On finding harmony

Prelude

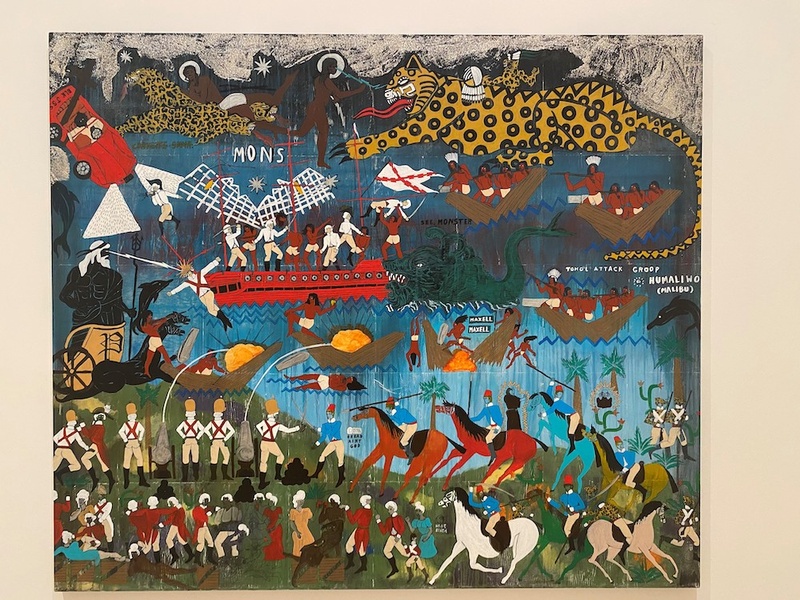

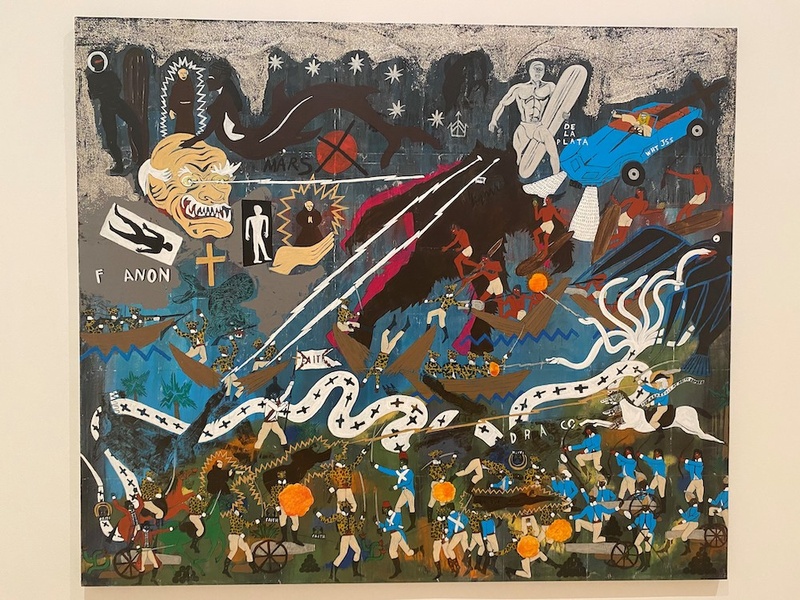

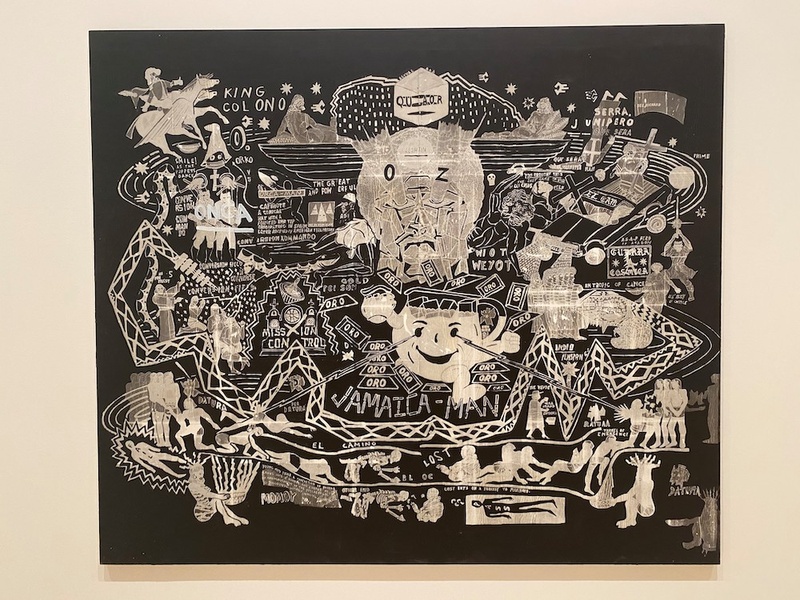

Umar Rashid’s portraits, drawings, flags, maps, battle scenes, and other artifacts continue the long history of Frengland—an ongoing project he began working on in 2006. In Rashid’s history, the dates of the Frenglish Empire (1658-1880) roughly correspond to the actual English Civil War and the abolition of slavery in Brazil respectively. Fourteen years in the making and spanning almost 140 years of Frenglish time, Rashid’s global empire has developed a complex history, much like the trajectory of actual colonial enterprises. Similarly, his work references a panoply of cultures that collapses geography and time. Stylistically, Rashid alludes to Egyptian hieroglyphs, Native American hide paintings and ledger art, Persian miniature painting, and illustrated Spanish colonial manuscripts. His world is not guided by simplistic dichotomies of white and black, master and slave, captor and captive, but challenges viewers to consider the range of humanity involved in a global empire. The lengthy, sometimes humorous, titles of Rashid’s works often reference hip-hop song lyrics, urban expressions, and current events. The artist intentionally strives to bridge the gap between contemporary popular culture and “official” history. -Ellen Caldwell

Conversation

On finding harmony

Artist and storyteller Umar Rashid on the importance of expanding the narrative, how ego-obliteration can help you evolve, and why serving others through your work is essential.

As told to Mark Frosty McNeill, 3279 words.

Tags: Art, Storytelling, Process, Identity, Inspiration.

What power do you find in narrative and was there a moment that you realized that you could create your own potent narrative?

