On sharing the magic of the creative process

Prelude

Serbest Salih is a photographer from Kobanî, Syria. He is the the Director of Sirkhane Darkroom, a non-profit mobile darkroom and photo lab dedicated to teaching children from Syria, Turkey, and Iraq how to shoot, develop, and print their own photos. By encouraging a new way of thinking and seeing through photography, Sirkhane students have the chance to remain playful while sparking their imagination—the resulting photos are ones of happiness, light, and hope. The darkroom operates in the south-east of Turkey, a few kilometers from the Syrian border.

Conversation

On sharing the magic of the creative process

Artist and educator Serbest Salih discusses how he started his mobile darkroom and photo lab and why he finds inspiration in teaching children from Syria, Turkey, and Iraq photography.

As told to Alex Westfall, 2173 words.

Tags: Photography, Education, Process, Inspiration, Multi-tasking, Collaboration.

When you see the images made by your students, how do they make you feel?

The images are the reasons that I’m continuing this process, this journey. It always motivates me when I see the result. Our program lasts about four weeks. In the beginning, the children are very shy, they don’t participate. By the end, they start speaking about themselves, expressing themselves. You see the improvement in their photography. So, it’s always a source of inspiration for me.

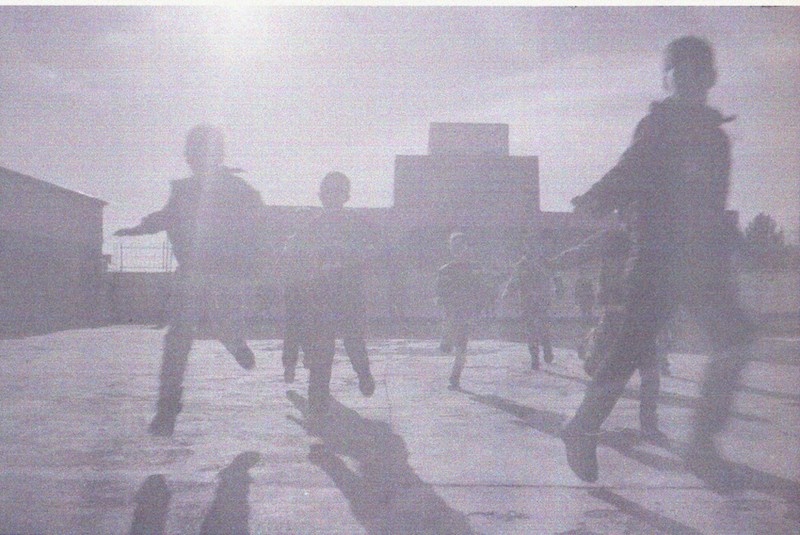

I remember one child tried to capture a photo from an animal’s perspective. He laid down and tried to capture his friend, trying to see the world from the eyes of other creatures, animals. They are capturing the true moments of human lives and they see so differently. They see the world from different levels. It’s a very innocent perspective because it’s without editing—it is a free moment without any pressure. When they see any moment that inspires them, they capture it. Their work is about the celebration of childhood; about seeing the world through the eyes of children, not as adults.

When I teach them photography composition, I don’t tell them what they should do. I tell them that photography doesn’t have rules—that when you shoot, you just have to feel it. I try to make sure not to pressure them. [Even though] it’s analog photography, and it’s a limited [medium], I tell them, “You have just to feel it, you can shoot whatever you want.”

