On using photography to create what you can't see

Prelude

Stacy Renee Morrison is a photographer who often forgets what century she is in. As fate would have it, she encountered a 19th century trunk abandoned on a New York City street and embarked on a nearly twenty-year project making photographs about the trunk’s owner, Sylvia DeWolf Ostrander. Most recently in 2020, Morrison exhibited the contents of Sylvia’s trunk along with her work interpreting Sylvia’s life at the Merchant’s House Museum in New York City. Morrison teaches in the MFA Visual Narrative Department and BFA Photography and Video Department at School of Visual Arts. She recently launchedSylvia, a silkscreen clothing line featuring images of Victorian women and ephemera.

Conversation

On using photography to create what you can't see

Visual artist Stacy Renee Morrison on photography as a metaphorical time machine, collaborating with the dead to make art, and shaping a creative practice around a fascination with history, ephemerality, and memory.

As told to Karrie Witkin, 3366 words.

Tags: Photography, Art, Process, Inspiration, Production.

Many of your projects begin with you finding a photograph of a woman from the past and feeling an overwhelming desire to know her. How did you first encounter this kind of inspiration?

When I was six or seven years old, I was totally obsessed with the Titanic. My parents had bought me this large picture book about the ship, and I found a photograph of this young girl named Loraine Allison in it. She was the only child in first-class to perish on the ship, and I would look at her photograph every night. I would sleep with the book underneath my bed. I don’t even know exactly why. Maybe I thought I could protect her.

In high school, I thought constantly about Anastasia Romanov. I read everything that I could find about her and I liked to wear white dresses like she did. I really wanted to believe that she survived the assassination of the imperial family, and at that time there was still the possibility because they had not found the remains of the family yet. I think these early strange obsessions were the first indications and the motivations behind my artistic practice. I think it all begins when I perceive that a dead woman needs my help.

Photography is your primary medium, but your practice also involves digging deep into public records and historic archives to better understand your subjects. Do you have any formal training as a researcher?

I love being around old photographs, letters, primary materials from the past. I could probably live in a library. When I was an undergraduate, my goal was to pursue a PhD program in women’s history. Then I had taken one photography class in college that really resonated. I would spend hours in the back and white darkroom, and I fell in love with the process.

I decided to go to graduate school at the Gallatin School, NYU, where I could combine all these interests together in a joint art and humanities program. I studied 19th century etiquette as the academic component to my degree and photography is the visual arts part. At the time, I wasn’t certain what I would actually do with this combination, but I have actually managed to stay true to these dual loves in my work, both personally and professionally.

Cherish © Stacy Renee Morrison

Can you describe how all of this comes together in your artistic practice?

I study the personal effects of women from the past with the attentiveness of a detective, caution of a conservator, engagement of a fiction writer, and the curiosity of an artist.

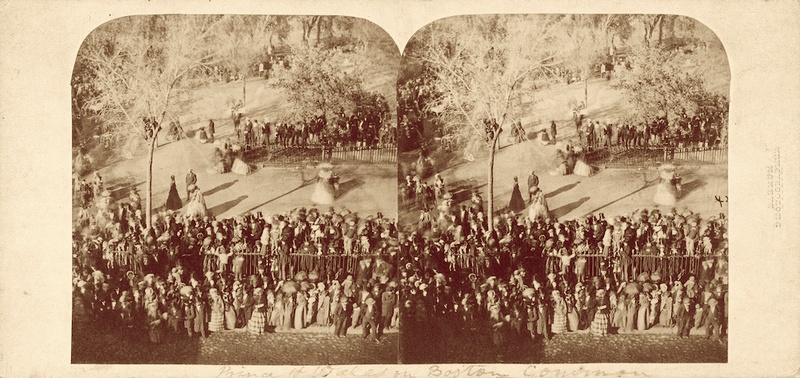

My photographic series, The Girl of My Dreams, ties all of these themes together. It began nearly twenty years ago, when my roommate found a small trunk filled with 19th century sentimental keepsakes: calling cards, photographs, paper dolls, an invitation to a ball honoring the Prince of Wales in Boston in 1860. The trunk had been discarded for garbage on a New York City street. I learned that it belonged to a woman named Sylvia DeWolf Ostrander, who lived from 1841 to 1925 and came from a prominent family in Rhode Island.

