How to work within power structures that don't work for you

Introduction

I used to want to live the artist’s life. I imagined this meant being unfettered by a 9-5 job and spending my days in my studio and my nights meeting friends at gallery openings. This is a naïve but common image of The Artist. I imagine if you’re reading this you already know it is a fantasy.

The reality of the artist’s life is less romantic. Creating art is work. Attending shows, doing studio visits, and sending emails that multiply like hydras is work. The spreadsheets of deadlines, proliferation of to-do lists, and the constant need for up-to-date images is work. Even this article that sat in the back of my mind as the guilt piled up for a week past my self-imposed deadline is work.

And not just work, but work that is largely unpaid or underpaid. Most artists are not able to support themselves from their art alone. There is no artist 401K or healthcare plan. And if we were to add up the hours spent on everything listed above, the hourly wage would be minimal. We’re told that it is okay that jobs like making art, or teaching, or care work are low-paid because those lost wages are made up for by a sense of passion and personal fulfillment. But being passionate about your work, whatever you do, is not an invitation for exploitation.

In short, using passion and fulfillment as excuses to justify low wages is nonsense. And for artists, all it means is that we become a cheap supply of labor for museums, galleries, art schools, and the art market and creative professions more generally.

So what is an artist in a capitalist system to do?

I’m an artist. I’m also other things—an activist, a tech worker, and a parent. I haven’t figured out the answer to the question I posed, but I’m sharing this guide to offer another perspective on working as an artist under capitalism.

I won’t pretend to have answers. Instead I’ll offer a challenge: work within these systems, but refuse to internalize the norms of racial capitalism.

To do this, let’s begin by exposing the myths of the artist’s life that we all must move on from.

— ann haeyoung, artist, activist, and tech worker

Step 1. Recognize that we can’t all be in the 1%

The system of racial capitalism we live under favors the success of a tiny minority at the expense of the majority. In the art world, this means that a few artists accrue the bulk of the invitations to show at major institutions and the bulk of profits from sales. Yet most artists aren’t able to make a living from their art work alone. And even those whose work gains widespread recognition—who win grants and awards and receive invitations to lecture and speak—may never escape financial precarity, as the very nature of the system means we can never be sure if another grant or sale is in our future. There is no artist’s pension. There is no employment contract.

We are told this system is a meritocracy, where the most talented and hardworking people are granted entrance to the top 1% of earners, but this is far from the truth. In reality, those with wealth and privilege are able to stay at the top through access to networks of capital, while the majority of people—regardless of how hard they work—remain at the bottom.

I don’t say this to be demoralizing. Rather, realizing that we can’t all be in the 1% is empowering. It allows us to see the broken system for what it is, to reframe ideas of success and failure and our relationships to one another and our own creativity, and to create alternative systems of power that reject inequality.

Of course, while we’re building those alternative worlds, we still need to deal with the reality of surviving within the system we have today.

Step 2. Set your intention (and reject the ethos of the side hustle)

I fell in love with art when I took my first drawing class at age eight. My art career began with a meticulously copied mouse from If You Give A Mouse A Cookie, and eventually progressed in my teens and 20s to charcoal and painted portraits.

Once I began working full-time, I struggled to continue making art in my off hours. I bought a giant canvas that I leaned up against the wall across from my bed in hopes it would guilt me into making work. It sat as a half-finished painting for a year, more a reminder of my diminished free time than a call to artistic action. I felt disheartened using my nights and weekends for work that felt unproductive. Making art was neither moving me towards financial independence nor was it giving me much pleasure. At the same time, I felt bored out of my mind at my job.

I thought the only option for me was to find a way to combine creativity and earning money. At work, I tried moving towards more “creative” roles, inching closer to strategy and design. After work, I tested out a string of creative projects that I thought were monetizable—bike gloves, greeting cards, throw pillows—and went so far as to apply for graduate school for creative entrepreneurship. (I ended up balking at the price tag and my own ambivalence towards the program’s goals.)

It wasn’t until I stopped trying to combine art and money that I started enjoying making creative work again. I made my first useless object, a battery powered by blood, and it was fun. I realized the things I liked to make defied easy commercial categorization, and that was okay.

While all artists who have day jobs have to make art “on the side,” the key difference between making art on the side and the side hustle is intention. For artists who want to keep making work that is not commercially viable, letting go of the profit motive means we can let go of the pressure to sell, to cultivate our “personal brand,” and to constantly grow our audience. We can simply be artists instead of trying to also be entrepreneurs.

If you’re not familiar with the idea of the side hustle, Damon Brown defines it as “not a part-time job. A side hustle is not the gig economy. It is an asset that works for you.” The side hustle is a path to financial independence. It is my throw pillow or greeting card business. It is a promise that one day, the creative work you are doing will set you free from drudgery. It is the phrase of the day to describe the age-old American myth of the self-made man.

