The Trap

Prelude

Charlie Curran is a New York-based filmmaker with a focus on the intersection between avant-garde culture and contemporary storytelling. He’s just finished his first feature-length documentary, See Know Evil, which he began as a student at the Savannah College of Art and Design, from which he graduated in 2013. He has made videos for creative companies including Telfar, MADE Fashion Week, New York Fashion Week, Nike, Intel, Culture Sport, and Dis Magazine.

Conversation

The Trap

On producing a feature-length documentary film for the first time, surviving youth media, and telling the story of the late photographer Davide Sorrenti.

As told to Charles Curran, 2457 words.

At this stage in my life, the most genuine story I can offer to share is my fraught experience making my first documentary film, See Know Evil, about the life and art of the late Davide Sorrenti. Sitting here only weeks after its debut, on the flip side of strong imposter syndrome, it’s challenging to figure out whether I’ve seen enough, or gained enough emotional intelligence, to offer some kind of wisdom or advice to someone on a similar path. Making my film was a seven-year-long, super windy process that took me through the highs and lows of working in “youth media.” Since there aren’t a lot of open conversations out there on this process—both on making a first film, and navigating the contemporary mediascape as a person fresh out of school—I’m hoping that sharing my lived experience might help others avoid some of the traps I fell into.

So here we go.

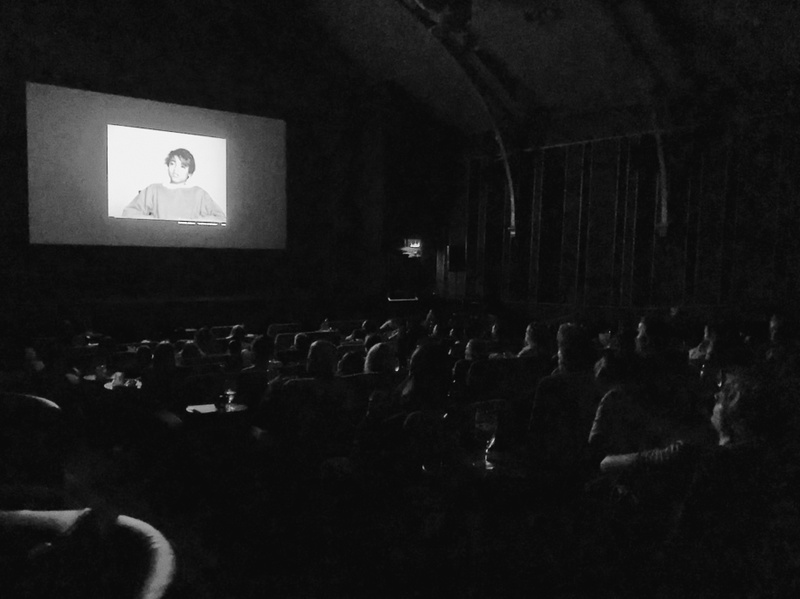

See Know Evil screening at Everyman Cinemas Hampstead, London, U.K., May 2019.

This story starts for me at age 20, studying film at the Savannah College of Art and Design. I’d hit an existential wall of sorts, and I felt hopeless. I knew I was making “student work,” but for all my worth I couldn’t understand how one went about evolving that kind of work into “capital-A Art.” I’d been making movies since the sixth grade when I first got my hands on a mini-DV camera, but somehow the experience of film school left me feeling like an absolute failure. Nine years later, I can see that’s probably something that everyone setting out in any creative field encounters. But with my student loans stacking up, late-teen angst peaking, and no end in sight, I was despondent.

Pacing the school library looking for something—anything—to pique my interest, I stopped at a table with a book left open. It was called Fashion, Desire, and Anxiety at the end of the 20th Century and was written by Rebecca Arnold. Cracking it open, I turned to a chapter about the moral panic surrounding fashion photography in the late nineties, and serendipitously started to read about the photographer Davide Sorrenti. Sitting there, at age twenty myself, and seeing the images that Davide produced at the same age, I was transfixed. The fact that another 20-year-old could be making images of that gravity shocked me, and I knew instantly that I had to “figure this out.”

