On letting your imagination roam free

Prelude

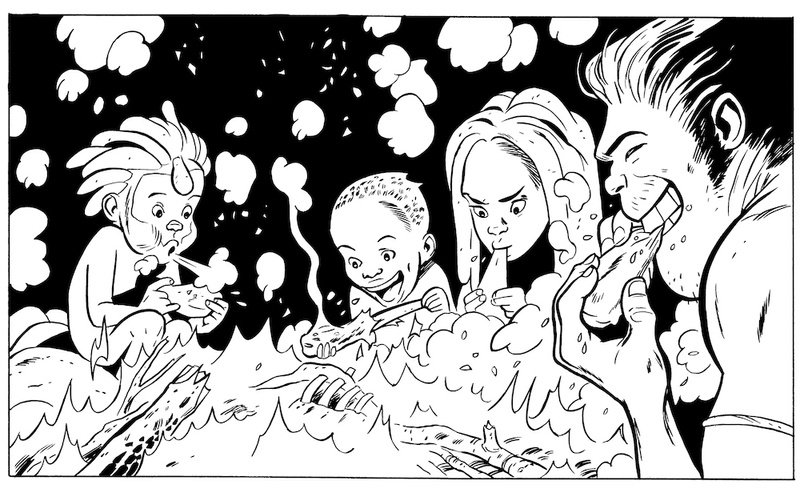

Jeff Smith is the New York Times Best-Selling author of the award-winning series, Bone, which is published in over 30 countries and is among Time Magazine’s “Ten Best Graphic Novels of All Time.” Bone was a pioneer in comics publishing for kids when it launched Scholastic’s graphic novel imprint, Graphix Books, in 2005. Smith’s other award-winning and acclaimed comics include Shazam! The Monster Society of Evil, RASL, Little Mouse Gets Ready!, Rose, and Bone: Tall Tales. Smith splits his time between Columbus and Key West with his wife and business partner, Vijaya Iyer. In 2021, he launched a Kickstarter campaign to publish Tuki: Fight For Fire and Tuki: Fight For Family, two graphic novels set during the dawn of humanity.

Conversation

On letting your imagination roam free

Cartoonist Jeff Smith on going your own way, the role luck plays in success, and the importance of staying connected to your inner child.

As told to J. Bennett, 3221 words.

Tags: Comics, Independence, Collaboration, Beginnings, Success.

How would you describe your artistic philosophy?

There’s usually a picture of something in my mind that’s the beginning of an idea. And for me, it’s usually comics. In fact, it’s always comics. But there may be one image that I’m aiming to bring everything toward. For example, with a book I did called RASL, I knew I wanted to have this fight with this guy who was very creepy looking. And I was writing kind of a noir, quasi-sci-fi book about parallel dimensions and things like that, so then I had to back up and figure out how to create a story that builds up to that and connects.

So that’s what I usually go for, even if it’s within a scene. Because I’m usually writing a story, there’s scenarios, and each piece gets broken down into smaller bits, but always at the heart of it is some image that I then back up and try to really build to.

You came up with the initial sketches for Bone when you were just five years old. Do you think that childlike sensibility carried through the series?

Oh yeah, I do think so. There’s something about wanting to do art, and especially wanting to do comic books, that means you do not relinquish your nine-year old self. I can still access that part of me—as I’m sure you can, too. Everybody really does. But there is a lot of artifice and weight that’s placed on us as we grow up and become adults. I think one of the reasons I enjoy making art is that ability to separate myself from those layers of societal responsibility and being able to find a place that’s very quiet and that is just for you to explore and use your imagination in exactly the same way you did when you were a kid.

In fact, I sometimes describe the process of making comics, whether I’m writing or doing the pencil or even inking, as a very Zen-like experience. Once that pencil or paintbrush hits the page, the world goes away. I am in that world. I’m creating a frozen moment of it—literally what I’m doing on the page—but I’m there and that moment is a living, breathing moment. That character that I’m drawing is moving and thinking about something, and I’m just trying to capture that. I’m trying to bring that out in pen and ink. And I’m gone. My wife Vijaya comes up and talks to me while I’m there. I look up and see her mouth moving before the sound kind of comes back in.

