On working intuitively

Prelude

Maia Ruth Lee lives and works in New York. Lee has had solo exhibitions at Jack Hanley Gallery and Eli Ping Frances Perkins Gallery in New York, and has participated in numerous group exhibitions including CANADA gallery, NY, Salon 94, NY, Roberts & Tilton, LA, Parisian Laundry and L’INNCONNUE in Montreal. She was the recipient of the Rema Hort Mann Grant in 2017. Maia Ruth Lee is currently the director of the non-profit after school art program Wide Rainbow.

Conversation

On working intuitively

Artist and educator Maia Ruth Lee on tapping into your community, the pros and cons of a formal art education, and learning how to navigate the complicated waters of the institutional art world.

As told to Annie Bielski, 2663 words.

Tags: Art, Education, Time management, Multi-tasking, Collaboration, Day jobs.

What do artists need?

Without a community, it’s hard for any artist to thrive. For me it was a slow process but I feel like I’ve put in a lot of time and effort to create that community for myself, without really thinking about it. And then, at one point I was able to step back and realize, “Wow, this is a community.” Especially in New York, where it’s bustling—everyone’s busy. Everyone is doing something. Everyone’s working on a project. It’s very easy to get lost in just being busy. But what I’ve learned in New York is that there are people who are busy as fuck who will still give you the time of day. And I think that is really what community is about, giving each other that time, because time is precious. Everyone knows that. Feeling like you’re being heard, you’re being understood, you’re being seen for who you are, and also doing that in return for other people is a constant sort of giving back—giving and receiving.

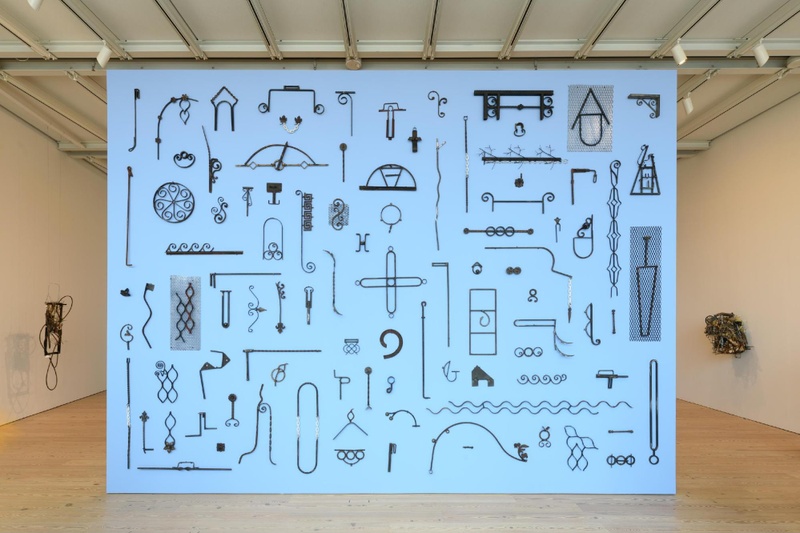

One component of your installation at the 2019 Whitney Biennial included welded steel objects that formerly existed as parts of fences and windows. You assigned meaning to the forms you created in an accompanying guide, which read “Follow the Pathway Within.” Can you speak about this work and the creative path that led you to it?

I call the individual pieces glyphs. I started working on them not so long after I arrived in New York City, actually, kind of by happenstance. I was making a sculpture at a hole-in-the-wall welding spot near my studio and I just happened to find this pile of discarded steel pieces that were leftovers from fences and windows, like you said, and I was instantly drawn to them because they reminded me of home, which is Nepal. These structures exist in most cities and this includes developing countries. Kind of on the spot I just asked the welders to give the metal scraps to me, because they were going to discard them anyway. I held onto them for a while and as an exercise I started assembling them together in different arrangements. It was really satisfying to me that this idea of symbolism, this idea of a signifier, this idea of new language or a lexicon sprang to mind and I was really interested in creating this new body of work.

LABYRINTH, steel glyphs, 2019. Photograph by Filip Wolak.

