On giving people something to chew on

Prelude

Jen Monroe is an artist, chef, and music curator based in Brooklyn. Her exploratory food project, Bad Taste, was born from a desire to push the boundaries between food and art after years of cooking in restaurants and working in food media. Her work, most notably her series of immersive ten-course monochromatic dinners, has been publicized in The New York Times, Paper, Dazed, and Vogue. Other projects as Bad Taste have included an ongoing series of dinners in response to the honey bee health crisis, a large-scale jello installation at Knockdown Center, a futuristic dinner in response to the effects of climate change, and a series of experimental cotton candy pop-ups.

Conversation

On giving people something to chew on

Artist and chef Jen Monroe on what it means to work with food as your primary artistic medium, figuring out ways to freelance without losing your mind, and why you shouldn’t fear failure.

As told to René Kladzyk, 3200 words.

Tags: Food, Art, Process, Inspiration, Independence, Success, Failure.

You not only create adventurous meals and food art explorations, but you also DJ, you run Listen to This, and you art direct music videos and pop-up installations. I’m wondering if you see a through-line in your work, or even an underlying artistic imperative that propels everything?

Ultimately I think the connection is world-building. That for me has always been the imperative for looking at a dinner or a mixtape. There’s always the question, “What is the environment that I want to help somebody step into for an hour, or three hours?” For me it’s a process of approaching food from a visual perspective, as well as a textural perspective. When I plan a menu, it’s usually a texture or a feeling that comes before taste.

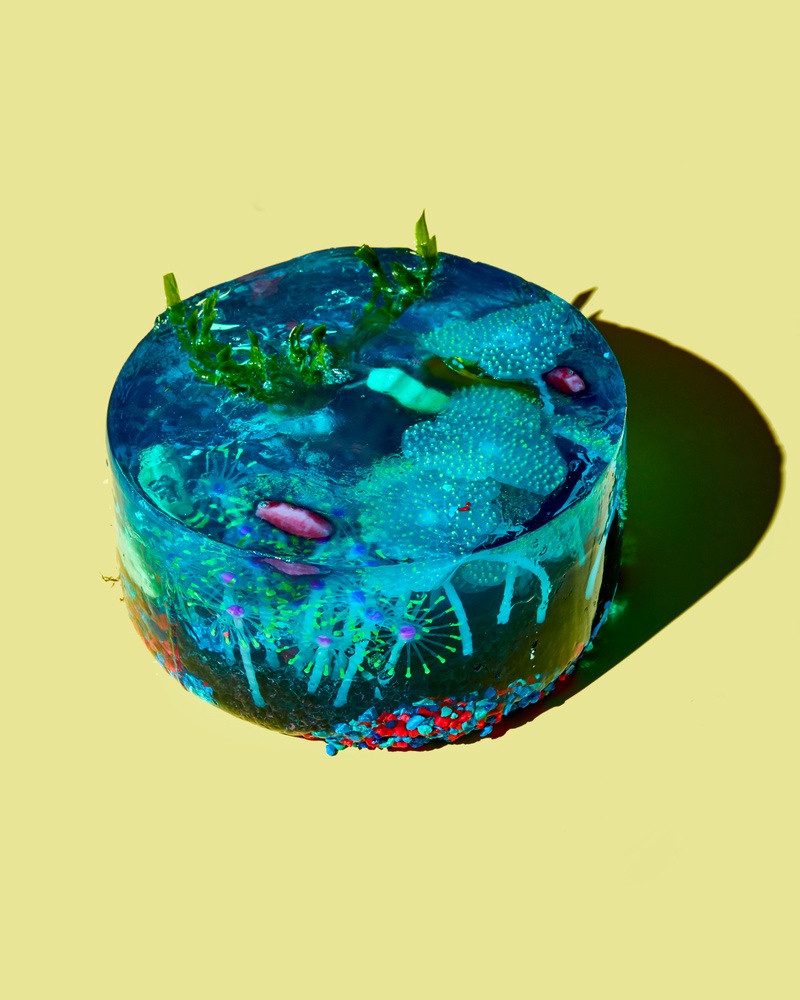

Photo: Henry Hargreaves

What’s most satisfying or compelling about attempts in world-building?

If I’m being cynical, the answer is that the world is a capitalist hellscape.

So escapism?

Yeah. All I’ve wanted to do is make these autonomous environment bubbles that we can inhabit. But I think nostalgia has everything to do with it, too. People ask me about what ethnic influences I cook with, and the answer is that I kind of don’t. I grew up around a lot of Japanese influences because my parents were both East Asian studies nerds, but we never had our own cultural narrative growing up, so as a result I’ve always felt like I was trying to invent or world-build my own. I think often that ends up feeling futuristic or sci-fi.

