How to embrace mistakes without romanticizing failure

Introduction

In recent years, a lot of creative people have spoken out about failure. It has inspired TED talks, books, and podcasts, and its discussion has entered mainstream culture. In all of these conversations, however, we rarely acknowledge that people who gain a lot of attention for talking about failure are, by and large, successful. We listen to them precisely because they’ve already achieved some level of notoriety and good repute. Indeed, those who may be most “qualified” to discuss failure wouldn’t likely have a platform to do so.

Failure, by definition, is lacking success. Yet the word has transformed into a catch-all for “difficulty” and “setback,” from which an ultimate triumph must follow. In other words, when we talk about failure, we’re really talking about success, and how to get it. We celebrate taking risks and making mistakes, but don’t point enough at the uncomfortable truths that surround our longing for achievement. In addition, we seem to miss the point that having the luxury to make mistakes is a privilege.

During my career, I have started a number of projects (a podcast, a doodle series, a small book, a long-distance relationship) that have failed. I have also applied to jobs, conferences, and grants I haven’t received. I wouldn’t say such rejections make me a failure, but they have triggered insecurities and harsh self-criticism. In writing this guide, I hope to present a workbook of sorts, which may be useful in exploring our personal notions and histories of failure. Hopefully, it will help you avoid idealizing both struggles and successes, resist the constant search for external recognition, and create the groundwork for getting to better know your creative self, your needs, and what fits you best.

— Juliana Castro

What is failure?

On paper, failure is about malfunction. According to Merriam Webster, it is a state of inability, an omission, or a lack of success. It comes from the Latin fallere which means to disappoint. Failure is never defined as a feeling, nor is it articulated as part of any process (and certainly not as a step towards an accomplishment).

But failure feels like a feeling. Is real failure about expectations and imaginary failure about feelings? What’s the difference between a dramatic failure and a generative setback? Can we claim to have failed only when the consequences are visible to others, unforgiving, and lonely? Is there such a thing as a failure that only exists in our mind, and is hard to explain to those who can’t see our feeling of inadequacy?

Maybe errors are part of the potion for both success and failure. Maybe a dramatic failure is a just series of stubborn mistakes that didn’t get therapy. In any case, like with all things therapy, it might be about malfunction, but it is not about blaming.

In order to reconsider what it means to “fail,” what follows is a set of tactics you can use to try to renegotiate your relationship with failure.

