As told to Hether Fortune, 2493 words.

Tags: Fashion, Art, Inspiration, Beginnings, Identity, Success, Politics, Money.

On evolving a DIY art project into a sustainable business

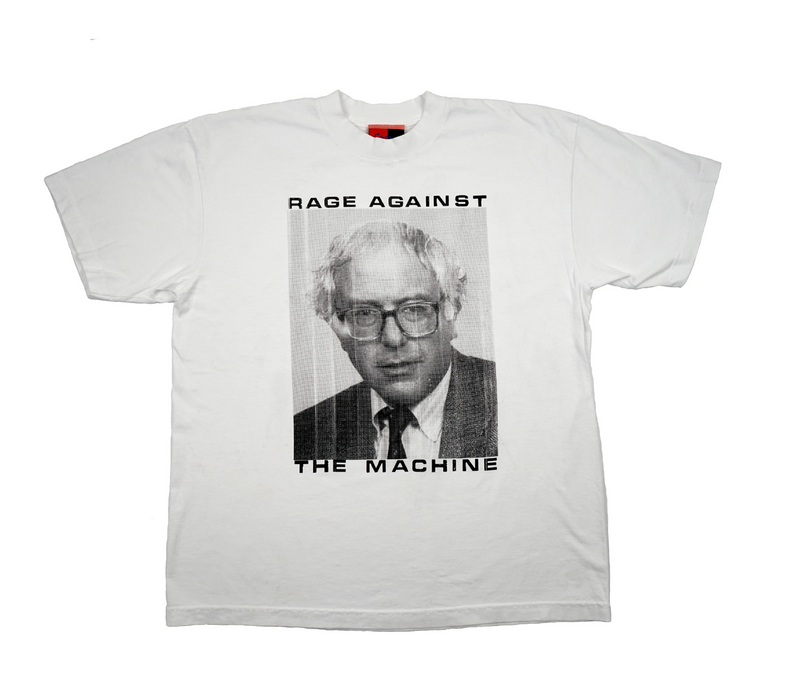

Artist and designer Sonya Sombreuil of COME TEES on the surprising popularity of her Bernie Sanders shirts, knowing when it’s right to mix politics with your creative and professional life, and the slow process of learning to value your own time, energy, and ideas.There’s been so much interest in your Bernie Sanders shirts. Were you surprised?

I had no idea the volume of orders that would come in. I’ve never handled my business on this scale, so I had to learn how. I mean, the infrastructure is there, but a lot of things had to change. I thought I was going to sell 100 shirts, maybe. It’s been incredible. I didn’t realize how uninformed my relationship is to money. When I think about cost, I just think about the cost of the product, I almost never think about the labor. So I was kind of blown away at the cost of the shirt if you incorporate all the labor. And when I thought about how I was going to pay people, it had never dawned on me that the money gets taxed in every transaction. It doesn’t just get taxed once. It’s not just your income that gets taxed. Every time it changes hands, it’s taxed. Somehow that had never dawned on me.

I mean, maybe because you’re not usually working with large sums of money and huge volumes of output. It’s like, why would you have to think about that? I’ve never thought about that.

It’s been like a thought experiment or something. I’ve engaged a little think tank around it. The Bernie Sanders campaign is unique in this way that no person or organization can donate more than $5,000. So when they talk about being fueled by small donations, they really mean it. That is what is sealing it against any special interests.

Have you been able to take a percentage [of the money you’ve made selling shirts in support of Bernie Sanders] to cover the cost of the labor, or do you not feel good about doing that?

Yeah, I mean, I have to. I don’t have enough money in my business to make that kind of contribution. I’m not profiting, though.

In a very limited way I’ve done philanthropic work with my brand from the beginning, and I never realized that it was okay to withhold the actual cost. I would be like, “Well, the $700 cost of the shirts, and printing them myself, that together will be my donation.” It’s kind of like a guilty-conscience style of working. Now I realize that was totally stupid. It would’ve been totally appropriate for me to just make sure my costs were met.

A lot of artists from a DIY/punk background struggle with this, I think. There is a certain set of morals or ethics for how we do work and how we treat each other, but we tend to not be very good about how we treat ourselves, especially regarding the compensation we deserve for our labor. It takes a long time to figure out how to value yourself and your contributions to your community. To say, “Not only is it important to give, share, and uplift but also to receive that same support in return, not just from others but from myself.”

If you did an ethnography about the punk scene, there are probably psychological reasons why people in that world don’t feel like they deserve things, or that they feel they’re rejecting the normative concept of status. But on the other side of that, maturing, aging, starting to value security… it’s been a big hurdle for me to get to a place where I think about my own solvency and worth. I’m not sure how much of this is real, but I have been, in a way, emerging from the punk or DIY scene for a long time, and I’ve felt policed by that. Maybe that is just a projection.

You’ve experienced that sort of celebrity culture crossover via your work being worn by Rihanna, collaborating with Kanye West, etc. I imagine that there must have been some scene shade to navigate or weirdness for you, being that you come from such an underground world of artists.

