On using technology to outpace our adversaries

Prelude

Grayson Earle is a new media artist and educator. He has worked as a Visiting Professor at Oberlin College and the New York City College of Technology. He is the creator of Bail Bloc and a member of The Illuminator art collective. Recent displays of his work include Kate Vass Galerie (Switzerland) and the Brooklyn Museum (USA). He has presented his work and research at The Whitney Museum of Art, MoMA PS1, Radical Networks, the Magnum Foundation, and Open Engagement.

Editor’s note: This interview is part of a series we’re working on with Pioneer Works and Are.na, in advance of this year’s Software for Artists Day.

Conversation

On using technology to outpace our adversaries

Artist, activist, and educator Grayson Earle on the possibilities of collective sabotage, what it’s like to teach during a global pandemic, and realizing there are no real rules when making art.

As told to Willa Köerner, 3165 words.

Tags: Art, Culture, Technology, Success, Focus.

What’s weighing most on your mind right now? Do you have any thoughts to share as we all feel around in the dark for how to get through this moment?

The main thing on my mind is my students. I’m teaching at Parsons, and now, all the students who were living in the dorms have been evicted. I have one student who was like, “I don’t know what to do now that campus is closed, now that I have to go back to Korea.” So just the material realities of caring for students has been tough. And then also knowing that they’re paying all this money in tuition for something that has changed entirely. I’m trying to do what I can for them, but also trying to care for myself and making sure that I don’t go overboard by completely revamping my entire approach to the semester.

I definitely worry about this long-term, in terms of what this will do if the university, and universities in general, see this as an opportunity to move more things online and cut costs. I imagine if they amass a bunch of archived lectures because of this crisis, there’s the cynic inside me saying, “Well, what would they need us teachers for if there’s a bunch of lectures out there that they can have students access at any time?” I don’t know. I think that they might be looking at this as an opportunity to save money in the future and change the face of education a little bit. So I’m worried about that, I suppose.

From a practical standpoint, how have you been adapting your lesson plans?

The class is called “Virtual Environments,” and it’s mostly game design. We were just starting a VR unit, so there were groups of people sharing headsets. Normally they would meet up, whether on campus or elsewhere, to come together and build and test whatever environment they wanted to make.

Unfortunately, only one in four students has a VR headset right now. If we had foreseen this, it would have been kind of amazing to meet in VR, and create our own meeting environments and stuff like that. It’d be really interesting. But just in terms of the equipment necessary, it’s not really possible unfortunately.

Generally speaking, I’m trying to map out my lessons really well, documenting them, putting them on GitHub, recording them as videos so that students can watch them whenever—because now I have students who are back home in Korea and Vietnam who can’t tune in for the live sessions. So I’m just trying to hear out my students, figure out what they need to learn, and then mapping things out with really, really good notes so everything is easy for them to follow along with.

It’s tricky, because normally in my in-person meetings I can suss out what things they’re not understanding and help them one-on-one, but now I think it’s most important to provide them with information to be able to do that themselves.

I also have some students with health problems that keep them home fairly regularly anyway, so it’s definitely made me consider that maybe this sort of thing should always be part of the classroom, as an option for people with less access to being in the physical space.

Do you think that a fully digital education could ever really replace the experience of going to school in person?

I don’t think meeting in virtual spaces can really hold a candle to meeting in real life. I think there’s just so much… I mean, even if you just look at human communication in general. We know that so much of it is nonverbal. And you get a little bit of that doing live video chat, but I think there are all sorts of things going on that it really takes being in the same space as someone to be able to empathize with them when you’re communicating. Just being able to see everyone at the same time, rather than just one face at a time, changes things. Reading the room becomes a lot more difficult.

Overall, I think people’s relationships to one another change when there’s this mediation between them. When you’re trying to teach people to work in groups, a lot of that is empathy and accountability. And these sorts of things become a lot more difficult in a more mediated, digital situation. So, I’m really worried, again, that this is a sign of things to come.