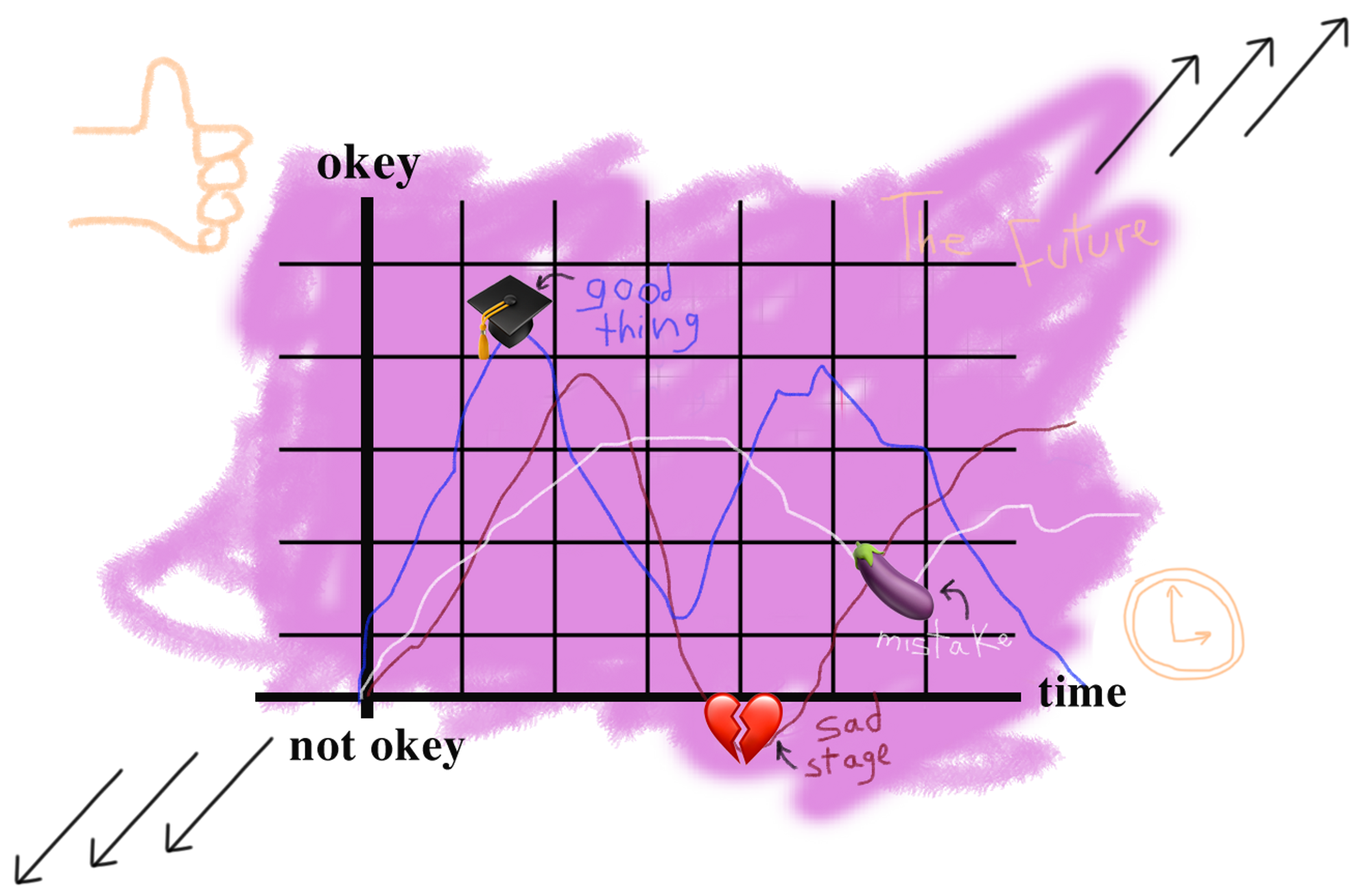

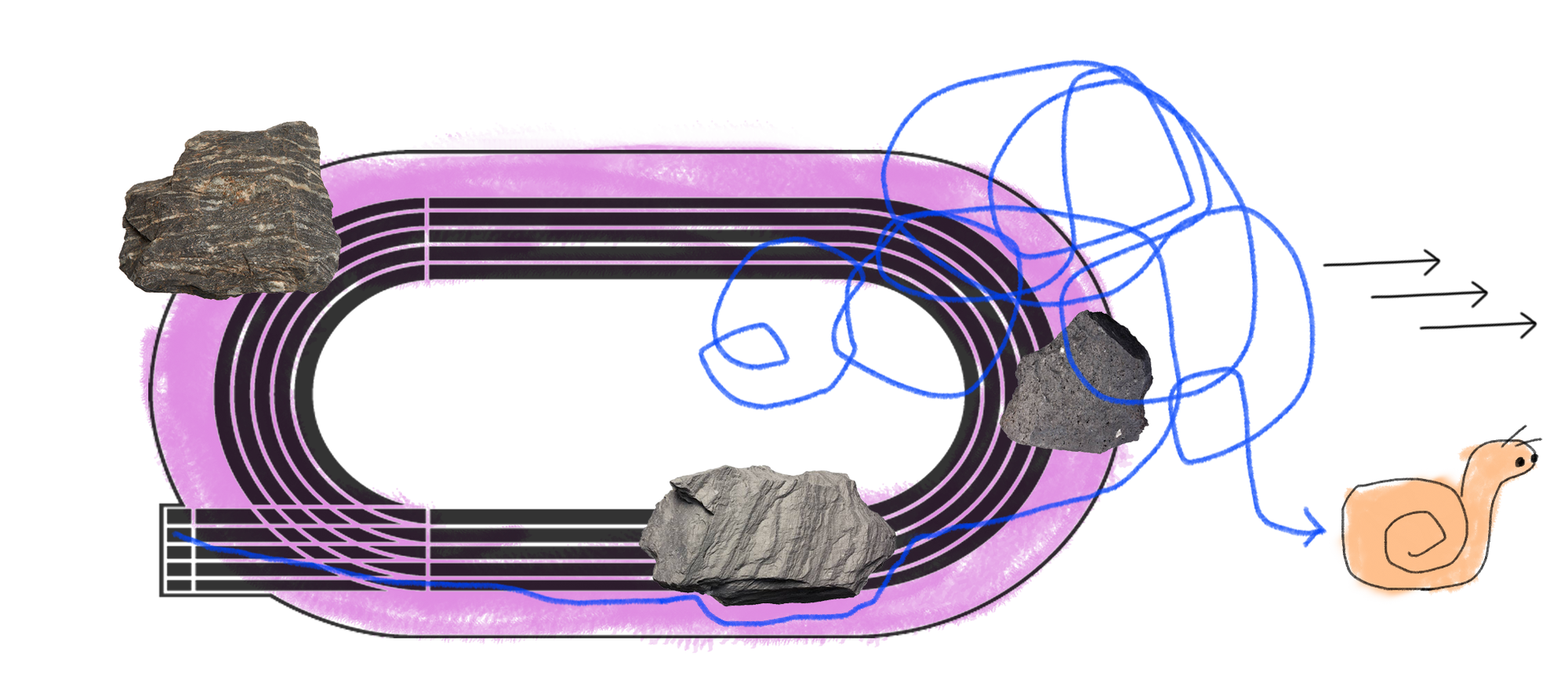

Tactic 1: Make a timeline of feelings and mistakes

Map out your creative life starting whenever you think it’s important. Include lines for expectations, accomplishments, mistakes, and feelings. Try your best to mark the ups and downs. Accommodate all sorts of little triumphs, from reading a book that changed your creative practice, to making a drawing you still like, to graduating college. Meditate on the perspective it brings you. Especially when feeling off, we tend to forget that no matter what, time will continue to pass, and we’ll continue to change and evolve.

In Spanish, like in other Latin languages, there are two different translations for the verb “to be”: ser and estar. While there are a few exceptions, “ser” usually refers to a state of being; a thing that is often permanent or unchangeable. Something you inherently are. For example, ser is used to say that you are a son, a sister, or an artist. “Estar,” on the other hand, refers to a temporary state, something that you are being. One would use estar to say “estoy triste,” which would mean one is being sad, without it implying that one is a sad person.

In understanding failure, as with happiness and sadness, considering the difference between a temporary state and an absolute one has always given me comfort. To be a failure is very different from experiencing failure. Acknowledge the temporality of mistakes and failures. It will give you perspective.

Also, call your grandma, or someone else who hasn’t heard from you in a while.

