On turning up marginalized voices with activist art

Prelude

Amplifier is a non-profit design lab dedicated to amplifying the voices of social change movements through contemporary art and community engagement. Their experiments are built on a foundation of free and open-source art, human-centered design processes, and the merging of analog and digital technology. They’ve run two campaigns on Kickstarter—one to distribute public protest art at Trump’s inauguration and another to feature diverse historical leaders in classrooms.

This conversation is part of our Signs of Change series highlighting creators who have previously launched activist posters, broadsides, stickers, and zines on Kickstarter and encouraging newcomers to participate in Kickstarter’s open call for projects.

Conversation

On turning up marginalized voices with activist art

Amplifier’s Cleo Barnett and Aaron Huey on making positive propaganda, collaborating with communities, turning artists into activists, and engaging authentically.

As told to Katheryn Thayer, 3143 words.

Tags: Art, Design, Culture, Activism, Education, Mentorship, Politics, Process.

Where do you see Amplifier relative to the long history of print ephemera shaping political conversations?

Aaron Huey: I think the origins of Amplifier and some of the first artists we started with, like Ernesto Yerena [Montejano] or Shepard Fairey or Jessica Sabogal, they really speak to that history of print ephemera, that tradition of strong, almost propaganda-like graphics—and Shepard would use that word, propaganda, for it.

In history we’ve seen propaganda as inherently slanted and used incredibly negatively, but some of the artists we work with look at their style as almost in that same vein of propaganda, but slanted to the good. At Amplifier we are trying to make that imagery that slants to the good: positive imagery and messages that move us forward and can act as the compass pointing to a future we want to live in.

When I look at contemporary print ephemera, we’ve probably distributed more than anyone in U.S. history—four or five million physical objects over the last few years, and we consider that analog element a critical part of this work. We always have a dual strategy with digital and print, but the print is absolutely crucial.

How do you want to push the tradition forward?

AH: I think that we push the tradition forward by broadening the range of styles. While we may have started with a lot of that work that looks like Ernesto’s or Shepard’s, the range of styles has now broadened incredibly, the diversity of voices, and then of course the distribution methods. I think those are the three channels that we just keep pushing and pushing and pushing. And that’s why it keeps changing shape and evolving.

