On the boundlessness of art

Prelude

Perry Chen is an artist and the founder of Kickstarter. He approaches his work with an openness to form and context, having used art to explore technology, and technology to help democratize the funding of creative work. His studio practice often explores how we negotiate a world of growing complexity and uncertainty, using research and archival material as entry points for engagement.

He is known for his engagement around the problems of profit-centric systems; specifically the need for better structures, tools, and institutions to enable a more generative and less extractive society. In 2018, he was honored by The Center for Democracy & Technology for his commitment “to shaping a world where the internet and technology improve lives and propel human creativity.

His solo exhibition, Perpetual Novelty, opened at Nature Morte in January 2021, and can be viewed here.

Conversation

On the boundlessness of art

Artist and Kickstarter founder Perry Chen on creating new spaces online and in the world, not being afraid to be a beginner, the problem that led him to invent Kickstarter, his recent solo art exhibition, and how the different things you make are connected.

As told to Brandon Stosuy, 3129 words.

Tags: Art, Technology, Inspiration, Process, Business, Multi-tasking, Independence.

When you started Kickstarter you were a musician trying to solve a problem. We’re talking today because you’re finalizing a solo art exhibition. Do you see yourself as an artist, a musician, an inventor? Do you try to avoid these kinds of labels?

Right, I was trying to solve a problem. It was my problem, but it was also the problem of a lot of creative people I knew. How do you get the money to make the things in your head? Especially when they are not business ideas, but projects with uncertain business prospects. You have an idea. That idea may need some money to bring it to life, even if you’re working cheaply. How do you get the money to actualize the ideas that speak deeply to you? The ones that would pain you to let go of, and where money truly is the barrier.

In terms of labels, I’ve been asked if Kickstarter is itself a social practice artwork, but I’ve found this kind of “What is art?” question less and less helpful to my own understanding of my work. What I can say is that I approach my work as an artist. Which, for me personally, means a mindset of experimentation, an openness to form and context — and an unboundedness from the strictures of other fields.

I’ve moved through a variety of creative realms. My first love was music, growing up in New York City in the midst of hip-hop’s rise in the ‘80s and early ‘90s. In my late teens, I discovered Drum n Bass, and started DJing around New Orleans, where I went to college. From there it was like, “Whoa, who are these people making this music? Maybe I can make this music, too.” So I learned how to make music on my computer, and focused on that for a few years in the early 2000s.

I didn’t have any sense of conceptual artwork or any of these other things that I now understand. But I was always drawn to creating things. Once I understood the freedom of conceptual artwork, I did some of my first non-music works. Then I detoured to work on Kickstarter for like a decade. Every time I was interested in something, I would try to figure it out. I had zero tech or office-type work experience when I started working on Kickstarter.

When I started working on Kickstarter, I stopped making music. At that time, the electronic music world was still in strict boxes: “This is how house sounds. This is how techno sounds. You’re using the wrong snare sound for Drum n Bass.” Even though there was always experimentation and people pushing the boundaries, the boundaries were very clear. It felt limiting.

Since then, the genre walls have fallen down. I’m so happy for this generation of musicians — you can feel more open to just make what’s in your head without thinking so much about, “Does this now make it dubstep? Does that have implications?” It feels like a golden era for more pure creativity and composition.

The floodgates are open for what’s considered art as well. And I think that this unboundness for music and visual art has been a very good thing.

Where boundaries were hard for me to negotiate with music-making, when I thought up Kickstarter, I saw a creative space, and it all felt like clay to me. I didn’t want to feel constrained or satisfied by how things were being done in tech. I wasn’t a tech-world person. I didn’t want to be limited by the genre, if you will. And so there are many ways that Kickstarter is setup differently than other companies that came before and after it.

Sometimes the challenge is to engage with your own ideas and to follow them through to the end — because it can be dirty and mucky and complicated. To do that well, and to honor them, I think you need to be unbounded in your thinking.

