On activating the power of language

Prelude

Alexandra Grant is a Los Angeles-based artist who utilizes language in various forms to explore identity and power dynamics. Through media such as paintings, sculptures, films, and photography, she examines the infinite perspectives of text. Her grantLOVE project is an innovative philanthropic platform harnessing a bold trademark to generate funding for individual artists and charities. Grant also recently launched X Artists’ Books—a publishing platform probing the deep potential of storytelling.

Conversation

On activating the power of language

Artist Alexandra Grant on making a career out of her lifelong obsession with words, the value of having an amateur’s mind when it comes to creative work, and refining and defining our notion of love.

As told to Mark "Frosty" McNeill, 2550 words.

Tags: Art, Inspiration, Success, Creative anxiety, Beginnings, Collaboration.

So much of your work is connected to language. I’m curious when you first discovered the power of language on a universal level?

I think that we are all storytellers. I remember as a child trying to understand as I read or listened to a story, the efficacy of language—the difference between a written story and a narrated story. I’ve been thinking a lot about the nature of words like “god.” In my little head, for example, I would lay in bed at night and say, “Who gave god the word ‘god?’ What was there before?” I would create these little philosophical noodles about naming things. If you name something, then something else had to have existed before it. It was a very gentle six-year-old existential crisis about the way naming works, and the way speaking about experiences work.

Does your experience exist before you put it into language? Say it’s raining and you’re experiencing rain. You tell yourself in words about the rain, right? “It’s raining. It smells that wonderful smell of the earth. I’m wet, I need an umbrella. The sky is green-tinted.” All of those experiences, we tell ourselves about them in words. So, as a child, I was very aware that language came in to the bodily experience in one’s own mind, and I weighed the variety of ways that the words created our own experiences almost in retrospect, right? Because we were naming them.

I think we’ve been captivated, as we should have been every day during her life, by the death of Toni Morrison, because it’s allowed us collectively to express our admiration for her. One of the things that has blown me away about her work over the years is the sense that she was able to understand not just a gendered gaze, but a racialized gaze, and that she saw the role of literature as being this lightning between any human’s experience and writing. Any human has the right to name god. She saw that as her right, to name what she found in her experience to be divine and worthwhile. I think there is no more important point for artists to understand—that their experience, no matter their gender, race, class, nationality, or religion, has validity and is worthy of art or literature.

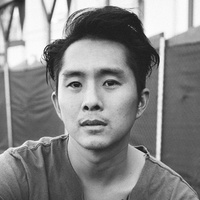

Alexandra Grant, Antigone 3000 (3), 2018, Collage, wax rubbing, acrylic paint and ink, sumi ink and colored pencil on paper

I can’t help but think, “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.”

I love that Gertrude Stein quote, because it’s so playful and yet it’s really talking about structuralism in language. Like, who has the right to name and do I accept the naming that has been naturalized?

I like the way you flip things, your mirror-image reflections. In your work there are these Rorschach test-like inkblots with text. What’s the driver of your desire to play with words?

When I was studying painting, I was familiar with art and I was familiar with artists, but I wasn’t familiar with the professional side of being an artist. I just remember looking around at everyone else who sort of seemed to be scrambling for some idea of success and a career that involved making specific artworks for a trajectory that they defined as group shows, then solo shows, galleries, and museums. My question was less about what I would call a tactical achievement and more about, “Well, if I’m going to be doing this for a long time, what is going to interest me?” So, in my late twenties I sort of looked back at my life until then, you know, the mini-retrospective in one’s own brain, and said, “The thing that has interested me throughout my life has been reading and I’m pretty sure that moving forward, I will still be reading. So, how can I make my reading practice, my enjoyment of narrative, of storytelling, central to the work that I want to do as a visual artist?”

It seemed to me in doing research in graduate school that there had always been a history of storytelling in painting. Even in abstraction, it’s a revolt of how narrative is told. It’s a symbolic storytelling. I really wanted to look at the patterns I’d found in poetry and narrative and rewrite, as an image, these texts. I wanted to embody literary works. My work was a celebration of writers. The work became about how to embody in the most clearly interpreted way, their ideas and text. My misinterpretation became part of the work, so that my paintings, especially when I was working with the hypertext pioneer, Michael Joyce, were about the experience of reading, which is such a visceral experience. I could paint that energy, in choosing the colors and gestures.

