On the creative process as a continuous flow

Prelude

Monica Narula is an artist with training in cinematography and filmmaking, and a background in English Literature. She formed Raqs Media Collective in 1992, along with Jeebesh Bagchi and Shuddhabrata Sengupta. The collective practices across several media, making installation, sculpture, video, performance, text, lexica and curation. The members live and work in Delhi, India. In 2000, they co-founded the Sarai Programme at Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi and ran it for a decade; they also edited the Sarai Reader series. They have shown extensively throughout the world, as well as curated numerous exhibitions. They were the artistic directors of the Yokohama Triennale 2020, Afterglow, where they developed sources around toxicity, care, and the luminosity of friendship.

Conversation

On the creative process as a continuous flow

Artist Monica Narula discusses the value of collectives, having multiple starting points, how an idea demands its own form, and why the process of making is always in-between things.

As told to Brandon Stosuy, 4556 words.

Tags: Art, Design, Writing, Collaboration, Inspiration.

How do you decide what form an idea will take?

I really don’t have an answer for that, in the sense that I believe that an idea demands its own form. I really don’t have a better answer than that. And, some things just feel like they need time. A lot of our work is time-based. We studied film, so there is a cinematic practice at the heart of much that we do. And there’s also, at the heart of it, a relationship with time, or at least an awareness of a relationship with time, which has been a big part of how and what we look at: time both as material, but also an awareness of time. For this reason, some things call for a cinematic and time-based response. And other things take other forms: a sculpture, a singular image, a text, and so on. But it is interesting to the self as to why something becomes a sculpture and something else doesn’t.

When I was much younger, and a bit of a smart-ass, I remember reading a potter speaking about how the “pot makes itself,” and feeling very kind of like, “Oh come on that doesn’t make any sense. I mean, the material cannot determine the form…” But it’s true. The pot does make itself. I mean, you are the maker, but you’re also not.

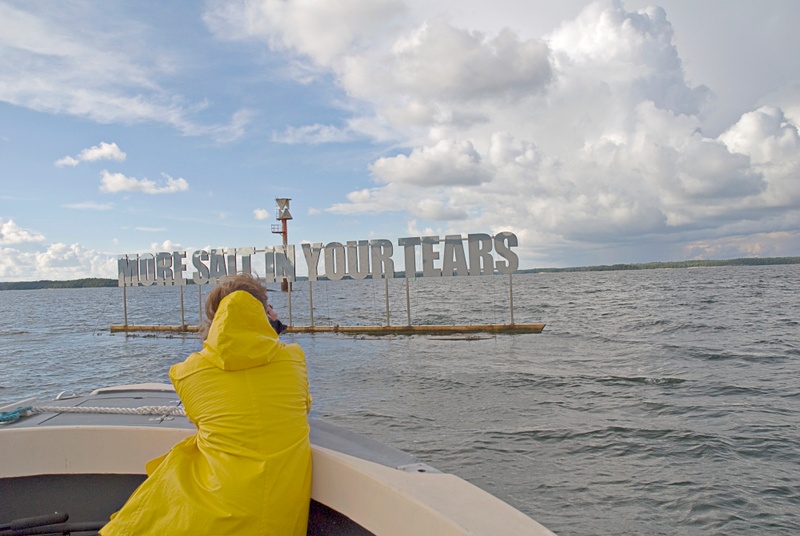

More Salt In Your Tears, 2011. Courtesy Raqs Media Collective and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Is there a difference when you make something as a collective versus when you make something as an individual?

I don’t think that there’s any distinction. I won’t talk about everyone, just about myself, but we don’t actually make any practice—creative or artistic in the broader sense—alone. I can’t even imagine making a work of art of my own, or a work in any way. Even if it looks like it needs one person’s—or my hand—to form itself, there will still be a conversation that will help it to reach that form. Or, it will be made and then discussed, and then remade or trashed, or whatever it might be.

Not because I think that the collective is an arbiter. But I think it’s because—for me—the process of making is always in-between-things. We live in a time that is between the past and the future, so the present is a time only in-between. It exists because we have at least an understanding of the fact that something went before and something will come after. I mean, there’s interesting discussions on how long the present actually lasts, but also, when we talk about the present, what we find ourselves being attentive to is that it exists in- between. Actually, a lot of things exist in-between—in-between people, in-between moments. So, it’s not the thing in itself; it’s what is around it.