I always tell people in the beginning, I’m a storyteller and not a painter or a sculptor. Well, I’m all these things, but a storyteller first, so narrative is very important to me in the sense that it guides everything. I don’t know who to attribute this quote to, but there’s a Russian saying to always control the narrative. And we see it play out every day in media—people wanting to own and control the narrative because let’s just say this, the version of history that we’ve been going on is just another narrative. So, I’ve taken the narrative that I was taught and found the malleable points to insert an entirely different narrative that’s totally harmonious and runs in sync with the current narrative, but it’s a different way of looking at the world, a different perspective. I don’t try to change history so much and I don’t think there’s much benefit in changing the narrative because what happened already happened but there were a lot more characters in this show so you just widen the perspective. You don’t change things, but you add some spiritual, fictional accounts.

Humans, we’re very strange creatures. I don’t even think we’re from this planet, to be honest, because we are the only creatures that behave incongruously to the nature of this planet. We’re the only people who truly destroy without giving anything back. Even cockroaches, they still eat litter, but we just destroy things and fuck it up. Totally change some shit to where it can’t even be changed back.

The narrative that we have is based on the history that is already written by the victors. So, the victors of this time would be European or descendants of Europeans. That’s just a moment in time. It wasn’t always thus. Everybody’s had their shot at being the head honcho, and this is just one of those iterations that we just happen to be living through. That’s the way I like to think about it. It takes the bite off of things. Because history is so fluid, and if you think about the entirety of history, power always changes hands. Some group always seizes power. Some groups stay a little bit longer. Some people make really nice recommendations and then they go the way of the dodo.