I had so much fun in a way, being an amateur, which we think of as someone who’s just a beginner, but the French actually think about as a lover—a true fan and supporter. For me, the paintings really came out of being an amateur of literary texts—a fan of writing and wanting to elevate it into the spaces of painting.

People come to see my work and there’s a sense that they’re decoding it. It’s a visual code but also a written code. One of the most fundamental traits that we have is that desire to decode things, to understand the mystery of it. So, part of what I’m doing is creating symbolic registers that exist on multiple levels. There are visual compositions—color which operates on the unconscious in certain ways, scale, the thickness of the paint—but there’s also how the words become symbols and function in languages of abstract painting which are highly-coded, because they talk about histories of painting that were more exclusive to men and were used for political purposes. I think so much of art becomes exclusive when people pretend to be experts all the time. It really narrows down who is allowed in. So, I think that opening up through amateurism, in a sense of loving things, is great. To say there is value outside of expertise, because expertise was exclusive.

I’m fascinated with the idea of amateurism and the beginner’s mind in Zen Buddhism. There is a Shunryū Suzuki quote, “In the beginner’s mind, there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.” When you’re working with youth or on a collective painting, is there anything you pass along as a tactic to help unlock possibilities?

When I first get a group of people together, to make any kind of project, my question is always, “What are your weaknesses?” Because I think, like in any interview process, people give what we would now call the Instagram version, the highlight reel of their lives. We know those are wonderful moments but what we really learn from are those moments that we don’t post, right? I love what happens when you have a group of people and you talk about failures because those are the richest, most fecund times. It also turns the conversation from a sort of posturing to a sharing position. When you recognize, “Oh, I tried doing this very ambitious project and it didn’t come together because we didn’t have resources,” suddenly you can talk about economies and money without it being this awkward thing, right?

