently Assistant Professor of Graphic Design at the Rhode Island School of Design, and Founder/Director of Queer.Archive.Work, a non-profit community reading room, publishing studio, and project space. Paul writes and speaks about art, design, and experimental publishing internationally, was a Design Insights speaker at the Walker Art Center in 2018, and was a featured speaker at the Eyeo Festival in 2019. Paul is also the founder of Library of the Printed Web, a physical archive devoted to web-to-print artists’ books, zines, and printout matter, now housed at MoMA Library in NYC.

Conversation

On the power of mutual aid publishing during crisis

Artist and educator Paul Soulellis on creating urgent artifacts, radical DIY publishing, and a call to document this moment.

As told to Paul Soulellis, 3052 words.

Tags: Art, Culture, Curation, Politics, Writing, Politics, Independence, Mentorship, Inspiration.

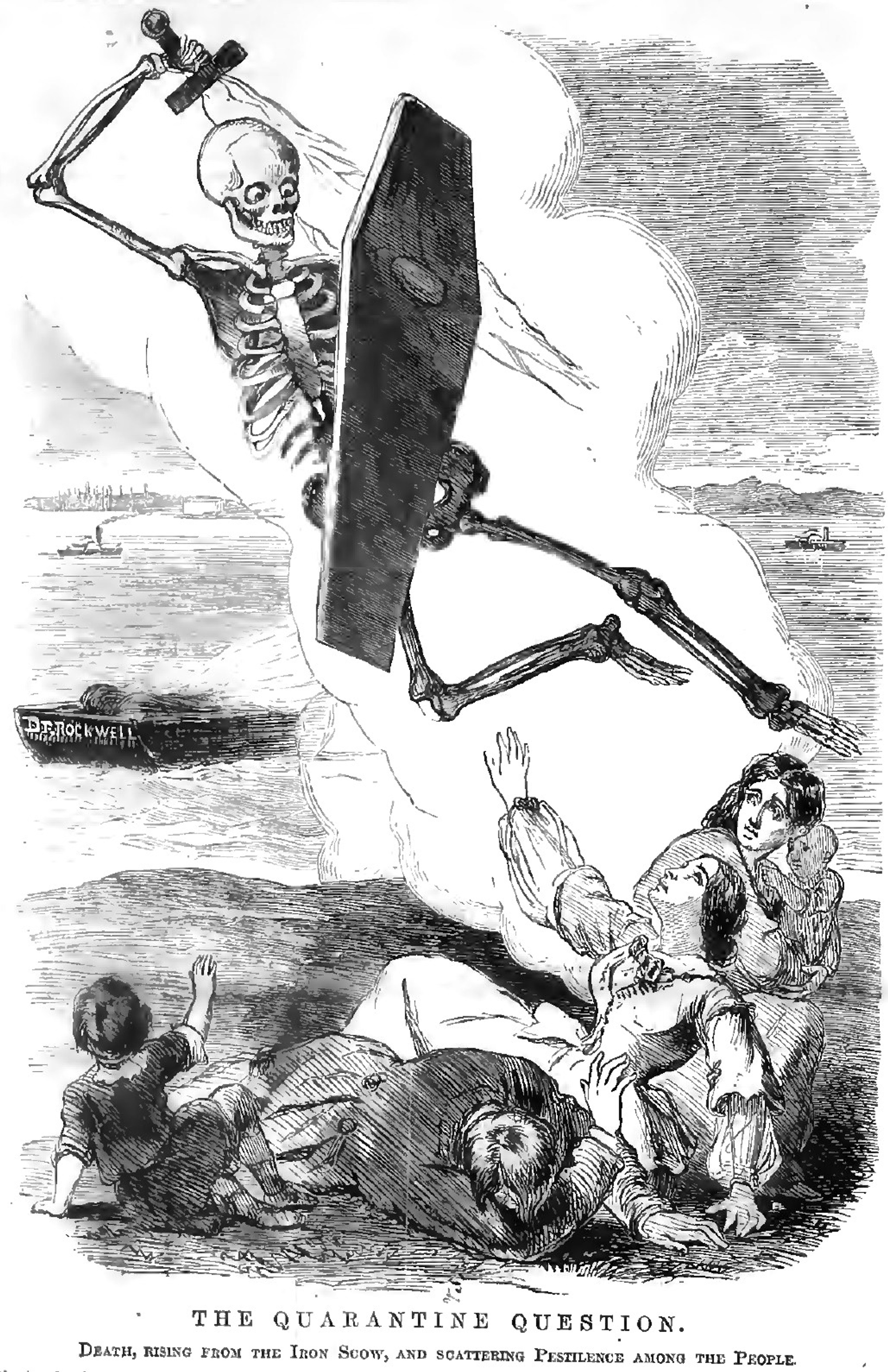

It’s mid-May and I’m about 58 days into my quarantine. The word “quarantine” comes from quarantena, in old Venetian, meaning 40 days, which was how long ships were required to be isolated before passengers and crew could go ashore during the bubonic plague. And although we’ve been contained, there’s something about this initial period of our own collective quarantena, those first 40 days in March and April, that for me was as much about mobilization as it was restriction. In that moment of slowing down, when 40 days felt like a year, we learned so much about how artists and designers can organize in crisis, through call and response. So what I’m writing about here is a contradiction, of sorts: how to get to work—urgently—during a shutdown.

Commoning-in-the-crisis

In crisis, we must organize. As businesses and schools closed in early spring 2020, and we started isolating ourselves and retreating to the screen, we saw a dazzling amount of mutual aid efforts beginning to circulate. It seemed like they appeared overnight, but they were built onto networks that had been fortified over time, way before COVID-19. Like many of us, what I felt most was fear, but also, below the fear, motivation. It was time to get to work, directing energy towards those who already and always carry the largest burdens, in our own communities and beyond.

What does communal care look like in a moment of crisis? Solidarity, mobilizing networks of people within and across communities, connecting needs with resources, and the redistribution of assets—these are some of the inspiring mutual aid strategies we saw in action during the first few days of the pandemic.

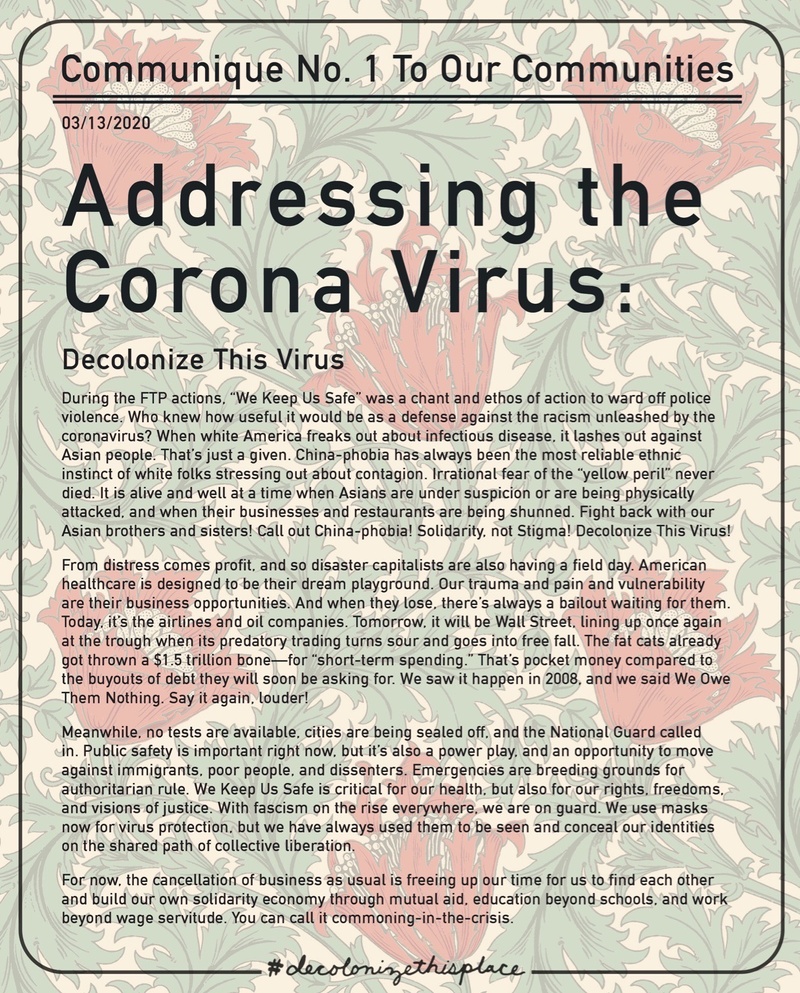

In this declaration on March 13, the activist group Decolonize This Place wrote that the shutdown is “freeing up our time to find each other and build our own solidarity economy through mutual aid, education beyond schools, and work beyond wage servitude. You can call it ‘commoning-in-the-crisis.’” We need to remember this phrase, because it foregrounds something very specific about solidarity and coming together in urgent times: that we can work from shared, common positions, in common, and on common ground.