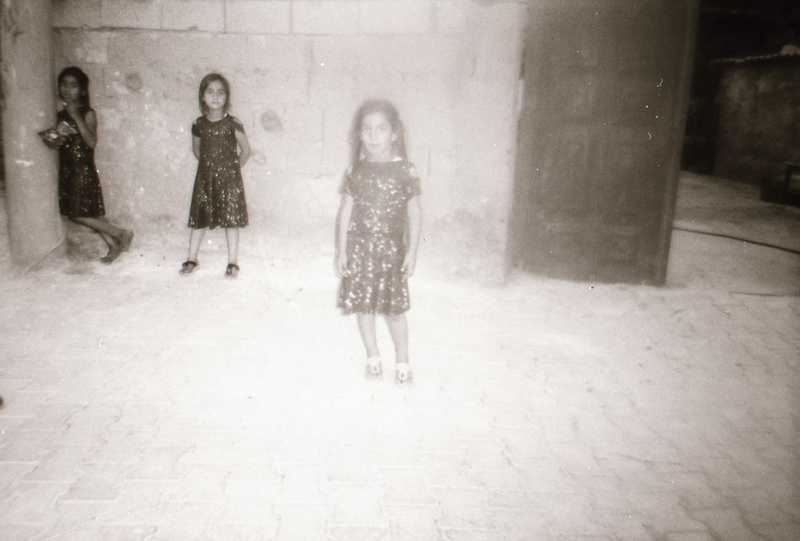

One of the main purposes of this project is to make children participate in the entire photographic process. When we make photo books or exhibitions, the work is all selected and titled by the children. I don’t want any adults to select what any child wants to shoot. [Our program] gives them this space to let them speak for themselves. Their work shows true moments of what it means to be a child, or a refugee, or a person in need. We usually see in the media a different perspective.

I see in some pictures that your students really love shadows, figures in the landscape. In a lot of the photos, I’ve noticed that the students like to make hearts with their hands.

It’s something they like to do. They show the heart to each other, and it’s especially inspiring when the heart is made by kids from different backgrounds. Because now they are together and this heart represents moving past all the hate speech, or anti-refugee situations. You see hope in these hands that form the heart [shape].

Sultan, 14 years old, Nusaybin, Turkey

You’ve previously spoken about how photography unites people when we’re lost for words. It’s also a way for young people to build and understand their own perspectives and positions in the world through their vision.

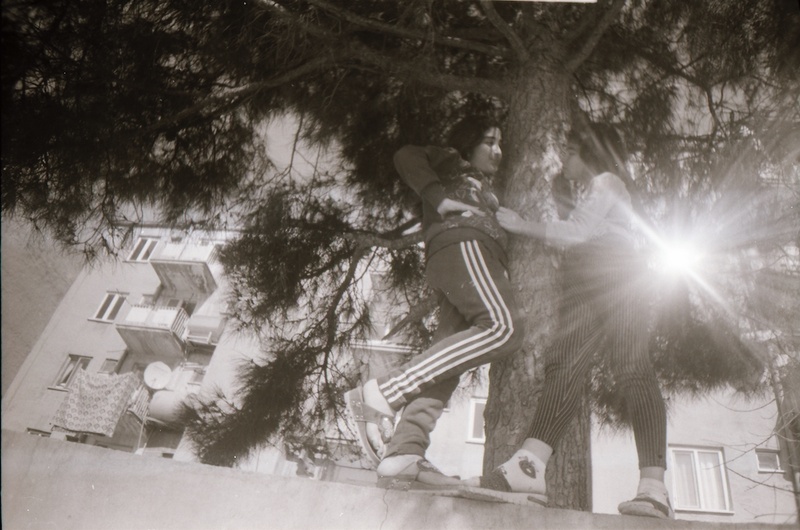

One of the reasons I chose to use photography is to bring together children from different communities and backgrounds. We see here that people are actually speaking the same languages, but they never get the chance to communicate with each other. That’s why we use photography, because it’s a universal language.

When the children go outside to shoot, I try to put one Turkish child and one Syrian child beside each other to help each other, because I want them to get integrated, and use an alternative way of communication—photography—to bring them together. For example, in the last workshop, there were two children who were neighbors, but they never communicated with each other. It was their first time meeting each other in this class, where they learned new things about each other. They became best friends!

What does a typical workshop look like?

