On the power and possibility of criticism

Prelude

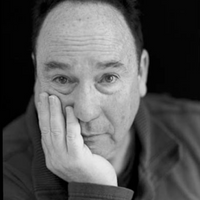

Lori Waxman has been writing about contemporary art for nearly 20 years. Most notably, she’s been the Chicago Tribune’s primary contributing art critic for over a decade. She also performs live art criticism as a project called 60 Wrd/Min Art Critic, which has been exhibited at dOCUMENTA (13) and several cities across the U.S. She teaches art history and criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Conversation

On the power and possibility of criticism

Art critic Lori Waxman on why sharing your opinion on the internet isn’t the same as being a critic, figuring out ways to make the invisible practice of writing less opaque, and rethinking the way art, criticism, and politics intersect.

As told to Micco Caporale, 2496 words.

Tags: Writing, Art, Process, Inspiration, Creative anxiety, Politics.

Social media and review sites like Yelp offer endless opportunities to share opinions. In many ways, it’s made everyone think of themselves as critics. How does this change the stakes or responsibilities of professional critics? Is the source of the paycheck all that separates a critic from an influencer? Why do critics matter right now?

Critics are not commentators. Critics are not influencers. Critics are experts in a particular discipline that are able to articulate their opinions about what they encounter in that field, while also providing immense amounts of context and other sorts of arguments to back up their opinions.

When I review an exhibition, first of all, I’m thinking really hard about what exhibition I’m even going to review. In the Chicago Tribune, I get one page or 1,000 words once a month to do with what I wish, and I think really carefully about what show is big enough and important enough to spend those words on.

I write about a fairly elite subject, which is contemporary visual art, and I write about it in a general interest publication. So I also have to provide whatever is necessary for your average reader to understand what the hell I’m talking about. Just at the level of, “What is this art? Why does it matter? How does it fit into the grander scheme of things?” Influencers and lay commentators do not have that responsibility.

How has the internet changed the role of the critic, and why is it important to keep traditional criticism alive?

I’m such a terrible person to ask about the role of the internet. [laughs]

I know, you hate it. You’re very low-tech.

Because I write for a newspaper! Like, I write for the most non-internet-y thing around. And I’m so old school, I’m so into legacy publications. Like, it’s killing me that [the New Yorker’s art critic] Peter Schjeldahl is dying.

But being old school is just an excuse and doesn’t really answer your question. “How has the internet changed criticism, and why do we still need critics…” Hmm, I mean, in a fairly general sense, that goes back to your previous question. Like, look. There are all these influencers now and situations that lead to the “everybody is a critic” thing. That’s why we need critics. Because everybody is not a critic. Everybody has an opinion, and everybody can distribute their opinion better than ever before. But that doesn’t make them critics.

To be a critic is a very particular vocation. It’s to know your field inside and out. It’s to know what happened before, what’s happening now. To know why something is important beyond just your particular interest in it is to be able to defend all of that contextually and historically. And it’s also the ability be a fucking good writer!

Being a critic is being a writer—unless you’re doing another form. But always, we’re talking about words here. And we’re talking about what goes into getting those opinions across in the deepest, most meaningful way possible.

You have a lengthy professional background as a traditional art critic, which is to say in print. What inspired you to turn criticism into performance art via your project 60 Wrd/Min Art Critic?

I started that project about 15 years ago when almost everybody I knew, including my boyfriend at the time — who is now my husband — was an emerging artist. They were really baffled by the artist/critic relationship, like, “How do you get a review?” A review is such an important thing to have as an emerging artist. It validates you. It helps you get more shows.

I was an emerging critic, and I also worked in art book publishing at the time. I was writing hundreds and hundreds of individual bits of copy for art books on these crazy deadlines, so I got really, really good at writing short, fast, good text about art-related material. I developed this skill set, and I thought, “Why don’t I use it to answer this question all these emerging artists have about how to get a review? Like, why don’t I see if it’s worth anything to them if I just offer the review?” But, with the caveat that it’s going to be done pretty fast. Anybody can have one. But there’s going to be a lot of them so you will get less attention in the process.

Why did I make it into a performance? I get really lonely being an art critic. I go and see art by myself. I have pretty strict rules about not talking to anyone about the art I’m looking at if I’m thinking about writing about it. And then, I come home to my office, and I close the door, and I write. Yes, eventually I send it to my editor, but he and I barely have a back and forth over it. And then, I almost never even hear from readers or the artists I write about.

Well, partially because you’re not on the internet.

True. But remember, I’ve been doing this for long enough that that wasn’t always a possibility.

Yeah.

Maybe I would be less lonely if I was on the internet…

No, don’t get on the internet.

[laughs] I don’t want to. I don’t think that’s the kind of community I’m looking for. Anyway, I made it a performance, partly so I’d be less lonely, and partly because art criticism is such an opaque process. Nobody used to know what critics look like. Nobody ever sees the act of criticism while it’s happening; you only see the end product when it gets published. And I wanted to try and make that transparent.

When I’m doing the performance, my computer is hooked up to a flat screen monitor, and people can literally see the review while I’m writing it. Even the act of writing is made transparent. There is me, there is the art, and there’s the writing happening. Maybe it’s really boring, but I’m putting it all out in the open as an experiment in making visible something that’s invisible.

Over the years, the project has evolved. You’ve taken it all over the world, including smaller cities with limited arts coverage. In what ways does inviting the public to subject themselves to your scrutiny diversify or challenge both the subjects and audiences of art criticism?

Let’s talk about the scrutiny thing first. When I started this, it did not occur to me that this might be a difficult thing I was asking anyone to do—to bring me their art and have me publicly review it. A very well-known Chicago artist who is a friend of mine told me point blank she would never participate. She hadn’t read reviews of her work, which appear in major magazines, for a decade. She just could not deal with criticism in any way, never mind this weird form of public, physical criticism I was doing.