I think a lot of it is my own projection, and in fact, mostly I have felt totally buoyed up from my community. It’s really important to me to still be contributing to and engaging with that world. Any shade I’ve received has been so slight, but I felt it profoundly because of those values that I had internalized. When Rihanna randomly got in touch and wanted to wear my work, I was literally sleeping in a sleeping bag on the floor of my studio. And I continued to afterward! [laughs] So yeah, I haven’t really felt like I’ve been thrown a lot of shade but I’ve definitely felt guilty about coming out of that scene and having to change my price structure, which is totally based on reality and not on greed. But learning to ask for what you need is a skill that I hadn’t been instructed on and I’m having to learn now. It’s something I still struggle with and it’s sort of self-perpetuating because I think a lot of it is about what image you project and how. And it’s also about language. It’s really easy when you’re interfacing with other entities to get the message reflected back to you that you aren’t worth anything, monetarily.

I think it has everything to do with the way capitalism is structured to not value artists, to just take from them. They’re often the last people to get paid and the last people to get acknowledged.

Right. Unless you can be a vehicle for corporate messaging. But I think that we’re all on a spectrum that is generational. I meet a lot of younger people who just want to get paid and sometimes when I talk to them I’ll have like… a spasm. It’s funny to me. Like some kind of reflex when I hear that. I think that’s the right attitude to have, but it’s so funny to me because I’m from the old school where you think you should work for free forever, that you should just be grateful to be in such a privileged position wherein you get to make art at all. But that’s not correct.

It’s a myth we’ve been sold in order to keep us down and keep us from thinking critically about where the money’s really going and what’s really happening. This mindset of “we don’t deserve money, but it’s fine for all the money that we could potentially be getting, using, and investing back into our communities, and into each other, and into building things that we want, that matter to us, to our friends, to our families, to our communities to go instead to these corporations who are destroying the world.” And somehow that’s okay? That’s more “punk?”

What made you want to make the Bernie shirt? What makes jumping into the fray of politics with your brand feel like the right thing to do at this particular moment?

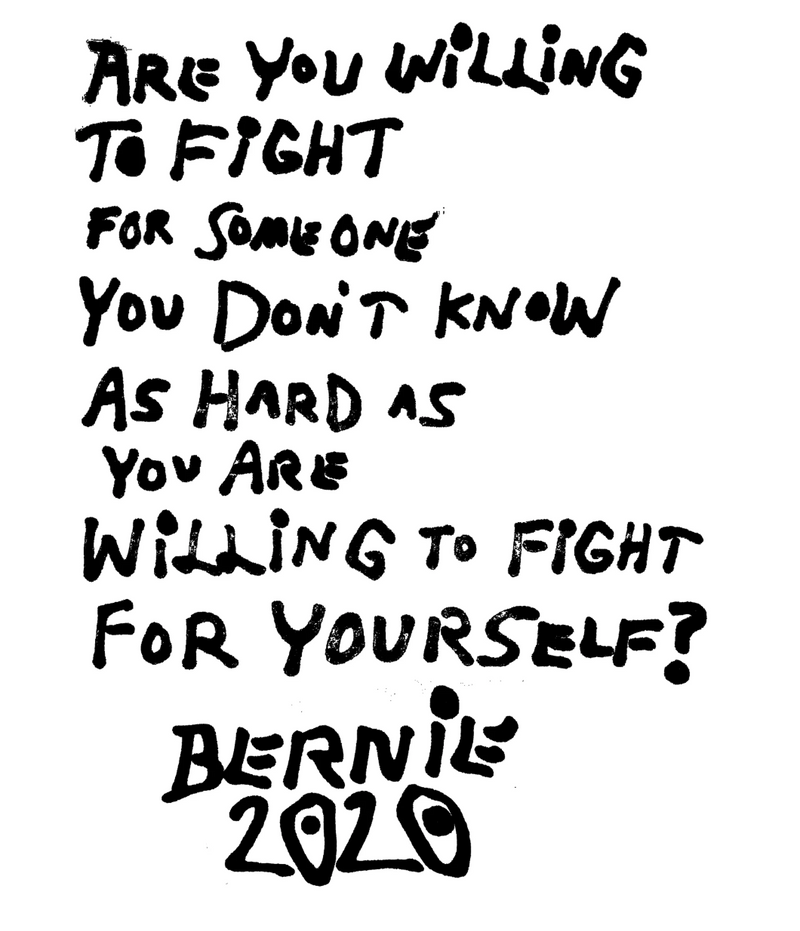

First of all, you can spend your entire life responding to issues on Instagram and we all know it’s like yelling into an echo chamber or whatever. Instagram is a space I use for commerce, therefore anything that I say in that space is a reflection of my brand, and I always found that to be kind of gauche, like virtue signaling or whatever. I am also a bit confused about the ethics of a public figure or brand giving political endorsements. The Bernie Sanders campaign exists socially and culturally outside of this essential mandate and I had a really negative reaction to the way it existed in culture at first. Then, as I got more informed and started to experience it as a movement, it gradually became a profound experience for me.

