How to begin designing for diversity

Introduction

We’re Jahan and Boyuan, co-founders of Project Inkblot, a team of designers and futurists who partner with companies to build equitable products, services, and content. To make this happen, we use Design for Diversity™(D4D)—a framework we developed that enables you to make better work by illuminating cultural and racial biases within your design, ideation, and creative processes.

How’d we end up here? As women of color and consultants, we’ve worked on everything from designing programs for entrepreneurs to marketing campaigns for the HIV/LBGTQ/homeless community. Throughout our past work, we consistently noticed that the people these campaigns aimed to reach (namely POC, women, and other misrepresented communities) were rarely part of the design or creative process—which was a big problem. As Project Inkblot, we’re working to create a mindset shift that helps people move away from creating only for dominant culture, to instead create with and for all.

In order to create for all, we have to employ processes that authentically engage misrepresented communities. People tend to think of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts in terms of implicit bias workshops, employee resource groups, and hiring processes. These efforts are all important, but we focus on DEI as action—as it relates to the creation of products, services, and content—and use a design-thinking approach to tackle these tricky issues.

Our belief is that the future is present—for instance, “minority” young people under the age of 18 will become the “majority” by 2020. For our work and world to thrive, we must all be leaders in designing an equitable future. We hope this guide will give you an overview of how to prepare for the future by building diverse perspectives into the creation process of whatever it is you do or make.

— Jahan + Boyuan of Project Inkblot

Building a shared language

A quick note about the word “design”

You’ll notice we use the word design a lot. When we say design, we’re not just talking about graphic design or website design. It’s broader than that, because all of us are designers. You designed the route you took to work just as you designed what you ate for breakfast, and those decisions were made consciously or unconsciously. That’s powerful because it means you have agency. It means you can begin to locate and re-design what may be inequitable processes in your work.

As you read through this guide, we invite you to think of yourselves as designers and to start getting curious about how you create, and the types of people you bring into your process. This could include taking a deeper look at who you bring onto your team, the stories you curate on your website, the campaigns you produce, or the technology you make.

D4D definitions

We’re aware language continually evolves, and so for the purpose of getting on the same page, let’s establish some shared definitions, shall we? (Keep in mind that these definitions are specific to our work and how we’re using the words in this guide—there are many other ways to define these terms.)

DESIGN is the creation of a plan to build an object, system, or human interaction.

DIVERSITY is quantitative. It’s the composition of different people represented in what you make, and the decision makers on your team.

INCLUSION speaks to the quality of the experience you’ve designed for these diverse folks, so they experience themselves as leaders and decision makers.

EQUITY lives in how we design our systems and processes; the way we work, and who we work with, so we are upholding our commitment to diversity and inclusion.

FRAMEWORKS are the basic structures that enable complex systems to function.

MISREPRESENTED COMMUNITIES are communities that have been defined by dominant culture, denied the ability to define themselves on their own terms, and are therefore falsely or narrowly represented. We use this instead of “underrepresented” or “marginalized,” because those identifiers again center the POV of dominant culture.

Why use frameworks to design for diversity?

Frameworks are used in various industries to help folks avoid mistakes, especially when engaging in fast-paced, high-stress work. In The Checklist Manifesto, surgeon and author Atul Gawande writes about being inspired by the pilot’s checklist, a type of tactical framework used in the aviation industry for takeoff and landing, as well as emergency procedures. The pilot’s checklist isn’t just about order of operations—instead, it’s a way of thinking about preparation, accountability, and teamwork. Gawande also speaks about introducing the surgeon’s checklist into operating rooms to remedy a bunch of awful and avoidable mistakes that were occurring—things like inanimate objects being left in patients’ bodies post-surgery (yes, that’s a real thing). In essence, the checklist is a series of checks and balances that are rooted in the question, what could go wrong?

We love this idea because it assumes that while surgeons are experts, they are not infallible. So many of us work and create in high-pressure environments. Left unchecked, our biases can seep into how we create in ways that exclude others and cause negative and even dire outcomes. You may be thinking, “Well, pilots and surgeons are working in high-stress environments where people’s lives are at stake. I’m an artist and an entrepreneur, I’m not saving lives.” But there are countless examples of the impact of racial and gender bias in media narratives, and in the way we build technology, like self-driving cars that fail to detect dark-skinned pedestrians, which then can become a matter of life and death.

This is not a new problem. In fact, Kodak has a history of creating film stock where white skin was used as the ideal tone, which created problems later on for how darker skin showed up on camera. This same lineage of racial bias in design is now prevalent in biased algorithms. Many of these examples did not start maliciously, but that’s the point—if dominant culture is used as the norm from which we create and design, then we will undoubtedly end up excluding everyone else.

