On the value of intentionality

Prelude

Alysia Mazzella is an artisan candlemaker based in New York.

Conversation

On the value of intentionality

Artisan candlemaker Alysia Mazzella on a slow, considered process, rooting in nature, and fostering regenerative relationships.

As told to Adrian Inglis, 1794 words.

Tags: Craft, Art, Process, Inspiration, Beginnings.

On your website you write “The heart of our studio is a pot of 100% beeswax. This is where the magic happens, where the sun-struck wax fills the air and time moves slow.” How did that wax pot end up at the heart of your studio, and what brought you to beeswax and candle-making?

I started by burning candles first, and I was burning any old candle. I realized that I didn’t know what my candle was made of and that sparked my interest. I was in a space of making a lot of things and candles were the next thing. I had some beeswax on hand, melted it down, and dipped my first candles. As far as the quote, wax going into the air and time moving slowly felt very ancient; burning candles feels primal. Making them also reflects that slowness and the time it takes to actually hand dip layer by layer versus pouring. I love the relationship of wax and air and how the wax disappears and transforms.

Do you burn candles while you’re making candles as a way of holding time?

Yeah, I usually do. I think it’s the element of intention and saying, “This is what’s about to happen,” and then you light the candle and hold that energy.

I think a lot of people use candles in sacred ways, sometimes even without realizing that that’s what they’re doing.

For sure. Even the candles we talk shit about, like the soy candles, they’re still very ceremonial. My mother-in-law lights them as an air freshener. She’s freshening and literally cleansing the air, cleaning the room and the environment, and that’s what it is. It’s like, “I’m doing this now.”

That’s such a nice way of looking at it, it’s easy to hate on less natural waxes like paraffin wax.

I mean, it fulfills the same purpose, right? I feel you. I’m a beeswax snob, obviously. But I think it’s all the same. It’s just like any kind of technology. I’ve even seen some candles that are literally battery operated, and you can dim them. I think that speaks to how important fire is to us, that we’ve gone to the lengths to make it not fire, but still emulate fire. If anything, it speaks to how powerful fire is.

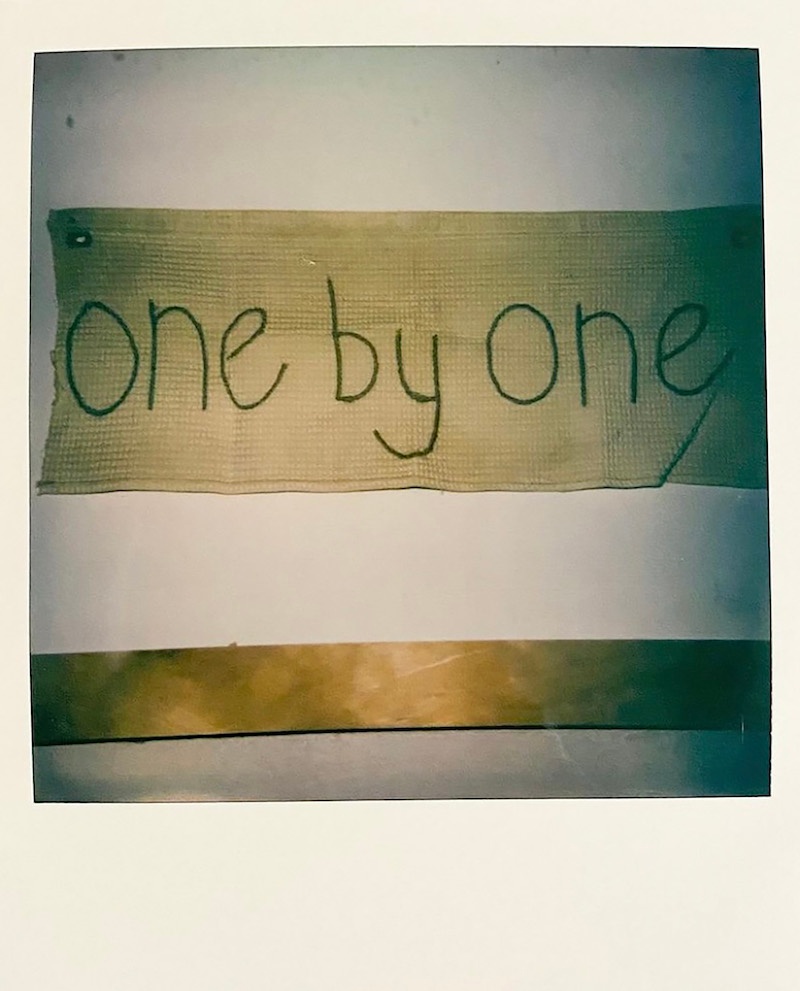

I have seen the phrase “one-by-one” come up in relation to your work. Could you talk about the importance of slowness and intentionality in your process?

That phrase is inspired by doing things by hand and individually, versus mass-produced. It’s a response to our box-store culture. And it’s not an activist response, it’s just truly what feels good to me. I think the element of getting a single piece of braided cotton wick, and pulling that off the spool and cutting it to size for that individual candle, and then doing it again for the next candle and the next candle and dipping one by one, the individuality of it feels so good. That’s really what I mean by one by one—there’s a living energy in each individual piece because there’s nothing mass or quick about it. They’re original. They’re like us, like humans. I think that’s what gives them this aliveness. That’s what one by one really means to me—the aliveness of each form.