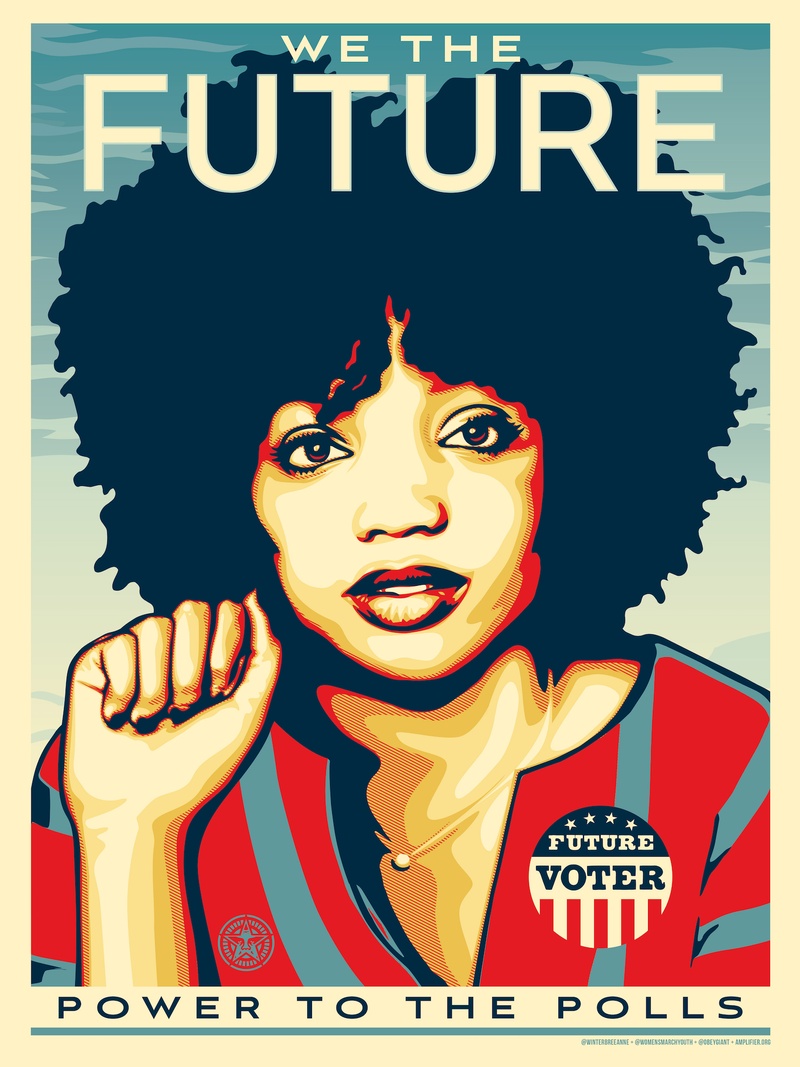

Shepard Fairey, Winter BreeAnne, We The Future

The artists seem so much more front and center than the more traditional propaganda that you mentioned. Is that part of your strategy?

Cleo Barnett: I think a big part of what we do is providing people with tools to become more active citizens. Part of that is flipping artists into activists. We’ll work with our community partners and artists to co-create the creative brief for the artworks, which is a process that a lot of artists and partner organizations haven’t been part of before, but after working on an Amplifier campaign and being embedded into our process of centering the voices of people most directly impacted by issue areas in the design and creation of our art campaigns, organizations learn how to weave artwork into their work and artists never want to go back to just regular commercial work.

Take us through, beginning to end, what the process tends to look like.

CB: It normally starts with a community that wants to be amplified. We work with that community to understand their target audience, what they want their audience to do, and then oftentimes we’ll do a series of design sessions or language labs in order to collaborate with those communities to create the framework of the artwork commission itself. Then from there, we’ll look at who we all think will be the most effective artist to bring into this process and bring these visuals to life. Oftentimes it’s a mixture of emerging and well-known artists, artists who are directly impacted by an issue area, and artists who have a specific technique we feel will be powerful for achieving our campaign goals.

Alongside commissioning the artwork, we’re also thinking through how to get this artwork into the hands of as many people as possible, specifically the target audiences, and that’s where the distribution tactics come into play. We have a loose framework, but we hope to approach every campaign with a fresh perspective and a custom design strategy. It’s our distribution techniques and human-centered design approach to campaigns that feeds into an ever-evolving approach to media experiments and allows us to do our work, including rapid response campaigns, in a way that allows us to reach new audiences in a way that is authentic to the communities we are collaborating with.

Does the process always go smoothly?

AH: Once an artist gets a brief, it does really vary quite a bit. An artist might send something in that’s an absolute home run, that’s it. And sometimes we may go through six rounds of edits where our creative team really works with that artist helping narrow down the message with the organization that we’re trying to amplify. It’s as varied as the artists that we work with.

For some of the more subtle and nuanced design details like the layout or the fonts, is that something that you’re giving direction on or is that coming from the artist?

CB: It’s very collaborative between the movement, the community that the artwork’s representing, the artists, and us. First and foremost, we want this artwork to be very clear and easy to understand from a distance and easy to understand very quickly. Oftentimes there’ll be one core piece of language that’s really clearly laid out. It invites the viewer in. Maybe they just think it’s really beautiful. Maybe they’re captivated by the image or the language. And the hope is that once it invites viewers in, then there’s layers of understanding and interpretation the more you look at artwork.

AH: There is no formula, but really simple is always best. I often tell people we’ve done workshops with to keep it to three to seven words. It should be something you can really see out of the side of your eye, walking down the street, that literally stops you in the street. If it doesn’t stop you, it didn’t work. You’ve got to be able to read it, visually read it, in a fraction of a second.

CB: I normally suggest sticking to two to three colors when you’re first starting out. Then think through the symbology. What is the imagery that goes with the words? There’s a lot of opportunity there to layer in symbolism. Maybe not everyone will understand, but it will really be meaningful to the people who do.

