On taking the long road

Prelude

Jeremy Sorese is an artist based in Brooklyn, New York. After graduating from the Savannah College of Art and Design in 2010, he was accepted to La Maison des Auteurs, a comics residency program in Angoulême, France, where he worked from 2012 through 2013. His first book Curveball, published with Nobrow in 2015, was nominated for a Lambda Literary Award. A sequel, The Short While, was published with Archaia in November 2021. He’s been teaching art for 11 years; Elementary School children in Chicago, Middle Schoolers in New York, college students at the Maryland Institute College of Art, and most recently at The New School as well as School of Visual Arts.

Conversation

On taking the long road

Cartoonist and artist Jeremy Sorese discusses the importance of specificity, safeguarding the joy of making work, and not rushing through the process.

As told to Mitchell Kuga, 3158 words.

Tags: Comics, Art, Process, Success, Focus, Money, Identity.

Both of your graphic novels, Curveball and The Short While, take place in sprawling science-fiction universes with many moving parts. In thinking about tackling something so big, what comes first for you: the images or the storyline?

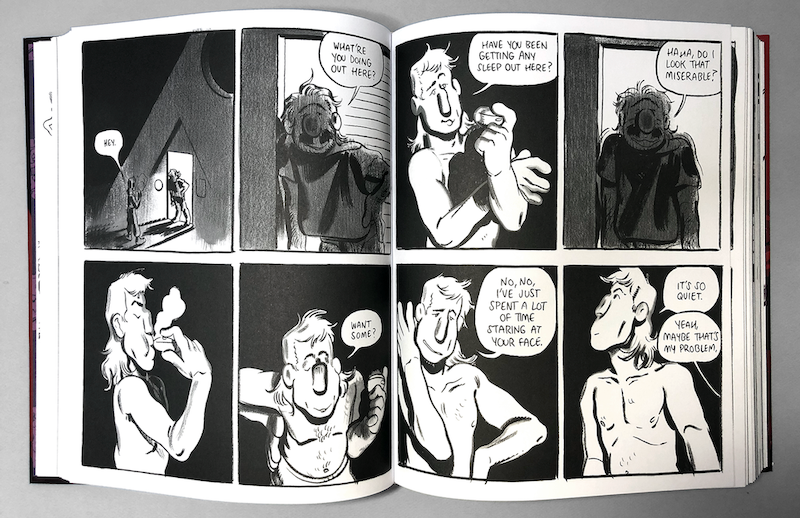

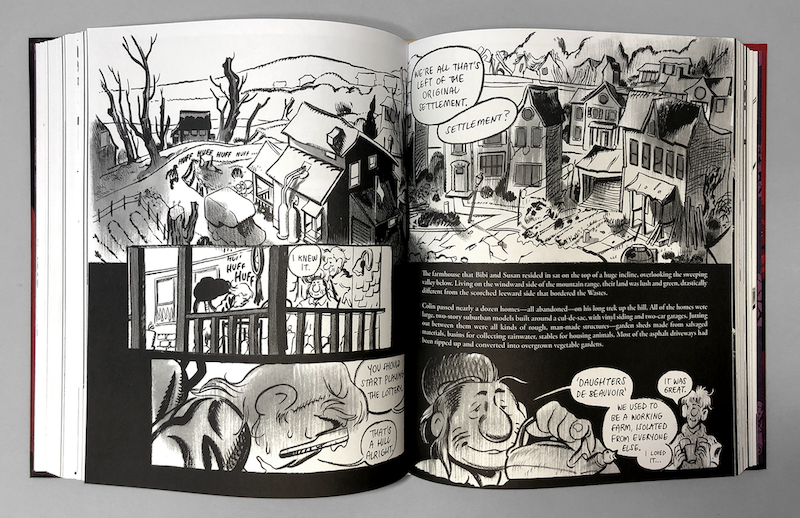

I feel like it’s the seed of a story first. With The Short While, for example, I pitched Nobrow a series of 120-page graphic novels that were in the same universe as Curveball but shorter, because I didn’t want to make a 400-page graphic novel again. That sounded awful. The plan was that it was going to be about a group of characters and each graphic novel was going to be about them at a different age, so certain things that happened in one book might be reflected in another book down the line.

