How to lose someone

Introduction

Two years ago my father died. He was eighty-one and lived a long and good life. We had no traumas between us, nothing to hold on to anyway. He was a kind, sometimes stern, gregarious person who was born in a barn on an Iowa prairie at the end of the Great Depression. During his life he traveled the world, led many community organizations, and worked in countless different professions—from Catholic priest to real estate agent, gas station cashier to armored truck driver. He also taught me how to be a good person despite living in a world that often seems to only value selfishness, greed, and exploitation.

Before he passed, the last thing he said was, “Aw, that’s too bad, I’m sorry” in response to my mom saying their anniversary was the next day. After that he was in and out, sleeping, cringing, trying to find comfort in a body that was slowly shutting down. I put a “Green Grow the Lilacs” radio station on Spotify (his favorite version of the song, a rendition by Tex Ritter), and set my phone next to his pillow so he could listen to the music of gauzy nostalgia while we sat watch.

At 5:17 PM, a messenger for my dad’s second cousin and close friend, Sister Phyllis Anne (whose health was also failing, so she couldn’t make it to the hospital), came in. The messenger’s name was Sister Marie Kyle—both she and Phyllis Anne are Franciscan nuns. Marie Kyle came over to my dad’s bed and started praying that he would be able to let go. My hand clutched his left arm and the gospel song “Take my Hand, Precious Lord,” sung by Nashville-style crooner Jim Reeves, came on. As the song played, my father’s breathing slowed, and he seemed calm. His chest stopped heaving and by the end of the song, his body had turned white and waxy. It was 5:20 PM and he was no longer there.

**

Following my father’s death, I cried. I cried a lot. Not at his death bed—at that point, we (my mom, his brothers and sisters) felt relief. His death came slowly over four months: a hip surgery that refused to heal, complications from a pulmonary embolism which exacerbated an underlying condition, internal bleeding that darkened his back with deep blue swaths of loose, deoxygenated blood. Then came the wrapping of his failing body in a cloak of pain-killers and anti-anxiety medications during three long days of palliative care in the hospital. But for the next year or so after my father’s passing, the slightest thought about human connection would heave tears down my flushed cheeks. I had lost a connection that had been so constant in my life, so unquestionable, that once it had gone, I felt cut loose. Something foundational had suddenly vanished. I had lost someone.

My response to this loss varied from extreme to complacent. In the aftermath, I traveled for three months to visit dear friends (thank you for holding me during this time Thierry + Bruno, Andrea + Ben, Bernat + Andrea, and Genevieve), I quit a job that I had fallen out of love with, I moved cities so I didn’t have to grind incessantly while trying to mourn, and I took selfies of myself crying to try to see something I didn’t yet understand.

The following is a guide to how I experienced this loss. There is no right or wrong way to lose someone, but I do know that understanding their absence became the only way to know how much they were a part of me.

— Joel Kuennen

Step #1: Don’t just enjoy them or want them around, take them into your life.

To lose someone, you must first have them, you must love them. My dad was sentimental, uncool, kempt, and all too genuine. He reminisced to the point of escapism and was gregarious to an embarrassing degree. He loved people. He loved talking with them, hearing about their lives, understanding their stories. He listened deeply and offered counsel and a story in return. He was a day-dreamer, often drifting back from his internal life with the glint of a memory in his gray-blue eyes. When you grow up with someone, you read them incessantly. As I was an only child, the two people I read the most were my parents and given my predilection for quiet critique, I often sat back and watched, absorbing and then differentiating myself from these people who sat in front of me.

When I was older, I finally realized that the qualities I found irksome or dorky in my father were actually good qualities, qualities performed for my sake and his own. My concern for my ego and image as a teenager had dissipated (thankfully) and what was left was a deep appreciation for a person who tried hardest to do well by others. As I grew comfortable with myself, I no longer had to form my identity in opposition to this man who served as an authority figure in my formative years, and could accept him for who he was and enjoy the quirks and peculiarities that made him unique.

Step #2: Build your life around them. Be open to their input, to their influence. Trust them.