Your process of being really in touch with the community seems to help you avoid what I’ve heard called “creative savior complex”—sort of like white savior complex, we’re seeing so many white artists rushing in to paint portraits of George Floyd, and it’s not always the best tone or best allyship. What’s your advice for artists who want to be part of the cause right now, but don’t want to fall into that danger zone of doing it inappropriately?

CB: You should really go to the movement leaders who have been doing this work for generations and look at the language that they’re using and that they’re wanting to uplift, or get in touch with them directly and see how you can support their work. At Amplifier, we really position ourselves as back-end support to front-end movement leaders.

I mean, this is a great thing about the internet—we have access to so much information. So for instance, when the Black Lives Matter movement has been arising over the last few weeks, straight away I knew who the leaders were in our region. In Seattle, I was looking to Nikkita Oliver, who’s been doing this work for generations. And in Los Angeles, I was looking to Patrisse Cullors. Going directly to the source is really smart because there are a lot of organizations and people, unfortunately, who co-opt these movements in these times to profit off of them and to move their own agendas forward. I think just take a step back and instead of doing this knee-jerk reaction, take some time to do a bit of research and educate yourself.

Another big thing, especially for white artists, is just being conscious of how you’re positioning yourself within the work. For instance, we’re commissioning a series of artworks right now from Black artists and we’ve had tons of white artists reach out to us. And the only one we’re working with is one who actually said that he would donate his services, he would not even want to put his name on the artwork, and that we could use that extra funding to support and uplift Black artists. That was a really authentic way to engage right now. What we’re seeing is the potential for white artists to create work, and then even if they don’t mean to, that work could then go viral, re-centering themselves at a moment when it’s not really about centering white voices. So just being conscious of the space that you’re taking up.

On the other side of your process, the distribution, I’m curious what you think about print posters’ place in this very saturated media diet. My Instagram is full of protest pictures. Why is the printed material so important? And what special impact does that have?

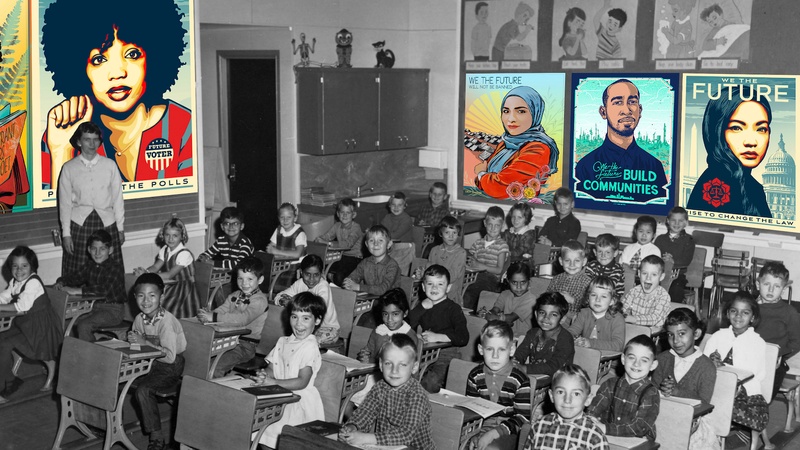

AH: Print has so much more power than digital distribution, even when the numbers on digital are much greater. Take our classrooms as an example. We have 20,000 teachers who have this work, and it is not something that is getting swiped away. It is going to be there for two years or five years or 10 years, for all we know. And that art continues to broadcast all day long to that entire classroom, where it’s so present that it becomes subconscious and super saturating. When those kids grow up, they are going to remember those images and messages from their childhood. They will not remember many of the things that they swiped by.

And now, one of the ways that we’re going to be evolving is that we see the potential to turn all of those physical objects into a new call for action with augmented reality. We’ve begun to build prototypes and samples for how printed Amplifier art can come to life into a three-dimensional living form through our cell phones or iPads or any camera-based device, turning what you see in a newspaper or on a classroom wall into something that can literally speak to you. That young leader in the image can talk to you about the future that they imagine, or they can talk to you about how to get involved with civic engagement in your community.

This is my personal obsession right now, because I’m always thinking about media evolution and new media and how Amplifier as a whole can make pieces come to life and have more of a call to action than the three to seven words on the front.