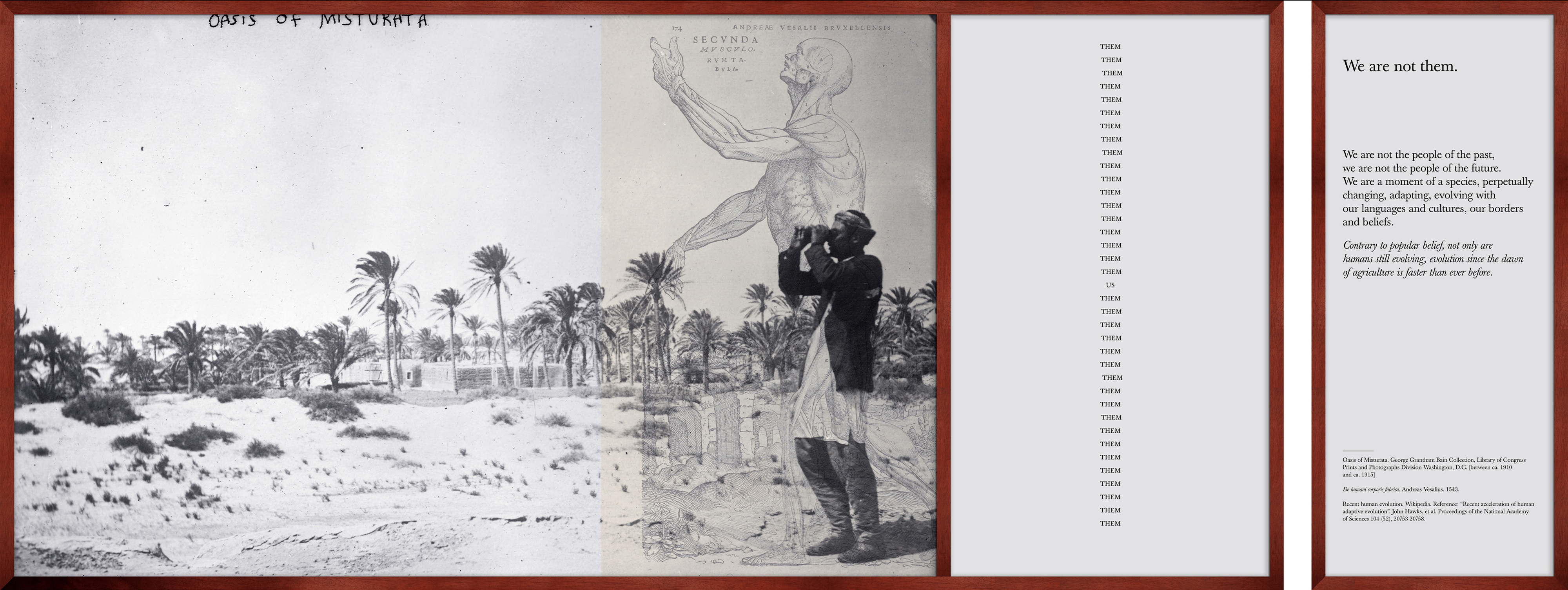

We are not them, 2020, Digital Prints on Hahnemühle Photorag Paper and Tempered Glass

Being interested in something and just diving in and figuring it out resonates with me. When I was a teenager I started a zine. I didn’t even know how to pronounce the word zine. I thought it rhymed with “pine” because that’s the way it was spelled, but I thought, “I’m going to start one.” It taught me how to write and led me down that path where I started organizing events. I didn’t know the word curator at that point either. I just started putting things together. In both instances, it was a pure, sincere interest that guided me and I figured it out along the way. Your art involves a lot of research. Is that connected to the idea of figuring things out?

I see projects like my new show Perpetual Novelty as investigations. I’m trying to understand the world better through the development of the work itself. I wouldn’t be drawn to develop a project if I’m finding easy answers to my questions. As a result, I find myself exploring areas that require a decent amount of research, even just to find a footing into better questions.