The day before my father died, he turned painfully in the hospital bed and said to me: “Remember when we had snowball fights across the driveway?” I grew up in central Wisconsin, back when snow fell thickly over the Midwest during long, cold winters. He and I would build snow forts on either side of the driveway, digging deep into the heavy piles, creating tunnels and turrets, thick walls and icy porticos. We’d then pile up snowballs for a few minutes and start flinging them across the driveway until our hands grew too cold and a truce was declared.

“One time, I snuck around the house and surprised you from behind. I’m really sorry I did that,” he said. I laughed and said it was “OK.” I remembered this pretty clearly, as I was around eight years old and was rightfully upset about the breach of our long-standing rules of engagement. I don’t remember holding on to any animosity afterwards, though, and was struck by the fact that it had weighed on him all these years. “Did something change after that? Did I treat you differently?” I asked. “No…” he elongated the “o” quizzically. “I just always felt bad about it.” The snowball fight represented a breach of trust in our relationship, and that had bothered him. It was a silly game and probably an apt lesson for the world, but he had felt he harmed the trust I had in him.

Step #3: Listen to them when they know they are dying.

Late one night, maybe a month before Dad would pass, he and I were sitting in the Lazy-Boys watching a baseball game muted on the TV. “I wonder how it will happen,” he said, breaking the stillness. “I will be walking to the bathroom and just fall over and die on the floor there,” he said pointing to the oak wood floor we had refinished when they bought the house after retiring. I didn’t know what to say and was silent for a few seconds.

“Don’t say that, not for a long time yet.” I reached out and grabbed his hand and held its papery skin in mine, squeezing it a few times before letting go. He smiled and we were quiet again, looking at the images on the TV. I regret not hearing more about that musing. I should have asked what he thought would happen when he died. I should have asked what he thought about dying in such a mundane but peaceful way. I should have asked what he thought about many things. If only I too could have faced the fact that our time was coming to a close.

Step #4: Be there.

I live a pretty itinerant life. Writing for a living makes stability pretty rare. However, I did have the freedom to go home during the time my father was sick: flying from New York to Wisconsin and back again, for a few weeks at a time. I came home for his surgery and left when he was on the mend. I came back when things started to decline and stayed until he seemed to be doing better. A week later, my mom called and said, “His time is coming.” I bought a ticket that day and was on a flight in the morning. He was in hospice after the embolism and we took him home after we noticed a large bruise crawl across his back. He was in good spirits, happy to be home, upset by the care people receive at the hospice. I agreed. A few days later he couldn’t catch his breath and he declared that he was dying. We called an ambulance. That was the last time he was home.

Step #5: Eat.

Once he was gone, we sat in the hospital room and his brothers and sisters shared memories. I sat there listening, less than four feet from his body. This is hard to describe, but he was gone. I looked at his body and he was no longer there. It is hard to not think of this in terms of some sort of cliché—like his soul had left his body—but that was what it was like. I understood clearly and definitively that the person I knew all my life was no longer inside this blanched collection of cells that had ceased functioning and had begun to undergo autolysis.

When an organism dies, its own existential inertia causes cells to continue to respire. The buildup of carbon dioxide, no longer carted away by a circulatory system, acidifies the cell causing the walls to rupture and the internal enzymes that break down fats, proteins, nucleic acids, etc. to flood out and begin to digest the organism from the inside out.

Later, I wrote in my journal, “We left his body in the hospital room. He was already gone. We went to eat.” I remember that meal being good. Satisfying. I remember the relief and the calm that had descended over the group as we ate fried fish and pickled beets. His impossible but inevitable pain was over and we needed to eat.

Step #6: Tell stories together.

The next day, family started arriving with casseroles in tow. Cousins, aunts, and uncles filled our living room. We found enough chairs in the closets and ancillary rooms to accommodate. That evening, thirty people were seated around the room, some on the oak wood floor. They told stories about him. How his two front teeth were knocked out in high school by a bad bounce of a baseball and he was fitted with a set of false teeth that he would later flip in and out of his mouth to scare his nieces and nephews into convulsions of laughter. He’d had implants by the time I was born, and this image of my father scaring my cousins made me cackle delightedly.