Ai Wei Whoops; aiweiwhoops.net

To shift gears, you’ve done a lot of art projects that feel like activism. Do you see your work as activism?

Yeah, I think so. I’m not so shy about the distinctions, like, “Is it art? Is it activism?” I think these things are kind of funny constructions. For me it’s never a question of, “Is it art?” But, what does it afford us to call something art that we might be more comfortable calling activism? And then also, of course, I think it’s the responsibility of artists to produce culture that alters the course of what’s happening and shifts the conversation. And so, yeah. I feel pretty comfortable moving between the two identities, artist, activist, teacher, all these things seem the same to me.

How do you decide which projects and what type of work to take on? Is it the kind of thing where you just sense that something is the right project at the right time?

Well, it kind of depends on which context we’re talking about. I’m part of this artist collective, The Illuminator. We basically own a van with a really powerful projector, and for the last ten years we’ve been doing large-scale guerrilla video projection onto buildings and otherwise. We’ve been all throughout the United States, Europe, and South America, and essentially we’re putting large protest signs on site-specific buildings. For that project, we have very strict guidelines we’ve made for ourselves about not doing commercial work, and taking on projects one at a time while trying to balance getting the money that we need for things like insurance, parking, fixing a van that is constantly breaking down, that sort of thing. Sometimes we’ll get offers from brands like Nike to do a big projection, and we decline so that we can maintain being a people’s project that isn’t beholden to any corporate interests.

The Illuminator; photo credit GULF Labor

In terms of my own work, I feel drawn to taking on projects that can have more of an impact than just “raising awareness” about a political issue, for example, because I feel like we’re at peak awareness. Everyone knows what’s going on now, for the most part. So for me it’s more about doing projects that can intervene directly on the systems themselves, rather than talking about those systems and why they need to be intervened upon.

I like to look for points of leverage that I can intervene on, whether that’s using video projection to get around laws that prohibit you from doing things like graffiti or something, or whether it’s using the rampant speculation of cryptocurrencies to generate money to pay bail for people. For me it’s about looking at technology as a way to outpace our adversaries, and trying to utilize it creatively to circumvent things.

How do you define success with those types of interventions? Is it a direct, 1:1 kind of thing? Like with Bail Bloc, for example, were you able to bail a lot of people out of jail with the money the project raised?

The exact number of people is sort of intentionally unknown to us, because we preserve the anonymity of everyone that the project is able to bail out of jail. That was also a mandate from our partners, the Bronx Freedom Fund. But still, we do know that people have been bailed out directly as a result from that project. The average bail is something like $900, and the project has raised about $10,000. So there is a way to kind of calculate the discreet successes of that project. And I like that. I like that there’s a way of being like, “It helped people directly.” Even if it bailed one person out of jail, it would have been totally worth it.

Then there’s the broader picture of like, “Well, the project is also a rhetorical device to pry open a conversation about bail.” And the victories around that are much more difficult to quantify. But we do know that as a result of our project, and obviously many other projects working on similar issues, the conversation about bail has changed significantly, and we are seeing some legislative changes going on as a result of that, I think.

Bail Bloc; photo credit Kyle Depew

I love The New Inquiry’s Rhetorical Software work. It feels like a whole new way to think about how digital technology, or software in particular, can be used. Can you explain the idea behind it?

The Dark Inquiry’s Rhetorical Software division is now on hiatus, but the two projects put out as part of that project are Bail Bloc and White Collar Crime Risk Zones. White Collar Crime is probably the most salient example of Rhetorical Software. It takes the idea of those crime heat map websites, which are basically just vehicles for gentrification. People can log on and be like, “Oh, I want to live here. Oh, but there’s crime around there, so maybe I’ll live over there instead.” White Collar Crime takes that forum, but occupies it to show the real crime—financial crime—that has a much broader effect. People simultaneously stealing tons of money from other people, and behaving in such a way that has cascading effects leading to unemployment and homelessness and so on. So, a crime map [showing where financial crime takes place] is a way to point to the fact that like, “Oh, right, we are thinking about crime in all the wrong ways.” Technology is constantly being used as a way to reify capitalism, when it could be used in exactly the opposite way.