And of course Nobrow was, like, “No, we’re not doing a sexy home invasion, that’s not us as a publisher. We’re very British.” At the time, I was also doing nonfiction essays online, which was how I was sort of paying the bills, for places like Lambda Literary, Topic, Medium, and Buzzfeed. And I think those two halves—these scraps I had from this failed graphic novel combined with this auto-bio prose— sort of fused together to create this science fiction genre based around characters over long periods of time written from this omniscient point of view.

I remember talking to you at a party a few years ago and you were super excited about the concept of home invasions in horror movies, particularly as it related to your book.

[laughs] My boyfriend Holden is such a horror movie buff in a way that I’m not. I’m just too much of a scaredy cat to really want to watch horror movies, so it’s been interesting talking to him about my book. He’s very much of the persuasion that it’s not a horror story. He’s like maybe it’s a thriller, but it’s not horror.

To me the point [of The Short While] was just to try to talk about this moment in my life, essentially. To try to talk about being anxious about the world we live in and how that manifests. With Curveball, yes, it’s science fiction, but I was never really that interested in the trappings of it, with all these tried and true tropes. And I think the same thing is true of horror: I’m interested in certain aesthetic things and certain narrative tricks, but I’m not necessarily there to make a tried and true version of that story.

How long did The Short While take you to complete?

I basically had the idea when I was on tour for Curveball, and started a Notes app version of the story in 2015. That fall I was sort of pitching it around and then finally got an offer in the summer of two thou—gosh, in the summer of 2018, I think. I was drawing it that whole time. I remember it took really long to find someone who wanted it.

And at that point you had basically finished the book, or at least an outline of it?

I had drawn a ton of it. When I was in college, there were always these conversations about essentially writing a pitch to a publisher and then they either like it and they buy it or you try another publisher. But there was never a conversation about how you almost at least have to draw the thing first and then find a publisher, which is my experience. No one has that luxury in graphic novels to just pitch an idea and then have that be purchased.

Unless you’re Adrian Tomine or Chris Ware—one of the top five?

Exactly. So the book was always being drawn sort of piecemeal as I was living my life. It wasn’t until 2018 when I had an offer and then I started to ink the spring of 2019. Then I got hurt in August 2019 and had to stop inking until January of 2020. I essentially inked from January 2020 up until June of 2021, and that was when it was like done, done.

So we’re looking at around five years, give or take?

Yeah.

Did getting hurt in the middle of creating The Short While change the trajectory of that project?

Absolutely. The strange thing is that the content of the book itself didn’t change all that much after my assault but rather the story, as it’s author, felt more visceral and true for myself. A goal of mine early on was to tell a story where a group of characters experience a traumatic event but that alone doesn’t define them. I often feel frustrated by stories, especially science fiction and horror stories, where characters become fixated on an Ultimate Evil, causing the breadth of their entire lives to narrow down to a pinpoint. What is Jamie Lee Curtis doing in the off hours when she’s not keeping one eye open for Michael Myers? Do Jedi even know who they are when they don’t have the Sith to occupy themselves?

Now having my own personal experience with trauma that often unexpectedly sends my heart racing, I feel good about that decision to frame my story in this way. That my characters have no other choice but to keep thriving, like a tree absorbing a wrought iron fence, and that their lives are more complex than what more traditional storytelling shapes would allow you to think possible in a story about trauma.

In a previous interview you talked about working on Curveball years before finding a publisher: “It had been on me slowly chipping away at this mountain I was climbing. There was a lot of comfort in that, steadily working on something that I didn’t know would ever see the light of day.” What is that comfort for you?

When students ask me about making something that long, I think there’s this idea that I’m actively working on it everyday. When the reality is that I’m treating it a little bit like a diary, where I’m using it as a space to funnel a lot of my life into, but it’s consistently there for me when I need it.