I quickly learned that Davide had died at the age of 20, shortly after taking the photos that had caught my eye, and that it had been reported in the press as a heroin overdose, which sparked a media frenzy culminating in “heroin chic” becoming a household name. Little of Davide’s work had been published because he was so young when he died, and what went unpublished had been shielded by his family because of the controversy surrounding his death. Less discussed was that Davide was born with a rare form of Thalassemia, called Cooley’s Anemia, forcing him to undergo bi-monthly blood transfusions. He was also told from a very early age that he likely wouldn’t live past his 20s. When I learned that, something clicked for me. These weren’t drug-influenced images, and a 20-year-old didn’t start a drug movement. This was a kid who was forced to confront his mortality, and instead of wallowing in self-pity, he decided to express life as he saw it through his camera, as best he could.

Not knowing any better, and ever-more determined to “figure this out,” I reached out to Davide’s family and told them that though I’d never made a documentary before, this was what I intended to do. Through persistence and a bit of naiveté, I was eventually able to sit down with Davide’s mother, Francesca Sorrenti. Despite my nervousness, I told her what Davide’s work meant to me, and what I thought it would mean to other kids on similar paths—and that this was a story I felt I had to tell. She sized me up, wrote me a list of 23 names then and there, and told me that if I could cross each name off that list, by the end I’d have the story.

***

There’s an email from a childhood friend named Joe who visited me at SCAD while I was in the midst of making See Know Evil that I look back on often. It’s an anchor for me, as I think it expresses the sense of caution that’s missing from the way we make media today:

I realize it must be intoxicating to lucidly create aesthetic truth and desire. You are learning a kind of sorcery that everyday people aren’t aware of.

The central question for me now seems to be how to handle this allure. At this point, this is all I’ve got in way of suggestions: Be careful, buddy. I know that you and the people I met that weekend have loads more experience navigating and negotiating with the world that you live in, so my sentiments here probably aren’t useful. Regardless, I still feel a need to express this.

First, be careful for your own sake. After wandering the hallways for hours of both your literal house and the universe I dropped into, I saw a good deal of dead ends: Dark thoughts, lonely feelings, claustrophobic spaces, and self-destructive drives. Those experiences could easily be my own baggage. I could also see how shear disorientation, creative pressure, and the oft-shady forces of the culture industry could push someone in your position into a dark place. People kill themselves fucking around with the elemental forces at hand here.

Second, be careful for the people on the other side of your art. Ill-equipped consumers (like me) are so vulnerable to the creative forces of image making. There’s a Zizek lecture from two years back that he gave in Argentina on architecture and aesthetics. He signs off with an interesting take on a WB Yeats quote, saying basically: “As you create, tread softly, because you tread on the dreams of the people who live in the world you create.”

— Joe

***

After graduating, I thought I’d lost the plot of my film. I failed endlessly to edit it, despite having just emerged from four years of film-school education. Hitting that second wall hard, I thought what I was missing in order to complete the film were the lived experiences of being in New York and participating in the fashion industry. Feeling certain that the only logical next step in my journey was a move to Brooklyn, at age 23, that’s what I did.