I read this quote recently, by Kevin Kelly, that resonated with me: “Answers are becoming cheap; they’re almost free, and I think what becomes scarce in this kind of place that we’re headed to is questions, a really good question, because a really good question can unleash new questions.”

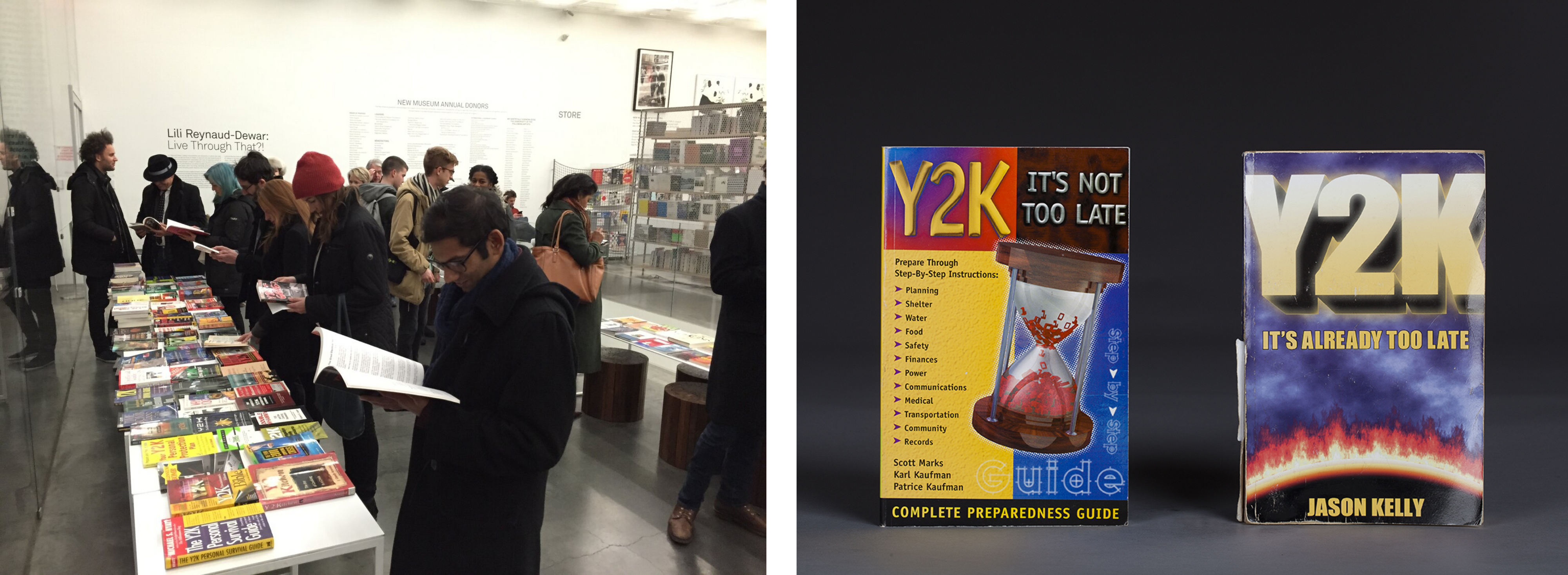

My project, Computers in Crisis (2014), was an investigation where I was drawn to the phenomena of the Y2K crisis through the number of books that had been published around the topic in the years leading up to the millennium. As I dug in, I found many aspects of the Y2K phenomena that felt important; such as the implications of the global effort to deal with Y2K for our ability to deal with global challenges like Covid and climate change; and the failure of leaving Y2K largely unexamined because we have pigeon-holed Y2K as solely the sensationalism that surrounded it.