from Umar Rashid, Battle of Malibu (In Three Parts) 179; Courtesy Plum & Poe

So, the narrative that I did, was more to inform the world that it wasn’t just white people or Europeans conquering the world just willy-nilly and everybody else is just sitting there clutching their pearls or milling some fucking wheat. Especially in the colonial period, the period in which I’m working, which roughly starts in 1658 with the death of Oliver Cromwell, and ends in 1880 with the Portuguese abolition of slavery, and the Berlin Conference and all that stuff. I’m basically talking about building a world where everybody exists. I’m not omitting anything. Yes, there’s slavery. There’s raiding, war, pillaging, raping, and all this stuff left pretty much intact. But I just augmented the narrative by combining France and England together, to Frengland. So, it’s this major superpower. So, because it doesn’t matter, France or England, whatever, it’s just human beings. It shifts things, but you still get a Napoleonic character and you still get a Toussaint Louverture. We actually follow a certain script. Self destruction and worldwide destruction are the name of the game. And we see it played out in the news narrative now, what’s happening in Ethiopia, Ukraine, or anywhere in the world.

I try to give an expanded view and combine the modern world with that—the narrative moves with the way the world is going. So, not only am I writing this story about the past, but I’m also talking about the now. And then around 2015, I started adding more future narratives—talking about space, cosmos, and spirituality. Sometimes it’s a little bit prescient because I’m so in tune with these three worlds, past, present, future. I’m not saying I got fucking special powers or anything, but when you do connect yourself to these realms, you gain an ability to predict what’s going to happen, because there’s not very many options. I mean, you can be surprised sometimes, but I’m rarely surprised by anything. So, now, after about 20 years of developing this body of work it’s almost like a fully fleshed out being because of all the stories that exist within it.

History often repeats itself so it can be depressing to think about the future if you reflect on the past. Is there optimism in examining an expanded historical narrative while pushing forward?

Optimism or pessimism are just two different sides of whatever they are balanced upon so I’m always that third stream guy. It’s just my nature to always be in the middle of things. Whenever you choose a position, there’s always going to be an opposite position. No matter what you do, it always dichotomizes. It always breaks down, boom, boom, boom, boom. I vacillate between optimism and pessimism, but I usually find myself in that bottom swing of the cradle, in that middle part, because that’s where you learn. You don’t learn on either of the extremes, but you have to go through the extremes so you can understand. You just can’t stay there.

You have such an encyclopedic mind bursting with historical details. Is history personal for you and what do you gain from it?

It definitely started off personally because I was trying to find myself. That’s this particular conundrum that Black Americans have. Because when we arrived in the United States, we were stripped of knowledge of our ancestral lands, of our religions and culture. And when we got here, we had to create a culture from scratch. So, it’s not to say that Black Americans are bereft of culture, it’s just a hodgepodge of a lot of different things that we had to create in order to exist here on our own terms. So, that’s where it started but then I wanted to know more about my ancient lineage. Like, you are the son of blah, blah, blah, the great king of, but that never worked out. So, that’s how it started off, this search for who I was.

And then, because it’s a global narrative, I was researching the cultures of other people. It started off with trying to find different Native American polities and how they responded to being completely decimated. And then moving over to the Caribbean and thinking about the Taíno culture, or the Carib culture, the Arawak culture. And then going into South America and the Quechua culture. All over the world you’ll find these people who’ve been historically marginalized. And so, you see how people cope. The Hmong people in Vietnam make these wonderful story cloths. They’re not Vietnamese, they’re not Chinese but they have their own cultural identity because it was a tapestry of all the experiences. So, once you expand, it’s not about you. You have to have a degree of selflessness and allow yourself to be obliterated and remade in the image of all of the things that you can possibly conceive. And so, that’s what I did. I had to obliterate myself to really absorb everything else. And so, now I have this cosmic perspective. I think the best thing is to obliterate yourself—to let that ego go, suffer ego death.

So, post obliteration, in your new formation, what energizes you to do the work you do, and where does it get hard for you?