I’m most interested in work that’s transgressive. Recently I’ve been working on a toolkit for workers who are striking and unionizing. It’s a bunch of tools for sabotage in the workplace that can help workers gain leverage in situations where they don’t have a lot of autonomy. One of the prototype objects that I’ve created is a device that shuts down WiFi networks in an area, because something I’ve noticed about the modern workplace is these offices are just full of people working on their Macbooks or whatever at desks, and so if there was no internet in the area, then work would become impossible. So that enables a new negotiation tactic for workers.

This has also been a research project for me, where I’m looking at the history of objects that are antagonistic in the workplace. It turns out that the word “sabotage” itself comes from the root “sabot,” which is a French word for a worker’s shoe. Apparently when the workers were absorbed into industrializing Paris, they were met with all sorts of unfair working conditions of course, and so in situations where they weren’t being treated fairly, they took to throwing their shoes into the Jacquard looms, which would break because they’re so delicate. So, management became afraid of the workers’ ability to break things, and started to pay the workers better. Collective sabotage gave them a little bit of say in the whole situation.

How do you work through the tension of digital tech feeling like an expansive creative medium with so much untapped potential, while also seeing tech as a conduit for doing a lot of harm these days?

Technology has become the way that I do everything. It’s exciting because I know it well and I know the algorithms for it and the various points of intervention, whether it’s cryptocurrency mining or devices that can shut down WiFi networks. But something like shutting down a WiFi network is an anti-technology technology, so I don’t know.

“No ethical consumption under capitalism” is a phrase that goes through my mind when I’m thinking about using Google Drive to do political organizing, or whatever. There are some interesting projects that try to address these tensions. At Radical Networks a couple of years ago, someone created a Google Drive extension that encrypted everything that you stored to it, and then enabled you to decrypt it yourself. It just used Google’s platform as file storage, and revoked their ability to look inside your files or extract any useful data from it. These sorts of things are really important to keep thinking about, but overall we definitely need to be producing infrastructure and the tools ourselves.

It’s difficult. This may be sort of a ridiculous example, but there’s been such a resurgence in leftist thought and critical theory just through memes, and it seems to be a somewhat useful organizing technique. But I always come back to the fact that these memes are being shared on platforms that we don’t own, and they’re being produced with tools that we don’t own. And so I do think ultimately, it’s important to start to take control of those things.

The other tricky thing about technology is that if you are literate in creating it and understand how it works, you’re in something like the top 1% of users. So it feels like there is one class of people who are able to create the tools or intervene with the tools, and then there’s the rest of us who aren’t good at coding and engineering and don’t really understand how it all works. We’re just the users.

Yeah. There’s so much to say about that. For one, with the software industry and tech companies paying what they do, it keeps a lot of people out of doing activism with technology in a sense, because they can make so much more money just working for one of these major companies rather than producing infrastructure that can work against them. And this is also why I see my artistic practice, my activist practice, and my teaching practice as the same thing—because all of those identities are striving towards the same goal. When I’m teaching I’m trying to bootstrap another generation of people who do understand this stuff, so that they can comment on it and they can challenge it and they can act as interpreters for other people who maybe don’t understand it.

But it is a bit like David and Goliath because there’s just so much power and money on the other side of things.

This is sort of a dark question, but is there any hope for intervening at a larger scale and creating actual momentum around using different tools that are not owned by huge companies? Or have we already moved past that point?

Do Google and Facebook have more power than the state? Maybe. I mean, I think Europe is definitely something to look to in terms of starting to regulate against these big companies. It’s definitely possible to curtail them, with the dream being to change them into public utilities at some point down the line. Crazier things have happened, right? But we would need something like Democratic Socialism in order to tackle any of these things, and I think this current crisis, at the very least, is exposing the importance of something like that.