As you know Raqs also curate exhibitions, and I remember having a public conversation around the time we were curating the Shanghai Biennial, when I said that not only are we interested in the specific works of art—that, obviously—in the exhibition, but also in the moments that happen in-between works of art. When you stand at a certain place or at a certain juncture and junction, and you turn your head, what you see when you look in one direction and what you see when you look in another are all the things that make an exhibition, as much as the works of art that might be in the space. I will say the same thing holds for our creative practice, too. We are the people, but it’s the flows in between that make the work of art.

I will say it holds for everyone and for everything: the social is also what flows between us, as much as what it is that we wish to take cognizance of as that. It is the spaces in-between that we—perhaps—need to be more attentive to.

The Blood of Stars, 2017. Courtesy Raqs Media Collective and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Do you see your earlier works shifting based on what you’re making now? Do you see everything the collective is creating as connected or do you see them as discrete objects?

We’re quite cavalier. We will quite often take something from our own past, especially if it’s film or photograph, and re-play with it—in a performance or in a conversational gambit, or in a more theatrical notion of what a conversation can be. These things become new kinds of facets to what is being thought about and then it becomes possible also to not think of time durations as singular and linear, but in multiple directions.

It is also interesting sometimes to look back at something and to see it both as an entity and as part of a flow. Because it is also kind of a way of looking, not at yourself, but at how one looks at a historical formulation. How does it stand both as itself, for that moment of time, as well as reflecting what that moment in time was. It is also how it leeches in, and percolates, into the present. And yet how it stays elastic, over time.

When you’re curating an exhibition or your own work, do you find it hard to find a point to stop, to say, “Okay this is what we’re putting in this particular frame”? Because there is this flow backwards and forwards, and to the sides. How do you decide when something is finished and when something is able to be shown as a completed work?

Many years ago, we began a project that we did over four years. This was when we were really quite young. It involved talking to master cinematographers in India—we travelled all over the country and spent a lot of time talking to cinematographers who had shot films from the ’50s onwards, whomever we could find alive, all the way to the then-present.

It was a fantastic experience in the talking of the image and of light, and what constitutes an image. It was a conversation I still feel is relevant because when you make a frame with a camera, you choose to frame something. This holds for everything—nothing exists in and of itself, it is a matter of the “frame” you give to look at it. But to get back to speaking of the making of the image: You know the shot you want, your mind knows but it is also partly intuitive; in some ways, your body knows more than your mind.

I remember this one moment when we were talking about the question of lighting a shot: Raqs had asked, “How do you know when to stop lighting?” One cinematographer told us that he kept an assistant who was quite expensive as assistants go, and one producer got really upset with him and said, “What is this? Why are you hiring this young man who doesn’t do anything, he just sits around and then talks to you for five minutes?” And he said, “Because he tells me when he sees where I have reached with what I’m doing, and that’s the only reason he’s there.”

I think it’s great to be in a collective because of some of those conversations, because sometimes you need someone else to tell you that perhaps you’re going too far or that you haven’t gone far enough. And sometimes your body just knows, right? You just know it because you have been practicing. The word “practice” is such a wonderful word because it has time built into it: You only can practice if you practice.

The Great Bare Mat 2012. Courtesy Raqs Media Collective and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Conversation on Nostalgia, 2012. Courtesy Raqs Media Collective and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Are you all ok with abandoning an idea or a project or do you try to wrestle with it until it finds a form?

I would say mostly we wrestle with an idea. For example—and we were just talking about this the other day—the year 2020, even though it felt like such a long time, had 28 of the world’s fastest days in terms of the movement of the Earth. It’s a matter of less than a second, but the point is that the Earth was moving faster than it could have been, than perhaps it should have been. And just as it was being shared between us, and we were saying, “Doesn’t this blow your mind? Isn’t that amazing?,” etc., and we were talking about it and saying we should do something, someone writes in saying, “I’m working on a really micro project with no budget, but you know, dah-dah-dah…” And then you’re like, “You know, this idea goes there.”

A couple of years ago, we were in the Proust Archive in the University of Champaign Urbana. So much of Proust deals with time, of course—Remembrance of Things Past and In Search of Lost Time—and it was quite a frisson to be there. And when I was shooting pictures in the Archive, mostly of the letters and fragments of text written by Proust, because these were in vitrines, it was almost like I was shooting the passing of light on the surface of the vitrines.