The first week is about letting children get to know each other, playing introducing games. After children start to get warm and socialize, they write their own rules and agreements [for the duration of the workshop], because we will spend one or two months together. Here, it’s very difficult to be a child. Most of the children are forced to grow up fast. So I fuse photography composition lessons with awareness workshops about child rights—[topics like] bullying, child marriage, child labor, that gender is not a barrier.

Then I show them all different types of cameras—digital cameras, analog cameras, pinhole cameras. I explain to them why I selected analog photography—because you have to start from zero if you want to learn photography. I also show all different types of photos from all around the world…for example, Vivian Maier. They usually always see male photographers, I’m also trying to connect [her work] with gender [issues]. I show them some local photographers like Erdem Varol.

Then I give them a very simple compact camera. They take it home for a week or two. After they finish shooting photos, they come back to the workshop. I show them how to develop their film and how to print inside the darkroom. You put negatives inside the enlarger and you put the photo paper down. The first time they see the image show up on [the photo paper] and in the chemicals, it’s like magic for them. They start yelling, Oh my god, oh my god, how could this happen? But, with time, they start to understand, it starts to make sense. They start doing the entire process all by themselves. I’m just watching them go, standing beside them.

Alican, 10 years old

When you first came to photography, did you see it as magic, too?

I started photography when the Syrian War started. I was about 20 years old, so it’s been eight or nine years. I’m also a refugee from Kobanî, Syria, a town on the Syrian-Turkish border. For me, photography was a natural way of communication. After the war started, I came to Turkey as a refugee. In the beginning, I couldn’t speak Turkish, so I used photography to express myself. Then I started working with some NGOs as a photographer and one day, I got the chance to meet Sirkhane and I started working as a volunteer… it inspired me to see [the children] use art as a language. This is how the story started.

You have your own artistic practice while devoting your energy and time to developing the artistic processes of these young students. How do you make time and energy for your own work?

Right now, I’m a little bit away from my own work, and I’m okay with that. For me, it feels like I’m continuing photography by educating children in art, so that they can continue [their own] photography. It’s been almost one year since I’ve worked on my other projects, but I feel very comfortable because I’m still inspired every day. I consider my work with Sirkhane as part of my artistic process. What motivates me to continue my own photography are the photos taken by children. In their photos, they are analyzing the world from their own perspective—from out there, from up, from down, from behind. They give me new ideas, too.

Do you have advice for people who are looking to educate young artists?

The most important thing is not to set the rules. Let children be involved in all parts of the educational process because they will shape it. They really will.

In Los Angeles, I work with a photography non-profit for girls ages 13 to 18. When I spend time with my students, they’re expecting me to teach them things, but I often feel like I am the one learning everything by seeing the world through their eyes.

