On finding a home in punk rock

Prelude

Cristy C. Road is a Cuban-American artist, writer, and musician. Road self-published Greenzine for 10 years, and has released three illustrated novels addressing gender, sexuality, mental health, and cultural identity: Indestructible (2005), Bad Habits (2008), and Spit and Passion (2013). She is the creator of the Next World Tarot, an illustrated tarot deck depicting resilience and revolution, funded on Kickstarter in 2015. Her illustrations have been featured in New York Magazine, The Advocate, The New York Times, Bitch magazine, and many more. She fronted the pop-punk group The Homewreckers for eight years, and currently fronts the band Choked Up. Road has been touring on her own, with her bands, and with Sister Spit: The Next Generation since 2001. She is a Gemini and lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.

Conversation

On finding a home in punk rock

Artist, writer, and musician Cristy C. Road discusses making art in service of social justice, writing about queerness and trauma, and her advice for zine makers.

As told to Rebecca Hiscott, 2916 words.

Tags: Music, Art, Writing, Activism, Inspiration, Mental health, Independence, Day jobs, Politics, Adversity.

On staying grounded and engaged

The world has been influenced by terrible people in power for so long, so there being a global uprising [right now], to me, is just heartwarming. I’m participating in the way I have for the last 20 years: with art and protest.

I couldn’t go to any protests [recently] because of my injuries. I couldn’t walk for a minute. I had swollen lymph nodes on my neck. I was waiting for coronavirus results. I wasn’t going to go marching when I had weird stuff that I didn’t know what it was. I didn’t know how to protect other people from it. I just had to disappear and focus on work and focus on what I can do creatively—sharing tarot decks, for example, or doing more intentional art and fundraisers, supporting the Black spiritual witch community.

Even though before the tarot deck everything I did was memoir, it was political—especially doing it 20 years ago, when nobody wanted to listen to stories about healing from violence and all that stuff. I have always been hiding in my house, making art for causes that I think need to be elevated.

The pandemic is this whole experience of safety and protecting other people. I miss concerts and playing music and watching music. It’s really sad, but it’s like, there’s a thing going on, and we need to protect people. We need to keep people safe. Just believe that you’ll be able to reconnect with the things that bring you joy, such as music, and relating, and dancing, and touching people, and meeting people. But for now, you have to focus on something else and not be constantly mourning that life. Try to build a life that can accommodate what’s going on in the world.

My life is kind of the same. I work from home. I keep grounded by going for walks. I really like going running. I try to do these super normal things because my brain and my work and my livelihood is so much about expression and chaos and articulating my traumas and articulating my love and fear and pain.