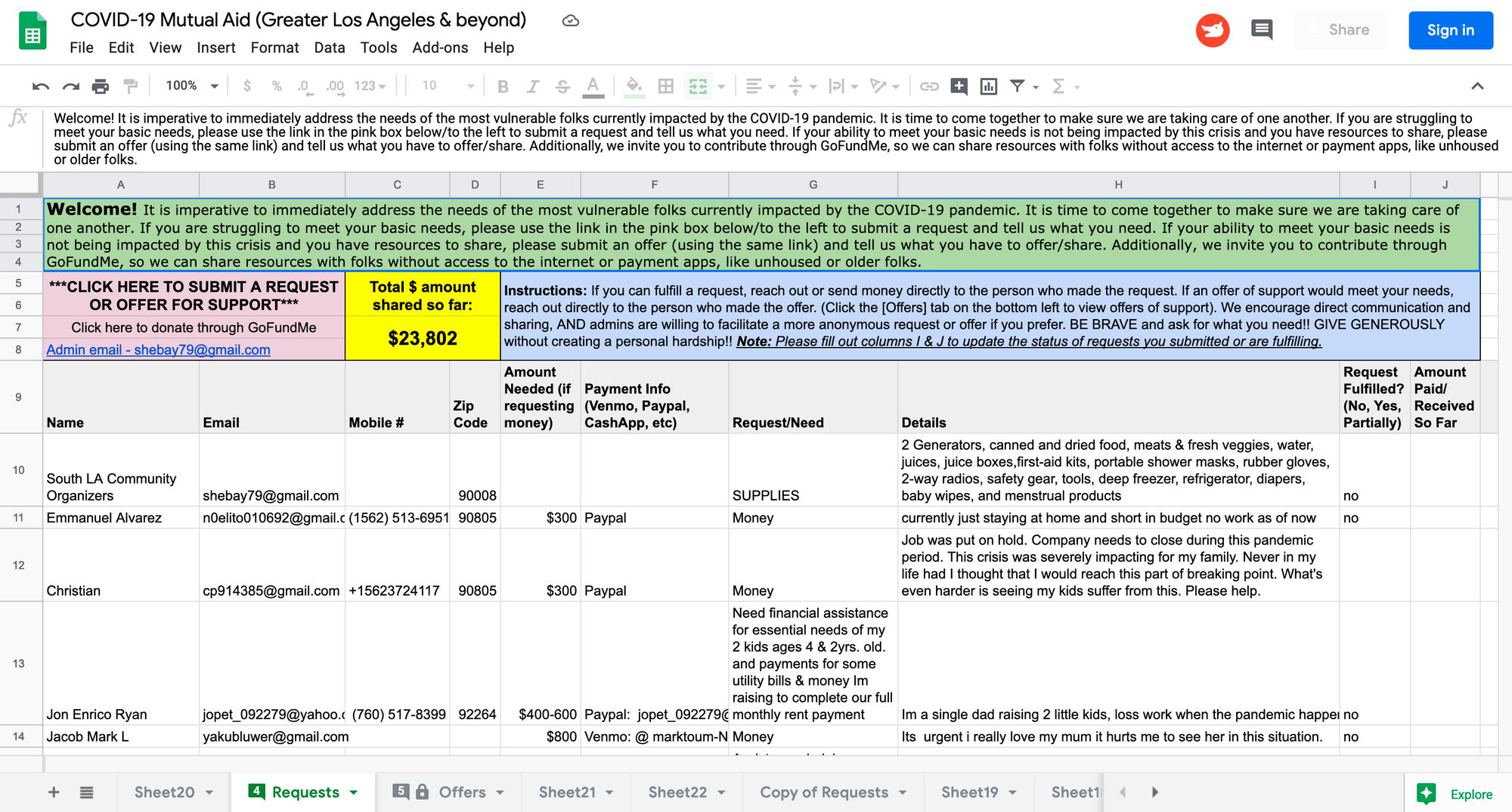

COVID-19 Mutual Aid - Greater Los Angeles and beyond, Google Doc, March 2020

Communal care

In the first days of quarantine, specific questions related to my own creative community came to mind, like: how can we provide relief to artists and writers being impacted by the crisis, in both creative and monetary forms? How should we collectively record and affirm the extraordinary conditions, language, emotions, and experiences before they evaporate? And how could my own practice learn from commoning-in-crisis, and adapt to become a better model of communal care?

No crisis is ever new. Depending on who you are and your specific relationship to burden and privilege, crisis can be a constant. BIPOC, queer, trans, disabled, femme, low-income, immigrants, survivors, and all other underserved and minoritized people have always known struggle. But our experiences are typically less visible, deliberately left out of archives, and erased from history.

Centering, amplifying, and preserving perspectives that exist outside of conventional narratives is essential first-aid work, especially during heightened times of crisis.

Let’s look towards those who identify, describe, and interpret what’s happening around them from less privileged positions; those who give us insight into the ways power operates, how culture shifts, and how justice can be served.

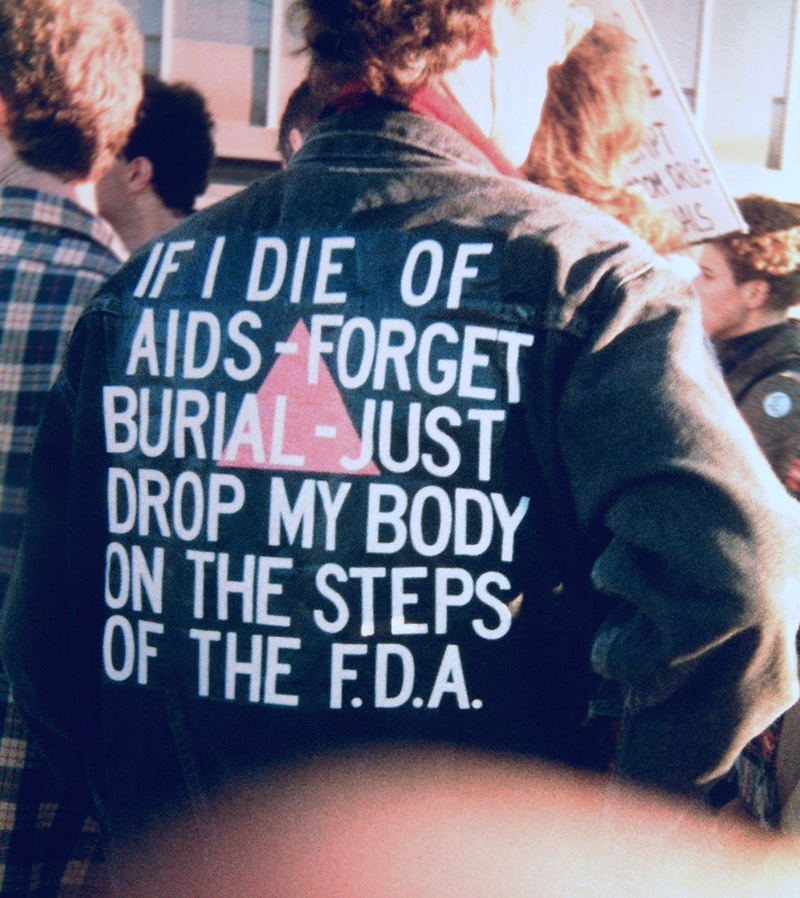

David Wojnarowicz, 1988

I think about David Wojnarowicz’s jacket here, worn by him at an AIDS demonstration 32 years ago. I see it first as an act of protest, but then as a gesture of publishing, manifesting an urgent message in public space, using the very body that is the subject of that message, the body that will die of the disease, as the platform for its dissemination. This jacket is so many things. It’s art, it’s graphic design, it’s a plea, it’s a protest at a very particular moment. It’s an urgent artifact.