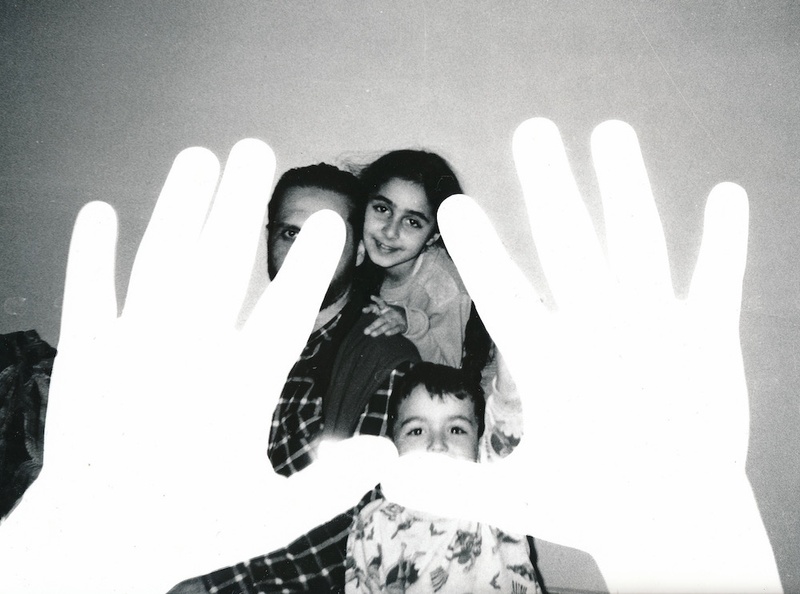

I tell [my students], “You don’t have to call me ‘Teacher.’ You can say my name because we are the same.” It doesn’t matter if I’m an adult or a child because we are the same. Maybe we look different. But I want to show them I am a friend. I’m always learning new things from my students. One eight-year-old girl named Dua really inspired me. She fused negative printing and photograms together. That was really amazing to see. Do you know anything about photograms?

Is it almost like a cyanotype, no?

It’s a way of printing in the darkroom where you put materials directly on the paper. Dua brought her negatives, and she printed them in the darkroom. While she was printing, she put her hands right on the paper. It was really amazing to see the kids already thinking of alternative ways of printing.

Dua, 8 years old

I’m sure you and your program have completely shifted the way that people in the community see photography too and maybe even its political power.

At first, sometimes parents don’t believe in the program. They think, Oh, just let us send our children there so we can spend time on our own. We sometimes invite families to watch us for one day; to see how we are taking children very seriously. When they see their child starting to speak inside the workshops, they start to believe in us. When the children print photos inside the darkroom, they go home and show them to their parents, who sometimes call me and thank me for the result, and about the development improvement of their child.

You frequently collaborate with publishers and exhibition spaces. How does it feel knowing that your students’ work is being seen by so many people?

As refugees, we cannot go out, but all around the world—in the media, or in galleries—they are showing our world. They are representing our project. It’s a very important moment for me and for the children to see their work in different places outside of Turkey.

What are your dreams for Sirkhane’s future?

Elif, 10 years old, ‘I wanted to take a selfie in a different way. I wanted it to be something that belongs to me.’

A few months ago, I had one interview with a child about what he thought about Sirkhane. He told me, “When I grow up, I want to do your work because it’s really made more people happy.” Now, some of my first students are adults that are continuing their education in photography. My plan for the future is to also let them get involved with this educational process. I want to let older participants teach new children, so that it’ll be a tree of communication.

Also, because we are a non-profit project, we are in need of materials, second-hand cameras, and film. Turkey is under an economic crisis, so materials are expensive. I hope to make [our work] more sustainable because now, film photography is super expensive. I am trying to find ways for us at Sirkhane Darkroom to create our own black-and-white film stock. Now, I’m making studies—having some connections with museums—that are supporting me with this big goal.

How do you manage running the entire program on your own?

Sometimes we have our finance and logistics team supporting me. But preparing for the workshop, I do this by myself. Sometimes, I welcome volunteers to be part of this project, especially artists because I want the children to learn new things—different perspectives from different people, not just me. But I love my work. I’ve been working all seven days. My colleagues and friends say, “Serbest, please don’t work too hard,” but I love my job—I wake up very early [for it]. Work hours begin at 8:30, but I come in at 7.

I know that feeling… where it doesn’t feel like work at a certain point, but life, free time, passion. That’s how you know you really love what you do.

It’s a chosen job for me. It’s a perfect job for me.

Shirin, 16 years old, from Kobanî, Syria

Aya, 11 years old, from Qamishli, Syria

Jiyan, 14 years old

Melik, 13 years old

Eylem, 13 years old, from Mardin turkey

Ahmed, 10 years old, from Al-Hasakah, Syria

Serbest Salih Recommends:

Soukura by Alsarah & The Nubatones

Infinite Identities: Photography in the Age of Sharing

Erdem Varol‘s photos

Brendan Barry’s photographic constructions

C/O in Berlin

- Name

- Serbest Salih

- Vocation

- artist, educator, director of Sirkhane Darkroom

Some Things

Pagination