You know how something passing changes what you’re seeing?

So now we are making a short film on these images. I don’t know where the film is going, but these two things—the speed of the planet and the passing of light on Proust’s letters—will come together and find a way. Now, in this process, things will be tried out and lost, right? So, we might say, let’s try this, and you know, let’s start another edit. Or, let’s change the rhythm completely. A certain set of sparks happen; those sparks lead to other sparks. It’s not like there’s a formed idea; it’s almost like, “this has to start now.” The image pushes the idea, and then the idea pushes the image. It’s never a moment in which you are ever so confident until it’s finally there.

That’s more our process. And perhaps it’s a process that happens in that way because a lot of it has to be put outside of yourself, it has to be in-between. Whether imagistically, or verbally, or in any other way.

There’s quite a lot of rigor in your work. I could imagine each project showing up as a book project or a conversation or a lecture, something curatorial. Because of this complexity, and this ongoing-ness, I can imagine there also being a sort of momentum, where you just keep finding new wrinkles or new pathways. I was curious if as a collective that helps provide momentum with the projects. That, because it’s this ongoing practice, it just keeps going and going…It feels self-generative.

I like this idea of momentum being generative. The flow in between these two ideas is really great. I think you’re right. There are moments when sometimes you feel tired, or low in charge, but then there’s two other people who might not be. Someone else is full of energy while you’re kind of flopping around. That helps. You’re absolutely right. When the conversation is driven by ideas, and it is driven by this kind of flow between facticity and ficticity, and since we all live in this complex world, there’s the matter of being aware of that, but also of being aware of how one has to read against given grain.

We are more aware, increasingly, of how dispositional practice is, and needs to be. It has to be dispositional because that is the momentum.

Not what you’re making, not so much. Non-making practice is an interesting kind of condition. Because sometimes it’s just coming to the space of the studio and staring at a book cover and not being able to do anything else but being aware that looking at this book cover is as generative as having a conversation. And after that, sometimes, something will emerge. It is about being aware that it is not just what the world is doing—that I’m not reacting only to that. I have to have knowledge of what’s going on, but at the same time, the reason I’m paying attention to it is not because it’s a bad world, not from that externality, but because it emerges from within what one must be in the world, from that internality. What is it to be in the world? That question. That’s a dispositional question. That creates its own kind of flow.

Utsushimi, 2017. Courtesy Raqs Media Collective and Frith Street Gallery, London.

How has the pandemic affected this flow and this collaboration? Can you still go to a physical studio?

From March of 2020 till December of 2020, we did not come to the studio—which was seven, eight months. Unheard of in our lives. We literally meet every day. If all of us are in the same city, then we will certainly meet every day. And if we’re traveling together, we are together all the time. Since December we have been coming to the studio, and we hope that now maybe it will not get as bad as it was some months ago, although the numbers are not looking good.

Anyhow, one interesting thing that did happen in this time of companionable distance: in the very many Zoom conversations that we were part of—there were many invitations for talks and meetings, which I think was coming from a huge thirst for conversation in the pandemic—we kept asking, “How does one think this moment?” There was a lot of churning with that. I guess because we know each other for so long, and because we’ve been working together for so long, we sort of think we know what the other person is going to say. And oftentimes we are right. Of course, sometimes we are wrong, but mostly one kind of knows the tenor. But because we were not seeing each other, because the dynamic of the present physical body wasn’t there, I found that we paid much more attention to each other when the other person was speaking in public. That was a bit of a surprise, but a good one. Sometimes the everyday needs to be interrupted for you to be just more attentive to its capacities.

During this time, it’s harder to come upon an idea by surprise, or to simply wander into something. There’s this confinement or separateness. Has that shifted the way you’re thinking about ideas? I think of it as an open stack library, where you can wander, versus a closed stack library, where you hand the librarian a card with a title on it and they get it for you. You were saying before, when you were looking at the Proust library, you noticed the play of light on the vitrine and that became the genesis for a project. How has quarantine shifted the discovery phase of your work? Are you finding new sources?