My background knowledge of the societal expectations for 19th century women made me recognize Sylvia’s trunk as a precious treasure. I also understood that the trunk presented the gift of a voice. I knew in a sense that I needed to become the vocal cords for this 19th century woman. I realized that I was Sylvia’s gateway to a life in the present, and I began trying to find everything that I could about her. Fixating on researching her life began rationally enough, but it soon became an obsession. I was falling in love with this dead woman.

Eventually I found Sylvia’s great-granddaughter, who generously allowed me access to her diaries, letters, clothing, and other ephemera. The more I learned about Sylvia’s life though, the more I then could draw from my own inventiveness to make work about her life. I used her journal entries and translated them into photographs. I took photographs of her Rhode Island homes to recreate those moments. I dressed in her clothing, which creepily fits me perfectly. She had to have been my exact height, because her dresses are the perfect length. I’ve had to ask myself, what did she see? What would have been of interest to her? If she had a camera, what photographs would she have made?

Becoming © Stacy Renee Morrison

Your images represent what Sylvia would have seen or experienced herself, and sometimes they seem to represent something more subjective, what she felt or perhaps what you believe she felt.

Yes, exactly. Reimagining history takes on various forms. I am a fact-finder and an architect of historical fiction in my work. I am a strong believer in the ambiguity of the photographic image. I think the very same photograph can present both a truth and a fiction. All of my photographs do just this. They are the truth, but they are not all truthful. I am photographing memories, but they’re not my own. I think of my photographs as a time machine.

October 18, 1860 © Stacy Renee Morrison

You are fortunate to have Sylvia’s letters and journals to draw from. What’s it like to read someone’s diary from the 19th century?

I have to say that I just marvel at the endurance of these little books, standing the test of such a great distance, time, and energy to find their way to be here in the present. These books are Sylvia’s testimony. I knew I needed to take great care of their memories, because Sylvia was telling her own story in her own words. She filled nine diaries spanning the period of 1858 to 1869 and the books are really tiny. I think actually, I am in progressives because the penmanship is so small!

I have to admit, at first I felt hesitant to read such intimacies. I wondered if I was disavowing some set of inherent privacy codes; ones that clearly demarcate that you do not read other people’s journals or letters. It’s surreal to read Sylvia’s day by day accounts, knowing what I now know of her life. When she writes in October of 1860, I already know what’s going to happen to her in October of 1866, and it’s peculiar to have this omniscience with someone else’s life, so to speak.

That sounds a little ominous, did you discover anything really personal or tragic that happened in those later years?

Some of her very personal passages are frustratingly vague because of what was left unsaid. There’s a passage from January 27, 1862, and it says, “This house is enough to set one wild, Annie has an elegant new silk. I have nothing.” I wonder what this means.

Then there are some sentences where she expresses her grief and rage, that are so deeply felt that I have to put her journal down and close my eyes for a few minutes. Sylvia was a survivor of domestic violence in the 1860s. Her husband was an alcoholic, and she writes in her journal how he beat her and their young son, William. I grievously witness her pain, her sadness, and fear. But in her journals, I also learned about her strength and resilience as she strives to protect herself.

What did she do to protect herself? What options did a woman even have in her situation in the 19th century?

Although divorce was technically legal, this action was not deemed acceptable for a woman, especially a woman of her social class. If she pursued this, it would have meant social devastation. Sylvia also had a terrible relationship with her father and could not turn to him for support. Marriage was essentially the only way out of his household, but sadly it only left her in another precarious situation. A month after they were married, Sylvia already writes about William’s abandonment and abuse. He didn’t come home on their first Thanksgiving, and she would soon consult others about help with financial affairs. After his death, she wrote a letter to William’s family asking for help. These gestures of self-preservation are significant, and when I read her journals, I wish I could have been there to help her.

October 18, 1860 © Stacy Renee Morrison

You mentioned that Sylvia keeps a journal from the late 1850s to the late 1860s, and that of course coincides with the American Civil War. What, if anything, did you learn about her politics during this period?