I took this apart because it’s never been my intention to make the artist uncomfortable or even put them in the hot seat. The project is meant to be both service-oriented and experimental. It’s a service because… Like, someone might bring me their late mother’s artwork that is gathering mildew in the basement. So the review is a kind of tribute to someone who got no recognition during their life. Or someone might bring me their incarcerated son’s work because, when I write a review and they present that to the warden, it says, “This is legitimate,” and then that incarcerated person gets more time and supplies for painting.

Someone might bring me their work because they’re an MFA student, and they’re really trying to have a go at a professional career, and the more reviews they get, the better on their CV. Someone might just bring me their work because they have a private practice, and they don’t get a lot of feedback from anyone in the art world because they just don’t have that network.

With the diverse range of artists and artworks that come to me, I try to figure out what each one needs from me while being true to my own critical sensibilities and knowledge. And I feel like that’s what I offer them in exchange for agreeing to put themselves in the potentially uncomfortable situation of their work being reviewed in public. That’s not a big deal necessarily for someone who’s a professional artist. It shouldn’t be, really. But it can be an extremely big deal for almost anybody else.

Actually, I’m trying to figure out a coronavirus version of it because I’m thinking about all the artists who are having exhibitions canceled and all the art that’s not going to be seen over the next couple months because the exhibition is closed or canceled. Most of the art’s made, and it’s just sitting all by itself somewhere. If I had been the one to make that art, I’d be crushed right now, especially if I were an emerging artist.

Like, it’s not a big deal for [Michael Rakowitz, Lori’s husband] that his show in Dubai just got closed. It doesn’t matter. It was already in London and Torino, so whatever. They’ll re-open it or they won’t. But if it’s… like, I was talking to a friend who has a show up at one of the galleries on Chicago Avenue, and I think it’s his first show in years.

Oh wow.

It’s closed. Nobody can see it, you know? And I feel like that parallels some of what I provide in the normal version of the performance which is, like, I am going to look at this work of yours that you feel is not being seen either at all or enough. And then, I’m going to write you something so that you have it. And I’m going to publish that thing so that other people can read about it, too. It seems like, if I just tweak the performance and lose the live aspect, which is being lost all over the place anyway, I might have something to offer as a critic during this time.

In some ways, criticism has a curatorial quality — not only in terms of deciding what artists or shows should or shouldn’t be given attention, but also what details should or shouldn’t be included. What informs how you decide what’s worthy of attention?

Well, my answer is really different if the criticism is for, say, the Tribune or if it’s for the 60 Wrd/Min performance. They’re quite opposite, actually. With the Tribune, I think really big. I think about the entire Chicago scene. What are all the big shows during any given month, and what seems to be changing the discourse or representative of really big change in art making right now? Or, what’s something from the past that’s being dug up and is super timely? Or what am I the most excited about right now, and why? And is that “why” important enough beyond me to justify putting it in the paper?

For the performance, I don’t choose who gets an appointment for a review. That’s partly an antidote to all the people I have to leave out when I’m writing for the Tribune, which is 99.9% of exhibitions. But people who come for reviews almost always bring me too much to write about, so I pick what’s the most interesting to me. Because I can’t fake interest. I’m going to find something that interests me, somehow, and that’s what I’m going to write about.

So criticism should always start from a place of interest?

I think it’s impossible not to. Otherwise, it will lack conviction. I’m lucky that I’ve almost never had to work on assignment, so I’ve almost never had to feign interest in a subject. And I don’t want to. I think it would force my language to become really hollow. Really empty. I mean what I write. I mean every single word. Even if I might change my mind later, when I write it, I mean every single thing that I write and publish.

It seems like the act of criticism is politically charged because of who gets to do it and what they get to reveal through it. Would you agree? And if so, what are ways critics can really harness the power of their profession? What would you like to see more of in criticism?

Yes, of course criticism can be political. The way I consciously try to channel that is to think about the newspaper that I write for, which is an extremely conservative newspaper pretending to be otherwise. I mean, it’s got a very conservative editorial board and publisher. I feel like having been given a page in that newspaper every month, I’m damn well going to make sure that what I put there is an alternative political position to what’s appearing on the editorial page.

I didn’t mention this before, but that’s something else that I think about when I decide what I’m writing on each month. I think about the politics that might be inherent in that exhibition and if I badly want to insert those politics into the Tribune to counter a lot of what is there or what’s absent from that paper.

In the last two years, I feel like I’ve seen so much of what I’d like to see more of in criticism. There have been so many political crises that have bled over into the art world the last couple of years, and I feel like they’ve been boldly written about by art critics and other writers. Like the crises of representation involving Sam Durant or Dana Schutz; and the toxic philanthropy and related protest at the Whitney Biennial or more recently at PS1. Or Nan Goldin and her group [Prescription Addiction Intervention Now] dealing with the opioid epidemic through art venues. None of this was happening in art criticism — or really the art world at large, but definitely not in art criticism — five years ago. And it’s kind of been nonstop for the last two or three years.

If anything, I would just like to see more of these kinds of political, newsy stories being written about by critics and people who know their art extremely well. Because I think then you get a much more nuanced take.

Lori Waxman Recommends:

Go for a walk

Read Life After Life and A God in Ruins by Kate Atkinson

Watch I Love Dick, an Amazon series directed by Jill Soloway, very loosely based on the cult book by Chris Kraus

Do some Erwin Wurm one-minute sculptures

Listen to Boney M and dance in your kitchen, baby

- Name

- Lori Waxman

- Vocation

- Art critic, Art historian, Teacher

Some Things

Pagination