“Source” is a word that we’ve begun to use fairly often. When we curated the exhibition “In the Open or in Stealth” at the MACBA in Barcelona in 2018, we started to talk about sources in a concretized way. We said, there is a distinction between resource and source; the latter’s function is of transmuting. You use a resource to make something else. But a source, as with a river, is a point of departure. It is a beginning, a starting point, and you do not know, necessarily, where it is going to take you.

For the Yokohama Triennale, which went up in July 2020, and for which we did a first publication in November 2019, we offered the idea of “Sources” as key for the process of our Triennale’s becoming, and we presented at the outset our sources that we were drawing from and drawing to the exhibition. In that instance, for “Afterglow,” we were bringing in ideas around toxicity and care, and luminosity and friendship. It was a set of complex ideas, and we were proposing each of them— through texts—as a “source.” One text was a dialogue that happened in the ’90s, between an anthropologist and a dockworker, Nishikawa Kimitsu, who was also a philosopher. Then there was the literary scholar Svetlana Boym’s evocation of the luminosity of friendship. There was Nobel Prize winner Shimomura Osamu, on the luminosity of jellyfish. There were five such text-sources.

When you acknowledge to yourself that there are multiple sources to your process, what this does is, it expands the genealogies of the sources. You can have, I wouldn’t say global, but multidirectional genealogies. It doesn’t always have to come from the direct path that you think you know, and where you can draw a clean arc. And you can pull, and you don’t have to be so afraid of taking a detour or an unconventional path, and because it’s only a source, you can say, it’s a source for me, I can push myself, I can engage with this idea. You can expand the world that you bring your sources from. And also: time. You can produce a non-hierarchical and non-rivalrous relationship between different moments, subjectivities, histories, and terrains—from today, from yesterday, from 500 years ago.

We have found the idea of the source to be a very productive one. Especially when you say to yourself, what is it that I wish to do? Partly that is, quite obviously, a question of what one wants to do in what one is doing. But also: what is it that my practice is doing in being in the world?

When one comes to this with an aware relationship with Sources, one makes a different world. One can then say: I am making a world that is not so flat, making a world that is more layered, making a world that is more woven across time. And I think that is one of the ways—I wouldn’t call it a methodology and I keep coming back to the word dispositional—by which one can remake the world without causing a crisis or paralysis either of the self or the other. This also allows a generative relationship between various strands.

That does seem to be a part of our practice, too: engaging with the world itself, outside of a museum, and acknowledging creativity to the everyday. To me it really is a question of an awareness of what one is part of. The creativity of the everyday is obviously the starting point. But if you were to ask me, “Are you creative?” I would probably say no. Because honing a disposition, a capacity, is the first principle.

One of the things I find very important is the idea of repetition. This is something that comes from practice as being in riyaz, which is what Hindustani classical musicians do everyday—though even generally it is used for the idea of practice in the everyday. This means you repeat, you repeat. And further, what is liberating is that it doesn’t necessarily demand an enactive energy all the time.

A simple example I can think of, let’s see, I don’t know, like knitting. I love knitting—though just very basic, very simple knitting is all I can do. Is that creative? I don’t know. But what I do know is that it provides me a certain kind of presence, which allows the mind to function in different ways. Perhaps here I can use another musical connection for the simultaneity: like being a piano player and doing two different things with two different hands. Permitting yourself to simultaneously doing multiple things, with awareness.

Many years ago, in a discussion, a colleague in Cybermohalla said, “If you want to talk about fearless speech, you must also speak of fearless listening.” And talking to you, what she said is coming back to me—you know, she was saying, if you want to think about anything, if you want to be enactive, first you have to be attentive. You can’t always think about being in the world if you’re not willing to let it come into you.

As a collective, so much of your practice involves listening. A lot, I imagine, is negotiation and figuring out which ideas bubble to the surface, which ones disappear. You were saying before how you often can’t remember whose ideas were whose, and things get fuzzy. Is that part of the practice, this removal of ego?