Urgent artifacts

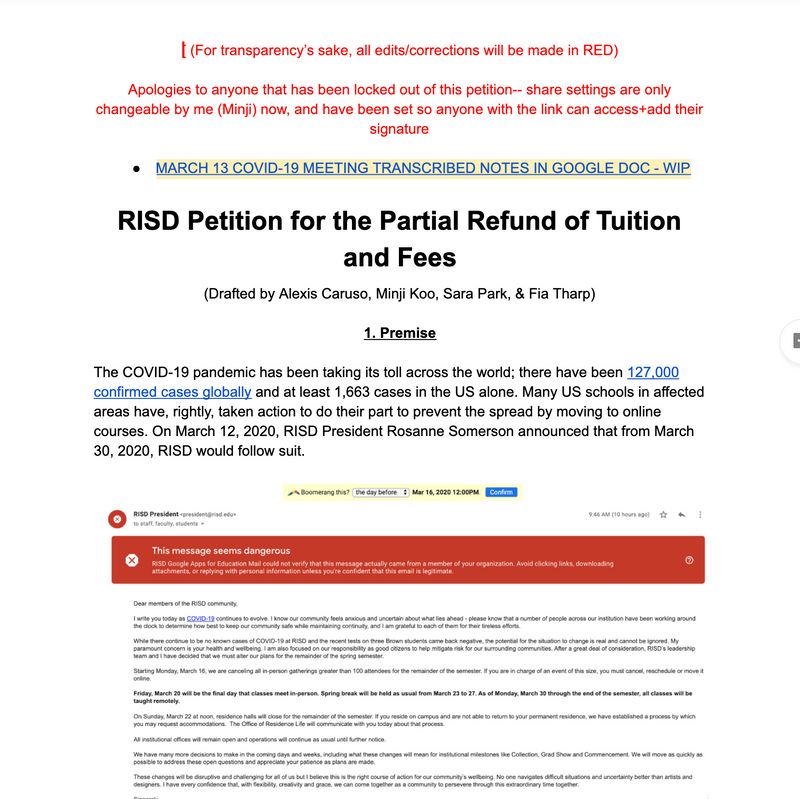

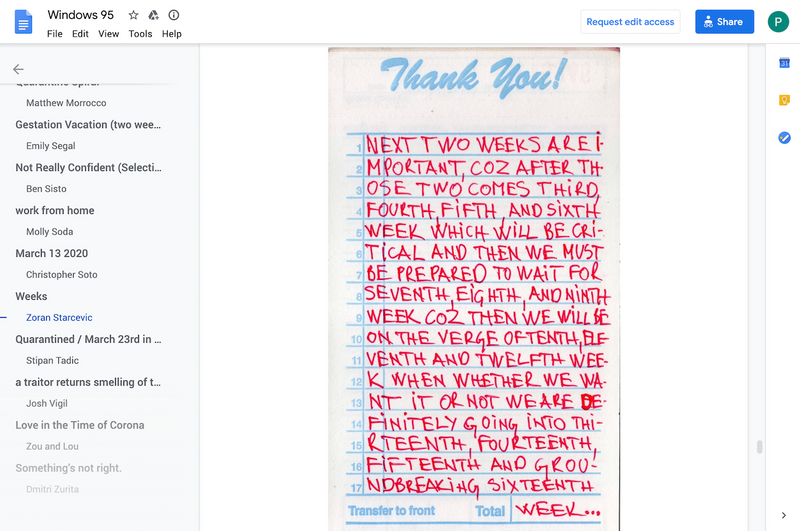

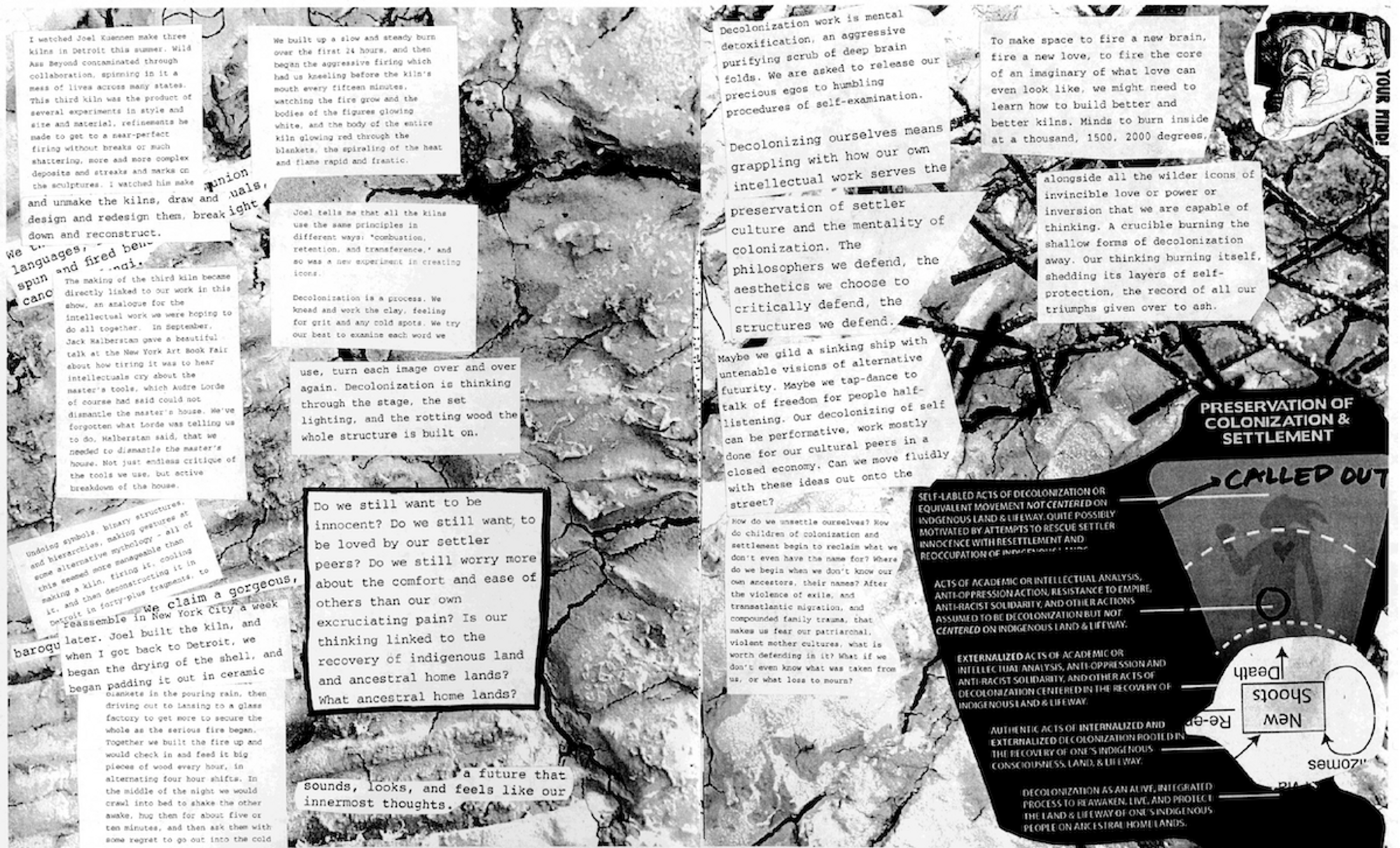

I saw so many urgent artifacts circulating during those first few weeks of quarantine, documents and projects and actions that don’t conform to what we normally think of as good art or design: collaborative google sheets, online petitions, protests, surveys, letter-writing, essay writing, note-taking, shared open-access writing spaces, streaming workshops, performances, talks, teach-ins, raw and unedited poetry, and quickly made zines.