And it’s why both Curveball and The Short While are so large— my process with them is that I tell the story in a way that allows me to draw through them. I’m not executing a pre-planned map. I’m not writing a perfect story and then drawing that and then it’s done. But rather I sort of take it for a walk, where I’m walking through it and asking myself, What am I interested in right now when I’m working on this? What feels pressing in my life? What can I point to? What do I want to say? And then let the story be a space for that.

One of the reviews that I got for The Short While used the word “discursive,” which is a word I never think of. But I’m sure they thought “Oh, this is someone who’s taking a meandering path through their own book.” To me I think the joy is making a book like that because it feels like how life feels to me, where there’s no rush to get to the end because you can’t force that. And so instead of trying to make work that is very quick, that I’m trying to burn through or trying to have a strong deadline—I need to hit this soon before I get bored—I try to do the opposite: I know I’m going to get bored. How do I then treat it as a space that I won’t get bored in?

So doing things like formally changing up how the story reads at a certain part or bouncing back and forth between different characters or sort of treating everybody as equal within the book. Because that to me feels truthful and honest and feels like how I think the world should function.

How do you know when something so big is finished?

For me, especially with this last book, I had nothing else to say about these characters from this point in their lives. I felt like I’d reached the end of what they’re telling me—it wasn’t even what they’re telling the story, it’s more what versions of them I needed at that time.

So listening to the characters themselves?

Oh yeah. With Curveball, Melissa, my roommate at the time said “It feels like 30 versions of you talking in a room,” and The Short While is exactly that as well. It’s just a bunch of me’s discussing, essentially, the time in which I made the book. It was just thinking through the ways in which I’m moving through the world and how different parts of my life and different parts of me are sort of bouncing against each other. And eventually, I outgrow that version of myself. That’s kind of when the book feels done.

Because you were once a writer for The Steven Universe comic series, to what extent are you thinking about your books’ potential for adaptation?

I’m never thinking about it, truthfully. I think in a way this book release has made me more aware of how narrow that world has become because of market interests and because of comics moving pretty squarely in the world of entertainment, rather than art.

A couple of years ago, Holden and I were talking about this and he was like, “Jeremy, you are smart enough to know what a publisher would want, you could do that very easily. But the truth is, I don’t think you want it in that way.” And I agree with him now. To me the joy of making things is to be like, What can I make? What new and unexpected thing can I put out in the world? That process is really fun for me. And I think recognizing what does get produced at a higher Hollywood, Disney industrial complex kind of way—by the time that I would have to mush myself into being as small as possible to make that function, I don’t think I would be happy. I don’t know if I could bend myself enough and still enjoy what I make.

But Jeremy, don’t you like money?

[Laughs] I know. To me, I love what I do so intensely that I never want to hate it. Like it’s such a fear of mine that I wake up one day feeling miserable about making work, so I’m very protective about that space. I’m very protective of the joy. It’s not negotiable to me.

As an author and freelance artist who teaches at art schools, what does your financial pie chart look like in the last year?

My advance for The Short While was 20k—after agents fees, around 18.5k—but that contract was signed in 2018 so spread out over three years, that money alone is not enough to live off of. With teaching, I get around 5k a semester per class, sometimes a little more, sometimes a little less, depending on the institution, which is around $1,500 a month for the three months of the semester.