I wish Sylvia expanded more at certain points and mentioned the Civil War or other current events, but the only time that she mentions the war is when she’s attending a funeral for someone she knew. She writes exclusively about what’s going on in her own world, which certainly was not uncommon for a woman writing in a journal. I also bring up the point again that she only had room for one sentence a day in these very small books.

However, through my research, I encountered a part of Sylvia’s story that contains the horrific and inhumane history of slavery in the United States. Her great-uncle James DeWolf and her maternal great-grandfather John DeWolf were slave traders. James DeWolf was the main architect for the business, and he made a fortune from it. I do not know what, or even if, Sylvia knew about her ancestor’s involvement in the slave trade. She was born after her great-uncle had died and was an infant when her great-grandfather passed away.

I can’t help but wonder if Sylvia did know this history in full, and how she reconciled herself with this information.

I have often wondered about this as well. I think about what she may or may not have known. I ruminate on the evidence, and the answers are inconclusive. She left no record of her thoughts that still exist. I looked to her contemporary descendants for answers. In 2008, Katrina Browne, a descendant of James DeWolf, produced and directed a documentary that was shown on PBS called Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North. This film follows ten DeWolf descendants as they retrace the triangle trade and examine this part of their family history. It’s such an important project, and I hope projects like these continue to bring meaningful dialogue about the atrocities of the past into the present.

What strikes me about the documentary is that it addresses the DeWolf family’s long-held silence about their heritage, which they’ve described as a secret hiding in plain sight. More recently you’ve turned to your own family history for another project, and it also deals with the erasure of history that occurs between generations.

Yes, in 2015, I began another biographical quest, originating with a photograph in my grandmother’s album. I was always close to my maternal grandmother. She arrived in the United States from Poland in 1927 when she was 13 years old.

I would always ask my grandmother about Poland and her childhood, but she would never speak about the past. Whenever we looked at her albums, the page would quickly turn when we happened upon one particularly beautiful sepia toned photograph of a mother, father, and son. The woman in the picture, with her sullen and penetrating dark eyes, pierced me.

I later learned that this woman, Sura, was my grandmother’s oldest sibling. She stayed in Poland with her husband and children to take care of the family bakery. Eighty-eight years after my family left Poland, I returned there. I stood in what was most likely the bakery that was taken from my family. I walked the perimeter of the Warsaw ghetto, where I learned that Sura was imprisoned. I discovered that she died there on February 20th, 1941.

Did your grandmother’s family know of Sura’s passing?

This is a hard question to talk about. They eventually would, but I don’t know when they learned this information exactly. I often watch this film of my grandmother’s wedding. It’s three minutes long and it was made in June of 1941. I think about this joyous family event, which took place only a few months after Sura’s death. My grandmother, her brother, their wives, my great-grandmother, and the extended family are all posing and smiling in front of the synagogue. This eight millimeter camera is whirling away on apparently a very windy afternoon in the Bronx, because all of the women are holding on their hats. I do not know if the family even knew that Sura was dead, and this haunts me.

I never thought that my grandmother was intentionally erasing history. I think she was trying to mute her pain from her past and insulate me.

And this silence is something that you’re addressing in your current work?

Yes, I have now expanded by searching for the life of another great-aunt and I also met her through a photograph. The moment I saw this beautiful woman, my heart wrenched because I immediately understood when she died. Her name is Tunia, and the title for the work devoted to Sura and Tunia is Half-Way to the Rail Station in the Hot Summer Weather, which is a reference from an essay written by Virginia Woolf about her great-aunt, Julia Margaret Cameron. I loved that because they were the most famous great-aunt great-niece reference that I could think of.

This series encompasses photography, video collage, and silk screen. It’s about two women out of six million Jewish people who died in the Holocaust, and it’s my intention to give them presence because of their absence.

Half Way to the Rail Station in the Hot Summer Weather © Stacy Renee Morrison

Did your practice change when you started to occupy the space of your own ancestors, and how is that different from your experience inhabiting Sylvia’s life?

Finding Sylvia in death was romantic. The only connections we have are the ones that I would create for us, through my work. Losing my great-aunt Sura to a death so horrible is painful. The blood running through my veins is the same as Sura’s. Family wounds differently.