Just dedication to the craft, to the work, to the narrative itself. I started this story, and I don’t believe in starting something and not finishing it. Every good story deserves an ending or for you to take it as far as you can. It’s important to me to tell these stories. There are so many characters and a lot of these stories are based on friends. So, I’m invested not only in the story, but I’m invested in the characters. I know how the story begins, I know the middle, and I know how it ends. As far as I want to take it within this corporeal lifetime, I probably still won’t finish it. It’s so much. It’s such a rich history. I’ve been stuck in the 1790s for 15 years. So, I got 300 years of history to finish. Somebody else is going to have to take up the mantle at some point. So, I will appoint a squire to come and assist me and learn.

There’s also selling the work, which is necessary for me to continue to keep making it. I have to sell it. So, sometimes instead of going for a straight narrative thing, I have to make some stylistic choices and I have to really use my brain to condense everything into smaller moments. And it can’t be this wide sprawling thing, which in and of itself is a good thing, because that facilitates me moving to the next chapter a lot easier. So the more exhibitions I do, regardless if they make money or not, the better off I am in moving the story forward.

from Umar Rashid, Battle of Malibu (In Three Parts) 179; Courtesy Plum & Poe

Is the story in the art the most important thing, and the selling of the work secondary for you?

Yes, the art is the most fulfilling because it’s the only thing that matters. Because without that, the other could not exist. And how fickle the art industry is. I sat and languished for the better part of two decades, and then after the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor murders, and with the water rights in the Lakota country there was a wide echo about decolonization. They were like, “Oh, hey, this guy. Looks like he’s been doing this a while.” I was like, “Yeah. No one was interested in decolonization.” I’m not saying I kicked off the whole movement, but when people started to learn about it, they just gravitated towards my work because it spoke to everything that people were talking about. But I’ve been doing it for a very long time, so I’m happy that I got discovered.

For those late comers there was already a rich narrative unfolding. So now, having decimated your ego and pulled it back together, and being a parent and all the things you’ve gone through in life, do you see power in longevity?

Being responsible for someone else’s well being—I mean, even if you don’t have children or a partner, you still have relatives or friends. You have to have somebody to serve. I think it’s necessary to serve. The most important thing to do is to serve something greater than yourself. Not greater in a sense like, “Oh, exalted one,” but just serve something else. And then the longevity, how that works out is that you just have more ways to tell different stories. You learn. You keep your ears and your eyes open. Having my kids and my partner with me has been magic. Regardless of financial or critical success, I wanted to give them something that they could be proud of to say, “My dad did this.” So, I did it. This 20 year journey, I achieved everything that I set out to do.

So, now, I’m just following the narrative until a new path presents itself. I’m just letting life teach me now but not pandering. I’m trying to listen to what’s being said. Because now you have these conversations about gender. You have these meta conversations about race. You have this cacophony of things that people are talking about because of the widespread availability of information, owing to the internet. The spread of ideas is very fast. But I caution people to stay in that space too long because it actually makes things less important. When you have too many things going on in your head, you’re just moving on to the next thing. It’s like, “All right, we conquered this. We solved it with a media campaign and moved on.”

I think in a lot of ways I see that becoming an instrument of widespread fascism at some point, or acceptable fascism. “We had a media campaign, we talked about it. We canceled some people, and now everything’s okay.” But it’s not, because you were talking to people who already agree with you.

There’s always going to be a balance. Duality is the nature of humanity. And that’s what brought me to what I’m focusing on now, which is harmony, taking two different things and equalizing. Back to that whole analogy of the swing. You get to that point but you can’t stay there, but that’s the glue that holds everything together. So, you have to remember, we’re not going to be able to change everybody. And I know, I don’t expect to…Because if I did want to change everybody, that would be acceptable fascism in this current place and time. So, stop trying to change everybody. Live your life, but always practice harmonics.

When you’re deep at work in the studio, what do you feel?