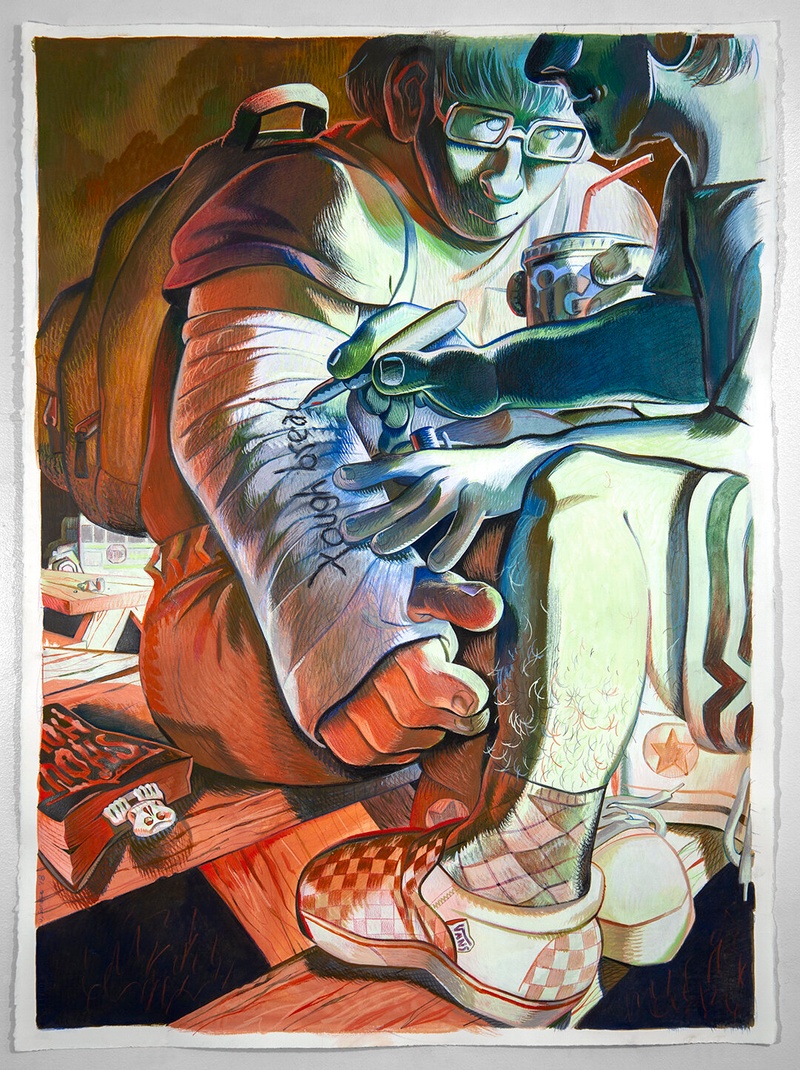

Editorial is sporadic—I’ve only done two editorial jobs in 2021, which in total came out to be just shy of 2k. At this point, my most consistent money comes from painting commissions which has been a very unexpected development in my life. I’ve done four this year, which in total is just shy of 4k. Ultimately, I’m looking to get better paying work outside of the arts in the new year. I would love to see what it’s like to make more than 30k a year.