Why are you drawn to photography specifically as a means for giving presence to the past? Why this medium?

I think photography has been readily understood as a medium for capturing what one sees, but I do not believe this. I use the camera to create what I cannot see. All of my work is based on certainties that I have learned about these women’s lives. But I also have to use my imagination to fill in the gaps and express what has been left unexpressed, unrecorded, forgotten.

My objective is for my photographs to dissolve time. I hope my work is successful and that it shows that memory does not die. I believe photographs are ghosts.

The idea of the photograph as a time machine and a ghost is such a striking metaphor. Earlier you said that your projects begin when a dead woman asks for your help. What do you think they’re asking of you?

I still do not know the answer to this question with any certainty. I guess what happens is that I see these dead women as my collaborators. They are my muses. I am their medium, in a sense. They tell me things, or do not tell me things, and then I find the answers in my work. I form the bridge between what is left of them from their world and what remains of them in mine.

What do you learn about your own life by immersing yourself in theirs?

I had this great epiphany while working on The Girl of My Dreams. It was that Sylvia was a bolder woman in the 19th century than I believe I am in the 21st century. Early on in this project, I would sometimes introduce myself to strangers as Sylvia. I think Sylvia infused some necessary bravery in me. When I was pretending to be Sylvia, I felt fearless. These experiences helped me feel more self-assured asking for something I deserve, or simply standing up for myself. I feel like I inherited her confidence, and because of Sylvia, I understood how to be a stronger Stacy.

What about your great-aunts? What are you learning from them?

Those questions make me sad. My great-aunts’ stories are grimmer, somber, more heartbreaking. I also know a lot more about Sylvia than I do about them, so when I immerse my life in theirs, it’s both more personal because they’re family, but also more abstract. When I think of Sura and Tunia, I think about their lives ending as some nightmare, and the nightmares I’ve had all my life about the Holocaust, and I’m scared. I wonder what they would think of me in my life today. I began this project almost at the exact age when Sura died so tragically. I think about if my own life were cut short, and I think about how many things I still hope to accomplish, and do in my life, and the things that she never got to do in her own life.

It sounds like these two projects counterbalance each other emotionally for you. Maybe Sura and Tunia’s story opens you up to tremendous vulnerability, and Sylvia provides you with the resilience to address that vulnerability and make something from it?

I know that because of these women, I live more fully. Inspired by them, my days are filled with creativity, because of them I strive to enrich my life with diverse experiences. The way life is lived is to the very second, in the present. We may be hopeful for the future or contemplative of the past, but we click through existence in the moment, which now. Saving these women from obscurity has given my own life more meaning.

Sylvia’s Dresses © Stacy Renee Morrison

Stacy Renee Morrison Recommends:

-

The Merchant’s House Museum on East 4th Street in Manhattan. It is the best place in New York City to time travel. When you are in the house you feel as though the former occupants, the Tredwell family have just stepped out and will be back at any moment. I especially recommend the 1865 funeral re-enactment that the museum holds in October.

-

The photographs of Lady Clementina Hawarden. She photographed her daughters in London in the 1860’s. Her portraits are exquisite.nThe dresses, the wallpaper, the poses, the sunlight. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has some of her stereoviews on display. These are gorgeous in person.

-

Stories We Tell the 2012 documentary by Sarah Polley. This film explores subjectivity, objectivity, fact and fiction in considering the past. I do not want to say too much to spoil it. All I will say is that it is simply amazing.

-

I love reading biographies, letters, diaries and histories about 19th century women. This is what fills my bookcases. I recently read The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper by Hallie Rubenhold. She humanizes these women who have been both mythologized and demonized in the historical record. Both the scholarship and compassion in this book are of great note.

-

The 40 Part Motet by Janet Cardiff. There are 40 individual speakers set up playing a recording of the Salisbury Cathedral Choir singing Spem in alium composed by Thomas Tallis in 1556. It is so simple, but the results are so complicated. It makes me cry every time I see it. If this installation is ever near you, please go see it! You will thank me.

- Name

- Stacy Renee Morrison

- Vocation

- Visual artist

Some Things

Pagination