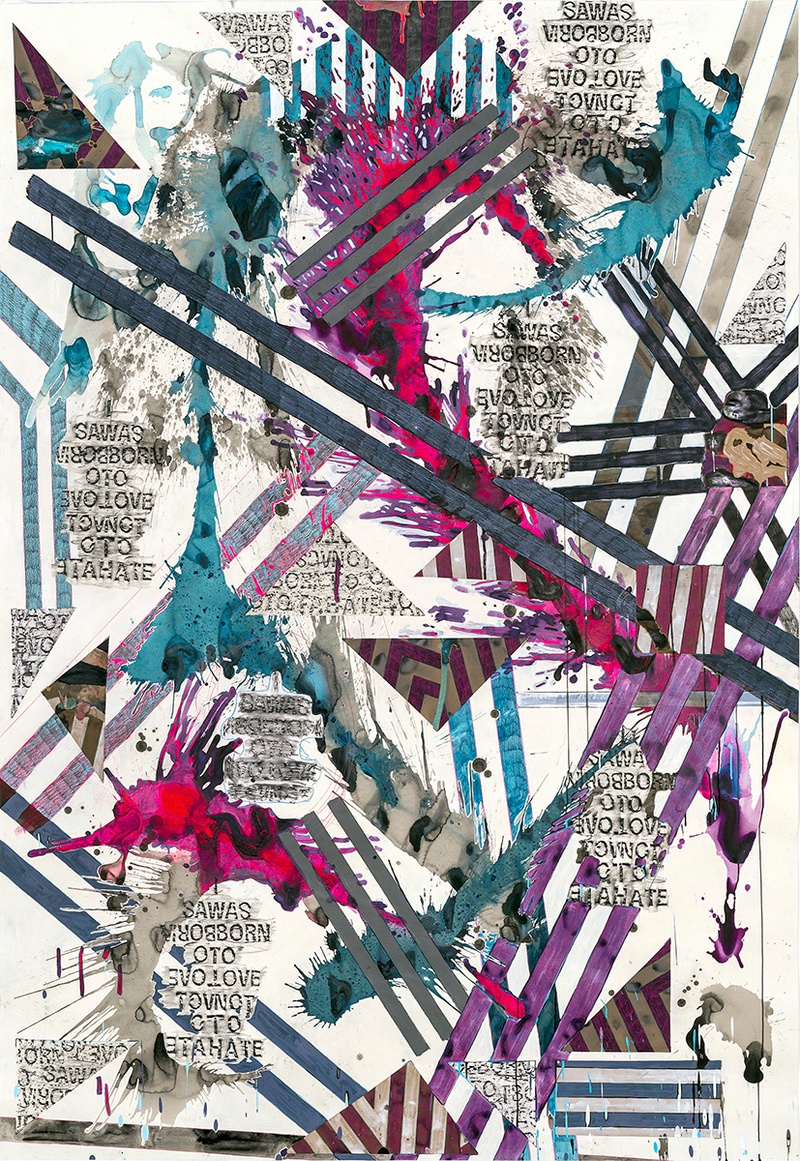

Alexandra Grant, Antigone 3000 (4), 2018, Collage, wax rubbing, acrylic paint and ink, sumi ink and colored pencil on paper

Positioning failure as something important leads to the best kind of growth. When you talk about things at a more holistic level and look at psychology, it’s the integration of the shadow into our lived experience that makes us mature human beings. As creative people, how do we integrate those periods of not being in the spotlight? Like, how do you discipline yourself when nobody is looking?

Early in my career I had a really exceptional experience. I was offered, before I had gallery representation, a show at MOCA. There was an approval process and two illustrious curators came to the studio and said, “How are you going to handle the success that’s coming?” And of course having not had success, I sort of scratched my head. I said, “Well, there’s this Sufi myth which I can’t remember specifically, but it had something to do with a magi who said that the kingdom, both when it was full of riches and when it was impoverished, had to have the same value system. That that was what was central.” So, I convinced these lovely curators that my work, and who I was, needed to be the same when everyone was looking and when no one was looking. I just sort of intuitively knew that this position would be important.

Nobody talks about the stresses of success, right? How stressful it is to have all this attention and all of these demands and not know how to navigate it. I also had moments where nobody was looking and my fake Sufi myth became very central. You know, “Alexandra, you told these people, and they believed you, that your practice had to be the same when everyone was looking and when no one was looking.” It was as though my own myth helped me understand how to be in the creative world.