I was thinking about your honeybee meal though, and how that doesn’t feel even remotely escapist. It does feel like a very clear attempt at world-building, but one that’s grounded in the realities of our world and what role you can play in subtly re-molding it.

That’s a huge part of what makes food attractive to me, too. It can be an explicitly didactic or political tool while still engaging all of the pleasure sensors of your brain. Working on the honey bee project, where there is very clearly a political and environmentalist narrative, you can sneak the learning in so that people show up for dinner, and accidentally leave having ingested a little bit more than they signed up for. Which is always the goal.

Literally and figuratively make them really chew on it.

Yeah, surprise!

What initially drew you to working with food?

I started learning to cook when I was a sophomore in college, having my own kitchen for the first time and learning to feed myself. I was pretty bored and unhappy at school at the time. I found satisfaction in making a functional object where there was none, in the course of an hour, or two hours. Having it be meant to be consumed, but still ultimately feeling like you’ve created an art object with your two hands was a really shocking and radical feeling to me. I kept making these elaborate things in my kitchen and I would feed them to my boyfriend, and I’d want to shake him and be like, “Do you see what I did? Look what I made! This is crazy! This didn’t exist a couple hours ago. And now there’s this thing we’re going to eat together. This is wild.”

Photo: Corey Olsen

Photo: Corey Olsen

From there I went further down the rabbit hole, trying to find a place in the food world. I wrote a food blog, and cooked in restaurants for a little while. I worked in a supper club. There was a long stretch where I felt like I was throwing things against the wall constantly. I kind of blindly fumbled around for a couple of years, and eventually landed in wine, which had never really been a passion but I came to love it. More importantly, it was an incubator job to have while I slowly figured out how to get this food project off the ground. In 2014 my sister and I started hosting monochromatic dinner parties in our apartment. I had some cooking background up to that point but I knew that I didn’t want to be a chef in any kind of conventional sense.

So that dinner series was the first?

Yes, but they weren’t public-facing. They were for six people in our apartment for fun, very half-baked. That was the first thing I had done in years that scratched the itch. I had gotten a little bit of a taste for it while participating in a supper club and…

So many food puns!

It’s true. I don’t even notice them anymore. So when my sister and I started doing this thing it was definitely a fun but undirected kind of thing. And then Mark at the Schoolhouse had said that he wanted to start doing some kind of food programming, so we started doing a series of monochromatic dinners there for 20 people. For me, that was the beginning of the bug, in terms of being able to basically art direct a meal. It was really fun and a very steep learning curve.

Food is an interesting canvas for creative work, because it’s so essential. It’s fundamental to the human experience. And it’s got such a high utility function. Can you talk a little bit about how you see food both inside and outside of “art?” Or if you find yourself having to navigate that boundary much?

I think any chef who tries to tell you, “My relationship with food is only beautiful and poetic and lofty,” is either lying or a gajillionaire and being waited on hand and foot. Especially as one who works with food in my livelihood, it is physical labor. It is often backbreaking, finger-bleeding, exhausted, underslept, over-caffeinated, haven’t-had-a-vegetable-in-a-couple-days kind of labor. And that’s just real. That’s part of the hustle.

But on the flip side of that is exactly what you said, that food is an essential resource and it’s one that I happen to have really privileged access to. So, with that comes a lot of hand-wringing. Is it kind of evil to treat it as an artistic medium? It effectively feels like standing on top of a pedestal and saying, “Ha ha ha, I have access to so much that I can afford to turn these bananas into a Christmas tree full of banana dolphins.” It’s deeply privileged, and it’s something that I’ve run into over and over again.

Ultimately where I keep landing is that all chefs are artists, and while I always want to be mindful of food access and respect and waste, I have to be ok with thinking about the radical ways in which we could relate to food in a better world. Or a worse world, which is what the environmentalist dinners have ultimately been about: how can we continue to invent pleasure for ourselves in a world of scarcity, and what can envisioning that future do to change our current relationship to food, or to the world?

Photo: Corey Olsen

Within the past year you shifted to being fully freelance. Can you talk about how that transition has been? How do you create boundaries between work and life? What do you struggle with the most?

The hardest part is time management. I work really well under a tight deadline, and when I have to be the one in charge of time management for longer-term projects, I have a hard time sitting down and being diligent. Also, the news cycle that we have been living in for the past three years has been so all-consuming that it’s easy to sit down and say, “I’m just going to read the news before I get down to work,” and then four hours later you’ve gone down a Wikipedia hellhole spiral. You don’t remember what’s going on anymore.