When applied to art making, the premise of the side hustle is that it is not productive to make art if it is not in the service of profit. The idea of the side hustle frames an inability to make money off your art as a personal failure, and glorifies art that is “commercially viable” (aka art that appeals to those with wealth). This is a particularly destructive myth for artists from marginalized groups who make work that is valuable to their own communities, but not to the majority of gatekeepers with the power to decide what is “commercially viable.”

Setting an anti-capitalist intention with your artistic practice doesn’t negate the need to earn income. The good news is that there are lots of ways to make money as an artist besides turning your artistic practice into a side hustle.

Step 3. Create new definitions of the artist’s life

“Artist” isn’t a title limited to those with a particular type of job or lifestyle. And it certainly has little to do with institutional or financial legitimacy (i.e. having gallery representation).

You can be an artist with a 9-5 job. You can be an artist with one, two, or a myriad of part-time jobs.

Each person’s needs are different. You know best what your needs are. Are you supporting family? Do you have particular healthcare needs? What options for wage work are available to you that fulfill those needs?

The options for artists who aren’t making money from their art can feel limited. I often hear advice to artists who need to earn money that falls into roughly two categories:

- Do work that gives you flexibility (i.e. freelance work)

- Do work that keeps you in the art world and/or using your skills. That could mean doing commercial photography if you’re a photographer, or it could mean teaching art, doing art handling, or working at a museum/gallery.

The above two options are definitely ways to make a living as an artist, but they are not the only ways. I rarely hear artists being advised to do work that has nothing to do with their art, for example. But why not?

Let’s start by taking a critical look at the two art-related options above, just as we did with the side-hustle option. What narrative are they supporting?

Firstly, the options above assume you have the ability to choose your job and organize your work and time in the way you see fit. Many people face structural barriers that prevent them from being freelancers or finding well or even adequately compensated jobs in art-adjacent fields.

Secondly, both options—like the side hustle—assume that working in the arts or creative industries is the only desirable way to Be An Artist™. However, by conflating passion and work, we are more likely to act in ways that may undermine our own interests as workers. Because we are passionate about the work, we end up staying late for unpaid overtime, taking on additional emotional labor, or paying for art supplies for a job out of our own pockets.

And the surplus of desperate workers willing to accept lower wages or poor working conditions because we’re told it will get us a foot in the door to the art world means we all suffer. Employers continue to lower wages and take away benefits, knowing they will still find workers to take the jobs on offer.

We see this in the high cost of art school and unfunded (or costly) residency programs, or pay-to-submit art shows, not to mention the low-wage and physically difficult work of many art-adjacent jobs like museum security guards, who are forced to stand for hours on end, or teachers, who spend time and energy helping students outside of class.

Artists are asked to give everything for a dream.

I’ve been there. I’ve been told that that’s just what one has to do. I’ve paid the residency and submission fees. And I’ve come to realize that this only feeds the beast. By capitulating to an extractive system, our actions harm all artists, because these behaviors promote a system where artists without financial means cannot participate.

I don’t blame the artists—the ones who go into debt for art school or pay a fee to have their first residency or show on their CV. We are simply trying to figure out how to survive, and have few models for success.

So I’d like to offer a third option:

Take the job that has nothing to do with your art or your passion, and take it unapologetically.

It is not a personal failing if you want to (or have to) take a job unrelated to art, especially if it fulfills a need like paying the bills or providing healthcare.

And for those artists who want to (or have to) remain in art-adjacent or freelance jobs, fight back against exploitation by sharing promiscuously. Share your rates if you’re a freelancer. Share your wages if you’re an employee. Call out your unpaid or underpaid labor. Talk to your co-workers, organize, and refuse to play the game of self-exploitation.

If you’re wondering what this looks like, I’m inspired by art workers at the MoMA demanding fair wages, and at the Whitney speaking out against unethical business practices. I’m inspired by artists like Taeyoon Choi, Morehshin Allahyari, Everest Pipkin, and Caroline Woolard and the many contributors to the art worker salary transparency project who give openly and generously and who lift up fellow artists.

Step 4. Living the 9-5 artist’s life

For me, working a 9-5 job totally unrelated to my art fit my needs. This is not to say I will do this type of work indefinitely, but it is what I want to do for now. My role as a full-time project manager means I don’t need to worry about where my next paycheck is coming from, and I can make the art I want to make.

Separating my art from my main source of income made sense. Granted, there are issues with this path.⁕ More than the lack of flexibility or soul-crushing-ness of full-time work (often cited as the reasons to escape a 9-5), the hardest part for me is feeling isolated artistically. Working outside the art world, I have to do extra work to find a community of artists to share with, talk to, and learn from.

Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to engage my coworkers in conversations about my art. When we do discuss it our conversations never progress beyond the odd comment. For the most part, my coworkers are disinterested. Some are dismissive or condescending.

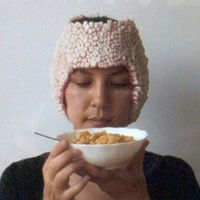

Perhaps because of these dual-personas I end up straddling, I’ve found my wage work creeping into my art—not in the tasks asked of me, but in the artwork I make. Before I started bringing my experiences at work into my art, I treated everything I was doing outside of work as my “real life,” and my 9-5 work as a necessary nuisance. I felt mentally and emotionally drained after work and frustrated that I wasn’t able to spend more time on art. In my practice, I was making work about identity, but completely ignoring my identity as a worker. I’ve since realized that work vs. self is an arbitrary distinction. I spend a huge percentage of my time at work, and it is impossible for that not to affect how I see the world.

My job in the tech sector has given me a different perspective on labor and technology, and the work I do and the people I meet in my day job find their way into my art. While at work, I am also exposed to the latest challenges facing the tech industry and tech workers, and this unique insight gives my artistic critique a depth I may not have had otherwise. I am more alert at work, noticing a turn of phrase, an object, an interaction between colleagues that I might have ignored before. Everything is available to be filed away for further exploration in my art.

This is not to say I’ve come full circle and am combining my wage work and my creative work. Instead, I am using my identity as a tech worker as inspiration for my art. In one recent video, I looked at the relationship between a fictitious tech worker and the technology they were creating. In another, I explored my alienation from my own labor as a white collar worker and from my fellow tech workers across the industry. And just last week, I began a project looking at office plants, their relationship to the history of colonialism, and the over-the-top office jungles preferred by tech companies.

Being an artist has led me to critically engage with my identity under capitalism. And through this engagement, I’ve also found grassroots and worker-led organizing, which has brought new relationships and new forms of activism to my life.

It is important to recognize your limits and know when to step away. For me, I feel best when spending time with people I love, when making and sharing new work, and when I feel that what I am doing aligns with my values. So I try to work on collaborative projects, I use art as a way to start conversations and friendships, I organize with people I trust and enjoy being around, and I try my best to be honest about my values in all aspects of my life and to stay open while continuing to learn.

⁕ A note on burnout: holding down a job or jobs while making art and still keeping space for friends and family is difficult. Going to a job every day that you do not enjoy is draining. Suffering under systems of oppression is exhausting. It is important to name these issues and to look at what makes being an artist so hard (under-compensated labor, no universal healthcare, racism, sexism, and other barriers) and to recognize that all too often, passion is used as an excuse for exploitation.

Step 5. Art, work, and organizing

There are numerous amazing people and organizations fighting for worker and artist rights. These are a few that I am learning from and inspired by every day: Working Artists and the Greater Economy, Decolonize This Place, No New Jails, and my fellow workers in the Asian Diaspora in Tech discussion group. While organizing is work too, I have found that it helps me battle feelings of isolation and hopelessness. Instead of only surviving within the system, organizing has helped me to thrive within it.

I have found my voice in the workplace, speaking out against the problems I see and speaking up for myself and others. From calling out microaggressions to arguing against doing business with ICE, the daily practice of speaking out can be just as meaningful as the larger campaigns.

I also have found my voice in the tech industry, organizing against unethical business practices. We are campaigning against companies building tech for ICE, pressuring employers to change unfair and opaque wage practices, and building solidarity within the industry and with organizations and people across industries and causes since our goals are all connected.

Lastly, I have found my voice as an artist, discovering the world I want to build and finding others to build it with.

In summary…

For me, it was empowering to realize I wasn’t going to beat the odds and make it as a “full-time” artist. I stopped spending my time and energy wondering how to combine my wage work and my art. I stopped feeling like I was constantly falling short, and that every second spent doing anything but furthering my goal of profiting from my art was wasted. Instead, I went for a 9-5 that let me make the art I wanted to make in order to spark the conversations I wanted to have.

As you navigate the balance between working under racial capitalism and making art, ask yourself: What is it that drives you to want to make art? If it is wealth or fame, then I have nothing for you. But if it is anything else, then I encourage you not to undermine our shared interest as art workers by normalizing exploitation as part of the artist’s life. I encourage you to share, to build relationships, to organize, and to lift one another up.

Let’s think together of other possibilities for artists. What other ways can we define success? How can we normalize a more generous definition of who gets to be an artist, and who gets to be creative?

Finally, if any of this resonates with you, feel free to reach out. Connecting with each other and having conversations is how we build new and different worlds.