Do we have to call it a negotiation? [laughs] I’m wondering if that is the right word, because I don’t think it’s a negotiation. There is definitely disagreement; I guess we draw sometimes from the history of dissensus rather than consensus. But when the thing is formed, when whatever the form is going to be appears, unless everyone feels that it is right, it does not become public. Sometimes it goes into the world because everyone in the collective just knows and there’s this moment when everyone turns to each other and says, it’s perfect, it’s working. And then, sometimes, you have to just keep arguing and at some point the other person says, yes I get it, I get why you’re saying what you’re saying. It’s not a negotiation in the sense that—I guess—it’s a process. The process has to take its form, the process has to be given its own kind of flow. Work emerges from that. I would say that is the artistic process: This flow is the artistic process. The question of the ego is irrelevant, because no one can make a work of any kind if it is the ego making the work, and you know that, you’ve seen shit work made by really famous artists. If the ego enters into the work, whether you are singular or a collective, it’s going to lead to crap.

I like the idea of the process itself being this flow. It feels continuous, and keeps going. It’s there, and if you think of it as a river or something, you go in and pull ideas out here and there, and it continues. Even if you’re not actively doing that, it’s still just going.

Yes! There’s a publication coming out soon from Germany called Untranslatable Terms of Cultural Practices, which is stemming from the fact that different languages have words that cannot be translated, but also offering them as conceptual ways of thinking. They’ve asked a number of people to offer words that cannot be translated. So, we offered the word Anta(h)shira, which is a Bengali word which is often untranslatable; it is to be found only in medical dictionaries. But what we have or translated for ourselves, pulling from what is, is that there are flows that always exist, subterranean within, and they sometimes express into form.

I love how you’re reading practice as that. I mean, you’re reading practice as anta(h)shira. It’s exactly that. I should have thought of this. It is that. It is a latent flow that manifests itself in different forms. And it’s always there. And I think what we’re saying is that there are always flows that are—and we’re thinking about other things as well—which find expression, and especially moments, social moments. And you wonder where that comes from. Why is it that today, suddenly there’s palpable unrest? You know, why is it that people are on the streets? What is it that has changed from yesterday to today? What is it that causes this to shift? Sometimes a spark doesn’t seem to be adequate to what emerges; we are saying that this is the anta(h)shira, this is the flow that is there, and then at some point, it finds expression.

Monica Narula Recommends:

Five Verbs

-

Doing acts of repetition and pattern; and then dissolving the patterns to find new ones afresh. This allows stillness and re-fractalling of the mind’s fluctuations. In a trek along a mountain range, looking is the composing, and then the decomposing of impressions. The walk is the rhythm. With ink on paper, minutes move into hours. Marks become sentences, even as some remain unattended and remain as stain. When you see patterns you can understand stains. Time halted gives the sense of time moving.

-

Practicing fearless listening. We can speak of needing fearless speech, but what use is it if we don’t have fearless listening? Moving between enclosures is part of living. All enclosures are sonic environments made of words, scratches of sound, melodies, silences, and a persistent tone. Listening is a way to live, enliven, and sense the world. It is also a way to becoming aware of that which is being disturbed. Fearless-ness is an inner deliberation on the threshold of listening. Affection, aggression, anxiety, and abuse knock at this threshold - seeking antidotes, or an embrace.

-

Reading through a genre—realizing it is both milieu and transmission. Choose boldly: these days I am spending a lot of time with science-fiction. The world-making that is called into being speaks both to the future (obviously) but it is as much a reading of the present. It is only when I read through the genre that I guide myself to questions of limits, and of extensions of the horizon. E.g. Is time-projected a breach of inertial time that we all seem to take for reality, or is it masquerading as an escape without actually permitting escape? The most complex questions are explored in genre. Film noir as a genre tells us more about class and gender anxieties than any other “masterpieces” standing in solitary isolation.

-

Make conversation with commitment and skill. Think of it as needing both - like making love does. Conversation too is a site for making and merging. It is a practice, and it is a surprise. It requires more than one at a time, it cultivates listening, as well as a recognition of what we inhabit: a sense of the passing hour and the uncanny encounter of possible epiphanies.

-

To uncaste is to act against ingrained dispositions, to strike at in-egalitarian principles and congealments. To uncaste is to break down structural hegemonies that are partly visible, partly invisible. It is to not give in and give up. It is not about “one day all will be right-ed,” or that “one day it ought to be righted,” or “it is too grainy to deal with.” It is to accept that the most intimate is also the most entangled with coercion, and of the compulsions of many centuries.

A Day in the Life Of, 2009. Courtesy Raqs Media Collective and Frith Street Gallery, London.

- Name

- Monica Narula

- Vocation

- Artist

Some Things

Pagination