And yet, this is an exciting time! Our increasingly diverse, multi-ethnic, multilingual world is becoming less tolerant of bias and more impatient for change. We can mitigate these mistakes by thinking critically about DEI from the start, and using the D4D framework to create checks and balances.

What’s the Design for Diversity™ framework?

The D4D framework is made up of tools and critical thinking exercises that can be used in any creative process to illuminate where racial and cultural biases show up. The reality is that we all identify in specific ways based on our life experiences, whether we’re conscious of it or not. Those life experiences can lead us to specific perspectives and biases. Those biases influence how we work.

Left to our own devices—and without thinking critically about who we are, how we create, and who we are creating for—we can make some major mistakes. A misguided content idea can offend an entire gender, a marketing campaign can alienate an entire race, a new technology can create undue harm to an entire demographic of people. Sometimes it’s immediate, but more often, the repercussions of these mistakes can build over time in insidious ways that are challenging, and sometimes even impossible, to undo.

At the same time, just as the pilot’s and surgeon’s checklists can’t prevent every potential error, D4D is not a cure-all for racism, sexism, homophobia, or any other -ism. It is a way-finding tool, an opportunity to stop and think as you move through your own process to clear the path for excellent work.

Core questions to consider in your design process

As you begin to tackle the question of designing for diversity, we’ve distilled our larger D4D framework into the below core questions that will help you think through your process:

Core question #1: What’s the worst-case scenario, and on whom?

What we’ve noticed over many years of consulting is that people love to jump into strategy! We get it. It’s a fast-paced world, and we want to create solutions—now. However, moving too quickly is one of the greatest culprits for making mistakes. One way to slow down your process, and break through the first layer of bias, is to ask the brainstorming question: what’s the worst case scenario, and on whom?

This exercise begins to illuminate who and what we may not be thinking about, as it relates to the impact of your work. We cannot predict the future, but using this question is a great way to start expanding your thinking. Building a cadence of returning to this core question at different stages of a project is important, because it helps you get in the habit of proactively analyzing the potential impact of your work, and over time, realigns your brain to a different way of thinking.

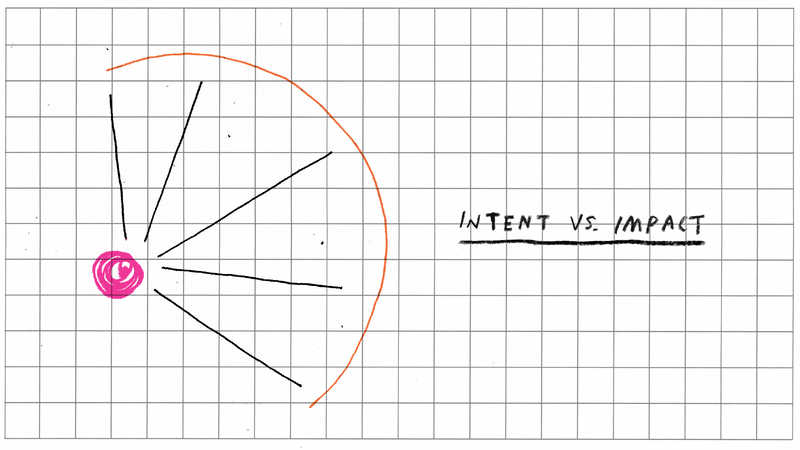

Most people think of their impact as their intention, but those two things are actually quite different. Here’s how:

- Intention is personal to you and your team, and what you hope to achieve.

- Impact is how what you make is lived and experienced in the real world in actual communities.

- Intent does not undo impact!

So how does this live out in practice? You can do this brainstorming exercise as a group, in pairs, or individually, but we highly recommend doing this exercise with your team. The more diverse eyes and brains are in the room means more people are going to see what you don’t. Start brainstorming on what the worst case scenario could be for your work’s impact, and the communities of people it could affect. Follow up on this brainstorm by thinking through the best case scenario, and who that benefits. Take some time to review the team’s feedback. What are the differences in people’s answers? What are the similarities? Based on what you’ve learned, where can you see opportunities to shift your strategy?

Consider the example of restaurants going cashless. The great “convenience” that excited millennial restaurateurs ended up being banned by multiple cities because these technologies discriminated against older, POC, and low-income patrons. Had they incorporated a habitual exercise to consider their intent vs. impact at multiple stages before and during the rollout, they could have determined this blowback much earlier.