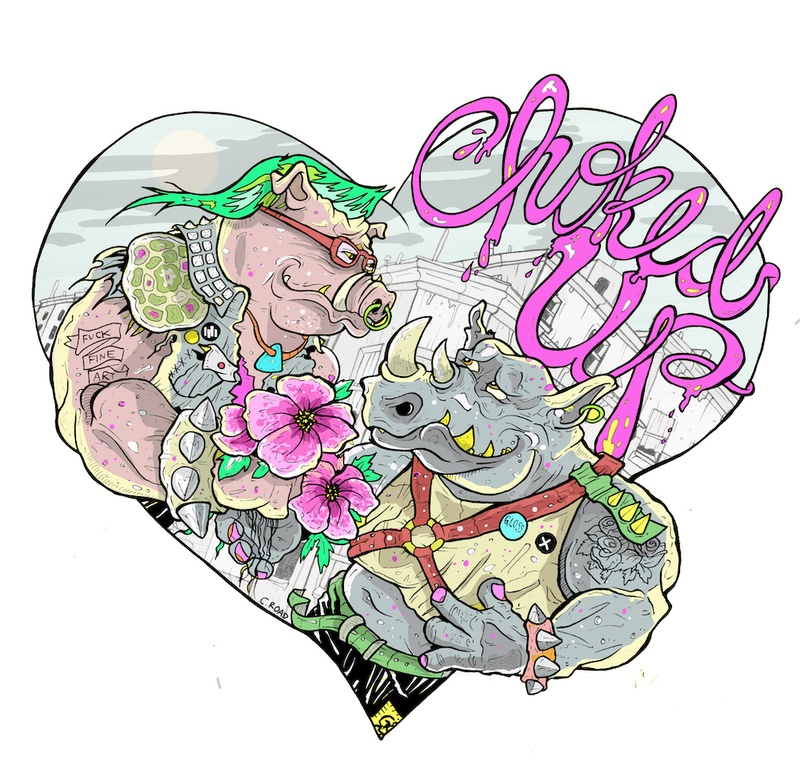

BeBop & Rocksteady Together 4-Ever (ink, digital) 2018

On making money

[My work] hasn’t kept me financially stable for most of my life. I’ve been to a bunch of art schools. I have an MFA. I like teaching, but a lot of those jobs never pan out. I don’t get them. I’ve been cocktailing for a very long time. I’ve had all kinds of jobs. I don’t care because it’s just making money to pay the bills.

My priority has always been jobs that allow me to have a couple days a week that I can focus on my art and my music because I need to do that, because it’s a voice. I need to express myself. I hope a lot of people are keeping grounded by making things and figuring out what they want to make in the world that isn’t about making money.

Growing up and seeing my family and the people in my life, in a working-class community where everybody had either a stable job that they worked really hard to get or a couple jobs, it was like, passion and what you have passion for, and capitalism and surviving under capitalism were these two really separate things. Money was a separate thing, but it was necessary to survive and to live and to deal with your health, especially in America.

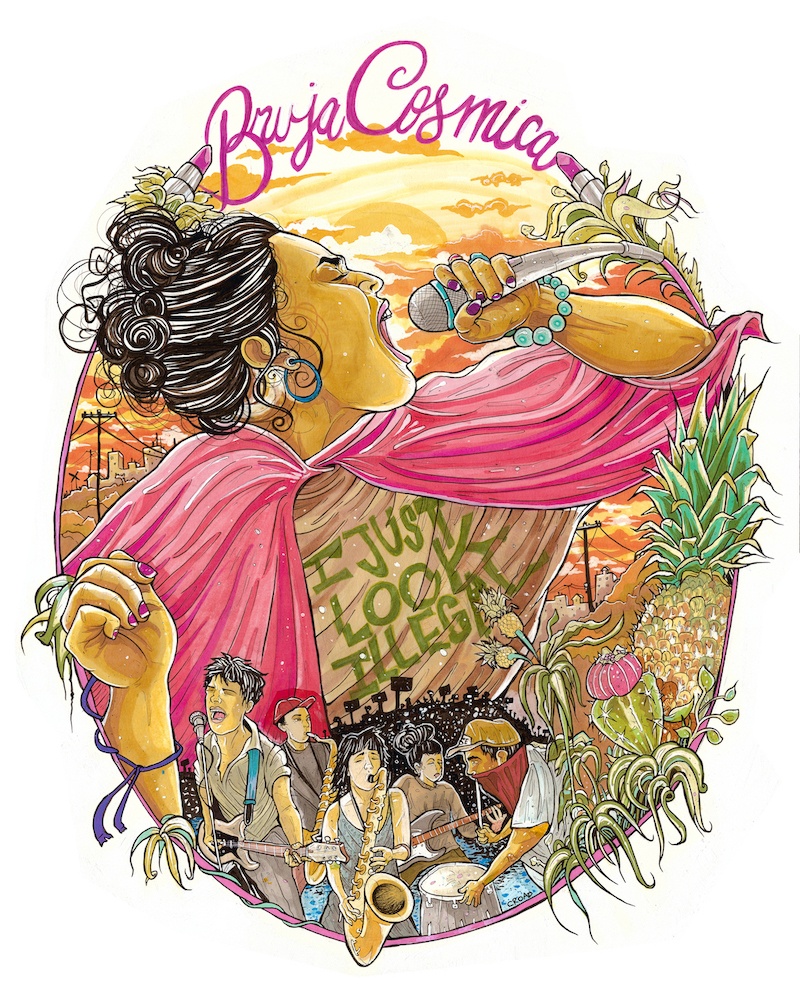

Sobrevivr: Victoria Ruiz of Downtown Boys, Malportado Kids (ink, marker, white out, gelly rolls) 2015

On finding a voice and a community

When I got into punk rock, I was able to articulate these ideas as expression, sharing, making art for educational reasons, for revolutionary reasons, and just for letting out anger. Existing in a community where you’re pissed off, you’re sad, you’re hurt, you’re mad at patriarchy, you’re mad at homophobia… This was the place where you were allowed to be mad at those things. Punk rock, to me, was always about revolution, and feminism, and queerness, and anti-racism.

