As told to Resham Mantri, 3593 words.

Tags: Art, Inspiration, Process, Independence, Success, Education.

On being truly obsessed with your work

Artist Adam Helms on balancing optimism and pessimism, navigating the social niceties of the art world, and maintaining a lifelong obsession with your creative work.Do you think that you’re consciously exploring aspects of masculinity in your work?

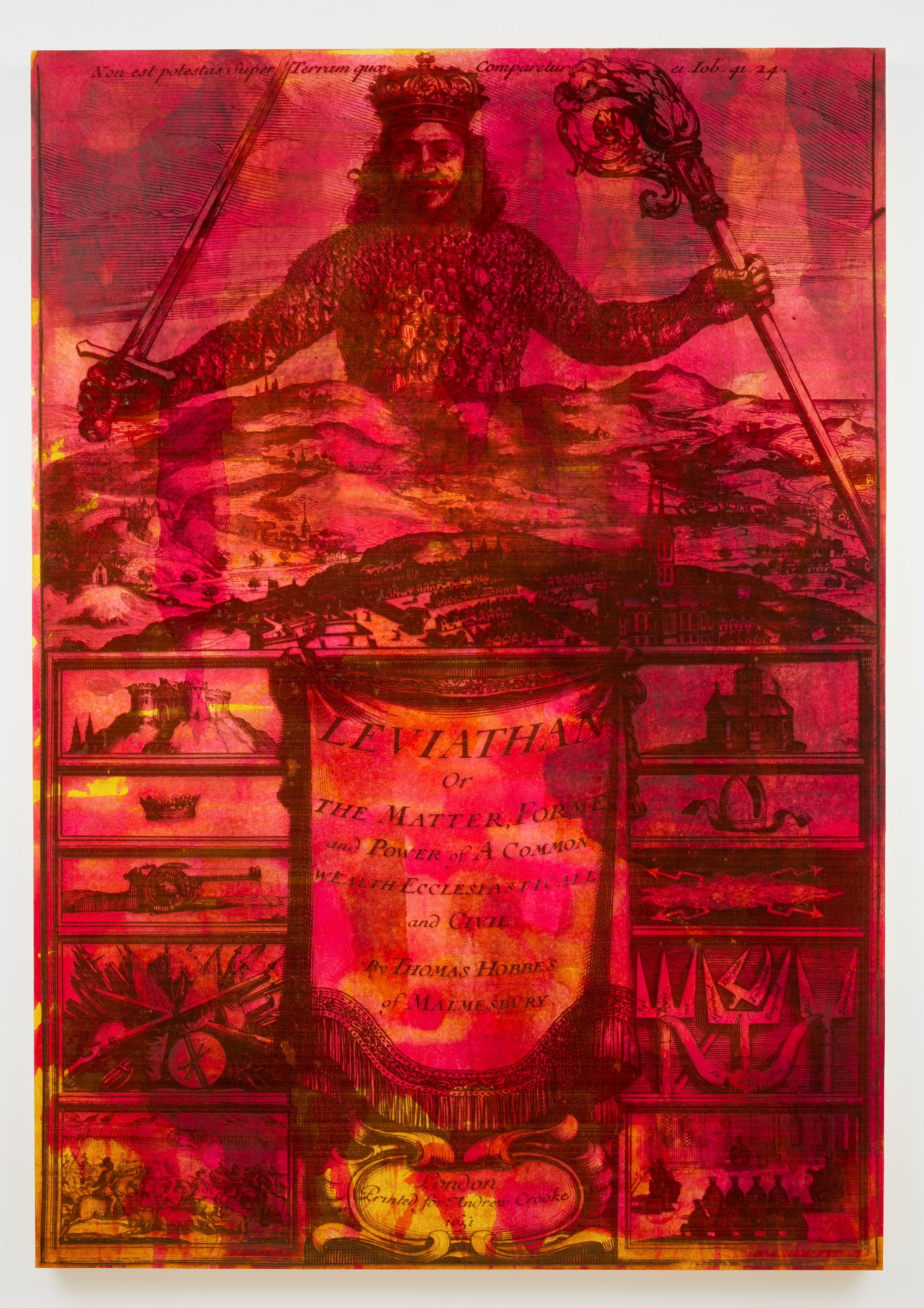

There have been periods and bodies of work that yes, do explore a male identity, and it wasn’t an intention of mine, like, “I’m gonna explore maleness.” It was something I came to as a result of strange interests I have around certain source material images of political situations that dealt with the male identity.