All of these “urgent artifacts” were evidence of how a crisis spreads its toll unevenly in real time, with first-hand experiences shared and recorded in the quickest way possible.

Urgent artifacts expose our collective pain points and provide a fleeting record of the moment. It’s crucial that we acknowledge and make space for this work by affirming and supporting each other in non-traditional forms of making and creating, and preserve these urgent artifacts before they evaporate, for whatever comes next.

Studying stories of queer failure, and those voices that resist proper inclusion in the smooth narratives of history—and connecting them to our present condition—has been a valuable way for me to approach being an artist, and to teach design. And I see others doing it too. As our platforms and institutions fail us again and again, we need to look for new ways to tell stories, write histories, and complicate what we typically accept as good or new or important.

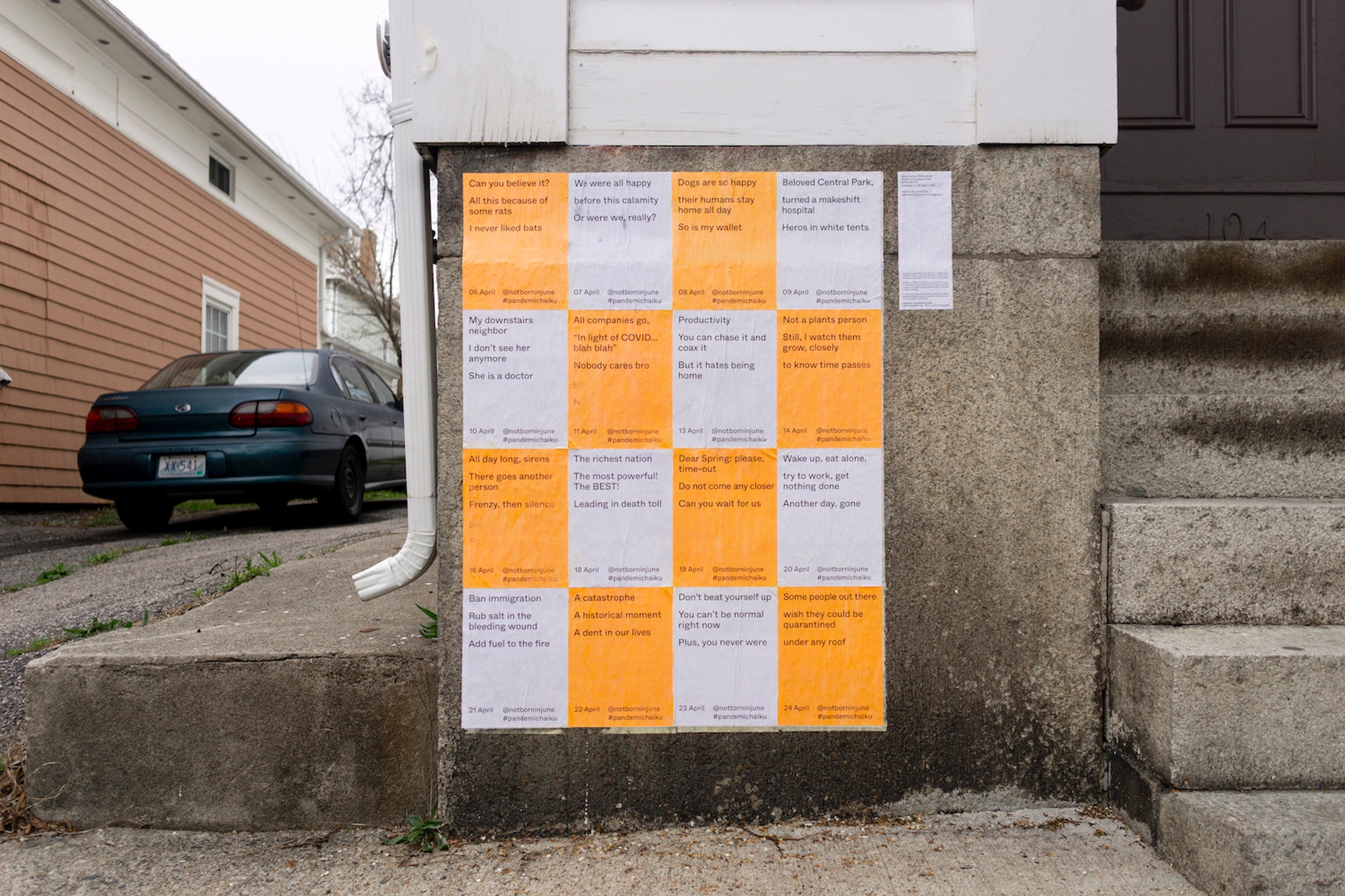

Photo: Jack Halton Fahnestock

Urgentcraft

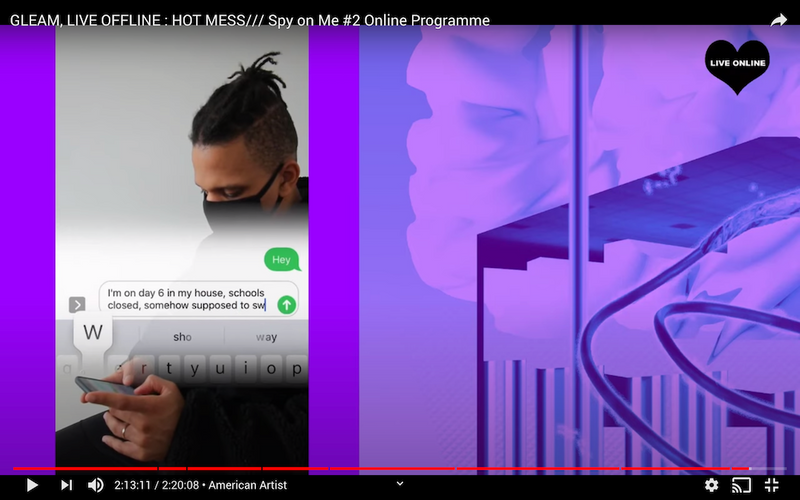

If there’s a way to characterize these acts of creative labor—work that aims to document, agitate, redistribute, or interfere with power at these pain points—I’m calling it urgentcraft. Urgentcraft during COVID-19 looks like protests happening on Instagram or within Animal Crossing, or a google doc used to collaboratively assemble work by poets, or a congressperson who makes a zine about mutual aid, or a letter demanding changes to a school as it scrambles to get a grip. It looks like a handcrafted, DIY platform that provides access to resources, support, and relief.

Creative first responders who practice urgentcraft have already been working, prioritizing equity, solidarity, and communal care practices—not top-down charity. They mobilize quickly using modest, available tools and materials, providing support, spreading information, making demands, or simply expressing the moment, despite the failures of larger structures and institutions. They go to where the conversations are already happening and that’s where they locate their work.

Urgentcraft isn’t necessarily legible to everyone; its strength is in its specificity, designed for certain communities, while barely acknowledged by others.