During one lull in the elogy my Aunt said, “You know, your father was a real feminist.” My mom blushed and again I thought about a dynamic I was inured to in a new way. My mom was the main breadwinner for the family, always having the most stable, high-paying job. She also managed to run the household—shopping for groceries, cooking, paying the bills—and I remember feeling that the share of work was unjustly split. But my father cared for me during those years. He was a stay-at-home dad during my childhood and a part-timer wherever he could find work—a role that I also saw as not traditionally masculine as I tried desperately to figure out what gender roles I was supposed to enact.

The family gathering after his death shed light on how others perceived him, and let me see him outside of being my Dad. All these people looked up to him. I began to see this man as Denis, as a brother, uncle, cousin, as a friend—all these other roles he had inhabited for many people throughout his life. This expansion of who he was unfolded before my eyes as others told their favorite stories about this man I thought I had known so completely.

Step #7: Take part in the way you need.

I’m not religious. A long time ago, I came to the conclusion that any social structure that purports to have The Truth will be used to marginalize and take advantage of others. But I was raised Catholic and both my parents were firmly embedded in the ritualistic and community-building aspects of the religion. They were social justice Catholics, socially liberal, accepting of scientific consensus, and believers in the moral code put forth by the Church—but still aware of the fallibility of human interpretation.

All this to say, my Dad took me camping a lot. Back when my Dad was a priest, part of a generation of priests who ultimately became disenchanted by the refusal of the church to liberalize during Vatican II, he purchased a plot of land in Northeastern Iowa. It had a limestone bluff overlooking the wandering North Fork Maquoketa River dotted with fragrant eastern cedar trees that were gnarled like large bonsais by winds from the west. We’d camp along the spine of this bluff, starting campfires with dead cedar twigs and felled trees that we cut into logs, letting the teeth of the saw “do all the work.”

The smell of this burning cedar, its majestically piquant incense, will always remind me of him and those days roaming this wild land, turning over bleached porcine bones and fossilized coral, biting the sweet polyps off Columbine flowers, and roasting hotdogs over the fire. I went to this land the day after he mused from the Lazy-Boy about how he would die, as a kind of pilgrimage back to this place of childhood. He was supposed to come with me but wasn’t feeling well, and had insisted I go on without him.