Every single piece is completely unique, and it also holds a little bit of history of where that piece is from. Some of the pieces are old, like old fences that are brought into the studio to get fixed or get repaired or get chopped up and discarded as well. They take the pieces of steel that are reusable, and the pieces that I’m left with are really just like leftovers. I really like working with salvaged metal. The idea is that the pieces guard and protect households and spaces, but it’s also about barriers as well. Conceptually I was really into the idea of working with a physical structure that protects but also divides people. I went to school for painting in Korea, and painting in Korea is very old school in the sense that it’s all about painting realistically and being technically really good.

Coming away from that formal education is really fun for me. The metal shop would only really give me 10-15 minutes of their time, because they’re making real structures. So, on the spot, I would take these discarded pieces and lay them out on a large table. There’s no sketching involved. There’s no preemptive thinking involved. Everything is just on the spot, so it’s very organic. It’s very quick. It’s very intuitive, which I really, really, love. All of the steel glyph pieces are made within probably about 10 seconds, between 10 seconds and a minute. The welder goes around and just zaps, and that’s it.

It really kind of eliminates the whole process of over-thinking. For me—and maybe I can speak for some other artists, too—my formal education kind of gets in the way, and sometimes I wish I didn’t have it. Sometimes I’m glad I did, but sometimes I wish I didn’t because I do tend to overthink. With these pieces I feel very free. I can be myself without really over-judging the situation or the material. Once I bring them back to the studio, that’s kind of when the work begins. I arrange them and I look at them and assign a name to them. And it’s really fun because symbols and signs in general are very intuitive anyway, and I feel like these shapes and forms are innately in all of us.