I never, ever, ever thought it would be possible in my lifetime to find someone in the arena of electoral politics who reflected my values and who is experienced in creating reform. So when I started to feel the conductivity and warmth of this volunteer movement, I felt like it was incumbent on me to say something. But I also have a lot of friends who, because of where their identity falls on the political spectrum, don’t fuck with it at all. So stating that I’m still invested in this system even though most people know, on a visceral level, that it’s complete bullshit, made me feel weird. And it’s not lost on me that there are friends I talk to about it and friends I don’t talk to about it, who I keep some of these thoughts and opinions private from. And it’s sort of hilarious because obviously it does end up being also propaganda for my business. Someone said that to me today, that it earns a lot of good will for what I do, but I didn’t anticipate that at all. I just felt morally obligated to say, “This is a crisis, and there is a window of opportunity here and we need to act on it.”

I feel that for many people, and for many people I love, my participation in electoral politics is viewed as a form of complicity. It shows that I am still invested in what is potentially a broken system that benefits very few and that I have been automatically shielded by some of the more nefarious aspects of this system.

I remember when you were starting to pop off in LA and it was such a fresh approach to being in the art/music world, because it was almost like you were making wearable zines or something. It wasn’t a thing that many people were doing before you started doing it. And now that style and approach to fashion is very much a thing. You were at the forefront of this very particular wearable art/punk movement. A lot of times the people who pull culture forward don’t really get the credit they deserve, or get to have a sustainable trajectory or career. But you’ve stayed very visible, steadily rising and growing. What has that looked like to you? What has it been like for you building a career for yourself from this genre that you kind of created?

I don’t think I created it, but it’s like there was some level of prescience there—like unconsciously I was on the early tip of a wave. I was so creatively isolated before I moved to LA. I feel like I’m sort of old but still having to learn a lot of things other people figured out when they were much younger. But one of the benefits of having been living in a really small scene without social media and without an audience is that my work ethic and my values got really baked in. So, in that way, I have the ultimate resource, which is that I understand my own work and how the aesthetics have evolved, and the ethos of it is enduring. And I think it’s something that people can feel, as opposed to just sort of…

Like flash-in-the-pan branding.

Yeah. Or things that are kind of like a composite of other things that are incredibly topical and ephemeral. I feel really in touch with myself and that’s a by-product of having existed without an audience for so long. But the hardship of this is that I work really hard and haven’t seen a lot of the successes other peers have. I’m so grateful for everything that I do, but I see the ways that other people are entrepreneurial or know how to work the system better than I do. And so I sort of wish I knew more about that. On one hand, I feel lucky because I have had a sustained practice. On the other hand, I see people who are smart about the resources that are out there and I sort of feel like I’m dumb about it. I’m still working stupid, as they say, you know?

Don’t worry—you’re not alone. [laughs]

Even with this Bernie Sanders thing, I learned something where I was like, “Oh, I’m engaging an audience that exists outside of myself.” But my whole thing has been slowly and assiduously adding people to a really small audience. My message is made to relate to a really small audience. It’s been a huge joy, but it’s also made it hard for me to monetize what I do and expand the scale of what I can do.

When you started doing COME TEES did you imagine it could ever be a sustainable long-term project?

Well, I mean It’s been 10 years that I’ve used the name COME TEES. The name and concept was kind of a joke at first, but I just incorporated this year and hired a small group of people. I’d been functioning like a studio artist, so it was almost like a moniker and less of a business until recently. So no, I definitely did not foresee the sustainability of it. I’ve been very focused on who I am and my relationships but I haven’t been that intentional about my path and the bigger picture. But I want that to change. I’ve always just put one foot in front of the other. I’m so fortunate that I was able to push it this far.

It seems like your relationship to your work is changing, so you’re on your way.

Totally. But it’s incremental. I had no experience inside my industry when I started. The only experience I’ve ever had is as a creative and studio artist. So, it’s been about learning tiny new tricks as I’ve gone along, but it’s been really cool. And you know, once in awhile I have one of those moments, that weird feeling, it’s almost like a bodily feeling of excitement, like particles that are vibrating. Where I’ll think like, “Oh, I know what I want, I know where I’m going,” or “I know where I want to take it.” It’s like having a vision, but it’s always very momentary.

Sonya Sombreuil Recommends:

-

The writing of Sarah Schulman, particularly her book Conflict is Not Abuse, but also Gentrification of the Mind.

-

I’ve been revisiting RATM “Battle of Los Angeles” a lot right now… still so fresh.

-

The films of Ashgar Farhadi. I have a personal fixation on a concept I call “mercy”—mercy of the filmmaker on the subjects of the film, and mercy toward the audience. Farhadi’s films are uncomfortable and deal with intractable conflict, but they are also humane and merciful.

-

The podcast Citations Needed

-

I’ve become obsessed with making my own yogurt. So simple and yet miraculous…

-

Ebay. Forever and ever.