Amplifier in the Classroom

When you launched, did you feel like you were putting the print first more, or do you feel like you’ve always been looking for these creative ways to bring in new media with the traditional print posters?

AH: The origins of this project were straight-up wheat pasting and stickers. It was really like stealing space. I don’t feel like I need to mince words around that. The goals originally were to steal back the ad space. This was tens of thousands of wheat-paste images and stickers on street signs in a dozen cities.

Was there a strong digital promotion element back in that original project?

AH: There’s always been a way to link to the resources of the people on the ground doing the work. There’s always been a way to get the art. There’s always been a way to learn more. And there’s always been a way to download the work for free so that it can be spread wherever the community wants it to go. Originally those free downloads, the concept was, to be honest, it was plausible deniability, because whether we put up the work or somebody else put up the work, we couldn’t necessarily always control what buildings got pasted, and the work needed to be available so that we could kind of have clean hands—we knew we were not going to totally get permission.

Did you ever get into some legal tiffs you had to use that plausible deniability on?

AH: No. With our downloads we’ve always said, “These are yours to use for noncommercial purposes. Just be aware of laws in your community. Good luck.”

Is there any other guidance you have for protesters? I mean also right now with COVID going on, are you trying to be a beacon of good examples and letting your community know how to protest safely?

AH: Yeah.

CB: I mean, I think there’s so many different ways to take action. That’s the biggest thing. And for us, we’re just amplifying social movements. That’s our main way of contributing to this moment, uplifting and supporting the leadership of Black voices.

One way that we’re supporting, for instance, here in Seattle is we have this CHAZ, [Capitol Hill] Autonomous Zone, that’s being developed in real time. And a big issue that we keep hearing is that people don’t know the core demands of Black Lives Matter. Random protesters will get interviewed by press or will be talking to one another and a question will come up like, “Why are you here, why are you protesting?” And people don’t actually have an answer, which can be really destructive to the movement. What we’ve done is we’ve collaborated with a local organization in Seattle to give them access to our artwork and they’re actually doing live screen printing down on the site. The demands from Black Lives Matter are on one side of the print and our artwork’s on the other side. People are drawn in because they want a piece of artwork, but then the demands from Black Lives Matter are on the back. Our main focus is supporting the movements themselves.

Amplifier in Protest

From what you’re seeing happening in the world right now—with COVID, with Black Lives Matter—what do you want to see artists doing more of? What do you think are some of the positive trends that you would like to see amplified?

In the wake of both of these current crises and movements and whatever is to come, we have to continue to imagine. No matter what new emergencies pile on, we need to be constantly putting out that vision of the world that we want to live in, the world where we talk about taking care of ourselves and protecting each other. There are so many messages that will transcend each of these individual moments, but that acts as an umbrella over all of them. And I think that there’s a lot of language around the pandemic as a portal—what do we want the world to look like on the other side of this? We could be asking that question all the time. We’re always trying to look through that portal. And I think all of this art represents that. This art is pointing to the other side of the portal, to the world that we want to live in.

CB: And something for Amplifier, Amplifier doesn’t necessarily make artwork that showcases what’s wrong. We showcase the direction we want to head in. So very specifically for artists, we don’t want to perpetuate images that negatively portray people. We really want to showcase what could be.

So you would you be much less interested in the ACAB posters and much more about a Black Trans Lives Matter poster?

CB: Yeah. And also when you say defunding the police, okay, that’s really powerful. But what does that actually look like? What does community investment look like? What does it look like for people to have access to clean water and healthy food and mental health support and access to education, access to housing. Can we actually paint pictures of what that looks like and put it out into the world to help transform the radical imagination of our culture at large?

AH: We’ve had this discussion internally. We’re not going to put out images of burning cop cars. Those are very popular right now on the social medias. We can put out imagery of a police car turning into flowers and becoming something that is like a new future, but we cannot put out imagery that incites violence in any way.

But at the same time, do you want to be careful not to do some of the really surface-level feel-good imagery like the cops hugging protestors?

CB: Yeah, totally. And I think the beauty is that we’re all contributing in different ways. Amplifier’s just one piece of a larger movement right now. And so we’re really clear on what we do and what we don’t do. And I think some of those other images are powerful. I mean, what we’ve seen in the last two weeks with people protesting has arguably created a larger societal shift than our past election had.