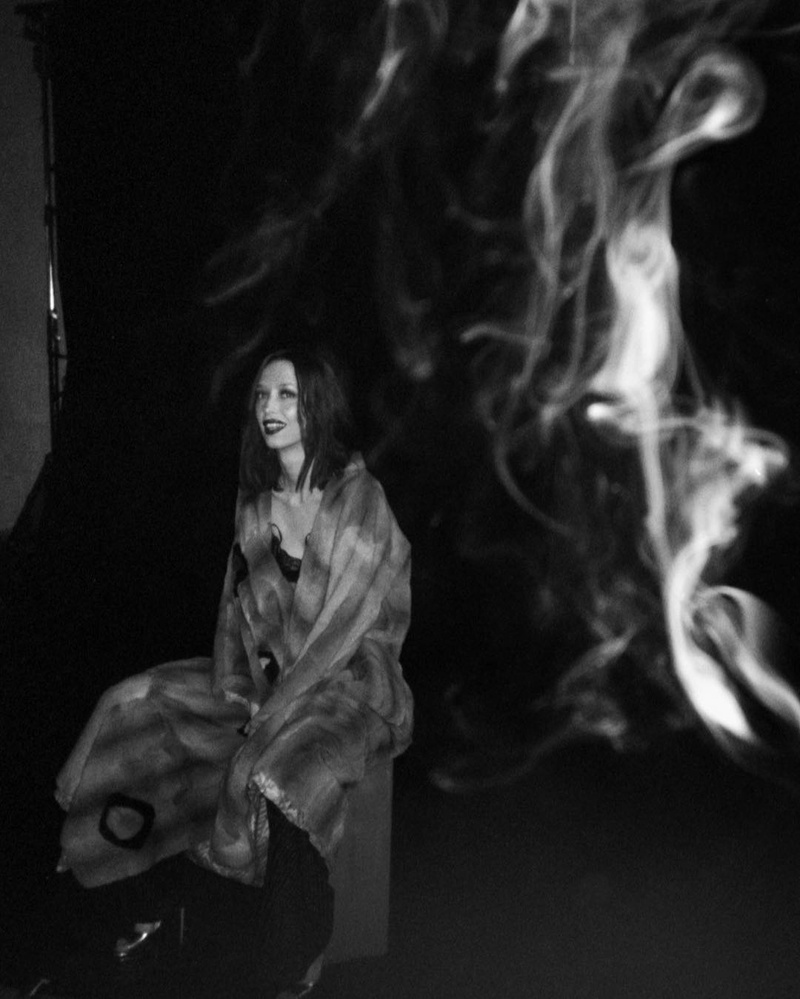

Sarah McCall on the set of Neocamp’s “Content,” photograph by Pat Bombard.

The college years.

After arriving in New York, I was lucky to meet Thalia Mavros, then Executive Creative Director at Vice Media. Her tutelage, and the other documentary filmmakers she introduced me to, were a real godsend. Working with them was a chance for me to really cut my teeth on the projects of more experienced filmmakers, and to learn all the things I didn’t know I didn’t know about storytelling. It also threw me into a brave new world of branded content and youth media. Call me naive, but I didn’t understand at the time just how “cool” was minted. Working at the epicenter of the contemporary mediascape felt like a peeling back of the curtains. As I had anticipated, it also felt like something I needed to understand in order to start fathoming the complex media landscape that Davide was navigating in 1997.

The college years.

The college years.

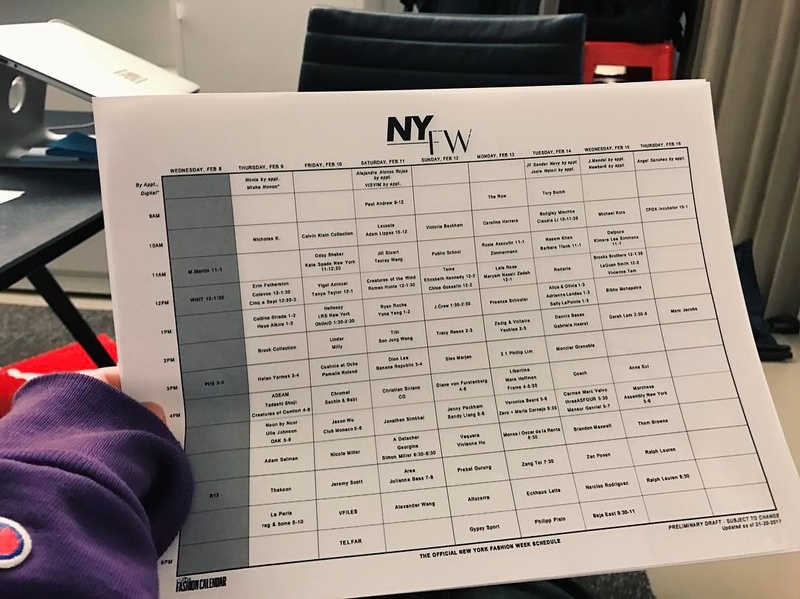

If you don’t know better, the nature of production and client-dependent deadlines can be all-consuming. Working in youth media produces rips of adrenaline, a fierce desire for accolades, and a vicious distortion of linear time. I eventually found myself shooting for MADE Fashion Week, and later New York Fashion Week, and before I knew it, I had a few hundred shows under my belt.