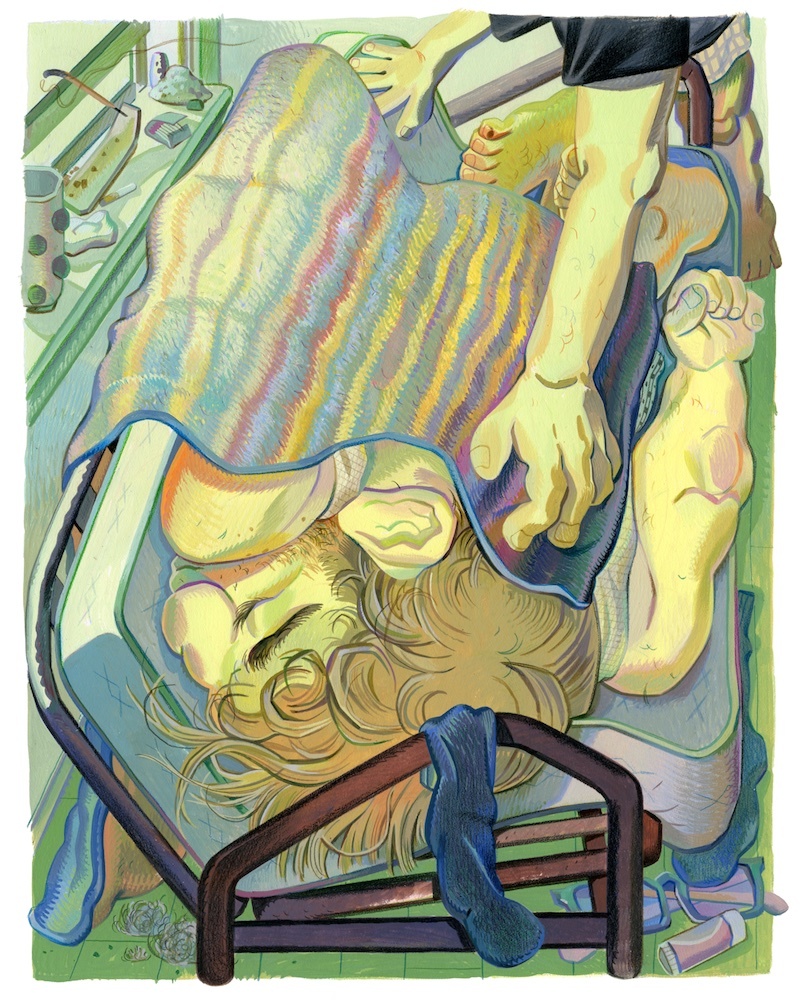

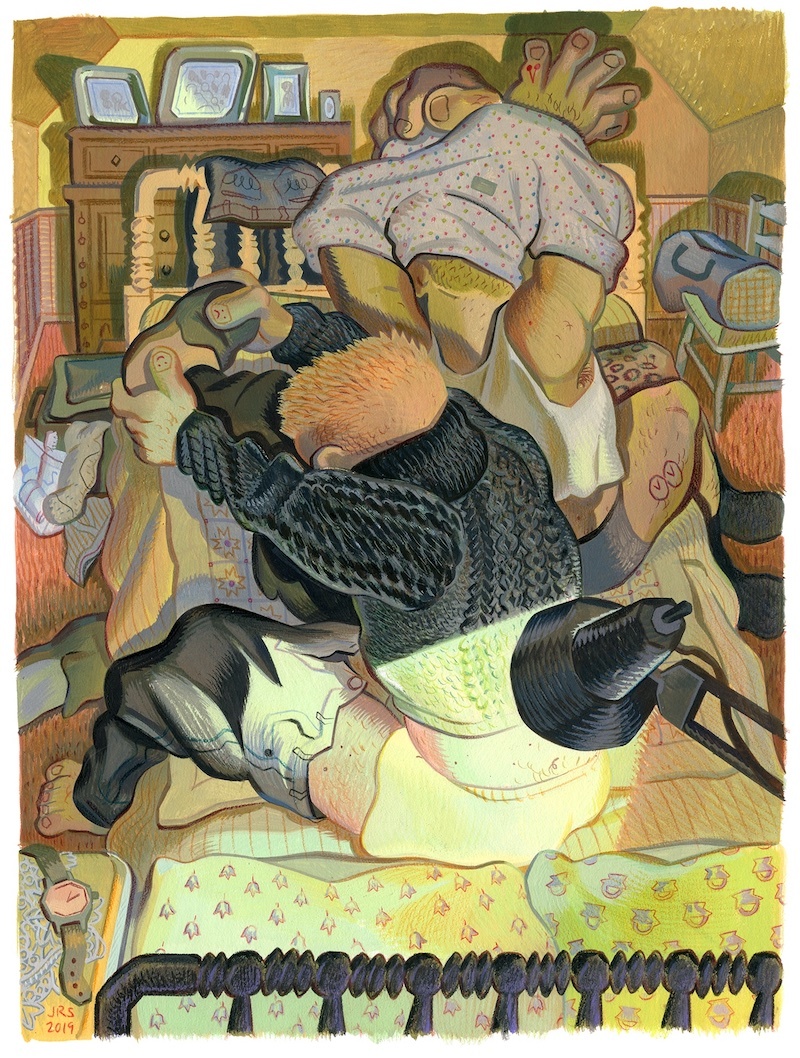

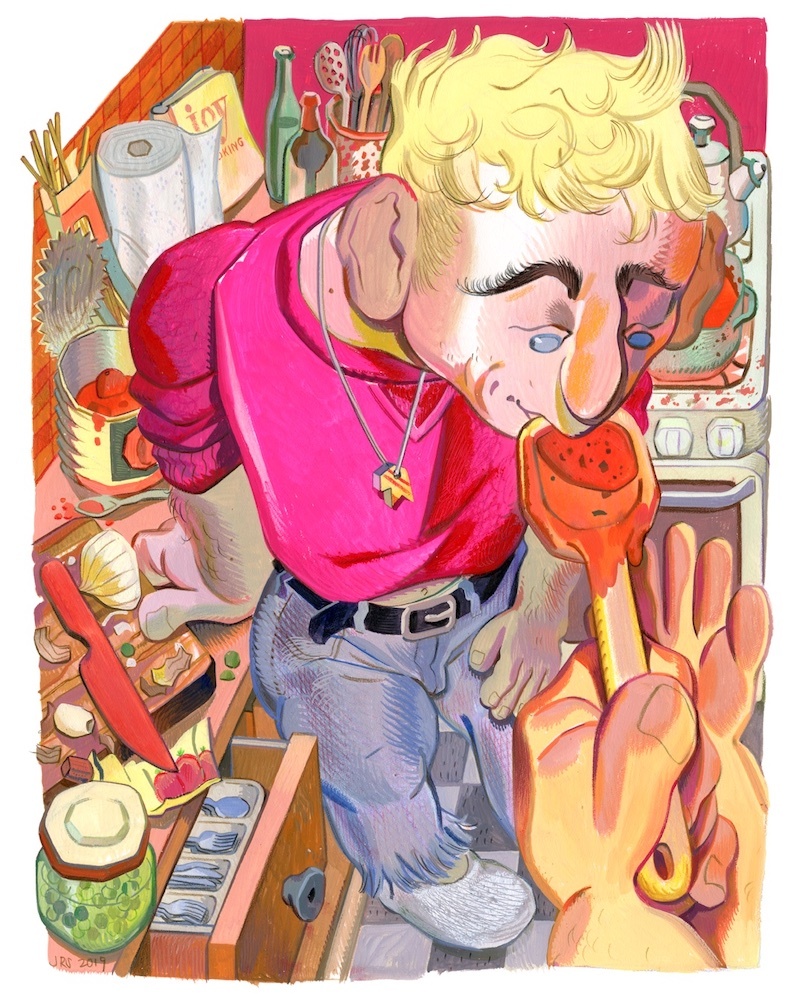

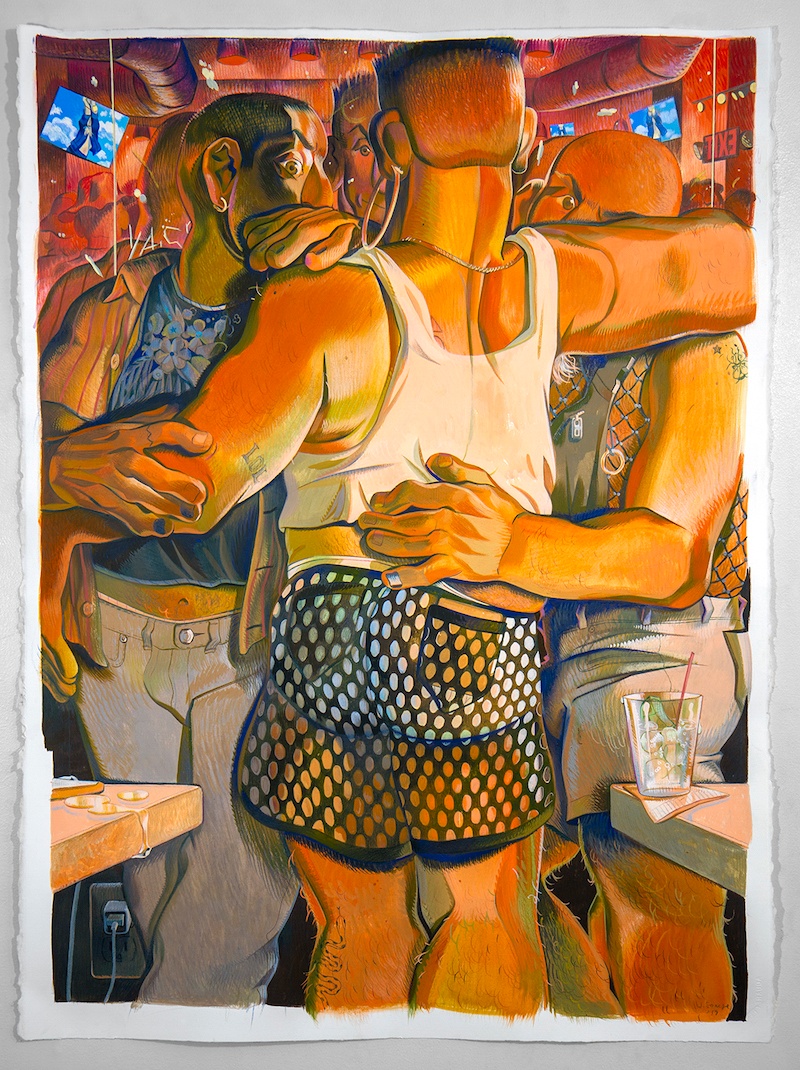

Your paintings often depict these snapshots of queer domesticity, tiny moments