Demian DinéYazhi´ at Counterpublic, St. Louis, 2019 (photo: Nora Khan)

Petition for the Partial Refund of Tuition and Fees, RISD students, March 13, 2020

Radical publishing

Urgentcraft is intimately tied to independent, radical publishing. Work that carries an urgent message wants to circulate and it wants to spread. Dissemination in public is an essential part of how it works, and in a crisis, there’s no time for lengthy approvals from mainstream publishers. Artists, designers, and writers who produce urgent artifacts are working fast to create their own publics—reproducing, printing, projecting, and amplifying to smaller, specific audiences who are ready to engage in real time.

Urgentcraft means choosing to remain outside of the mainstream and the commercial. It’s a refusal to participate in normative definitions of professionalism and success, like academic publishing and the gallery system. Sometimes, this means sacrificing traditional rewards and locating your work in public space, on social media, or with your own small press, on your own terms.

As institutions crack wide open, they reveal new spaces and opportunities for reshaping and reimagining an unjust world.

For many of our leaders, a global pandemic means an opportunity to profit. But for anyone who doesn’t want to play along with disaster capitalism, urgentcraft offers a way of working below, beside, and behind the scenes, counter to professional market demands.

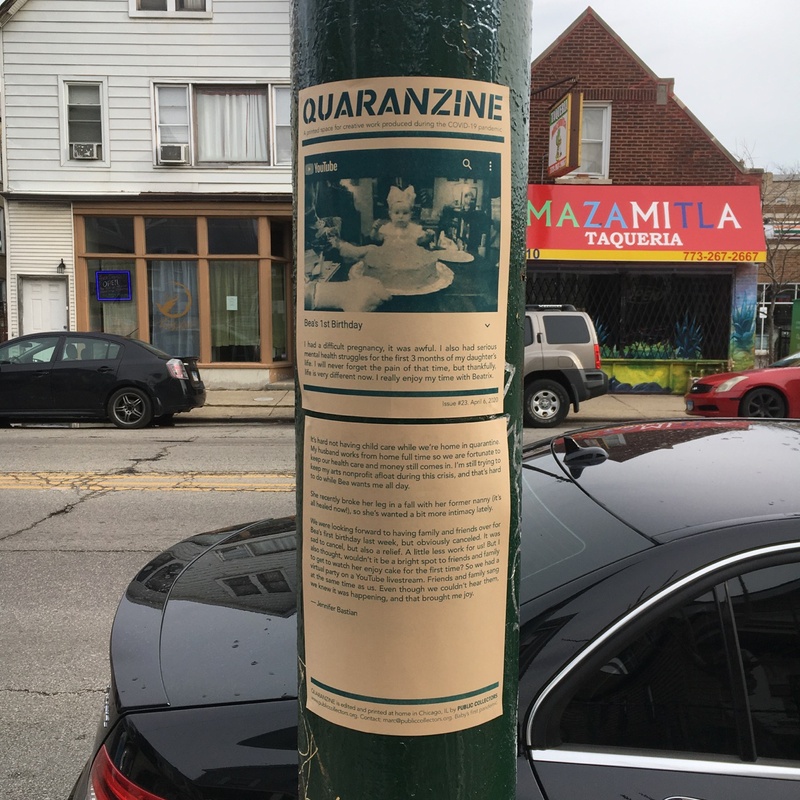

Marc Fischer, Quaranzine, Public Collectors, March–April 2020

A proposal

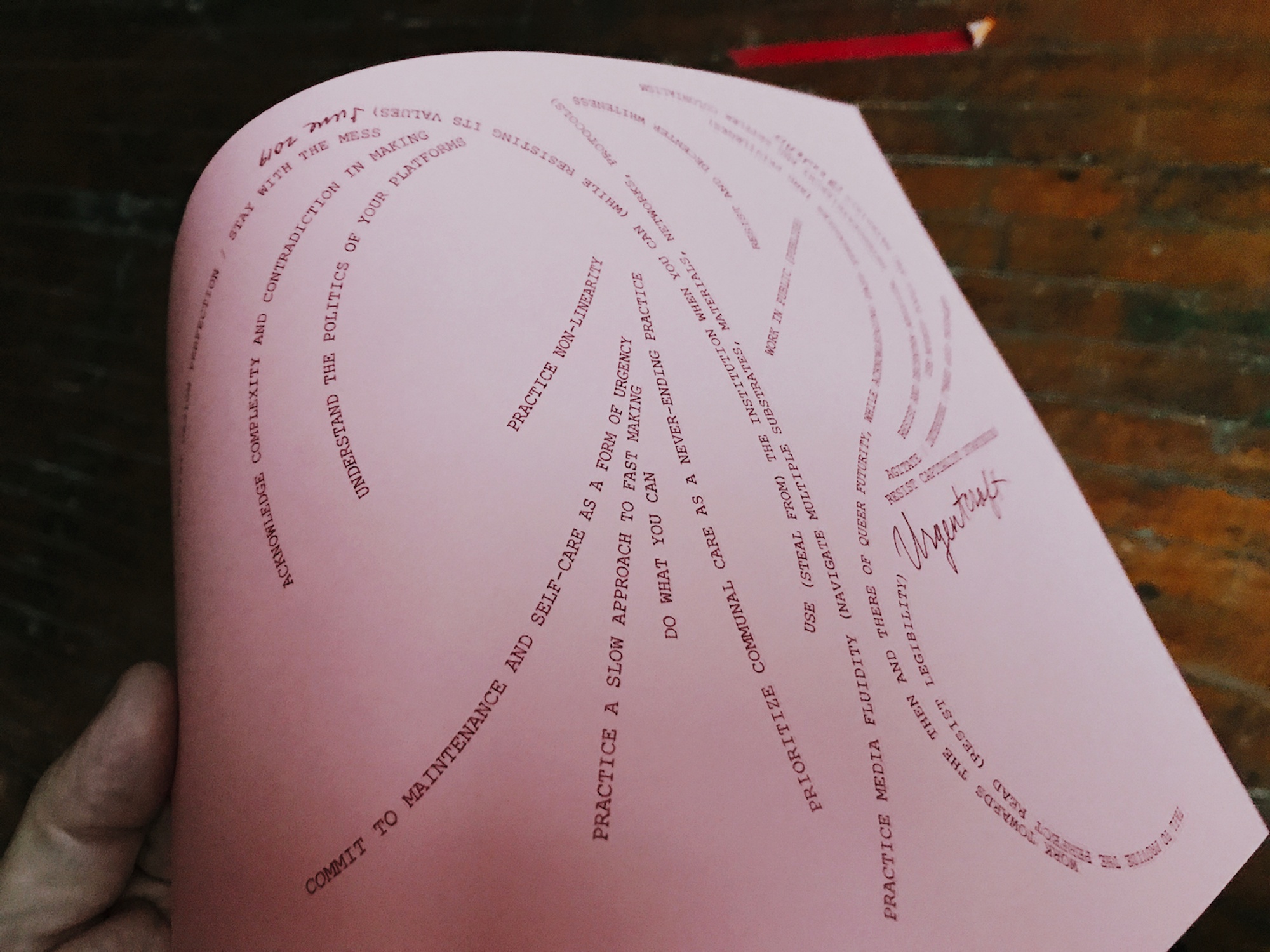

So here is a constellation of tactics to imagine what comes next, not “when the crisis is over,” but for when the harshest breakdowns are occurring. It’s a proposal to consider some of these tactics in your own creative work, like illegibility, agitation, radical publishing, and messy sense making. It’s a set of principles that works to resist the smooth flow of design perfection and oppression-based ideologies, especially for art and design students and educators. I assembled them, but they’re meant to be borrowed, distributed, used, re-circulated, and re-authored however you wish.

Principles of urgentcraft

-

Do what you can

-

Use modest tools and materials

-

Understand the politics of your platforms

-

Practice media hybridity

-

Work in public (self-publish!)