I was about 18 when I realized I was getting kind of famous. My zine [Greenzine] had a distribution of about 500 copies. I was so young, and I was doing it all by myself. It was so cool that people gave a shit about what I had to say. It all started as a Green Day fan zine, and then through Green Day I got into queercore, and it became this feminist, pop punk… It was just all these punk things that I liked that didn’t like each other. There was tension between the riot grrrl scene and the pop punk, Southern California scene.

In the ’90s, in Miami, there was this war against nerds and rockers. We were all made fun of by jocks. Jock culture and money and capitalism and fame were so revered by a lot of the kids that I was around in my school and in my community. Rock and roll and punk was what really held me, because it was the only place where I found angry gay people and angry women and angry people who just looked messy and weren’t really taking care of their complexions or teeth. I was like, “This is where I belong.” The whole community really held me for a very long time.

On authenticity

Those punk ethics are very important, but at the same time, I definitely needed people of color and queer community and artists who were not punk and didn’t have that, “Fuck money, let’s survive in this underworld that we are creating because we’ve never had money, and it’s evil, so fuck it” [mentality]. You get old, and you have to have health care, and you have to pay rent. You have to survive.

I moved to New York City because it felt like one of the only places that was safe to be queer and experience my life and feel free and not have to look a certain way, dress a certain way, deal with my body a certain way. I’ve been chasing this my whole existence, trying to have this anti-capitalist way of living but then also being like, “You know what? If I get a deal that’s going to pay me well and let me use my voice and be who I am, I’m going to take it.”

My whole zine started because I loved Green Day, and I loved the community they were coming from. I hated that they had all this backlash. If you work really hard and you grow up really poor, and then a record label offers you a deal, yeah, it’s complicated. It’s going to open the gateway to this sacred world.

Our community is so sacred and there’s so much belief in it. But then there’s a lot of denial of certain privileges and certain lifestyles. Like money. I needed feminism and communities of color to be [able to be] like, “Listen, I’m poor as fuck. I’m not going to judge somebody for using their money to buy some bougie soap that is SLS- and paraben-free and made out of leaves.”

Muse: Grace Jones (ink, marker, white out, gelly rolls) 2020

On writing about queerness and trauma

I remember there was this joke in the community about how if you cut up a Green Day sticker, it can say “gay nerd.” So I made this article, which was the only article in the whole [second issue of Greenzine] that wasn’t about punk. I didn’t come out in it. I think I even started the article like, “Everyone, I’m straight, but we should love gay people.” I remember being very paranoid about being out until later in the zine.

I remember writing about how all the Green Day fans and all the rockers at school get called homophobic slurs because we dye our hair and wear jewelry and stuff. Everybody participated in it. Nobody was stopping homophobia. Everybody thought it was such a joke. It was just so in my face, I needed to write about it. Women in my community were always calling me gross because they heard from someone that maybe [I was] gay. Writing about it as it was happening, writing about the stuff that was happening to me, was really hard.

As time passed, I started reading more personal zines, namely Doris, the zine by Cindy Crabb, and also a lot of the lyrics of riot grrrl bands about sexual trauma. It made me think about writing about trauma and writing about homophobia. It pushed me to examine how I was healing, and I kind of realized that I wasn’t. I was holding on to that trauma and acting like I had healed from it because I had found anarchist punk, and zines, and DIY. I had found folk punk and this magical world of anarchists, anarchical feminism and queer feminism. It was a good space to be broken. There were so many of us who were broken, so it was so important for us to have each other.

That’s [also] when I was in an abusive relationship with somebody I loved. We were open, poly, and everybody’s dating each other, so everybody had trauma with the same person. That trauma is what really pushed me to tell really vulnerable stories. I wrote two zines about it. For the first one, I had other survivors write about their situations with the same perpetrator.