It made sense that I was just coming from a certain set of experiences that obviously I understood about myself, as a hetero male, and about relating to the world. About projections onto that sense of identity, an investigation of certain male positions of power. When I look back on it, we would say now, it was about toxic masculinity to a certain degree.

There was a kind of critique, and I was trying to find a way to make drawings that could toe this line between romance and subversion. Psychologically, there was a sort of romantic intent, but at the same time, it was also a critique. So I saw it as being semi-subversive at the same time.

That reminds me of a quote from your gallery, which talks about the sensations that your work evokes in the viewer, specifically, it said “…the sublime here points to the conflicting emotions of fascination and fear, feeling both attracted and appalled while the viewer is at a safe distance from the depicted subject.” What’s really interesting for me about some of your pieces is that dichotomy, like feeling both…

An attraction and a revulsion.

Is this a sensation you’re actively seeking in your art or within viewers?

It was more just surrendering to the obsession that I was interested in, and then sort of letting that develop and grow. That is part of what a studio practice—for me, and for a lot of artists—is about. How those things develop over time, and develop through searching and an investigation or something, rather than just trying to make interesting pictures.

The conceptual intent behind a lot of that sort of starts to formulate itself after just making work, basically. It’s not put forth as this particular intention, it becomes just part of the process of making the work.

Is seeking answers, within yourself and the world, a motivator for you?

For me, generally speaking, interesting, successful artwork is something that presents questions, rather than answers. Even if the artist is searching for particular answers to these things, the questions that are put forth are what makes visual art powerful.

At this point in time, in the popular culture, we’re all trying to understand what previously was thought of as extremist ideology. There’s a slow understanding that it’s more mainstream than was previously acknowledged.

Absolutely.

Your work reminds me of that.

There was a time when I was a grad student at Yale, and a visiting artist who I admire, Sarah Oppenheimer, and I were looking at a lot of the source material that I had put on the walls of my studio. This is around the time of the invasion of Iraq, and she said, “Wow, the world has caught up to your work.”

I’ve always remembered that. What I was depicting in my work was that sort of amorphous identity, that wraith-like persona, rather than trying to make specifically political statements. Because I don’t make political art. I think political art can be used as propaganda.

In the late ’90s, early 2000s, no one was interested in the things I was reading about, which were the post-neoliberal ex-communist guerrilla movements. A lot of these rebel groups that were still functioning at various parts of the world seemed to butt up against this idea of civil society. It was very much the triumph of the beginning of neoliberalism, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of communism, that felt like it was a globalist moment. It was very new and extremely idealistic. Technology and free trade are going to bring everyone together, that was the promise. As time has gone on, these themes, personalities, images, archetypes, generally male personalities have become something that is rather frightening and is becoming normalized to a degree.

Despite recent events like the Iraq war, the capacity for humans to be societally optimistic in light of all clues to the contrary is an interesting thing in and of itself. Maybe it talks to our capacity for horror? It’s interesting what people either consciously or not choose to forget, in pursuit of sanity, or good feelings.

I think we’re in a moment where the world seems to be devolving into tribalism versus the promise of neoliberalism and this utopian idea that technology is going to unite everyone and disintegrate borders. In response to that, there’s a balance in culture now where some of these themes are consciously being addressed. At the same time, there’s a move towards pop or things that are representative of frozen optimism or a kind of suspended animation of feeling optimism.

Do you think of yourself in terms “optimistic” or “pessimistic?”

At one point I referred to myself as a “cosmic pessimist” but as time has gone on, as I’ve found love in my life, strangely enough I’ve become a little bit more optimistic. I think I’ve come to realize that no matter what is happening, or what the perception is, any complaints you and I would have in general, while living in the United States compared to other places, are pretty absurd.

We have it pretty great, and I think you can make your personal world one filled with beauty and optimism and great moments in life and the world if you want to. I’ve realized it’s a choice whether I want to be optimistic or pessimistic, so I’m trying to veer more towards optimistic. People who are completely pessimistic, at a certain point, you don’t wanna be around them, and it blocks me from my friends and experience of the world.