-

Practice a slow approach to fast making

-

Think big but make small

-

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

-

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

-

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

-

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

-

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

-

Resist capitalist strategies

-

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

-

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

-

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

-

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

-

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (from Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, “The University and the Undercommons: Seven Theses,” 2004)

-

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

Ongoing and persistent work

Right now, I’m prioritizing these principles in my own work and I’m keeping my gaze fixed on independent, artist-run spaces that work this way. I’m focused on non-linear, queer, anti-racist projects that agitate, interfere, and take care, that hold space for others, to amplify voices, and to connect communities. These are practices that refuse to replicate or support heteronormativity, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and capitalism. In a moment like this one, with the risks as high as they are, prioritizing communal care is imperative. The urgent artifacts that these artists create don’t wait for a crisis to peak; their work is ongoing and persistent.

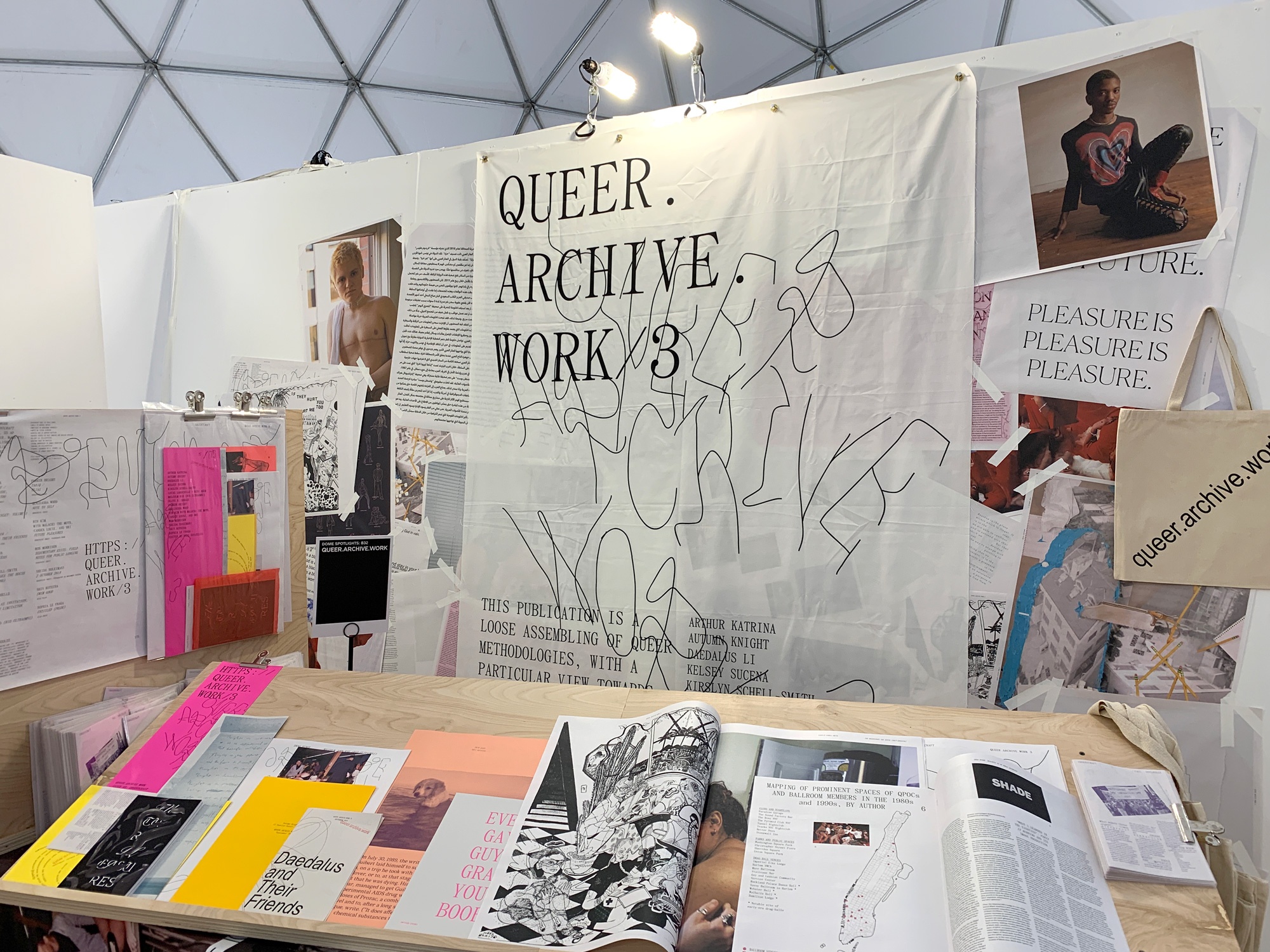

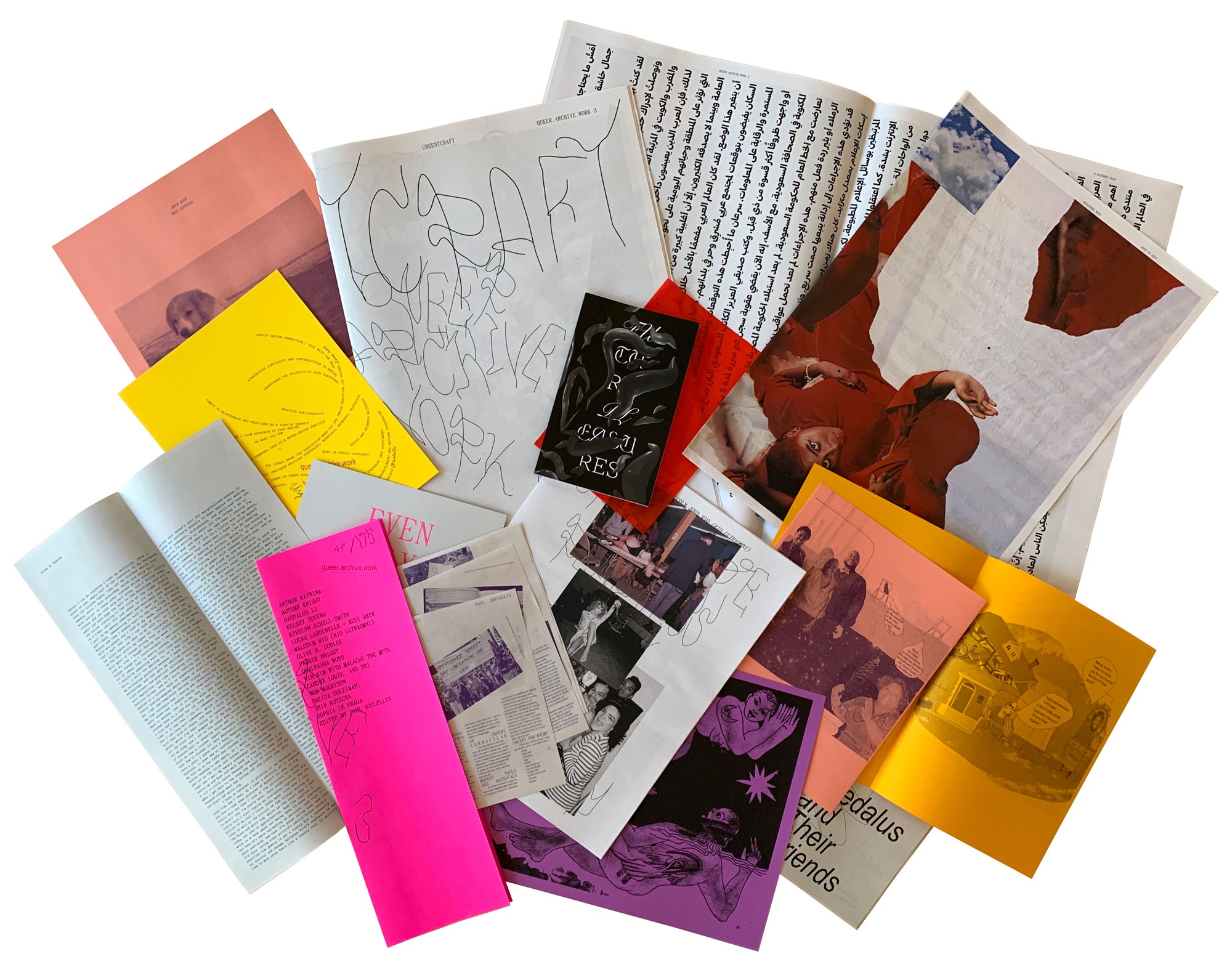

Recently, my own artist’s practice has been focused on Queer.Archive.Work, a series of projects that ask: how might a publication provide a queer space for collective care? As I’ve opened up to new networks, connecting queer theory to art and poetry to publishing communities who make good trouble with their work, I’ve tried to create a platform for voices who send urgent signals out into muddy waters, important messages that don’t comply. The publications that I release through this project are designed to make a physical mess, as the components shift around, and when they slide out of their containers.