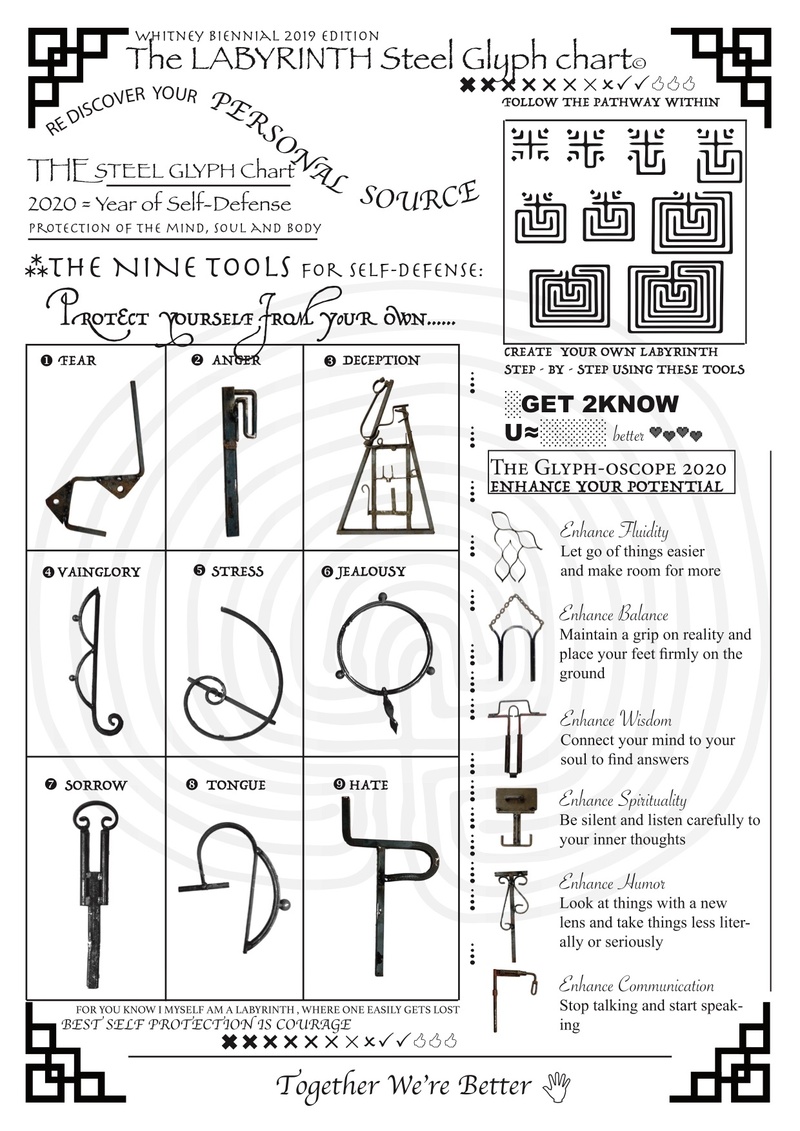

The one piece of feedback I got from people is that they all look somewhat familiar to everyone. I like that. I like that idea that maybe you’ve never actually seen it before or you can’t really remember where you’ve seen it before, but these are all kind of a very subconscious language that I think that human beings already carry. So, tapping into that through my own intuitive process was really fun, and then assigning meaning to it was the more quirky, funny part of the process. There’s protection against your own fear, anger, deception, vainglory (meaning vanity), stress, jealousy, sorrow, tongue (meaning talking too much), and hate. So, it’s really like preventing yourself from being fearful, being angry, being resentful, being vain, and being stressed out.

I feel like stress is a big one for me. I’m always like, “How can it be less stressful?” I like this idea of these symbols as indications, as a reminder. “Follow the Pathway Within” is verbatim something out of a pamphlet for a spiritual guide, almost like a cult guide. Having been brought up in a super Christian family—my parents are missionaries and so Christianity was this very heavy thing for me in my childhood—I’m trying to approach [that language] with a touch of humor. At the same time the pseudo-spirituality is not not spirituality either. Everyone is really into astrology now. I think it’s actually really interesting, and at the same time really funny, too, because people take it seriously as much as they want to. At the same time you’re like, “What is this information? Where is this coming from?”

We’re looking for a sign.

Looking for a sign, yeah. I think that desire is innately in all of us and that’s why I think it works. Everyone is waiting to hear some good news, and I think that sense of hopefulness is something that’s universal. I wanted to tap into more of a positive side of what’s happening in this world, especially for the Biennial, having to talk about myself and also my work according to the times that we’re in. It’s very heavy, heavy, heavy and a really big task. So, I really try to see it from different angles. I wanted to tap into that hopefulness, so the piece is called “Labyrinth.” The labyrinth is one of the most sacred, strongest, most ancient symbols we know of. As I was researching labyrinths, I found it really interesting that labyrinths and mazes are perceived as the same thing, but they’re actually quite different. A maze has several pathways, so it’s more like a puzzle. It’s about navigation. It’s about figuring it out. There’s a right way and a wrong way. Whereas with a labyrinth, it’s not about a puzzle. It’s not about figuring out navigation. There’s only one pathway, so you follow one path. It leads you to the center, and then it leads you right back out. So the purpose of it is not to go anywhere; the purpose itself is a pathway. The idea is that meditation is what’s really lacking for myself. Not only for myself, but also for the times we’re in.

Throughout your art and your position as Director of Wide Rainbow, there is an overlap in themes of accessibility, empowerment, and tools. How does your role at Wide Rainbow inform your studio life, or vice versa?

Wide Rainbow is a 501c3 non-profit after-school art program. We work to create more access to art for under-served neighborhoods in New York. Wide Rainbow is primarily led by working artists in New York. They volunteer their time to either lead a walk-through of their exhibition at a gallery or museum, or they volunteer their time hosting a workshop on-site with one of our partnering communities.

Wide Rainbow is made up of a group of many women. I’m the Director, then there’s Ashley Gail Harris, the Founder and Executive Director; Morgan Connellee, Director of Development; Lola Kramer, Curatorial Director; Eliza Ryan, Curatorial Director in music and in art; there’s Diamond Stingily—we call her Artist-at-Large. She is also part of the Advisory Board. Ellie Hunter is the new member, she’s an artist, the Arts Coordinator, and she’s also a part of the Advisory Board.

All of these people combined are what makes the group. We, as a group, try and figure out how to move forward, how to make this work better. It really changed my life. I still can’t believe this is my job because it’s really perfect for exactly what I’ve always wanted to do. I’ve always wanted to be some type of educator but didn’t really know which angle. At one point I was thinking, “Do I want to be an Art Therapist?” I’ve always wanted to work with children and had done some of this type of work back in Nepal, when I was living there.

The way it informs my work is that I feel like priority-wise, Wide Rainbow comes first. I mean, obviously, my son Nima comes first, but when it comes to work, I would say Wide Rainbow is like 70% and the rest of my work is like 30%. Maybe even more actually—maybe even 80% and 20%. I don’t know how it really affects my work except that I have less time to do it, but it feeds me in so many different ways. It really inspires me to be constantly working with such a large community of creative people. We have 2-3 workshops a week, we’re doing multiple walk-throughs. We’re doing on-site workshops. We’re doing a lot of different things, but every single experience is so inspiring, not just for the kids, but to me, too. I walk away being very energized. I’ve never felt exhausted. Maybe physically, sure, but emotionally I’ve always been inspired. I feel pretty lucky to be doing that.