Yet at the same time, on a meta level, speaking of politics and the world, I’m extremely pessimistic. I do think things are actually worse than most people see them, meaning that everyone has an understandable and vociferous obsession with Trump, as though once Trump is lifted from the stage, that things will stabilize to a certain degree, but I think the cat is out of the bag. He’s a symptom of something larger, and it’s a wave that’s taking over the whole world.

How do you navigate the realities of the art world in terms of its pace, and the extreme wealth surrounding it? What’s your way of dealing with it?

I’ve always had a lot of reservations and discomfort with the art world in terms of the way you just described it, in terms of being kind of a wealthy progenitor of cultural affectation.

The art world in New York, at least, can be managed by complex groupings of social relationships, just meaning if you’re friends with the right people and with centers of power and just generally people in the art world, that can propel an artist to have an easier ability to be viewed, and to have agency and presence in the art world. If you shy away from that social part of it, it can create a difficult set of circumstances, and that’s certainly the direction I’ve taken by choice and also just due to the fact that my priority needs to be the exhaustive process of making a work.

I could always make time to be more social, but I tend to make my priority making work. I have begun to live a relatively hermetic life in those terms as opposed to exposure in the art world, but I also have a belief in myself and my work that at the end of the day, the measure will always be the work itself. This is, for me, a long life, not just a career. Not just trying to make some money, it’s a life, it’s a stance, it’s a position that, whether I like it or not, is something that I’ve embraced and I can’t really do anything else. I don’t really want to do anything else. So this is who I am.

I would rather watch films that I really like, I would rather read, I would rather just kind of always be working on my work.

I’m also grateful wherever I go to run into my friends and other artists and colleagues and people that I believe in and believe in me, so I don’t ever feel totally alone or alienated, I guess. I just don’t like to kiss the ring. And that has probably been beneficial in the long run, and I feel good about it, but it hasn’t been easy for me. But yeah, that’s basically what I’m saying in a nutshell. I don’t like to kiss the ring.

And you’ve been doing it for a long time. Have you had any other careers or jobs?

No. I briefly had a period where I did freelance web design and animation when I graduated from RISD in ‘98 until about 2001, before the .com bust. In that economy, a lot of my friends in RISD who were musicians and artists moved to New York and were just getting these gigs. It was easy to do freelance work. So I could spend a lot of time in my studio.

But once I was in grad school at Yale, from 2002-2004, I started showing my work before I’d even graduated, and I’ve never had any other day job or anything else since then, which I feel fortunate about. I just followed the gust of wind in my sails at that time.

A lot of people in my generation find themselves at this mid-career point and things become a little bit more difficult. The pace changes, and there’s always a new generation of artists for people to look at, which is important. It’s really just this idea of just not stopping, and sustaining, and just finding a way to keep it going.