Urgentcraft “stays with the mess” to allow for an abundance of meaning, and no dominant narrative.

A porous place

Earlier this year, I decided to transform Queer.Archive.Work into a physical space. I established a non-profit organization, and besides teaching, this is where all of my energy goes these days. I’m interested in how a gathering place can be porous; how this generous coming and going in space can work to create and support a community, and where access to tools is a form of shared empowerment (in this case a shared risograph printer in a publishing studio). This is about bringing engaged pedagogy into a more open and diverse community, away from larger institutions. It’s about physical space and the radical potential of the printed artifact.

As of February of this year, I had opened up the space, established the 501(c)3, and started turning it into a well-trafficked place, a space that would always be free to access; where productivity could be high, but expectations for success would be low, or even non-existent. It was joyful to see people coming in to work with the risograph printer, opening up access to a tool like this and empowering people to realize their work in new ways. So, we were off to a good start. Just before the crisis, I began applying for grants, and launched a riso residency program. And then, of course, I was suddenly forced to close it up to the public.

Nora Khan at work, open house printing at Queer.Archive.Work, March 2020

Mutual aid publishing during crisis

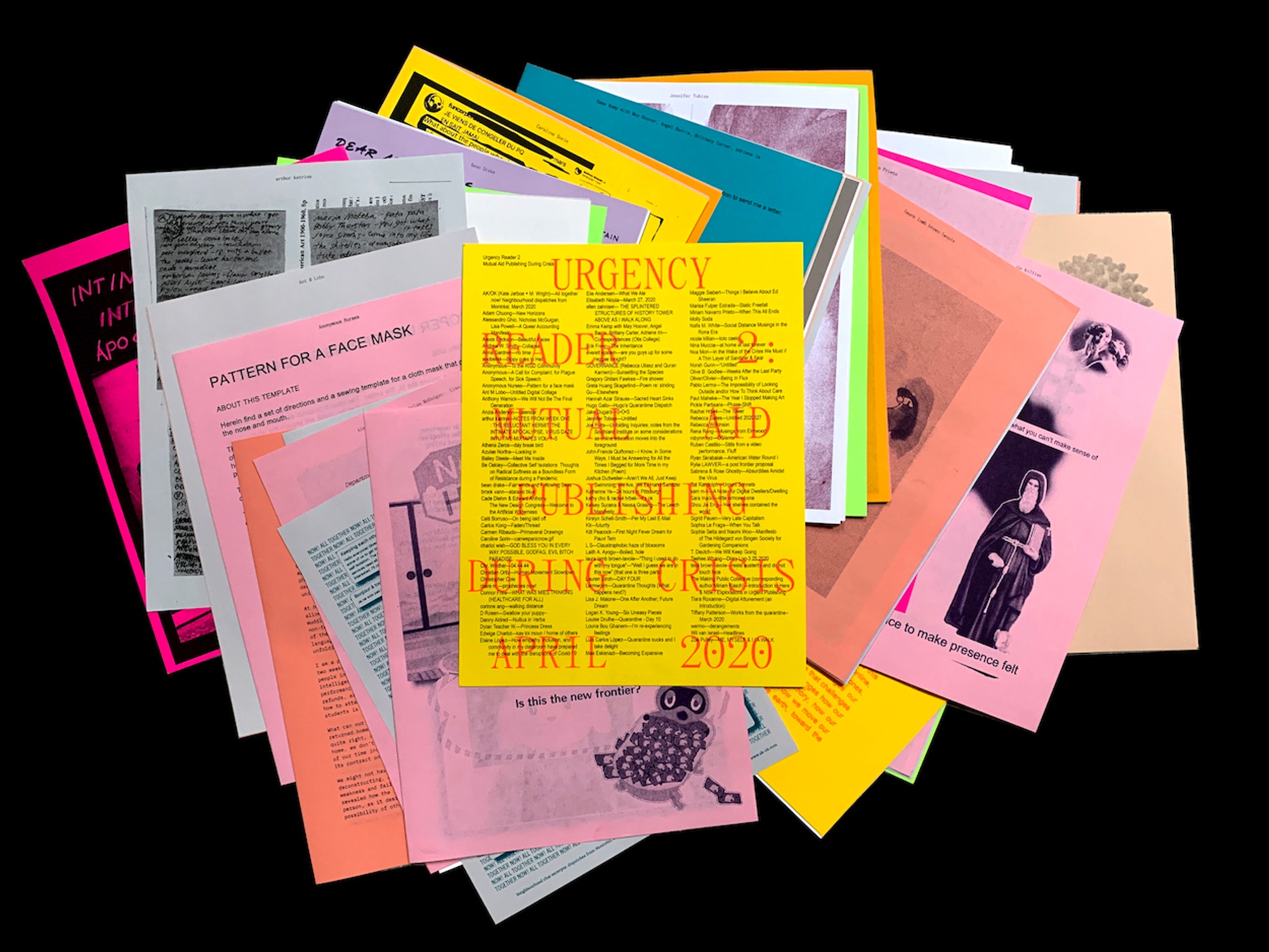

After closing our doors, I had to get to work in some other way, doing something that could happen remotely. In mid-March, I announced an open call for a “mutual aid publication:” part protest, part time capsule. I thought about how we needed to save all of this evidence being created in quarantine; that as conditions normalized later on, we would need access to this very strange mix of panic, support, and emotional expression, as a crucial affirmation of what happened.

Within 10 days of announcing the open call, I’d received over 100 submissions for what would turn into Urgency Reader 2—a dense assemblage of poetry, essays, manifestos, and other forms of expression created during quarantine. I heard from former students and friends, but mostly from artists and writers and poets who were new to me, so this was a humbling learning experience about the power of networks, and the need to be heard in this moment.

Mutual aid publishing materializes a practice of call and response, and in this response we’re in it together.

Urgency Reader 2 would be a document of this moment. With Queer.Archive.Work’s risograph printer I produced a very small edition, using all of the ink and leftover paper in the studio. I scanned one of the copies, made it available for download, and now it’s circulating. Contributors were compensated using funds from a grant I had just received, and I was able to sell the printed copies to raise funds for our risograph residencies, which start up this summer.