For a project like Perpetual Novelty I started with a question: How do we negotiate a world of growing complexity and uncertainty? After a few months of research, I start to try and distill and improve my nascent understanding through artmaking. I’m a visual thinker. So, through this process of visual formalization, I’m both getting a better feel for the ideas I’m grappling with, and I’m creating entry points for engagement by others.

And this process of going from research to artmaking forces me to examine, “What is the essence of what I’m working on?” And how do I represent or embody that essence?

We cannot plan what cannot be predicted, 2020, Digital Prints on Hahnemühle Photorag Paper and Tempered Glass

What did you learn in your investigation into the question of “How do we negotiate a world of growing complexity and uncertainty”?

The name of the show, Perpetual Novelty, comes from the scientist John H. Holland who did pioneering work studying complex adaptive systems, which are the systems that make up our world — ecosystems, cells, economies, cultural and social systems, the internet, pretty much everything. A key characteristic of complex adaptive systems is, literally, perpetual novelty. The idea is that complex adaptive systems not only produce novel emergent behavior, but that such emergent behavior is inherently unpredictable. So, for example, you can know 10 people extremely well, but you cannot predict the emergent behavior when you put those 10 people together. Their emergent group behavior is that of a complex adaptive system.

As humans we desire control, we desire predictability. But these things are largely illusory. So our thinking needs to adapt to fit some fundamental truth about how the world works — as just a big bundle of countless complex adaptive systems.

Complex system scientists Jessica Flack and Melanie Mitchell talk about the need to design systems that are adaptable and robust — like systems in nature — so they can function in a range of possible scenarios, and — critically — don’t depend on our ability to predict specific outcomes. Mathematician and scholar Nassim Nicholas Taleb similarly believes we need to create systems that he calls “anti-fragile.” And parallel computing pioneer Danny Hillis summarizes that we need long-term thinking not long-term planning. “Long-term thinking” considers the limits of predictability, whereas “long-term planning” relies on our ability to predict the future.

So I’d say this concept — long term thinking, not long-term planning — was the closest thing to an “answer” I found on this journey. However, in the six pieces I made for the show, I didn’t try to focus on answers, but rather what I felt were fundamental truths:

-

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.

-

Change is constant.