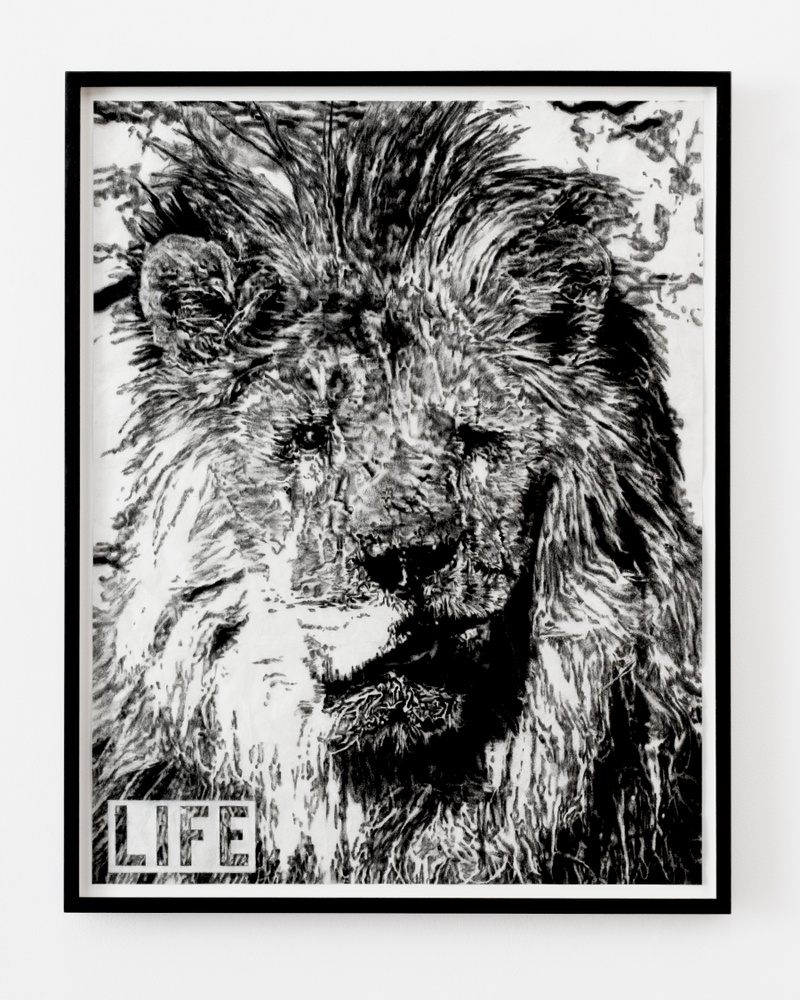

In general, making paintings and drawings is just what I do, it’s what I want to do, it’s what I’ll always do, and I believe in it. I still believe in handmade objects, and in the autonomy of the art object in a culture that has been Instagram-ized, in which images and things become swipeable and ephemeral.

But it’s good to see your work on Instagram, I will say.

It becomes a virtual gallery in which I can put up archived images from bodies of work and shows that no one really ever saw because they were in Europe. Also, on Instagram I’ve found things that are incredibly interesting to me. I follow a bunch of feeds of antiquarian images and paintings and engravings from the 13th century and Medieval art. Everything is distilled down to that particular size, so it becomes kind of democratic in terms of how does the image function at that size, etc. There’s no competition in terms of the format, everything’s the same size.

It helps me re-examine my own work as I go back and find images to post. I rework images and look at them and curate them myself. It helps me look back on my work and what I think is strong and weak or what worked and what doesn’t. Also, there’s a lot of Instagram and social media that I detest.

So you explore different techniques in your art in terms of material, painting as well as things that are sculptural, and you also work with images from the internet. Can you talk about how you approach each piece and your studio process?