I feel like having access to your inner child is a requirement for any artist.

It is for me, and I would guess that it is for pretty much every single other artist. The whole point of art is to get back to that place where there’s no limits, where everything is possible. And even when you’re doing art where you’re trying to say something…well, for me it’s not so much that I’m trying to teach anybody anything or I’m trying to make someone learn something. It’s usually that I’m trying to figure something out. I’m trying to figure out how the world works and what’s happening to people when they have to make certain kinds of decisions—that kind of stuff. And I love being in that spot, because you can go anywhere from there.

What were your main objectives when you started Bone?

Most of all, I wanted to do a comic that I wanted to do—as opposed to comics that other people want you to do. And I wanted to do something long. I wanted to do something on an epic scale that hadn’t really been done in comics before. I mean, people had done graphic novels before, like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and Alan Moore’s Watchmen—those kind of books—but they were still novel size books. I wanted to do something like Lord Of The Rings, or the Iliad. And, of course, I chose a really silly, ridiculous story to do that with, but I was committed.

I wasn’t sure if I would make any money at it, but I was just going to do it, so I mapped it all out. I wanted to explore the world of fantasy. I’m interested in world building. And I wanted to see if with these kind of big-nose, big-foot characters, these traditional American cartoon characters like Bugs Bunny or Mickey Mouse, if you could tell a straight through-line epic—beginning, middle and end—horizontally, but then vertically build in depth, and do that with characterizations, stakes, and personalities.

And for me what was interesting is something that runs through all of my work: There’s something we can’t see. In RASL, it’s particle physics. In Bone, it’s this dream connection between every living being. Or in Tuki, my latest thing on Kickstarter—a book that takes place two million years ago—there’s a spiritual world of forces that they all believe in and might be real.

Did you work from an outline when you started Bone?

I did. I would call it a very loose outline because I’d sort of done a dry run of Bone as a daily strip in my college newspaper for a few years. So the story kind of bubbled up to me while I was doing that. But at first I didn’t really have a story in mind. I was doing these fish-out-of -water kind of comic strips, these three cartoon characters who come from a place that’s like us—the Western world—and go into this kind of fairytale forest world. But eventually a story bubbled up. A story had begun in my mind, and I was determined that I needed to find an ending before I committed to drawing anything. Because I knew that to have an epic story it had to be worth telling. So my outline had the ending, the middle, the beginning and a few tentpoles in between. And that was enough. I just got going.

Did you end up sticking to that outline?

Pretty much. I figured I knew the characters well enough that if I just got started on this road map, I could do everything I wanted as long as I went through one of these tent poles, where I knew a certain event had to happen or I knew a certain character would get introduced. Sometimes I got a little way off the path for a while, but then I would work my way back. And then 12 years later, I think I got rid of one or two of the last tent poles because I didn’t need them, and I got to the end. And it was pretty much the exact same ending I had written 12 years earlier.

What are some of the key things you learned about story?

Well, one was the horizontal line of beginning, middle and end, plus the vertical line of depth that I mentioned earlier. Depth is so important. I’ve done projects where I didn’t have that depth—I was just worried about having a story—and it was shallow. And it’s hard to force that depth, too. But when it shows up, suddenly I have a story that has mystery and heart and warmth. Even if it’s a cold sci-fi story like RASL, that mystery and heart and warmth keeps me involved—and I think the readers, too. It makes the pages and the action come alive.

You’ve been consistently independent and self-published for decades now. Why has that been important to you?

At the beginning, it was my hero, Walt Kelly, who did the comic strip Pogo. He died in 1973, but he continues to be one of my role models to this day. He owned the copyright of Pogo, and each daily strip was signed with a circled copyright—every single one of them. But when I took my comic strips in hand and went to visit syndicates, or sent in submissions, that was never allowed. But I wasn’t going to sell my copyright—that is unacceptable. So I learned from that process that if you want to own your own stuff, you’re on your own. They’re not going to work with you.