-

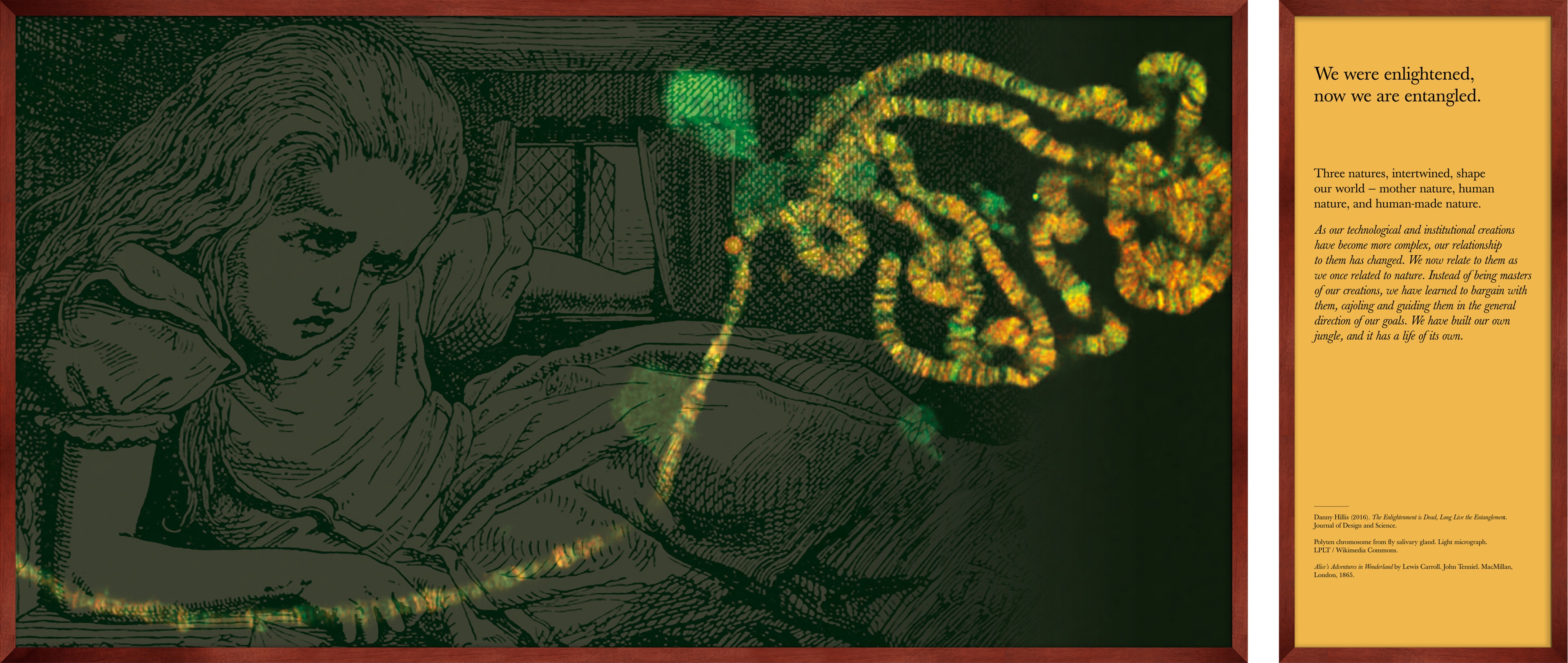

We were enlightened, now we are entangled.

-

We ain’t seen nothing yet.

-

We cannot plan what cannot be predicted

-

We are not them.

So, whatever the answer to how we deal with a world of growing complexity is, I feel like it will live within the reality of these fundamental truths. But as we discussed earlier, it’s often better questions that are most valuable. And the question that lingers on my mind now is: Can we continue to solve the problems created by man-made complexity with more man-made complexity? When I say man-made complexity, I mean science and technology as well as things like our vast legal systems. Nature has a handle on developing its complex systems over long periods of time, I’m not sure it’s the same thing with man-made complexity — the oak tree vs the US tax code, for example.

We were enlightened, now we are entangled, 2020, Digital Prints on Hahnemühle Photorag Paper and Tempered Glass

You’re interested in accessibility and making work available to people. An online exhibition can be seen by more people than if only available in a gallery setting.

You and I have talked about accessibility a bunch in the past. In general, I think the more people who can engage with a work, the better. I think that’s true of most projects, but it feels especially resonant with me as I explore some of these bigger questions, such as with Perpetual Novelty. I’m trying to provide an entry point for people to engage with these questions and ideas — one building block in a much larger conversation.

Computers in Crisis was released fully online in 2014. I released another project, Bridge to a Bad Star (2017), simultaneously as a limited edition book and an identical website for reasons of wider accessibility and engagement. Bridge to a Bad Star was heavily designed around engagement, as I collaborated with over a dozen people to investigate the events and context around the 2003 rocket explosion at the Alcântara Launch Center in Maranhão, Brazil.

Perpetual Novelty, is being released as an online exhibit first, along with six conversations that will be released in 2021 — one conversation related to each of the six works. The first episode is now live, “We ain’t seen nothing yet,” where I talk with the fabulously knowledgeable Walter Isaacson to consider how we navigate a time of immense technological change. Walter is known for his books on Steve Jobs and Einstein, and has a book out shortly on Jennifer Doudna, pioneer of CRISPR and gene editing.

So it’s about the ideas, and the form it takes comes second. It’s an exhibition now, but it could be a book later, or something else.