What I would say to artists, especially new artists that are getting to this work for the first time, is I would say your voice really matters. If you have a hundred followers or if you have a hundred thousand followers, you are a leader in your community. What you put out into the internet and into public space does resonate and impact the future of the world.

But take some time to do some research, and make sure you’re not just recycling what you’re seeing online—take all the information to create an original thought with it.

Would you also encourage them to try doing something physical instead of just the digital images that we’re going to scroll through and forget?

Not only does physical art continue to share that message over and over again in your classroom or home or whatever, when you have a physical piece of artwork it meets the viewer where they are. When you’re having a one-on-one conversation, it’s so easy to get defensive or shut someone out or create blockages. But when you’re just an individual and you come across an artwork, the artwork meets you where you are and has a personal dialogue with each viewer. And I think that’s something really, really powerful about public art.

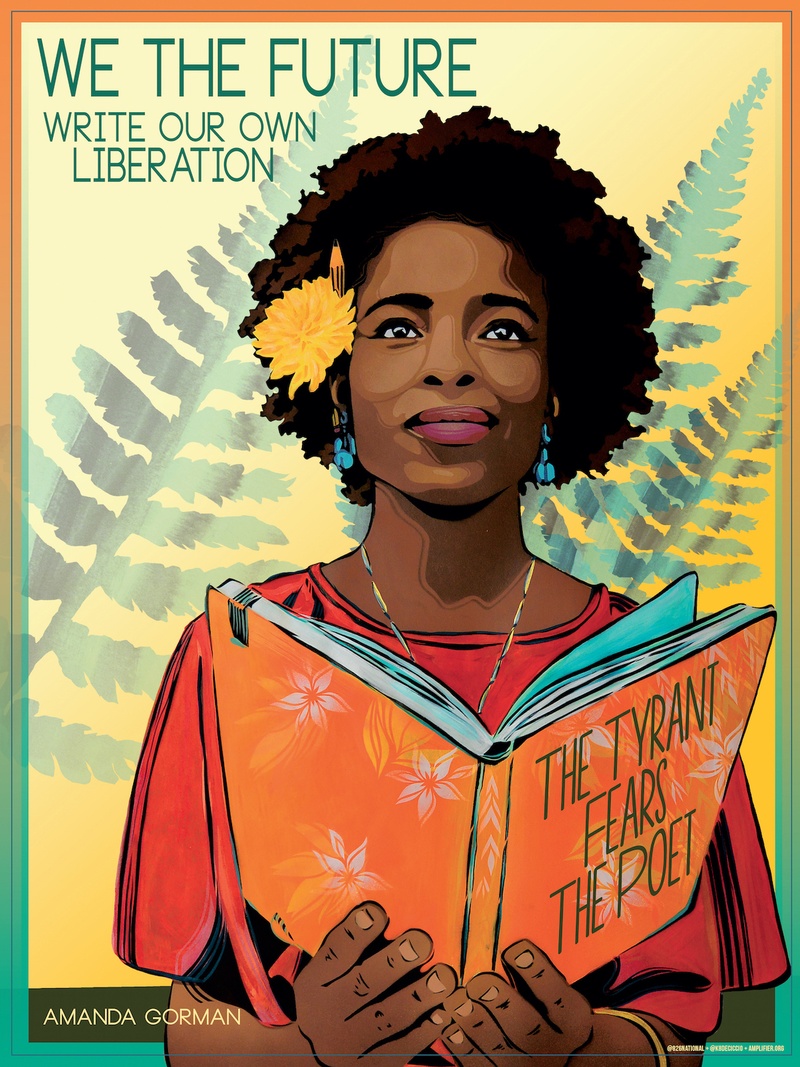

Kate DeCiccio, Amanda Gorman, We The Future

Five inspirations for Amplifier’s work:

-

All the artists who are brave enough to make work and install it out in the world without permission to reclaim space!

- Name

- Amplifier’s Cleo Barnett and Aaron Huey

- Vocation

- Designers and educators

Some Things

Pagination