What advice would you give to artists working within a flawed system or institution?

What do you mean by flawed institution—the actual art world?

Yes, and I’ve been thinking of the letter you wrote addressing your decision to remain in the Whitney Biennial, after other participants requested withdrawal of their work in protest of board member Warren B. Kanders and his affiliations. What would you offer to artists navigating difficult decisions?

I think that goes back to the idea of community. The one really interesting thing I thought was, the whole controversy sort of made everyone think about the fact that everybody is involved. It wasn’t just the Whitney. It wasn’t just the artists. It wasn’t just Kanders. It actually involved all other board members of all other institutions, all museums, all galleries, all curators, all art-lovers, museum-goers, artists. This conversation, this dialogue kind of included everybody, which I thought was a really interesting thing because we’ve never really had that dialogue before… that this discourse had never really arisen in this big way, where everyone is sort of like, “Oh, who have I sold to?” And galleries are like, “Oh, who are our clients?” And museums are like, “Who’s on our board?” It probably made everybody stop to think for a second, which I don’t think is usual. Everyone is so easy to just jump on whatever wagon to sell, to make money. I think that in a weird way it made everyone sort of reflect but also realize that whatever angle you take is going to be hypocritical. That, I guess, is pretty unfortunate.

Steel glyph chart for LABYRINTH, 2019.

Artists having more of a sense of things, I think, is what I would say is the most effective way to navigate. Whichever way it is, having a stronger voice but not being afraid to be crushed by it. For example, I was like, “Oh, I’m gonna get so trolled and people are gonna hate me for this.” But then I was like, “You know what, I would sleep better at night if I just said it.” I felt extremely relieved to just say what I had on my mind instead of just feeling worried about what the pros and cons are.

Without the artist there is no art, and it’s funny because if there’s a hierarchy, we also fall to the very last. So, we’re in this weird, fucked up situation where we’re making the actual work, but we’re also the least considered in some ways. But if we’re able to create a community where the community is what is stronger than the institution… I think this case was a very strong example of that. The fact that [Kanders resigned from the Board of the Whitney as a result of protests] is because of the community, and the sort of urgency around the issue tracked by the people, right? Especially the artists.

Without the money, without the backers, without the funders, how does [the art world] operate? How will it ever operate? I also felt like it was important for me to stand up for the staff, too, because they’re really stuck in this shitty, shitty position where their jobs are on the line so they really can’t say much, but I know that a lot of them were really struggling in this whole process. And if I had a shitty experience with the whole Biennial, I would have been like, “Yeah, whatever, yeah, fuck it, I’m out.” But I actually had such an incredible experience with them, and I have so much respect for the curators. They were so supportive throughout the entire thing, being like, “We support you withdrawing your work. No problem. We are there with you.” I knew that came with a lot of hurt, with a lot of pain, too. This really pushed everyone’s boundary and tested everyone’s stamina, in a way.

How has your relationship to time and your creative work shifted since becoming a mother?

Oh, wow. It’s weird. Now that I have my life structured around Nima’s life, it takes me out of the self-sabotaging thing where I mope around. I thought, “Oh, I’m not going to have the time to do anything.” But actually it eliminated all of this time I didn’t even know I was spending. So, counter-actively I became more productive. Least expected. I don’t think I’ve ever worked as much as I have since Nima was born. Say I have 9:00 am to 3:00 pm in the studio, now I will go and use that time, whereas before I’d be like, “Yeah, sure, today is studio day.” But then I can also take a break and go do something else. So, that part was refreshing to me. I mean, I still really, really yearn for doing nothing. That’s real rest, right? Doing nothing is real rest. Not even sleep can refresh that. Sometimes I really dream of just doing nothing.

Maia Ruth Lee Recommends:

Photo Kathmandu (biannual international photography festival in Nepal)

Seollong tang (a white bone broth Korean soup)

Gowanus

- Name

- Maia Ruth Lee

- Vocation

- Visual artist, Educator

Some Things

Pagination