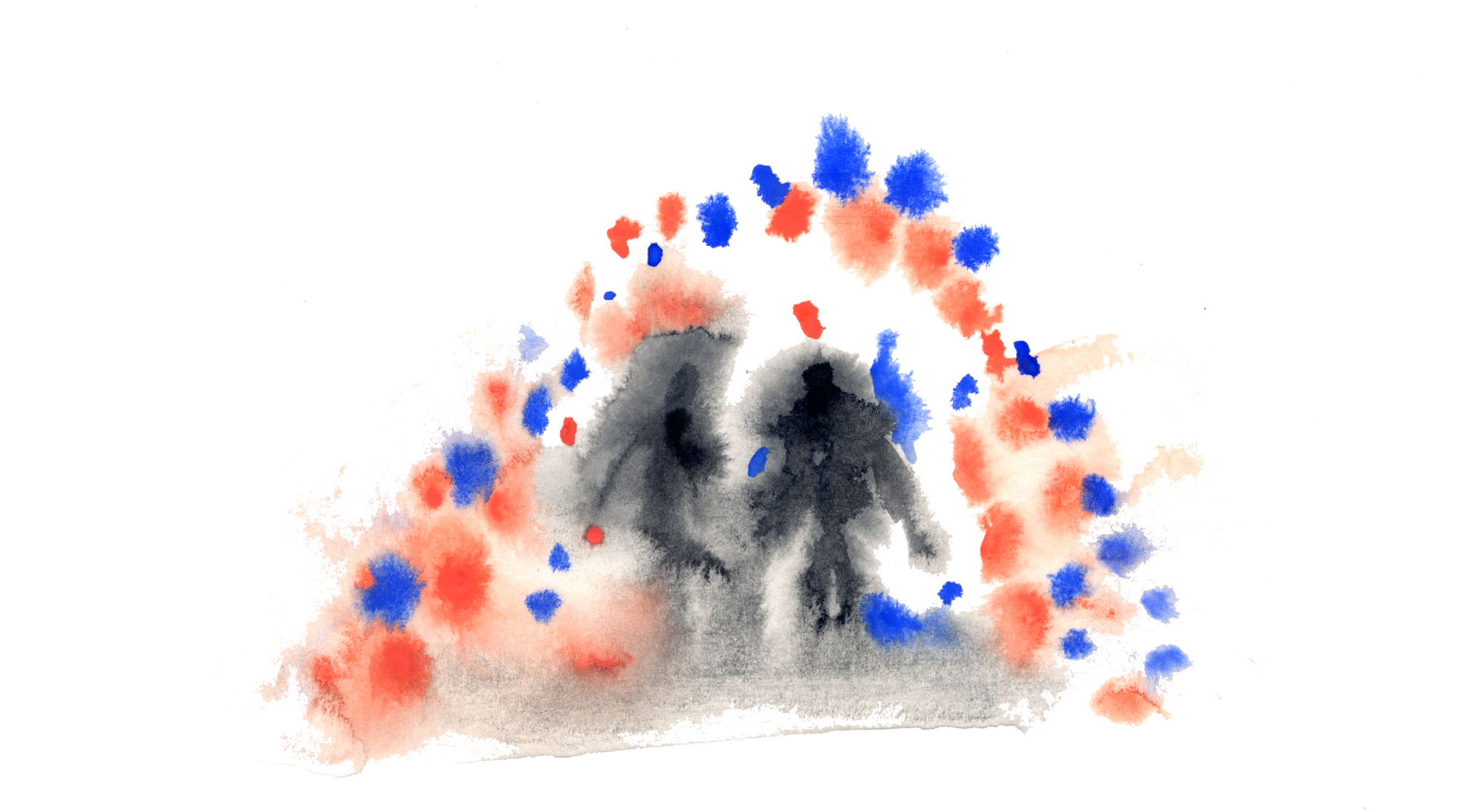

On the ride down was the first time it dawned on me that he was going to die. He never turned down a trip to the land before. Tears erupted and a deep sigh shuddered my chest as I drove down the highway that hugged the Mississippi River. His life would empty into the sea just like this endlessly flowing river, breaking the bounds of his personhood and dispersing back into the primordial ocean. I took a selfie: the first selfie in a series of some eighty-plus images I would take as I mourned him.

I only stayed one night, setting up camp, lighting a fire and putting a cast iron pot of potatoes, onions, carrots, and beef to simmer over the coals. I gathered some of the cedar to take home with me. That night, I spent hours carving a slim wisp of a cross from the cream and crimson wood. This cross adorned his coffin for the funeral.

Step #8: Don’t lose them, remember them.

On the grave of postmodern psychotherapist and theorist Felix Guattari, there is a plaque given by Le Club de La Borde, the association of the psychiatric clinic he worked at for the majority of his life, that reads: “There is no lack in absence. Absence is a presence in me.”

The sheer weight of my dad’s absence hung low in me for months following his passing. There wasn’t a day I didn’t think of him and feel completely dissolved that this man I had known my entire life, this man who had felt so bad about a snowball fight for all these years, was never going to hug me, chide me for leaving a light on, tell a bright-eyed story about his past around a fire, or tell me he loved me, again. This lack of possibility, this lack of presence—even at a distance—was unbearable. A deep emptiness would yawn inside me, pushing tears up from my neck to squeeze out of tight eyes and in those moments I would take a picture. The only thing that made sense to me in those periods of existential disarray was to capture each moment I fell apart. What I realized later was that by taking a photo of myself crying, I was trying to document the presence of absence. I was trying to see him still present, even in the anguish of his loss.