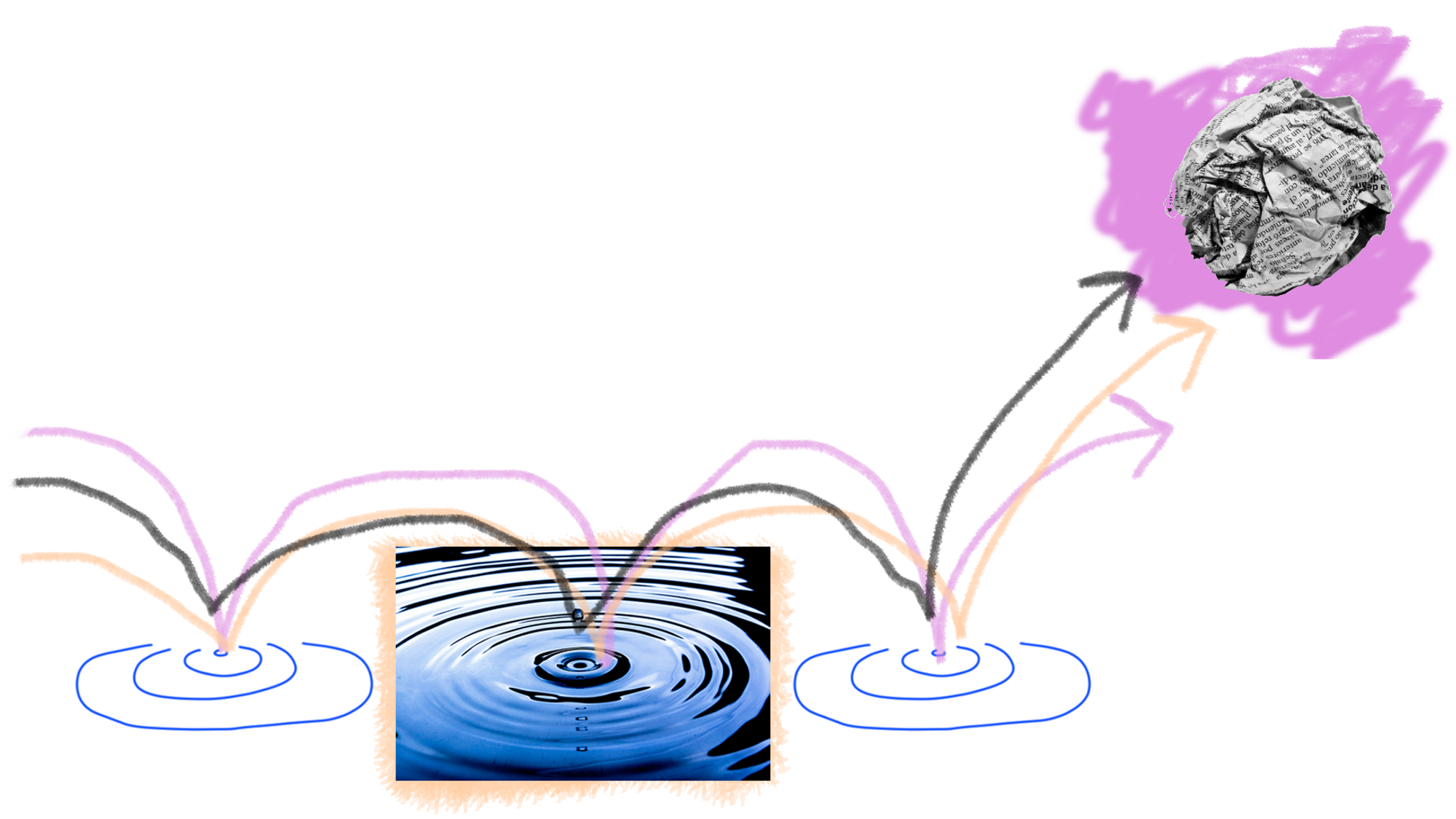

Tactic 2: Recycle past flops

Never underestimate the magic of slowness. Most things take time to find life. Spend some hours on your old computer, reopen your Hotmail or your 2012 Tumblr account. Ask your mom to send you pictures of your old notebooks. Reread the forgotten poems you wrote to your exes. At the very least, you will feel grateful you don’t use so many mirror metaphors anymore. Revisit a failed residency application, repurpose an undergrad research paper, or pitch a new version of a rejected story. Grab the things you once believed in and consider why they didn’t work: Were they truly bad? How could they have been better? Were you stubbornly trying to make an entire podcast series when what you had was great content for a single essay? Think about ways you could make something new, big or small, out of an old thing.