Then, the next issue, there was a lot more about racism. I started realizing how I was in a lot of support circles where I was the only person of color. I started writing about that because it was easy to write about this stuff in this scene. That’s what we were thriving off of—telling the most vulnerable and intense stories, and educating each other, and growing, and having intense house meetings where everybody is crying about intersectionality. This is 2003, 2004. It’s just this era of healing.

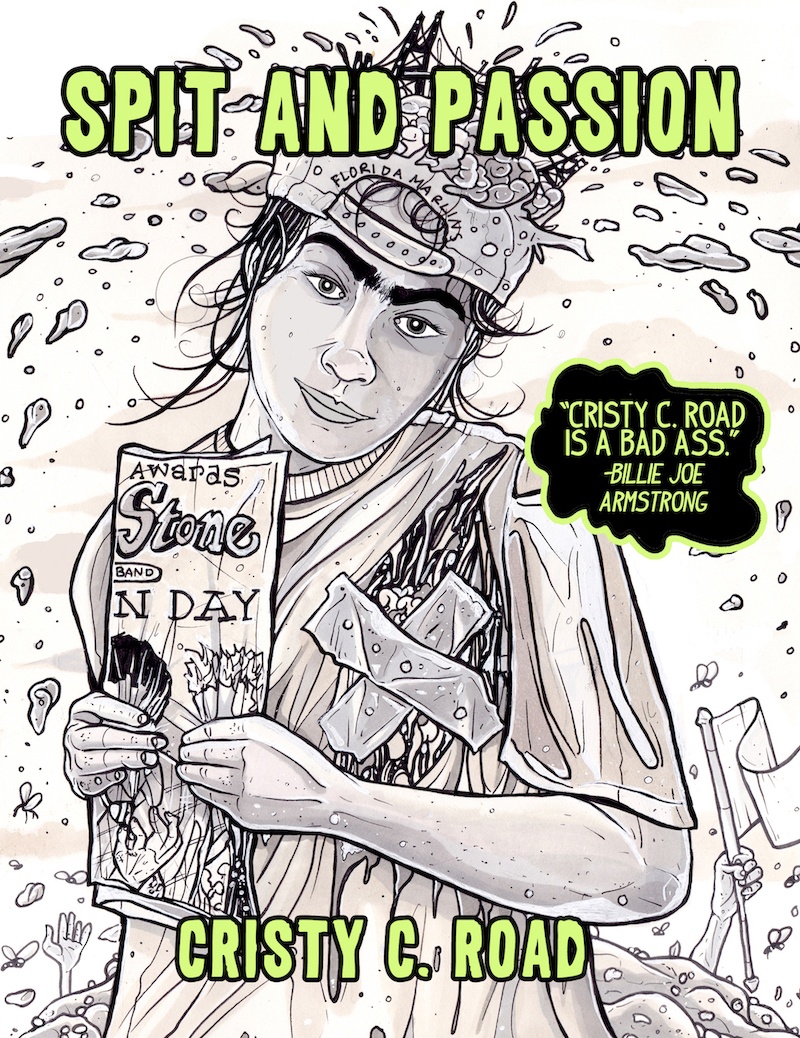

Cover Art from Spit and Passion (ink, marker) 2012

On healing

My first novel was Indestructible. That was the first time that I traced back. I wrote about the past. I was able to articulate all of the sexism, homophobia, all the stuff that I didn’t write about in Greenzine as I was experiencing it because I was young and didn’t know how to articulate it, writing about being queer and not knowing what that means, and writing about the really traumatic stuff my friends were experiencing. There was sexual assault, there was death. The story’s super fictionalized. I don’t mention Green Day on purpose because I really wanted it to be fictionalized. Then, after that, [I wrote] Bad Habits, where I wrote about the folk punk scene and the abuse, and then moving to New York to heal.

Sexual trauma affects how you love, how you spend your money, how you deal with your body, how you deal with your health. [Healing] has been these really long steps that lasted for a very long time. I definitely feel like I have healed so much, and I feel like a completely different person.