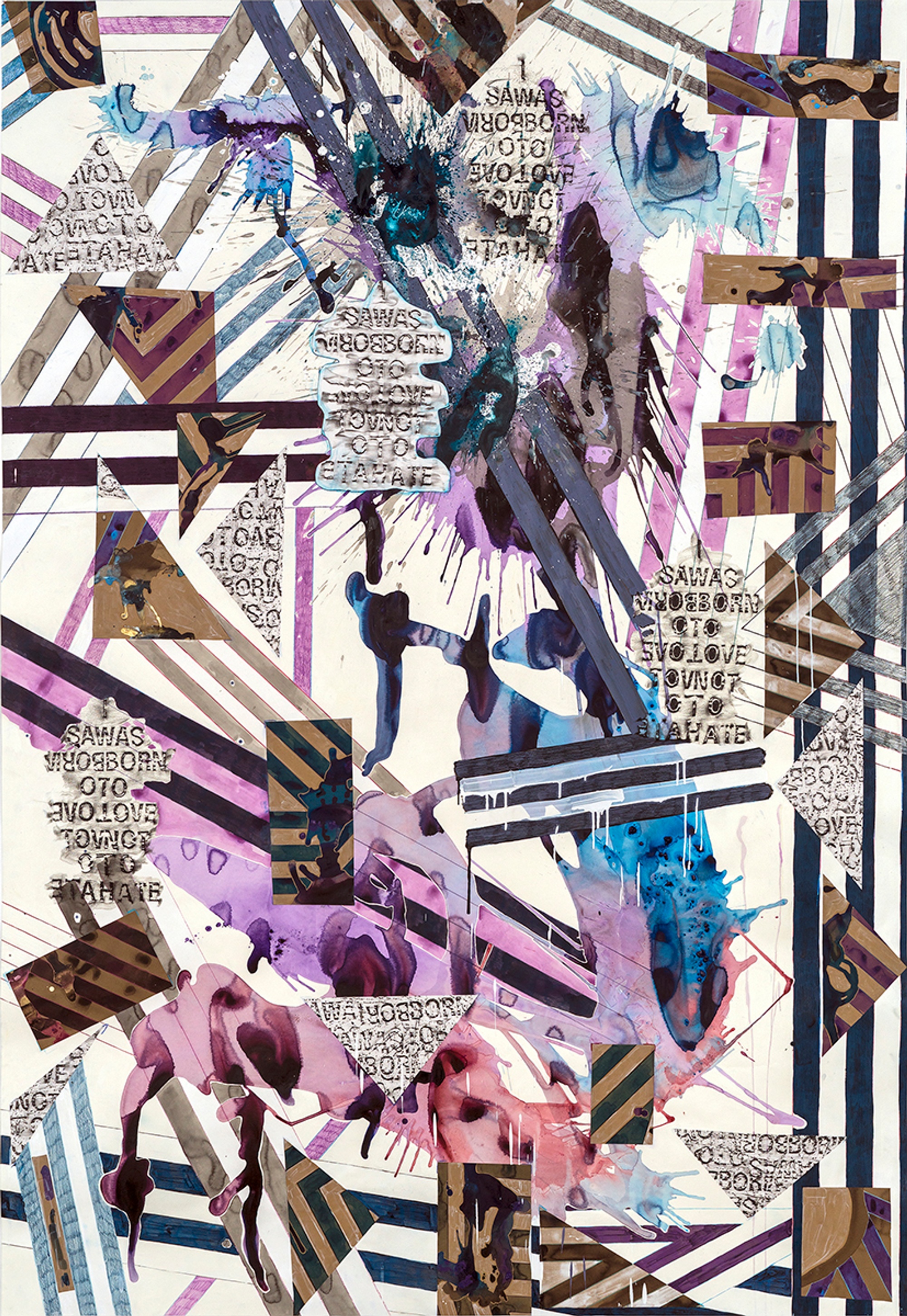

Alexandra Grant, Antigone 3000 (2), 2018, Collage, wax rubbing, acrylic paint and ink, sumi ink and colored pencil on paper

You’ve been very engaged in philanthropy and activating your cache as an artist to help empower people. Can share advice about the power of giving?

When I first moved to Los Angeles, I met an artist named Kyungmi Shin and she gave me the gift of a connection to someone who had an artist space. It was called “At the Brewery Project,” run by John O’Brien. He gave me the opportunity to curate a show. One of the rules was that I had to include my own work in it. What I really loved about this opportunity, as a person new to Los Angeles, was that I had to search for artists. It took away my passive receiver mode, which a lot of artists and creatives get into, which is, “I am just going to sit here and wait to be discovered,” and then their resentment builds. I have a lot of students who are like, “When will it happen to me?” Being given a show to curate allowed me to go out and find like-minded artists and create an environment where we could all thrive. So even though there wasn’t very much money attached, it was economic in the sense that economy’s root is “oikos” in Greek and it comes from home. It’s about creating a safe place.

What creativity really is, is being part of a community. It’s being part of a lifelong exchange with other people who are making. So, it really is philanthropy for the love of humankind first, before we even put money into the picture. It’s creating an economy of exchange of ideas.

My parents were both educators. I attended a Quaker college and I think that the Quaker ethos was very much part of how I see communication working, valuing the voices of other people, and in the sense of working to create peace through our actions. I really believe in it.

My grantLOVE Project came from the question of, “How can I create exchanges that would benefit other artists on a small scale, but also teach?” It’s okay to make work about these exchanges and to demystify what philanthropy is. When you give a young artist $2,000—these small exchanges can really benefit the practice of an artist at a very vulnerable place in their career, or an organization where a small gift can make a big difference. What we do is make very affordable editions, whether it’s prints, jewelry, or beach towels—where people can spend a small amount of money but be part of creating something larger. Often the attention that these projects draw brings in friends even more than funds. It’s using art as a way of talking about storytelling. It’s an alchemy, where a gesture and artwork can become something that’s very significant. I think one of the things that’s happened, and it’s very confusing for younger artists, is that that the level of money involved in the high end of the art world is so large. You hear a painting sold for $150 million and you can’t pay your rent, and yet you’re somehow in the same rodeo. How is that possible? So, what I enjoy is taking some of the concepts that are so abstract and making them more real and more tangible.

It’s not selling out, it’s selling up. Love is very central to your grantLOVE Project. You hold that word close as a driver for your work and life.