For this kind of project, which involves tons of research, once I feel like I have a sense of it, it often feels like I can pour this sensibility into various forms and contexts. These forms are guided by a mix of opportunities and constraints. So, with Computers in Crisis, the curators at Rhizome/New Museum were like, “Well, we are doing this series where we do online exhibits. But you can also do an event at the New Museum.” The constraints of this opportunity helped me make decisions about the formalization of the project by being like, “Okay. Great. Online and a one evening event. Now, let me take the essence of what’s resonating to me in my investigation and formalize it in a site-specific way to these constraints.” I like that challenge. It can be really fun to have just the right constraints and when molding something.

I’ve also struggled in the past to formalize certain projects when the opportunities and constraints weren’t as clear — which is generally the case at the beginning of an idea. It can feel too boundless. And that’s the other side of the boundlessness of art — the need to find or create your own constraints.

Event stills from Computers in Crisis, Perry Chen: Y2K+15, New Museum, New York. December 12, 2014.

When you started Kickstarter, what did you see it as?

It was just an idea. It was just, “I want to make this thing because I think it will work, and it’ll be a good thing to exist in the world.”

The invention of Kickstarter was of a format. Just like Instagram was initially designed as a photo plus filter plus following plus a feed. The invention was the format. Twitter was 140 characters plus following plus a feed. Kickstarter is a project idea plus rewards plus funding — if a pre-set goal is reached in a pre-set amount of time. Of course, design and experience matters, and those are part of the format as well. So I see the greater practice as format design.

Formats exist well beyond the digital. Paint on canvas is a format. Immersive theater is a format. The album is a format. The traditional school day is a format. Games are formats. Even a well-planned meal with friends is a format — which is why people often repeat and tweak those kinds of rituals. And when formats are done well they can do great things, like unlock creativity or enable generative social interactions.

So for example, my belief when starting Kickstarter was that we want to support each other — doing interesting things, doing things that we’re passionate about — it’s just that there was a lot of friction. You know, if your friend told you, they wanted to make an album, you’re probably not going to hand them a $10 bill. But the desire is there. The human desire to support somebody doing something that they’re passionate about is very real. And the format of Kickstarter was designed around allowing this to occur more easily.

Of course, design formats play to our weaknesses. But it’s worth keeping in mind that the opposite happens as well. And that formats have the power to unlock our strengths. It’s not just skill, it’s also a question of intent.

For example, I recently did a project called Significant Exchange (2020) which was a giving ritual I designed for twenty people. We asked the participants to give something significant to themselves to a stranger — another participant we paired them with. Likewise, each person would also receive something of personal significance from another participant. So their key task was to meditate on what is significant to themselves, and how they feel about giving something of significance to a stranger. There were no other rules — just show up at the time and place.

The results were extremely heartwarming. Doing the project over video, instead of in person, I was unsure of how the connections would feel. But because of the isolation of Covid, people were super eager to connect with new people. And in the end it worked even better than I had hoped.

How does all your work fit together? How is it connected?

It can take a while to see how work that can seem different on the surface connects. It takes time and reflection, connecting the dots, and seeing patterns that may not be apparent. I’ve learned a lot about myself by trying to understand what draws me to things that can seem very different.

Over time, I’ve been better able to see the common processes and subject matters that I return to. We talked about projects like Perpetual Novelty which I view as explorations / investigations; which have, so far, been focused around how we negotiate complexity. And there’s projects like Kickstarter and Significant Exchange which are formats for generative social exchange and collaboration.

And because you’re one person — everything you do informs your other efforts. The understanding I gain from one practice I carry into my other practices. I mean, how could it not?

Perry Chen Recommends:

The Overstory, by Richard Powers. A novel that will make you fall in love with trees.

Tehching Hsieh. His one-year performances stand alone.

List of cognitive biases on Wikipedia. Human irrationality, in fun list form.

Jazz Funeral for the tuba player Kerwin James. The embodiment of community and culture.

Knowing the difference b/w empathy and compassion. Empathy – the ability to understand and share the feelings of another – can also lead to bias and tribalism.

- Name

- Perry Chen

- Vocation

- Artist

Some Things

Pagination