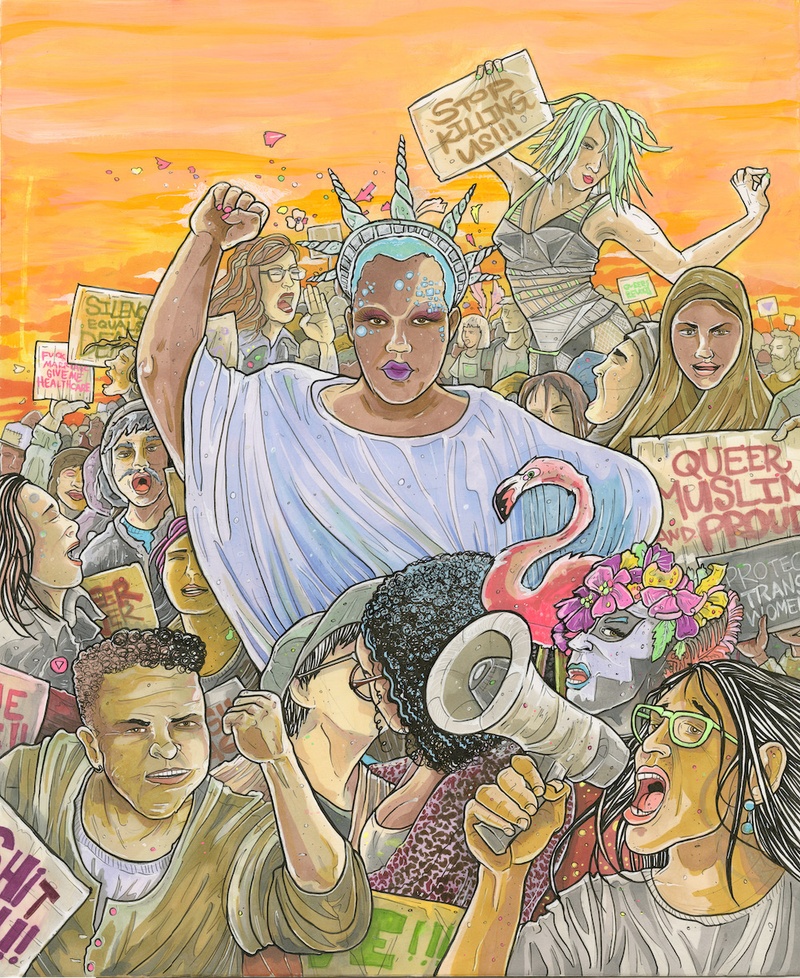

Next World Tarot: Justice (ink, marker, acrylic paint, white out, gelly rolls) 2017

On tarot and ancestral magic

When [my third memoir] Spit and Passion came out, the opening night was at the Brooklyn Museum for First Friday. It was an amazing release. But I was just so sad. I was so checked out. I only cared about finding love. I was trying to rehabilitate a relationship that had just ended. It was my Saturn return. I didn’t care about my work, I didn’t care about the music I loved, I didn’t care about punk. I didn’t care about activism. My brain was not present. I was touring with my art. I was touring with Sister Spit a lot. I did so much cool stuff that I was not emotionally present for because I was still healing.

But then it became better. It was like, “Okay, I’m not present. I’m not super proud of the work I’m putting out. But I’m doing ancestral rituals, and I’m doing so much reconnection to my ancestry and to my magic. It’s pushing my tarot deck into this whole new territory. It’s changing me as a person.”

Tarot is this whole community that I’d never been a part of. I’ve always been a punk and an activist and a feminist. When you’re a queer woman of color, witchcraft becomes this path that you share with so many people who have similar experiences. Doing a tarot deck, it’s not a memoir, but it’s with all my friends and all these people I admire. I still feel like it’s such a big, personal piece because it’s all of my political values.

I think that queerness is so old and ancient, and colonization is what made it an other. The concept of gender queerness is part of a lot of magical people. Once I learned about this power that comes from a different place, other than making things, this power that comes from your body and your mind connecting to ethereal realms and the past, connecting to symbolism, connecting to synchronicity… It’s the only way that I can feel grounded and not like this parody of myself as a zine maker in the ’90s, you know? It’s the only way that I feel like I can keep growing. I don’t just feel like this punk who’s constantly reinventing herself. I feel like this healer or this culture creator. It’s hard to stay there because of imposter syndrome, but it’s nice to find myself there every now and then.