Well, I love love. Even after I’ve worked with the concept of it for over a decade, I only publicly defined what it means to me this year.

What is it?

It’s a three-pronged definition. The first part of it is self love. I don’t think that we can truly help other people until we’ve worked on our own healing, or else we are going to keep promoting inherited or naturalized belief systems that aren’t useful within the work we do. Self love is the first step to being able to love others. The second is really just that sense of loving other people in our community, doing more than maybe we’re comfortable doing. But it has to come from a place of self-healing first. The third is loving the responsibility we have to love others who are different than we are. Politics and business thrive from creating false differences between us. I think that we really are in a time where we need to love those who are different than we are, and take action and responsibility towards that.

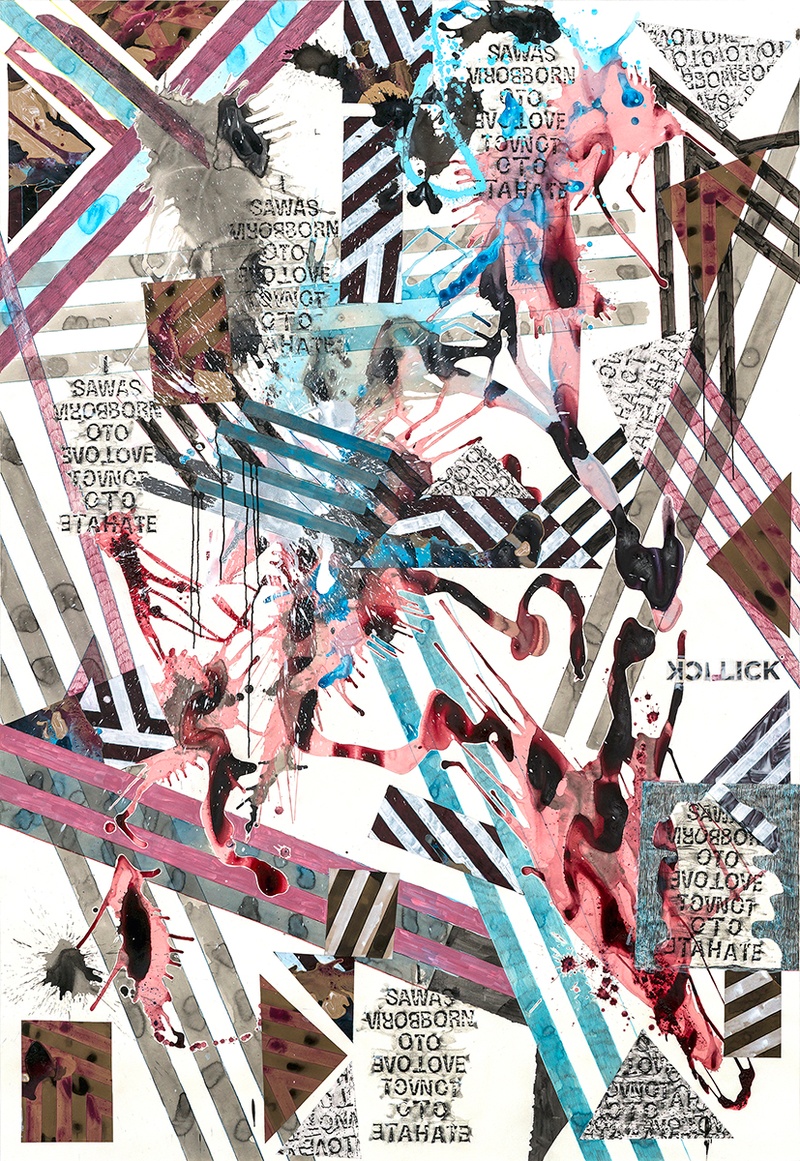

Alexandra Grant, Antigone 3000 (1), 2018, Collage, wax rubbing, acrylic paint and ink, sumi ink and colored pencil on paper

All images courtesy of Lowell Ryan Projects.

Alexandra Grant Recommends:

Psychomagic: The Transformative Power of Shamanic Psychotherapy by Alejandro Jodorosky

Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing by Hélène Cixous

Shoah by Claude Lanzmann

The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa

We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo

- Name

- Alexandra Grant

- Vocation

- Artist, Publisher, Philanthropist

Some Things

Pagination