You spoke about the ancient and primal pull of candle making—could you talk about the importance of honoring the past and the tradition of your craft?

Someone recently said to me, “Oh, you’re a candlemaker. Do you think any of your ancestors were candlemakers?” And then I thought, “My mother’s an accountant, and nobody asks her if any of her ancestors were mathematicians.” I think specifically for candle-making, it is just human. So yes, ancestors, but truly just human ancestors.

I think candles activate something worldly. All of my candle forms pay homage to candles that have been around for a very long time, like the Mexican prayer candles I call Glass Pillars. Mexico is definitely one of the cultures and countries that have a very tight relationship with candles that hasn’t been broken. You could walk down the street in Mexico, and there’s shrines for Guadalupe containing candles. I remember when I first started making candles, someone I know who is Mexican said her grandmother used to always burn the seven-day prayer candle made from beeswax. She said she’s never been able to find them at the Santeria stores in the hood or anything because they’re all made from paraffin wax now.

Traditional candles tend to have been made from beeswax and natural wax because candlemaking wasn’t a big production, people made candles for themselves or their community. Candles have always been very small batch. Even the Twin Flame candle, is a candle from Italy, traditionally called a duplero, which means duplex or double, but I just found out, from another candle makers website who is based in Europe, that the duplero is actually inspired by the narwhal whale tooth. And that, for me, I was like, “Yes.” I was rooting in this Italian tradition, but they’re rooting in nature, and that beauty and that biomimicry. It’s simple.

As for honoring tradition, I want to make candles that actually burn. Candles now are not only made from waxes that are probably not great for us to breathe, but they also are made in forms and shapes that don’t necessarily burn well. Candles are beautiful and fun, and you should definitely do whatever you want to do with them. But for me, the traditional element is like, this candle burns for this amount of time, for example the tea light, that comes from Japanese tradition, and that was meant as a timekeeper. It burned for two or four hours. It kept the teapot warm, and also, once it went out the tea ceremony was over. So I love that element of candles too, of when they burn intentionally or in a specific way, they hold time and space.

You use the term “regenerative relationship” with the honey bee. Could you define what a regenerative relationship with bees and nature looks like for you and why that’s important?

I was making candles for about four years before I started keeping bees. I wanted to keep bees because they’re so interesting and because I’m in a relationship with bees and using their byproducts almost every day. I live in upstate New York, and saw a lack of diversity in this world when I would buy beeswax to make candles. I felt there was something missing in my life, which is honeybees, but also there’s something missing in beekeeping in upstate New York, which is diversity. And not only in race, but also in age. It’s a lot of elders that are keeping bees. I thought, if I’m going to keep bees and I’m already purchasing so much wax from other people, I want my beekeeping to be for something different. I was like, “What can I do for the honeybee? Look what they’re doing for me.” And the only thing I could really see that made sense at that time was an educational apiary. So that’s how that idea was born. The land is called Backland, and it’s a garden and an apiary where we gather. We’re very young, only in our second year, and I’m still trying to figure out how everything fits together.

Right now we’re having annual courses, one for beekeeping, one for land work. And they’re about that relationship of being with the bee, but not for any specific outcome other than for their wisdom, protection and friendship. It’s really fun. It’s about being in a relationship with the bees without needing something from them. Sometimes they’re literally overflowing with honey, and they have no more space, and you have to take honey, which is awesome. Many beekeepers give their bees sugar water, and we all know that sugar isn’t as good as honey. So I’m practicing that regenerative relationship with the bees. They should be eating their honey, and once they do well and overflow, then maybe we can have a piece.

It’s about making sure they have what they need, giving to the bees rather than just taking. Honestly, just being in their presence is enough. I’ve heard so many people talk about this. There’s something about these creatures that we’ve been so obsessed with for thousands and thousands of years.

That’s a great framework for an educational workshop “We’re not here to extract anything. We’re just here to be with the bees.”

Yeah. It’s about spreading that love, too. Introducing people to bees who may have never met bees or maybe have a misconstrued idea of bees, because our media does their own thing with them. And I think that’s part of the regenerative relationship too, helping other people fall in love with bees and seeing a relationship they could have with them.

What was it like to make the shift from living in the city to living rurally? Are you happy you made that move? Does having workshops help you find community in a less densely populated area?

It was a shocker but there’s a lot to gain from the space and alone time that rural living provides. I am happy that I made the move. Having gatherings and showing up as community is very important when you live in the middle of nowhere.

Okay, so I’m gathering that you have a lot going on. You’re a beekeeper and a candlemaker, and you have a farm, and you organize workshops. Could you offer some insight into how you balance these things?

I am learning. That’s the first thing. On top of all that, I became a mother, and that’s the thing that throws you for a loop, because you’re always on call and there is no respect to any schedule. I guess everything kind of fits together in a very natural way if I let it and if I do my part of sitting and reflecting and thinking and envisioning and staying on the path. I just try to fill myself up the best I can. It’s day by day.

- Name

- Alysia Mazzella

- Vocation

- candlemaker

Some Things

Pagination