Your first taste of fashion week—of that rarified air—is intoxicating. This is because it’s supposed to be, and there’s a lot of capital invested to create that effect. But as you wade a bit deeper, and as you start to understand the forces at play to make these experiences and images possible, it starts to get a bit darker. If I could impart any advice for someone entering the media landscape—especially those hunting for the attention of the elusive 18- to 24-year-old demographic—it would be to drive slow, and remember that by no means is this type of work the cure for anything except putting a brand in front of fleeting eyes.

For all the crying under-age models cut from a show fiendishly ripping through honey packets on the ground, sad souls turning red shrieking to be seated at a show where they “can be seen,” or worse—this artificial production of exclusivity and glamour isn’t real, and isn’t worth it. The whirlwind of capital and spectacle that is a modern fashion week is such a hurricane of branded photo opportunities and wasted human potential that, years after exiting the scene, it boggles me still.

So hungry for youth, for beauty, for any energy that people crave to be near, the entire apparatus of the fashion machine is designed to eat its young. Wild behavior is not only excused but encouraged, and there are no real grown-ups in the room—only clients and sponsors hoping for a write-up about their after party.

It seems obvious enough writing this now, but inside this machine, attempts to measure your self-worth against any reference point will send you spinning sideways. This makes people do all sorts of strange things.

New York “Content” Week incarnate.

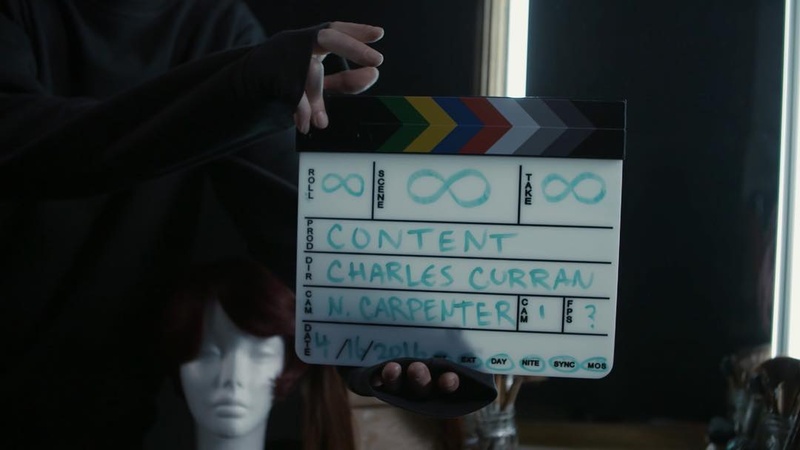

Still from Neocamp’s “Content,” 2016.

Fake realities will create fake humans. Or, fake humans will generate fake realities and then sell them to other humans, turning them, eventually, into forgeries of themselves. So we wind up with fake humans inventing fake realities and then peddling them to other fake humans. It is just a very large version of Disneyland. You can have the Pirate Ride or the Lincoln Simulacrum or Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride—you can have all of them, but none is true.

— Philip K. Dick

Kanye doesn’t pose, but he’s really kind in person.

New York Fashion Week, SS-17.

Existing inside the fashion world is a rush because it’s meant to be. And that’s the trap. The value systems dart so quickly, and the interactions are so transactional—all in the aid of this grand image-making event that burns so bright, people get lost in the glow of it all. And I don’t blame anyone for wanting to wrap themselves in the allure, take a picture with Kanye, or be somewhere someone else can’t be. The media generates these cyclones and perpetuates these ideas. It’s just not real.