Around that same time when I was learning that heartbreaking truism, I went to a comic book shop for the first time as an adult and discovered this world of alternate comics and underground comics—and self-published comics. And I was like, “That’s it.” No more going to some gatekeeper with my hat in hand. You know, I wanted to draw comics from 1982 until ‘91 when I finally published. I was like, “I’m not waiting for somebody to give me permission anymore, and here’s a route to do it—self-publishing.” And I’ll be honest: I was as surprised as anybody that it worked.

I imagine it was difficult in the beginning.

I was just hoping I could sell enough to pay my bills and help with the household. I owned a little animation company that I sold to my partners, so I had a little nest egg which would hold me for a year, I figured—and Vijaya had a good job. I wrote up a business plan and said I’d go one year, but if this isn’t showing any reason to keep going, I would go back to animation, which is what I was doing before. She agreed, so that was it—I took off.

The first four issues were very dismal. But I started getting letters, and I started hearing from people like Neil Gaiman, saying, “You’re doing great.” And I was going to shows to try to promote the work. In those days, comic book shows were much smaller, so everybody was hanging out in the lounge of the hotel. Frank Miller would come up and slap me on the back and say, “You’re doing good, kid.” And he was the one who said, “There’s going to be some little pieces of wood with your name on them soon”—meaning some of the awards and stuff.

The sales hadn’t really gone up or anything, but Vijaya and I were like, “Well, that’s a reason to go a little bit longer. Let’s keep this up.” And thank goodness, Frank was right, because I started getting critical praise and awards, and then the sales just started going like crazy. So I knew I had to keep going. I was able to follow my imagination. And it was quite a ride. I had a wonderful trip doing Bone.

The success of Bone can be mostly attributed to the great story and characters that you built, but is there anything else—like the way you ran the business side, or pitfalls that you avoided—that helped that success?

Well, sure. Some of it is very much of its time. For example, in comics we now have a single distributor: Diamond Comics. However, there used to be 11 distributors when I started—some of them were national, some were regional, but there were 11 monthly catalogs. And there was a point where a lot of those distributors shut the door on independents. But if one distributor didn’t carry your book, a whole bunch of others might. That’s gone, and it’s never coming back.

Another thing was just the luck I had. For some reason, the comics that were really exploding were the ones that had gimmicky covers—you know, like hologram covers and foil logos and stuff like that. People were buying multiple number ones, and they were thinking they were going to be worth money. And I think as that started to backfire, people started to look for something that had a little more authenticity. And I think this part of my journey was just pure luck. I happened to be near the spotlight when people were looking for that authenticity, and here was this guy just doing a little black-and-white underground comic book out of his garage that people were really liking. So I think you never can tell what kind of luck is going to hit you, but of course when you see that opportunity, you’ve got to move quick and take advantage of it.

Today, there’s Kickstarter and there’s the internet—there’s web comics. And it looks to me like there’s something viable going on here, where it’s a perfect proving ground for a young cartoonist. You can put your stuff up there, and you can prove that people have interest and faith in you and your project. You’re skipping a step there—the gatekeepers or distributors—that I don’t think anybody is going to miss, to be honest. But that doesn’t mean they only want to go directly to readers. They want to be on the bookshelves of comic book stores and regular stores. So now we have to figure out how to get that book that was successful in Kickstarter onto comic book store shelves. Maybe it’ll still be through distributors. That’s fine. But it’s not a step one, step two, step three process like there used to be. That’s gone.

I also feel that the gathering of comics people at festivals and conventions is very important. It’s an important act of tribalism. Because you go there and the creators are there, the readers are there, the publishers are there—journalists, critics, everybody’s there. The retailers are there. Every retailer I know—and I’ve known a lot for 30 years—loves comics. These are not people running corporate bookstores or department stores. These are people that love comics, and they love finding new comics for their customers, and that gives me hope going forward. Hopefully soon, when this pandemic is over, we’ll all be able to get back together.