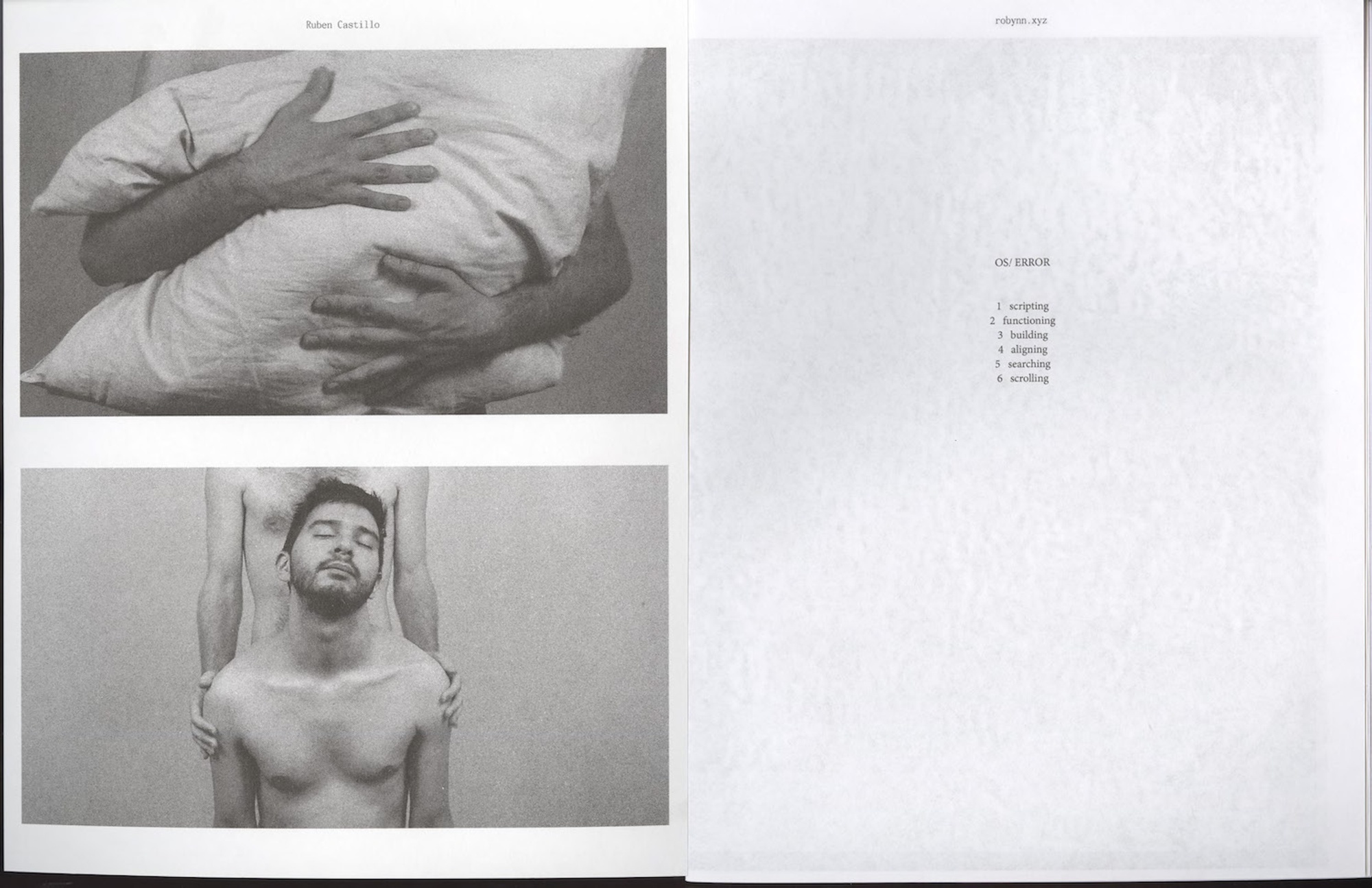

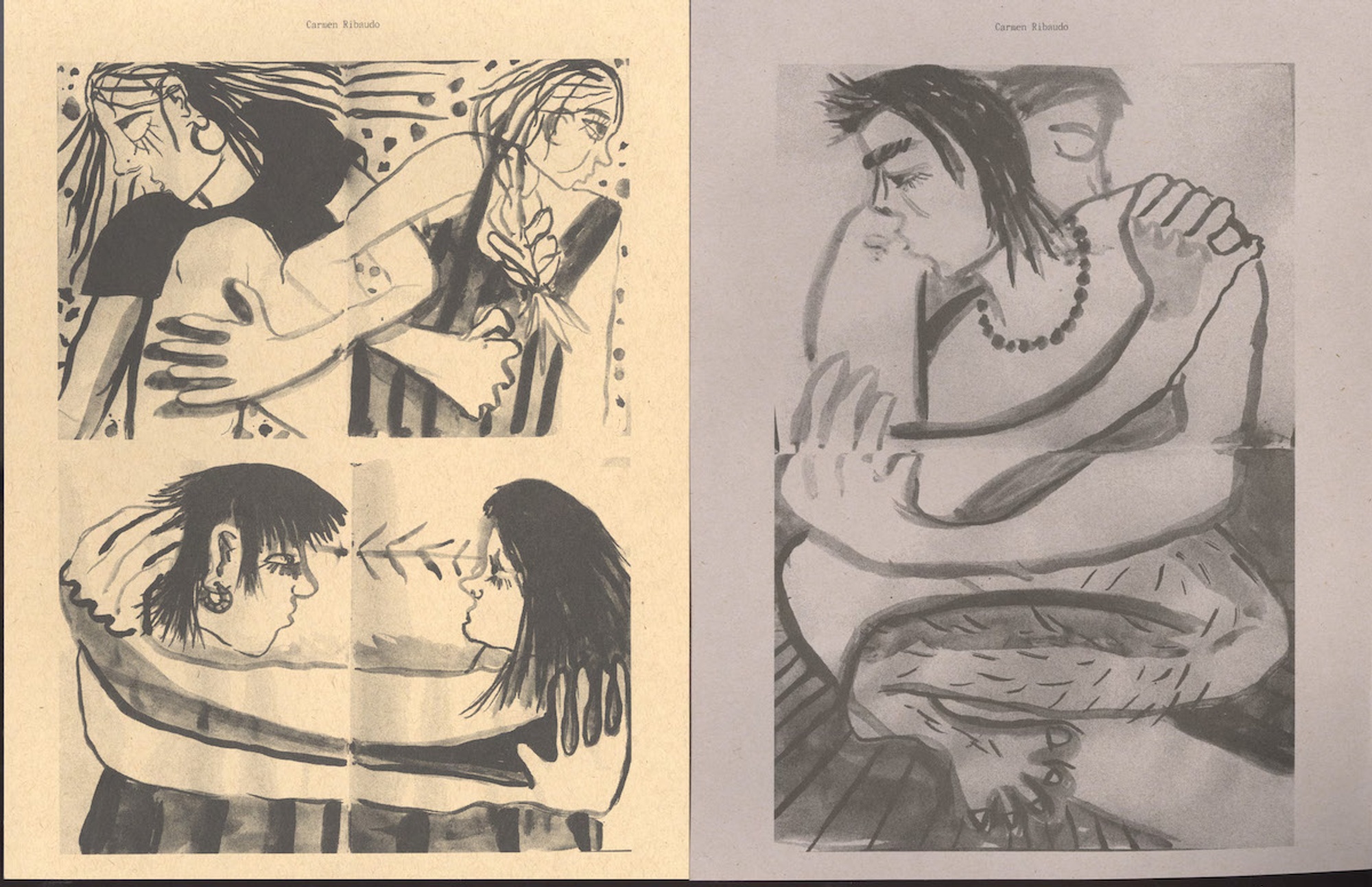

Ruben Castillo (left), robynn.xyz (right), Urgency Reader 2 - April 2020

A call to action

We’re faced with a kind of doom right now that sometimes feels like the end of the story. So here’s what you can do, in your own work, whether it be art, design, or otherwise:

Use what you have, whatever is right in front of you. Don’t wait for the next wave of crisis.

Fortify your networks now, so that when another flashpoint happens you’re prepared to connect, to call, and to respond, to gather, and to be in it together, whatever that means to you.

Map your needs. Map your assets. What are your resources? How will you share your abundance?

Be generous in how, what, and with whom you share, because in these moments of exchange, communities form.

Use the urgentcraft principles, re-shape them, add to them, share them. If nothing else, keep them around, as a reminder that art and design can be used to loosen power.

A few inspiring artists, projects, and spaces that embody urgentcraft

- Name

- Paul Soulellis

- Vocation

- Artist and educator

Some Things

Pagination