The pain of reentering something that didn’t work hides a joy of breathing new life into a forgotten project. Revisiting things can help us understand (or accept) something crucial we didn’t quite get in the first try. Practice, resilience, and a little bit of stubbornness are needed to get closer to what we want, or at least to what we are supposed to learn from it.

Also, drink water, and remember to breathe.

Tactic 3: Don’t stalk your nemesis

Failure is relative, and yet our idea of it is highly influenced by the perception of other people’s achievements—especially those who we consider (or once considered) our creative peers. To avoid falling into the trap of judging your own achievements against others’, honor your individuality at a microscopic level.

Here’s one way to do this: Write a detailed weekly list of small accomplishments. Here’s mine as an example/template:

-

Ate three apples, one with honey

-

Cleaned white shoes

-

Hugged a stranger who was crying

-

Put new batteries into the fire alarm

-

Said “no” to something boring

-

Advised people to read the forgotten poems they sent to their exes

In making your list, push the level of absurdity until it is clear that such accomplishments are unique to yourself. As you write, meditate on how the forces that influence and open up our creative paths are complex, and governed by many more things than merely how talented we are. Hard work, self-confidence, personality, social and economical privilege, beauty, education, language barriers, luck, health and mental issues, the terrible astrological sign we were born under, or being bad at the internet can all play a role in the way our professional and creative lives evolve.

Sometimes it can be a gift to ourselves to look at the beautiful sides of our own perceived disadvantages, or anything else that may stand in the way of us achieving our ambitions. Being bad at the internet is kind of endearing, and maybe it means you write beautiful postcards. Or ugly ones, but at least you write them, which is rare.

Also, read about intersectionality.

Tactic 4: Practice care

For years, Mark Zuckerberg’s motto was “move fast and break things.” This big statement of tech bros and entrepreneurial culture appeared on the walls of Facebook’s offices and was featured in the company’s IPO paperwork. The mantra was there to remind employers that creating new things fast was worthy of the mistakes in the process. And yes, acting without the fear of getting things wrong can boost creativity and help us take risks, but such a motto is not only irresponsible—it also shows a lack of interest in the consequences.

Zuckerberg’s mantra, especially popular among privileged folks, doesn’t pay attention to the waste of resources, or to giving space for the important knowledge that can come from carefully considering our errors. For us and for others, our mistakes have emotional, economical, social, and physical consequences.

To practice care, always try to visualize your mistakes/achievements timeline in terms of how it may have impacted the feelings and lives of others. Think about all the times you have rushed into something, and wonder if at any point your ambition may have harmed someone, including yourself. If you know you harmed someone by moving too quickly, apologize.

Take time to care for your own energy. Ask yourself what is the one thing you would put all your energy into if you could only pick a plan A. If faced with fewer options, we would probably make better choices. Before jumping into something new, meditate on your recent creative accomplishments and failures.

Also, get at least eight hours of sleep.