Well, anxiety because usually I’ve started the project so late. I wait until the last minute. I work from a philosophy of, store up potential energy and make it kinetic. But store up a lot of potential energy, like a massive wave. So, every show that I do is almost like a tsunami. It’s got that much force. There’s the research, the thinking of ideas, the crafting, telling the story, the flushing out of the characters. And so, you make this wall and you hold it up. But then a lot of times what happens is that I’ve built up so much that when I break the dam it’s like drowning in the ocean. I’m pretty sure in one of my past lives I probably did. But it’s that vision, drowning in the ocean—very tumultuous, waves crashing, it’s a chaotic landscape. And once you’re below the waves, it just settles. And you’re there and the waves are there. Now, at this point, you could actually die, or you could live, it doesn’t matter. Then once I get into that groove and I know that I can swim back up, again.

All that stuff that builds up, will always build up, so that energy has to be released often. So, I guess when I do a show, I feel very excited to do the show most of the time, because I get a chance to tell another part of this story I’ve been working on for half of my life. So, when I get there I’ve got to surrender to the wave, let it overtake me, and then continue on and let it be done. And that’s a great feeling.

But there’s also a postpartum depression when you create a project and it just overwhelms. It can overcome you. That happens a lot so I try to stay as busy as humanly possible, so I never have to feel that feeling. But ultimately, I feel it sometimes. Then there’s that sadness because as you’re giving away your ideas and things that are precious to you, you’re giving away a preciousness that you will not be able to recreate 100% because of the malleability of existence and all these things. And so, it becomes something else.

Umar Rashid, Storm King; Courtesy Blum & Poe

Were these things that you had to learn on your own, or did you have mentors to help guide you? And how do you share your experience in order to encourage others?

I do like to share, unsolicited, my opinion on a great many things. But I just tell people, I’m not trying to sway you to think any different way. I see where people are making mistakes, and if I can help you correct those mistakes, because that’s what humans do. That’s the reason why we have children. So we can create a better world. We’re leaving better versions of ourselves here. Well, that should be the goal. Unfortunately, it’s not always the case. But that’s how societies evolve. You produce the better version of yourself to leave behind for the rest of the people. And then they have to figure out their stuff.

But there’s artists, like Henry Taylor, who would come to every one of my shows when I started out. And nobody would be there but Henry would come and he was like, “Hey, you should do this different.” My friend Ricardo and my brother-in-law taught me all these things about how to paint. And Augustine Kofie taught me some techniques. And I just learned from the community, especially in a time when you and I were ripping and running before children and partners and everything. When we were running around, Los Angeles was a gold mine. There were so many people, so much influence. And it wasn’t so centered on movies or Hollywood. It was a whole organic scene. I don’t know, maybe it still exists. I haven’t really seen it, because I don’t go out. But I remember I was just astounded by how much was going on and how much was made. So, in that way, Los Angeles, the city itself, the geography, the people, the culture, this hybridized Anglo, Latino, African, Asian thing, raised me too. So, you can be mentored by the physical space in and of itself, and then break it down to individuals. But yeah, what I do try to tell people ultimately, my best advice is just be you and try not to be like everybody else.

What’s your ideal creative space?

The ideal creative space will be a lush temple dedicated to Artemis with multiple waterfalls and cakes of all different kinds, ambrosia, and fountains of champagne and other delicious intoxicating drinks. No, I mean, a harmonious, clean space that’s wide enough so I can flesh things out with decent lighting. Actually, I’m like a cat. I like small spaces. I like crannies, crooks. I don’t like to be totally exposed because there’s a time for that. That’s my more performative nature. But when I’m creating, that’s very internal. I like it to remain hidden, the Al-Ghaib. I like it to be hidden and then reveal. It’s like a magician’s trick. It’s transforming thoughts to image. It’s a form of alchemy. It’s magic, so the place has to suit that.

Now I’m not saying that if anybody were to offer me a giant warehouse studio that looked like a Google office with a personal trainer and a massage…I mean is that a possible future? My A.P.F., all possible futures.

So, harmony is the future?

Yeah. The harmony. When I become just a note, and it was like, Umar has transcended into a note.

Umar Rashid Recommends:

Frank Herbert’s Dune series (including the ones written by his son Brian Herbert.

The sea, or any large body of clean, cool water.

Walking in nature.

Embracing harmony in all facets.

Dreamtime.

- Name

- Umar Rashid

- Vocation

- storyteller and artist

Some Things

Pagination