Core question 2: How do the identities within your team influence and impact your design decisions?

When we join forces with a collaborative group, we each enter with our own values, priorities, and goals—in addition to the cultural and racial identities we bring to the table.

In the strategic-thinking framework called Design Thinking, a common problem-solving technique is to approach challenges at the start of ideation by asking questions framed by, “How might we…?” This enables teams to brainstorm fresh approaches to their challenges, without feeling too boxed in or constrained. In our work, we like to pull it back before we even get there, and ask our team, “Who are we?” Understanding who’s at the table—and how these stakeholders will influence the design process—is a crucial first step. Answering this question will require your team members to be a bit vulnerable, but it’s worth talking through to get clear on the various perspectives present.

With your team, consider the following questions for your work/project:

- What are your top priorities for this project?

- What do you value when working with others? Name three behaviors (e.g. integrity, honesty, open communication)

- What race(s) and gender(s) do you identify as? What other ways do you identify, that are important to you? (e.g. queer, Latinx, middle-class woman in my 30s, aunt, grew up in a military family, etc.)

- How might these identities influence and/or inform how you design products or services?

- What perspectives or lived experiences might be missing from your team?

Taking time to share your answers at the start of a creative project provides valuable insight on what you’re paying attention to, what’s important to the team, and whose perspective may be missing.

Core question #3: Who might you be excluding?

As you’ve developed your product, service, or content, you’ve probably spent time thinking about your target audience. Most creatives are building solutions to challenges we’ve personally experienced, or for people who look and feel like us. Because of this, we don’t usually think about who we might be excluding. But using D4D, we have the opportunity to consider everyone from the onset.

For example, you may say: “I’ve created a program for women writers to enter the publishing world with fewer barriers. To design for diversity, do I need to include men now?” Well, no—you’re building a service for a group that is already misrepresented, and you’re speaking to a specific need. However, it’s important to be clear on who else you might be excluding, and why.

A brainstorming tool we use to help teams suss out a situation like the above is the “All People Statement” from the Results Based Accountability framework. The purpose of using this statement is to help expose who tends to be excluded from experiences like the one you’re developing, by imagining an ideal condition of being for all people, and then seeing where that statement proves false. An example of an All People Statement applied to the earlier example would be:

“All People have access to the resources needed to get their writing published.”

When you use the All People Statement in this way, it exposes the reality that all people do not currently have access to the resources necessary to get their writing published. The next question would be, “Who does not typically have access to opportunities in the publishing world?” You and your team would start to brainstorm different communities with limited access. As we follow this process, we’ll see there are many additional misrepresented groups beyond the blanket term “women” who we might not have considered. For example, women of color, lower-income folks, people without higher degrees, etc. The point is, you can start to see who you might be excluding, and then you have the opportunity to ask yourself why.

By starting with the All People Statement exercise, you may discover that although your mission is focused on getting more women writers published, you’re mostly catering to upper-class, educated white women. Your team may also notice that while you’re catering to people who define themselves as women, you’re excluding the trans and/or non-binary community. You may start to notice this bias reflected in your messaging, in the homogenous images you’ve curated for the site, and so forth. This is a simple example, but you get the idea.

Once you’ve discovered where your biases live, do you have to shift your tone and content to speak to the groups you were previously excluding? Well, no—but it’s the smart thing to do if you want to be relevant, reach a wider audience, minimize harm, and create higher quality work.

Core question #4: How will you engage the people you want to reach within your design process, equitably?

Becoming aware of the perspectives that might be missing from your team allows you to start thinking about what we refer to as “The Source Community” (or “The Source”). They are broken into two segments: the Target Source and the Excluded Source.

- The Target Source are the people we intentionally want to reach—i.e. our “target” demographic or ideal customer.

- The Excluded Source are communities we may not necessarily be thinking of reaching, but who may interact and/or be impacted by our product, service or content—often negatively.

As you begin to design for diversity, it’s crucial to ensure you are recognizing perspectives from both the Target and Excluded Source.

So, how might this play out? As an example, we worked with an organization whose mission was to provide IRL professional development programming for women entrepreneurs. Through our partnership, they discovered they were largely targeting networked, educated, millennial white women as their Target Source. However, in reality, the fastest-growing group of women entrepreneurs are actually low-income women, women of color, and immigrant women. This group is what we called the Excluded Source, a group that is often overlooked but could interact with/be impacted by this program. By overlooking these communities in their design processes, the impact on them was most likely going to be negative. For instance, if a low-income immigrant woman entrepreneur who was interested in opening a neighborhood clothing boutique saw that the only finance related programming was about securing venture capital, that not only would have overlooked her needs, but could have created an alienating experience for her. This discovery led to this organization bringing on Excluded Source members as leaders to shape the mission and content of their programming. These shifts in more culturally responsive programming led to more diverse audiences, which led to a much greater turnout, which led to a greater level of success.