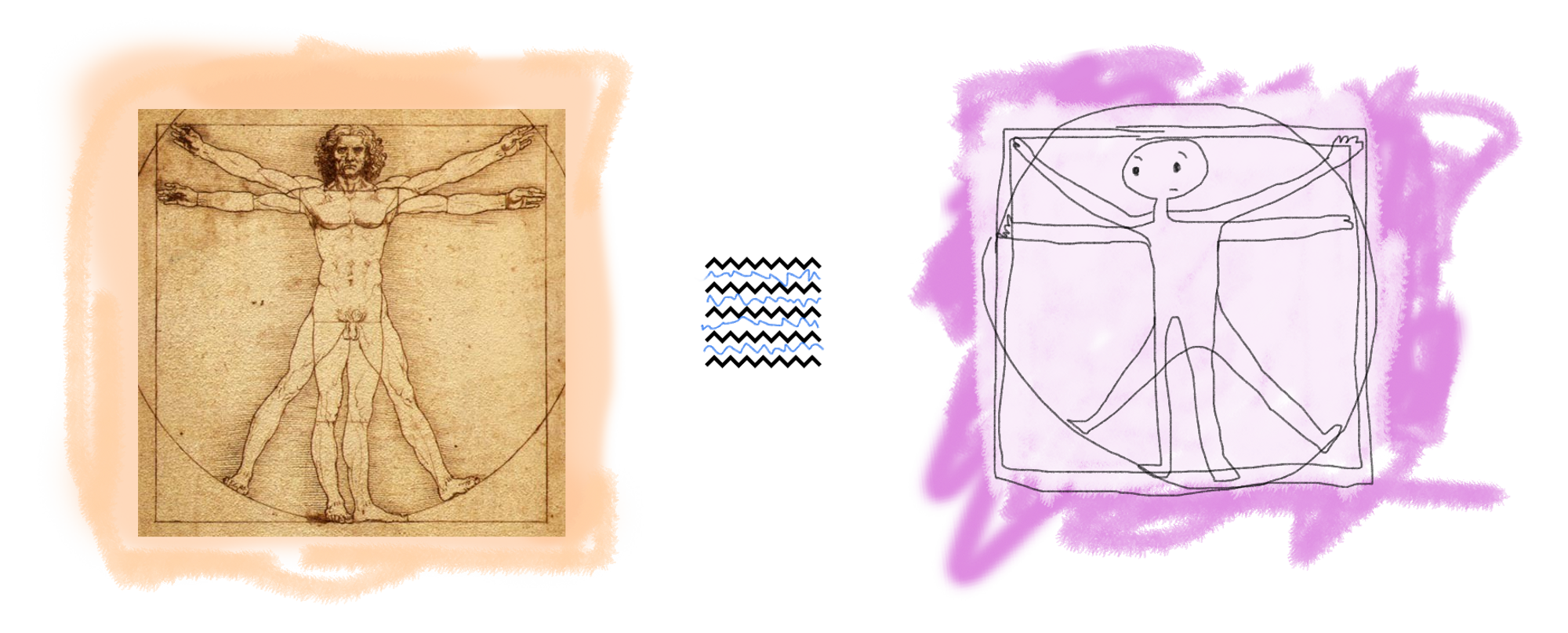

Tactic 5: Lock down your inner imposter

Don’t worry too much if you still don’t know what makes your heart sing. Don’t beat yourself up, privately or publicly. Impostor syndrome is real, but the self-deprecating artist is as sad as the overconfident fast-break-things entrepreneur. Let’s not glorify the tortured artist. Do the work. Try hard. Give things real shots, and if it makes you feel better, create a safe environment by labeling your attempts as “practice” or “an experiment.”

Do not punish those who win for your loss, and also don’t second guess yourself for your wins. Be ambitious, but also make sure to set accomplishable goals and slowly level up those standards before getting in over your head. Find things (grants, loves, residencies, jobs) worthy of real shots, and try very fucking hard to get them. Yes, if it doesn’t happen the frustration will be bigger, but if you picked the thing to aim for within the standards of the accomplishable and you put work into it, the chances of that frustration are smaller.

When good things happen, be happy for yourself. Own it. Meditate on why you deserve happiness, but never question whether or not you do. Even if you choose to believe an accomplishment was based on luck, take it. And if you do feel others deserve more, just share.

In the essay “A Praise to Difficulty,” philosopher Estanislao Zuleta highlights purpose and hard work, but also asks us not to settle for comfort. I remember reading it while trying to understand my desire for complex human relationships and projects that were neither too simple, nor a struggle. After years of confusing hard work plagued by guilt-inducing and unforgiving self-criticism, I learned that careful self-reflection is the only useful type of self-criticism.

In summary…

Getting some things wrong and comparing yourself to others is often unavoidable, but actively pursuing feeling like a failure for the safety it provides or for the sake of claiming experience in it, is not. Setbacks can be generative, and revisiting what didn’t work can make you understand better what does. Embrace and honor all your creative, seemingly senseless initiatives, and celebrate your individuality. You might not become a huge success, but if you have taken this guide to heart, you’ll know that’s not what matters.