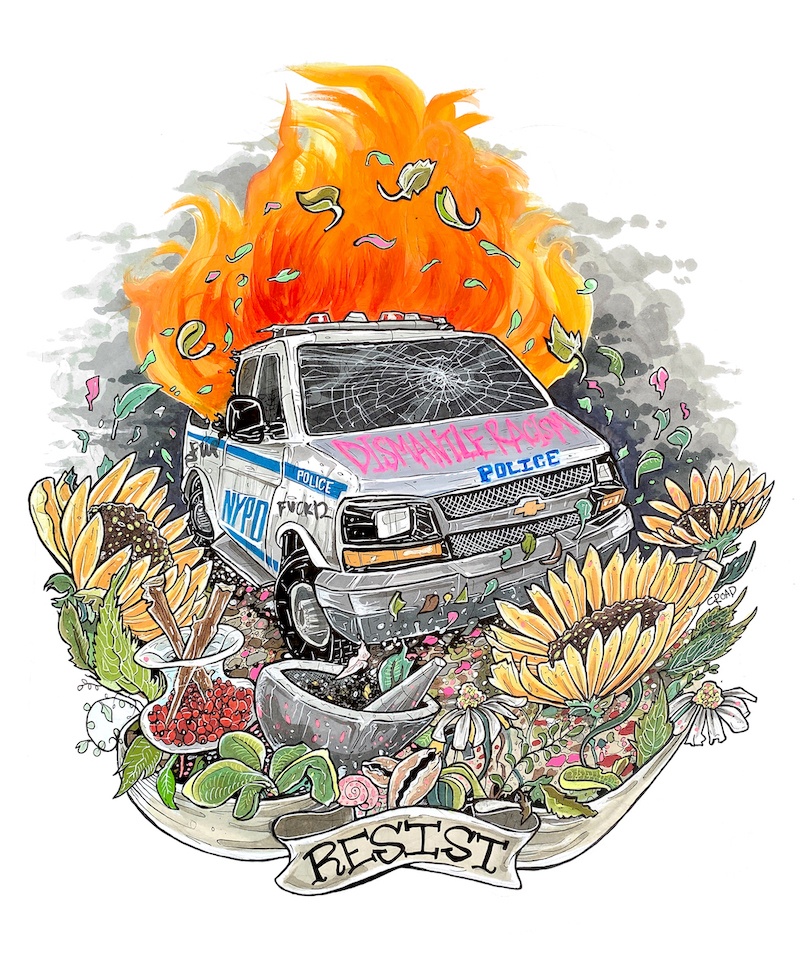

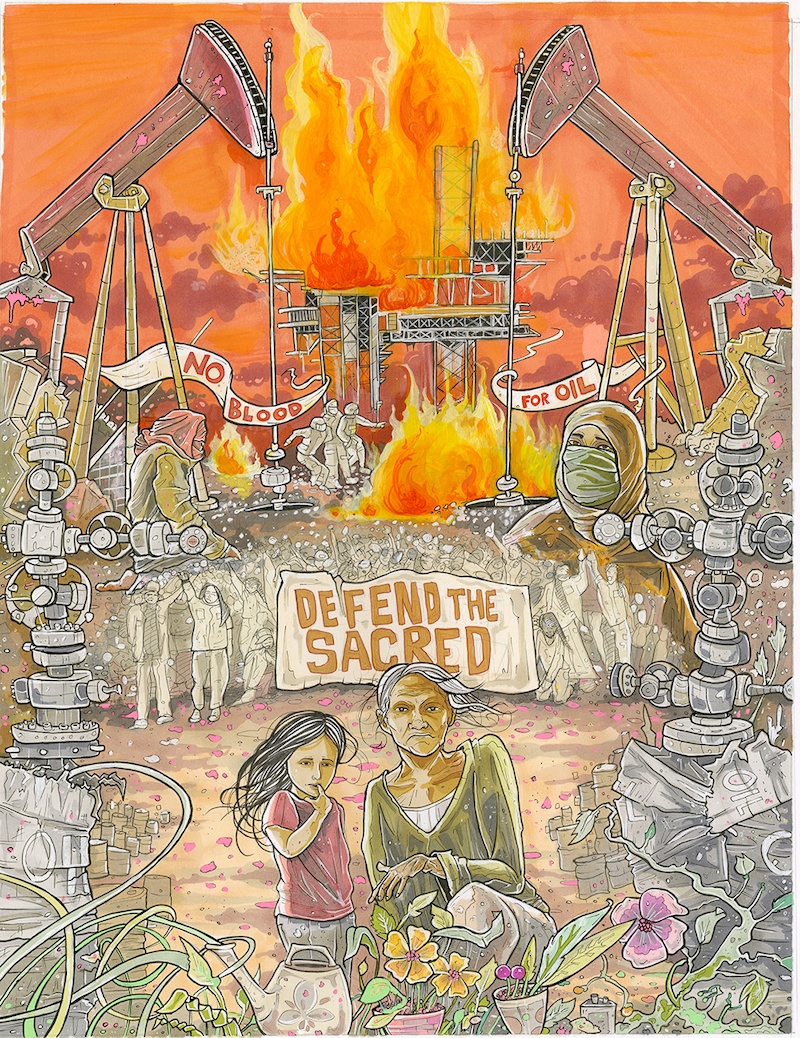

Resistance Ritual (ink, marker, acrylic paint) 2020

On her advice for zine makers

Tell your story when you’re ready. Participate where you feel passionate, because the point of zines was always just to get a story across. Punk didn’t invent zines. There have always been mediums of self-publishing, like the way the Black Panthers survived and the way revolutions have survived in the underground. You have to communicate in these other worlds. That’s what’s beautiful about them.

Feel as free as you can and be as informative as you can, because it’s also a privilege and an honor to print on a page. Tell the story you need to tell and use the layout you want to use. If you really want to be informative, straightforward—like, this is a checklist for street medics, this is a zine that we’re going to hand out at the protests, this is a legal observer zine with all the phone numbers that we need… Those zines, I think they should be small. They should be, like, quarter size. They should be typed on a computer in Times New Roman or Courier or Arial. These zines that share really important information to keep us safe, I don’t think they should be as “fun” as an art zine or a poetry zine.

That’s the only guideline. Because if you’re doing a zine that’s for entertainment—you’re interviewing bands, you’re writing about your day—or a zine that’s really personal, like you’re writing about your trauma, you should allow yourself to be your own layout artist and do it however the hell you want. If anyone’s going to be like, “But that’s so messy and that’s so weird, and that doesn’t match,” it’s like, well, fuck you, then. Do your own zine that matches.