that feel hugely cinematic and fleshy and contain so much story within a single image. To what extent does that practice feel related to your graphic novels?

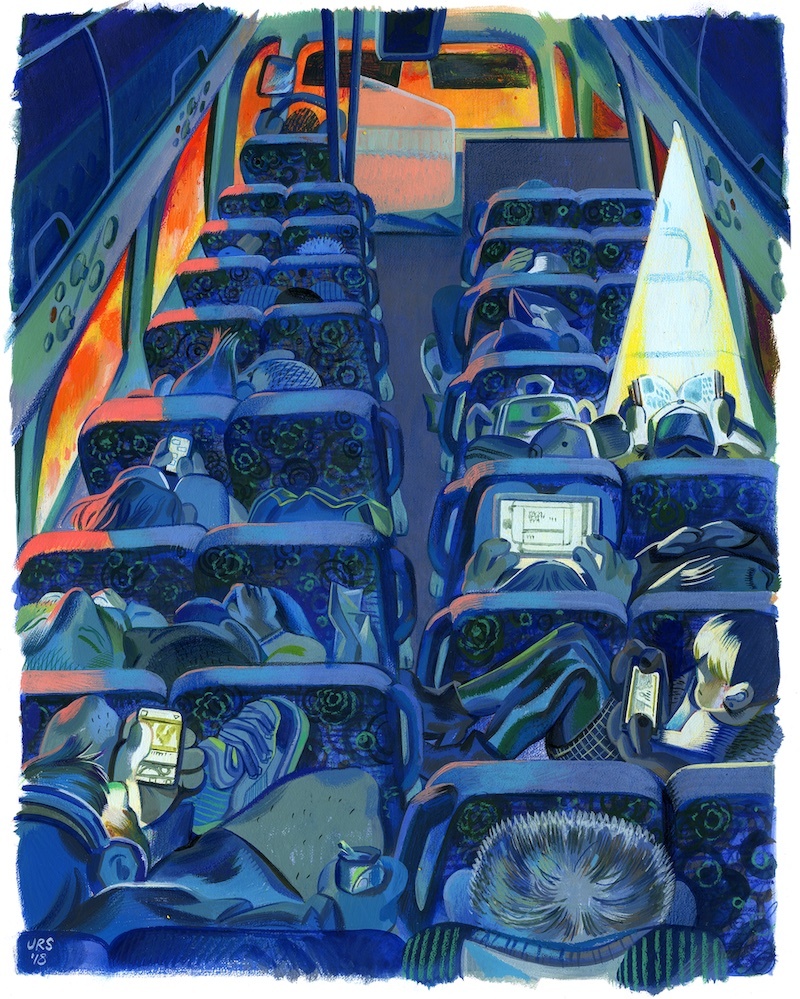

In the same way that my science fiction work is trying to talk about this time we’re living in, my paintings are trying to do the same thing: How do I show what it’s like to be alive in this moment? And how do I depict the wide range of people in my own life that I’m privileged enough to know?