What we do know is that crises precipitate change. It’s just that the capitalist agenda has always been the best at utilizing crises, like Naomi Klein writes about in The Shock Doctrine and so on.

Do you have advice for people who are trying to walk that line between living up to their ethics and their ideals, but who also just need to make a living? Especially technologists?

It’s such a difficult question. I mean, obviously privilege intersects with all of these things, and so it’s difficult to give a general answer. When people ask me, “How do you find the time to do this?” It’s like, “Well, when I moved to New York I lived in a co-op with 15 people and we dumpster dived and pooled resources and my rent was $400 a month.” So I took the pressure off of myself that way. I think forming communities of mutual aid is really important to being able to do this sort of work.

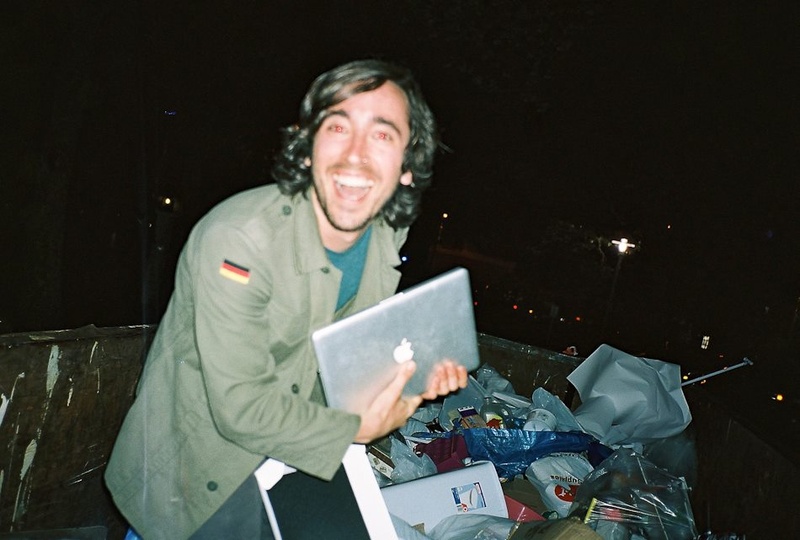

Found a Macbook in the Pratt dumpsters on move-out day a few years back

The real issue at play here is that there’s often no social safety net. There’s no support network in a place like America that gives people freedom to do certain things, because ultimately we have to pay for rent and health insurance and all of this stuff. So doing the creative, important work, the radical work, and then also thinking about how we can make political structural changes that can support this sort of thing down the line, is tricky. For some people, the solution looks like Universal Basic Income. For other people, maybe it looks like rent strikes or Medicare For All. I think that taking whatever privilege you have, and leveraging the hell out of it, and trying to create institutional change that can help other people to do this sort of work, is really the way forward.

Is there anything you wish you could tell your younger, struggling self? Something that would’ve taken the weight off your shoulders?

I think I would’ve told young punk me that there’s no such thing as success, really, because even if you get a show in a museum or something, it doesn’t stop there. No one’s going to track you down and want you to make more things. You just have to keep going.

I would also say that at a certain point, I realized that no one has any idea what they’re doing, and that’s really freeing. I mean, there are some people who kind of know. Some scientists and doctors and that kind of thing. But in terms of producing culture, there are no rules. We’re all making it up as we go along. And no one has sight of everything. So yeah, you just have to make things and see how they turn out. Maybe you’ll stumble upon something that’s great.

Grayson Earle Recommends:

- Hito Steyerl - Duty Free Art

- Alfonso Cuaron - Children of Men

- Ursula K LeGuin - The Disposessed

- McKenzie Wark - Hacker Manifesto

- adrienne maree brown - Emergent Strategy

- Name

- Grayson Earle

- Vocation

- Artist, Educator

Some Things

Pagination