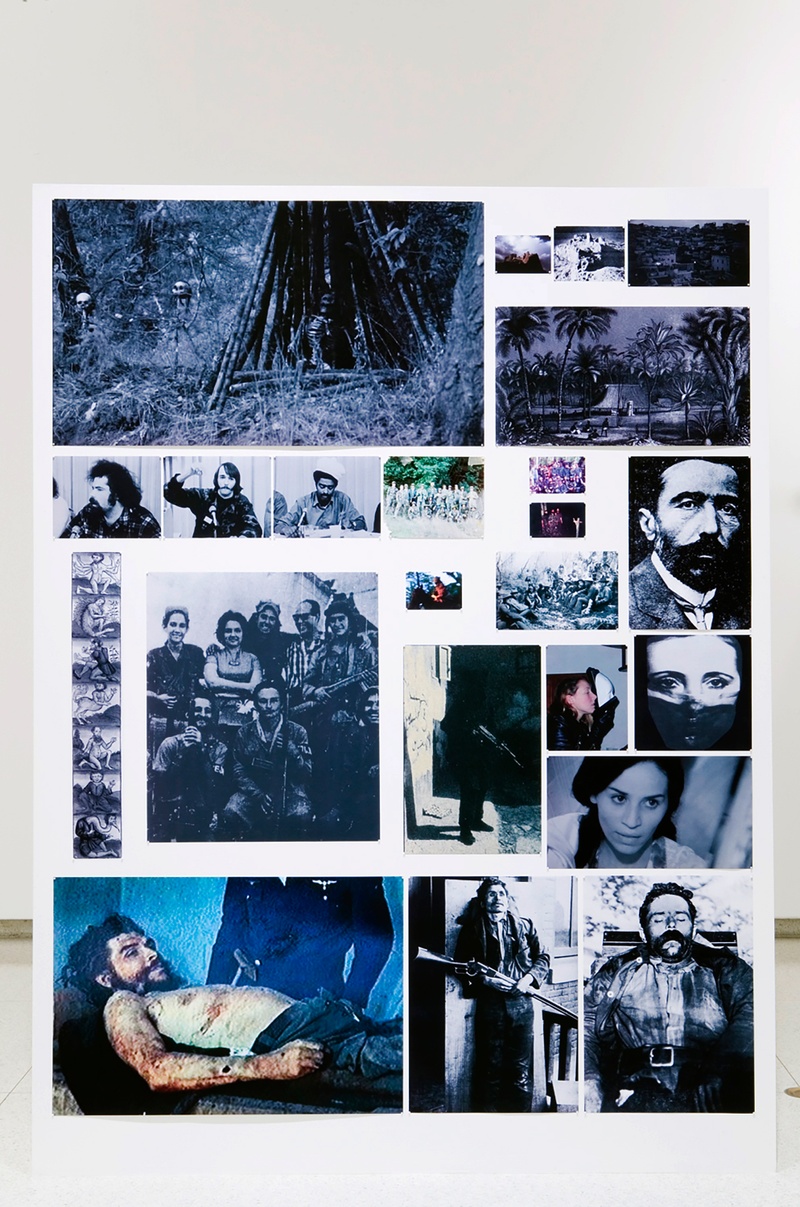

I think that working from an archive of source material, generally speaking, has been kind of the Rosetta Stone of my work. There are some images that I’m attracted to that I want to utilize and make into art objects, but aren’t necessary to function as paintings or drawings. They function better reproduced in a photographic way, as elements within sculptural installations, or as conceptual complements to the paintings. When I make an exhibition the paintings and the drawings tend to have a certain importance and autonomy within a body of work.

By utilizing the source material, and maybe at that particular time, I’m gonna make drawings of certain things and then that will be complemented with a light box. Or I’m gonna make paintings and the drawings, which are very photographic and obsessive and have their own purpose and autonomy within the body of work, aren’t meant to just be a display. So I find that certain approaches—whether it’s painting or drawing or assemblages, photograph reproductions—all take on a certain conceptual authority within a body of work or within an exhibition, rather than just any one thing that I do.

And sometimes I almost wish that there was just that one thing that I did, because it would make it a lot easier, I guess, but I wouldn’t feel satisfied. There’s a constant search and an anxiety, an ADD-like energy I have at times. If you took certain years and certain bodies of work and put them in a room together, the average viewer may not recognize and see it all as my work, but I think over time, and if you look at it as a body of work, it starts to make sense. Artists like Mike Kelley and Sigmar Polke, are two examples of artists that didn’t adhere to a particular style or a particular formal set of concerns with works.

Can you talk to me about the untitled portrait series? I’m in your studio, looking at them.

You’re talking about the heads?

The heads, yeah. You can see the shape of a portrait, but there’s no identifying details…

Yeah, so there was a body of work that I made around 2005 which were these ink-on-mylar portraits that were basically ink pools in the shape of hoods, or heads, but they looked like they could also be map-like, topographical, or blood pools. I was making these obsessive graphite drawings leading up to those that were very time consuming, so I wanted to find something that was a little bit faster and more immediate, and just different. A process that had the implications of chance in terms of making it.

So these ink on mylar experiments then evolved into these portraits. I made a huge piece and a new series based off Gerhard Richter’s 48 Portraits—the men of civil society, the famous individuals, scientists, writers, poets, the sort of shadowed history of that colonial European history, was to me about these heads and these hoods, this amorphous non-identity.

In talking about ideology and about non-portraits as well as the shadows of a colonial history, I’m interested in how these things can represent a universal existential experience in a portrait.

So I’m very steeped in the idea of a portrait, of a head. It makes me think of some of the artists that I used to look at when I was at RISD, like Frank Auerbach and Francis Bacon. Francis Bacon was the first painter I saw who just changed everything for me. It all wraps around this interest in a mask, going back to the surrealists and Max Ernst, and the idea of masks throughout culture, even looking at tribal masks from South America and from Africa. I’m interested in what those meant in culture and the kind of cult qualities they can at times have, just the idea of what a mask does.

How did your youth or upbringing, and the music you listened to, shape your practice?