Next World Tarot: The Tower (ink, marker, acrylic paint, white out, gelly rolls) 2016

Cristy C. Road Recommends:

Dookie by Green Day. It’s the Green Day album that changed my life. You should listen to Dookie and then the brand-new album [Father of All Motherfuckers]. Listen to both of them together.

Homenaje a Los Santos by Celia Cruz. Celia Cruz is this badass witch who has all these songs about Santeria and her West African spirits and her ancestors and the people who gave her the power to be this fucking queen of Cuba.

Germfree Adolescents by X-Ray Spex. They are a very important punk band. Poly Styrene is the singer and one of the first women, Black women, fronting a punk band. Just listen to everything she has to say.

Half Fiction by Discount. Discount was the first woman-led pop-punk band that really changed my life. I love these songs. They’re like really long poems.

Assata: An Autobiography by Assata Shakur. It’s another thing that bridged the gap in my life between being Cuban [and] American, connecting with the people on the Cuban island.

Theresa Chromati. I just discovered this artist. I’m obsessed, and I want to spend a bunch of money buying her stuff. She’s a painter. She does murals, these beautiful colors and these beautiful, abstract images of bodies and of people, representing her culture, her gender. She’s just a badass.

- Name

- Cristy C. Road

- Vocation

- Artist, writer, and musician

Some Things

Pagination