***

Eventually (and thankfully), I hit my next wall with the film. Though it’s always painful at the time to hit these seemingly insurmountable barricades along the way, they’re necessary—unavoidable even—and I’ve come to appreciate them as just part of the creative process. The more time I spent inside this fantasy-printing machine, the more obvious the associated costs became. That I had to fall for the glamour, throw myself into the belly of the contemporary-youth-media beast, and make it through enough of these hyper-capitalized dances to understand how these structures function in order to really understand the forces at play in Davide Sorrenti’s story seems obvious only in retrospect. But that’s probably always the rub.

Living with Davide’s story for so long though, I had him as a guide of sorts while putting myself through these experiences, and for that I’m very thankful. Davide always said that he wasn’t a fashion photographer, and that fashion was something you did to get money to do your own thing. He understood how it all worked, and he was able to use that and navigate it deftly enough to get his art through the machine. So I tried my best to do that and follow his lead and in this case, at this point, I think I finally got away with it.

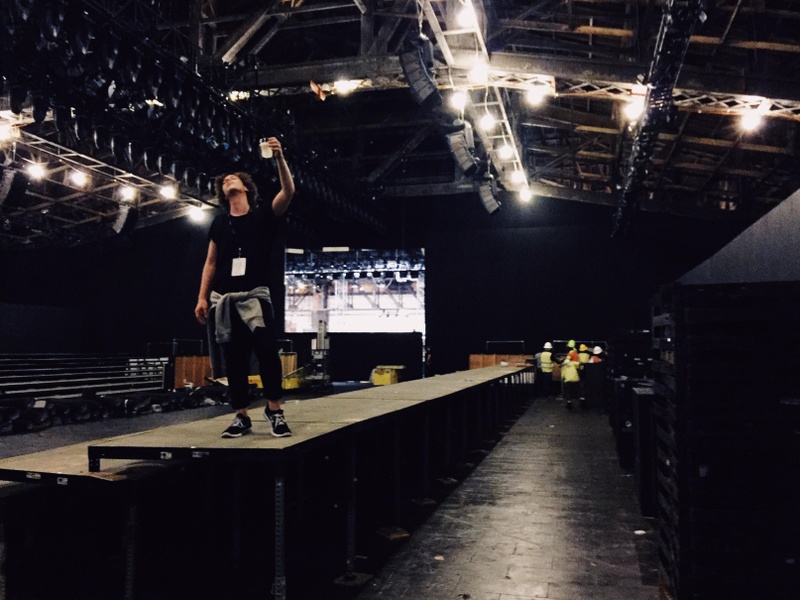

Buildout of the “Telfar: Retrospective” for the 9th Berlin Biennale, Berlin 2016.

There’s a quote by the late Mark Fisher about the culture industry in the late ’70s that I think expresses this idea I learned from Davide far better than I ever could. It reads:

Mass culture—and music culture in particular—was a terrain of struggle rather than a dominion of capital. The relationship between aesthetic forms and politics was unstable and inchoate—aesthetic forms did not simply “express” some already-existing capitalist reality, they anticipated and actually produced new possibilities. Commodification was not the point at which this tension would always and inevitably be resolved in favor of capital; rather, commodities could themselves be the means by which rebellious currents could propagate.

— Mark Fisher, Kpunk: The Collected Writings and Unpublished Works of Mark Fisher

That’s the flip side you always need to keep in mind when you interface with these systems of manufactured culture, or stories, or dreams. They can be a catalyst, a resource, or a platform for anything—positive, neutral, or negative—depending on how it all shakes out. If you understand how they function, why they function, and how to navigate them, you have a chance to get through it in one piece with what you’re trying to bring into the world. But if you don’t, it’s easy to get lost along the way. That’s where the real danger lies—both for you, and for the people on the other side of your art who don’t understand why the dreams for sale are what they are, but who end up stuck living in them anyway.

There’s a lot of beauty and creativity in the fashion industry, and in youth media in particular. Some of the smartest, most talented, and most creative people I’ve had the pleasure to meet and work with do what they do best in that scene. Also some of the most insecure and self-destructive. Being sensitive enough to excel in the arts, and placing yourself at the mercy of those commercial forces, brings everything out.

- Name

- Charles Curran

- Vocation

- Filmmaker

Some Things

Pagination