I grew up in a stable middle class family in the desert in Tucson, which culturally speaking, I guess, would be like California in the ’70s and then in the ’80s. In the beginning it was Xerox flyers of all these punk shows, hardcore flyers, and often there were always pictures of Reagan, with a swastika on his forehead. Very anti-conservative, and very rebellious.

The first time I went to the punk record store in Tucson, you just walk in and there is everything you can imagine, Black Flag Logo, Motörhead, The Misfits, it was just something… I also developed this obsession with horror movies and gore, and for some reason my parents would always let me rent a lot of these films, even those that were a little bit extreme for my age.

So I got to be interested in these kinds of extremes. Extremes of representation, and everything to me that was just outside of the mainstream of what I found to be the kind of really uninteresting, boring, middle of the road nuclear family, American culture that I grew up in—middle class culture.

My grandfather, was an artist, and he had an apocalyptic theme in his work. He always had these crazy dystopian science fiction books around. So my first exposure to art was not the kind of classical European post-war art—it was very American, but also comic books and sci-fi art. And some of these horror films. I spent a lot of time reading books and looking at magazines and finding images I liked and making drawings, like drawings from punk albums, or whatever hardcore album I had at that time. It was that combined with really weird creatures and science fiction and psychedelic high school dude art.

Do you have any advice for people starting or at some other point in their career in the art world?

Just make sure you’re obsessed with the work. It shouldn’t be about recognition or money, it needs to be an obsession that you can treat like a relationship, meaning that there’s gonna be ups and downs, and it’s gonna evolve and change over time, but it’s something that you always need to be able to come back to in terms of your belief in yourself and the work, a belief that you can’t do anything else.

If you believe that what you’re doing, whatever your work is, is not a choice—that you have no choice but to do it— then you’re on the right track.

Don’t be seduced by the commercial value of certain artists and certain artworks as a means to an end—that it means success—because all of that is ephemeral. And don’t be seduced by late capitalism. Just treat your work like it’s the only relationship you’re ever really gonna have.

Adam Helms Recommends:

- Mark Fisher – The Weird And The Eerie – 2016. Repeater Books.

Fisher’s final book, published just months after his suicide (RIP). Fisher’s voice as a theorist and Capitalist critique was urgent and essential. He will always be missed.

- Kolumba Museum (Kolumba Kunstmuseum), Cologne, DE.

At the Kolumba museum you can see a Richard Serra sculpture within a preserved medieval exterior space. Or a Jannis Kounellis in a space with heads and busts that date back to late antiquity. Or unearthed Roman Ruins deep in the ground surrounded by modernist walls that allow natural light to bleed in and illuminate the view. History becomes a level plane. The space itself, the lighting and the meticulously hung installations only add to a sense of a Borges-like experience. A magical dislocation from the world into a set of spaces that seem exist of outside of temporal reality. One of the most unique museums around.

- Stephen Ellcock’s Instagram Feed. @stephenellcock.

Steven Ellcock’s page is a beautiful revelation within the dearth of visual information that is Instagram. Ellcock has an eye for images like no one else I can think of on IG. Like an evolving compendium of images that could comprise an ongoing Aby Warburg “Mnemosyne Atlas,” or as Ellcock say’s: “the ultimate virtual ‘Cabinet of Curosites,’” he mines historical and contemporary images to create an archive of art and visual artifacts that never cease to leave a feeling of curiosity and optimism.

- The Standoff At Sparrow Creek. 2018. Dir. Henry Dunham.

Dunham’s first full length film is akin to Alan Clarke’s Elephant (1989) meeting a David Mamet script. Pointing to paranoia, posturing and an ethos of libertarian violence run amok, a cast of no more than 8 actors–shot with brilliant cinematography and acerbic gallows-humor dialogue—imagines a film that will become an important fiction dissecting the toxic masculinity of this particular era. Fans of the TV series Fargo and John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) take note.

- Chris Hedges lecture: “American Anomie at The Sanctuary For Independent Media.” 2018.

A speech that can be found on YouTube, in relation to his current book: America: The Farewell Tour (2018. Simon & Schuster); Hedges articulates his views of the US as a dying empire, rife with the finality of corporate control, corruption and fraying social bonds. Hedges writing is unflinchingly direct, pointing to painful truths at the core of society–his words point out the underlying reasons of America’s poisoned and melancholic state of affairs.