How to engage the Excluded Source

When reaching out to misrepresented people, we know there’s a real fear of tokenizing. To start to bridge this gap, begin with an open conversation using honest language that establishes trust and speaks to what’s in it for them. For example:

“If you’re open to sharing, I’d like to learn more about you and your interests and invite you to be a leader on this project. Would you be interested in this, and conversely, do you have any concerns? What would make participating in this project a win for you?”

When we engage communities who have been exploited and have historically had less decision-making power, we must invite them into the process in a way that acknowledges we are thinking about how they can benefit. Acknowledgement can come in many forms! It can look like financial compensation, a position on your advisory board, decision-making power, a byline, etc. There are many creative and fulfilling ways to create equitable partnerships. Starting by asking what would be a win for them—and then really listening to their response—shifts the tone from transactional to one of partnership.

Core question #5: Is the ongoing process of improving your product/service informed by The Source?

Designing for diversity isn’t a “one-and-done” practice. As your content shifts, make sure you’re continuously evolving alongside the feedback of the Source Community. These communities are often furthest from institutional power. Their voices are rarely invited in or valued as decision makers. Especially if you are creating something that directly speaks to them, their leadership is not just a nice bonus—it’s a critical part of your work.

Let’s say you’ve spoken directly to The Source, you’ve gotten useful feedback, and you’re feeling good that you’re designing with equity in mind. Now you’ve got to ensure you have a plan to sustain this approach over time.

Some questions to consider for long-term DEI success:

- Is there a process in place to review iterations of your product/service with The Source?

- If not, what could that look like?

- Who on your team will ensure this?

Common pitfalls of designing for diversity

Adopting new behaviors and breaking old habits that counter dominant culture is not easy, so it’s important to be aware of some of the pitfalls that can thwart designing for diversity. These challenges usually manifest in individuals’ attitudes and behaviors, such as:

- Believing you’re the “expert”

- Fear of saying the wrong thing

- Being attached and controlling every decision

- Fear of engaging with communities you’re unfamiliar with

- Savior mentality; not truly believing people are capable of helping themselves

- And many more!

Using the D4D framework increases our awareness of these pitfalls, and can mitigate unnecessary mistakes. So while this is bigger than you, you still have the agency to shift your own creative practice and the practices at your organization. With a critical mass, we can create equitable systems at scale.

Remember when we spoke about the surgeons checklist? It wasn’t easy for Gawande to introduce the idea of a checklist to doctors. Many surgeons were offended by the idea—they were doctors, after all. There were other types of resistance, as well. Due to the gender dynamics between many doctors and nurses, the majority-women nurses felt uncomfortable asking the majority-male doctors to use the checklist. So let’s be clear: what male doctors had to contend with was not just their ego around using a checklist. They had to contend with taking orders from women, and that points to a deeper conversation around how we are socialized to view misrepresented communities.

This is why the practice of designing for diversity can be challenging: because it asks us to contend with the things we often don’t want to examine, and to redistribute power. It asks us to invite in partnership as opposed to dominating, and to be accountable for what we are building, considering the difficult questions of, “Who am I? How do I create? Who am I excluding, and why?” Designing for diversity gives us the opportunity to bring in various perspectives, to build things that include more expansive narratives, and to create products, services, and content that work for all people—not just a few.

But back to Gawande. While these unforeseen barriers proved challenging in shifting the behavior of the medical industry, significant strides have been made in the use of the surgeons checklist. Teams began holding one another to a higher level of accountability, leading to better patient experiences, and ultimately, more lives saved. In the same way, our aim is to have Design for Diversity™ be the standard practice for how we design everything!

As you get started in designing for diversity, here’s a handy D4D work-planning checklist you can print out and use with your team.

In summary…

It’s vital to understand the role our cultural and racial biases play in how we interact with others, how we build our teams, who we view as experts, how we create, and for whom. Yes, this is about building an equitable future for all— and it’s also about opening up pathways to our own creativity by considering nuances, and working with people who can see what we cannot. Whether you’re a solopreneur, a studio artist, a non-profit leader, or a creative technologist, you can use D4D to develop and adopt a diverse, equitable, and inclusive lens to improve the quality of your work and make it culturally adaptable to our world.