What can I make? is maybe the root of a lot of it. What can I stretch this idea to be? What can I do with the freedom to be able to make a painting and then post it on Instagram? What can I really stretch this image making to include?

And sometimes that’s getting obsessive about detailing, about the objects in my own life or things I see on the internet or specific clothing. Some of that stuff does come from people I see on the streets or fashionable things that I don’t feel like I could wear but definitely want to depict.

The objects in the frame feel like plotlines or something— as animated and alive as the subjects.

Yes, and with everything, I feel like I’m using it as a diary. Even if they’re just ways for me to remember something, I think that’s exciting to me as a time capsule. I’m just trying to fit as much in so I don’t forget.

That reminds me of something you said earlier about taking these conventions in say horror or sci-fi and then skewering them a bit. And so the same with gay art, there’s this whole convention and history behind depicting gay bodies that your paintings feel in conversation with: what do those conventions look like on these particular bodies, via these weird comic forms?

For me, details feel like a thing that people often forget. But they just feel so telling about the lives we lead, in the world in which we live in, and the way in which we try to depict ourselves. With my students, I’m always like, Get specific. Find a specific tree on Google and draw that specific tree. I think that’s the thing that gets really lost in conversations about work, where profitable work just naturally has its edges smoothed down. And it’s something that I feel very aware that I’m not, probably as a detriment to my financial career as an artist. I just want someone to really want to go to bat for my work. And I think in a way making things more complicated is kind of a test, even if I’m not maybe aware of it in the process of making it. I’m just so aware of what is asked of me to be more profitable and I think I’m uncomfortable, maybe, with that profitability, so I try to push and challenge myself to be more specific and never let myself make a story or a piece that I feel is already in existence. Especially with the internet, I have moments where something I post does really well and it’s a dance: Do I just make that a bunch over and over and over again? Or do I challenge myself to not rest on my laurels? Part of that is the fun for me, of being a little uncomfortable.

Part of how you talk about your work—inviting all these different parts of yourself into a conversation with one another—feels like therapy in a way, but does “therapeutic” feel like an apt word to describe your process?

Oh, absolutely. It’s interesting though because it’s something I don’t really think about all that often. I’m not sitting around like, “Oh, this is therapeutic.” Or even feeling comfort each day.

The catharsis?

Yeah the catharsis is not happening very often. But I think maybe it’s coming from a place of knowing so many people who are not happy making work or who have had to position themselves in a place where it’s all business and the actual making is kind of moot. Or even knowing how many people I graduated with from college 11 years ago who don’t make work anymore, and that breaking my heart. I think I’m trying to stay focused on the making and how it feels to make something and focusing on that as a way of grounding it has been a solution to just a hard way of living a life. The goal always has to be on the work and what I’m feeling in the making of it because anything beyond that is just going to melt my brain. It’s just going to stress me out and it’s just going to ruin it. It’s just a quiet life, and I think trying to be okay with that is part of it.

It sounds like you’re being really intentional about playing the long game, rather than burning out.

I have a very strong memory of running track in middle school, which I was not very good at. I just remember there was something about running a race and you’re on the oval of the track and you get to the other side of the track and everybody is on the bandstand on the other side and it’s just you and your panting breath. There’s not even anyone around running, like by this point it’s pretty clear that you’re going to get third place and that’s fine.

I think that feeling, that memory, is so strong and it’s something I go back to all the time. There’s just a gap between the people who are interested in your work and you, and the process is not letting yourself be too desperate to get back to the other side of the track. You just kind of have to go deep and let that be comfortable.

Jeremy Sorose Recommends:

Tell Them Anything You Want: A Portrait of Maurice Sendak

The dress sight gag during Bernadette Peter’s opening number in Sunday In The Park With George

The Will To Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love by bell hooks

Listening to the Dublin Murder Squad books by Tana French as audiobooks to learn the slang (“Fair Play To Ya” and “Take a Legger” being a highlight for me.)

Weekly rituals: for me that’s dropping off my compostable at the community garden, feeding my sourdough starter as well as my kombucha scoby

- Name

- Jeremy Sorese

- Vocation

- cartoonist and artist

Some Things

Pagination