As you mentioned earlier, you’ve got a Kickstarter project going yourself right now. What do you make of the crowdsourcing aspect of it? Does it make you beholden to your fans in any way?

I do feel like part of this is making yourself very available. I’m going to be spending the next three months paying very close attention—figuring out if there are any problems and answering every question. But I’ve been around for a long time, and I’ve learned that it’s perfectly okay to ignore troublemakers—trolls and things like that. I haven’t really seen any on the Kickstarter yet.

But I want to meet my readers and I want to talk to them, and I’ve kind of famously been very approachable at conventions and bookstore signings and like to talk to people, because I want to know what they think. I need feedback. Because as a cartoonist—probably like most artists unless you’re in film or another collaborative forum—you’re by yourself. You’re just sitting in a room with a stereo. I mean, that’s it. It’s just all by yourself for long periods. I kind of joke with other cartoonists, but this lockdown probably was not as terrible for most of us. As cartoonists, we shelter in place every day for our whole lives.

You’re an established and popular artist, so Kickstarter might be easier for you than someone just starting out. What advice would you have for an unknown artist trying to start something new in this way?

I would do the same thing I did in pre-internet times. I always thought to myself that the interiors of your comic are your art, so get that as good as it can possibly be. Make sure that it’s not just something you would like but something you think would actually blow people’s minds or entertain. And then, from the [comic book] covers out to the world, your job is sort of like promotion. You’ve got to have a cover, a logo. It’s got to be eye catching. And beyond the physical covers, your job is to do what you can to bring your offspring into the world.

Another thing I did was I sent it to other cartoonists. I sent it to Will Eisner, and I had a couple of other people that I found a way to get in touch with. I physically had to write a letter back then and put it in the mail. It’d be a little easier now with email. And then I had Will Eisner give me a blurb. Pretty soon, I had three quotes from established cartoonists saying, “Hey, you’re doing good. This is a great comic,” and that helped. I didn’t sell a ton, but I obviously found out later that the people who knew who those cartoonists were—like Neil Gaiman—contacted me because they got it. They liked the comic.

So I would say in that sense it’s very similar to the landscape that I entered at the time, and something similar is happening. Once a few of us kind of got noticed, and got our heads above water if you will, more people were looked at, and it seems to me like a similar thing could be happening with Kickstarter now.

The good news is that the current generation is so fucking talented. They write comics about every conceivable genre. There’s such a diversity of characters and stories and art styles—and creators. When I got into comics, it was all old white guys. There were very few younger people, and very few women. The situation is 180 degrees from that right now in terms of race, age, gender, art style, comedy, painting—it’s wonderful. If you can’t find a comic that either is exactly for you or doesn’t blow your mind, then you’re just not even looking.

Jeff Smith Recommends:

In my studio I surround myself with some of these favorite artistic and pop culture pieces that I can dip into for inspiration/happiness at a moment’s notice:

Comics in general, but specifically these from when I first discovered them: Jack Kirby in his Marvel period with Stan Lee or his DC books—the bonkers but somehow genius Fourth World. Neal Adams and Denny O’Neil on Batman. Schulz’s Peanuts, Walt Kelly’s Pogo, Carl Barks’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge.

Films by directors that stand up to multiple viewing and continue to reveal storytelling secrets like Steven Spielberg, John Ford, Kurosawa, Chaplin, Keaton, and Miyazaki. Blu-rays with behind the scenes footage and commentary are the best when inking.

My walls are lined with books. Nonfiction for research and inspiration. Biographies of artists (from any discipline), Art Of books, art books, Pogo books and collections of classic comics.

I love listening to music, Sixties, Blues, R&B (l’m listening to Sam Cooke as I write this), Jazz, and movie soundtracks for when writing and working out a story.

The Beatles and The Marx Brothers are their own category. These guys are endless zen-like wells of fascination for me. Anything, biographies, collectibles, music, and every single film, good or bad!

- Name

- Jeff Smith

- Vocation

- Cartoonist

Some Things

Pagination