I’m sure anyone who’s looked up freelancer 101 listicles knows this but, you have to turn it off, otherwise you’ll keep emailing all night long. And then I’ll be lying in bed and remember, “Oh, I actually just have to do one more thing.” Having clean work/life hygiene is hard but also important. Especially when you’re a freelancer who’s “doing what you love,” those things start to get murky quickly. Know when to turn it off. Routine is also really important. I’ve been doing this full-time for about nine months and am only now starting to have good infrastructure about going to bed at a decent hour, and waking up at a decent hour.

Do you have any freelance hacks?

I don’t know if this is a great hack, but I have a dog, and he forces me to go for a walk first thing in the morning. And that, especially recently, has turned into a really beloved ritual.

Dog hack.

Dog hack! A dog will force you to leave the house several times a day, even when you are in a work spiral. So I’ve been in a really good ritual recently where I will wake up, take the dog out, get a tiny cup of bad bodega coffee, which is my joy in the morning. And then we’ll go over to the basketball court nearby and run around together. That’s been a beautiful way to start the day. Then I can come home and feel like my brain is awake, and I can sit down and jump in.

Also, reward systems. I know that’s also a really level-one piece of advice, but have treats for yourself. It’s important. Right now it’s orange season, so I have some really tasty oranges that I have been periodically rewarding myself with. But treats can take many forms. They can be playing a game, or having a reading break, or a favorite snack, or playing with your dog. That stuff all helps.

Can you recall any artistic advice you’ve been given that’s been useful? Or, what advice would you give to your younger self, or to someone perhaps setting out on a path that’s similar in some way?

What does come to mind is how important it is to have somebody close to you who is honest with you. Someone who gives you honest, blunt feedback, whose opinions you trust and whose judgment you trust to tell you, “Hey, I think this thing is a waste of your time,” or, “Hey, this thing was really great. But these parts need to be tightened up.”

Photo: Jen Monroe

We’re lucky that we run around in an artistic community where everyone cheerleads everyone. But ultimately that sometimes means that no one is going to tell you if your work is bad, or be a smart sounding board. I’ve been really lucky to have people, you being one of them, my sister being one of them, who will say, “Nope! Try again.” And my partner is also direct in feedback when he has any. If he’s unmoved by something he’s not going to lavish a bunch of flowery praise on me. And that’s important. So that would be the big one—keep people who you admire close to you.

Can we talk a little bit about how you define success, or understand it? What does success mean to you? Or what would you like it to mean to you?

It’s funny because a lot of the things that have happened to me more recently are things that I was so desperate for five years ago and used to think, “If I could just do this thing, or if this thing could only happen, then I would be successful. Then I would be happy. And then I would feel like I’ve made it. Then I could relax.” And now being on the other side of some of those things, I don’t really feel all that different. I still feel like, “When does this get easy?” Or, “When does this stop feeling precarious or scary or uncertain?” So I guess the takeaway for me has been, I’m never going to feel successful. Maybe other people wake up and go, “I’m a successful person. Off to work today!” But I don’t know if that’s ever going to happen to me, and I’ve had to make peace with that.

I would like success to feel like you have given rise to a useful conversation. And I guess that’s a broad desire for a reason. It could mean a lot of different things. But I think the reason people have children is because they want to be remembered after they die. And I guess in my mind, success is maybe a little bit less narcissistic than that, but I would like to have contributed in a productive way to a narrative that will continue after I’m dead. I don’t know if one can ever really know if that’s the case. But one can hope.

I think you can know that your ideas, your creative output has an effect. You’ll never be able to trace it in a finite way, because it’ll keep moving and changing—that’s the way ideas work. But I like that as being the definition of success, just contributing something to the ether. Something positive.

It’s easy to contribute something bad. Just to muddy the waters up a little. Anyone can do that. And especially with making food work that is more political or environmentalist in message—I can’t realistically hope that someone is going to come to this dinner and then the next day sign into legislation a really meaningful act of law that’s going to save the world. But I can hope for smaller nudges and pushes along the way.

It’s corny, but it’s the butterfly effect. You never know what’s going to land where and who your work is going to end up in front of and what it’s going to make them feel, what it’s going to make them do.

I don’t know if this is an answerable question, I just wrote it because it felt good to me. But when do you feel the most free?

That’s a great question. I said this to my boyfriend a while back: I realized that the moments when I am several days deep into a crazy food project and I’ve been doing back-to-back 16 hour prep days, I’m underslept, over-caffeinated, and I haven’t thought about whether I look particularly cute in a while, I’m wearing functional clothes and I feel like my body is just a tool, I’m a machine that’s working effectively, those are the moments when I feel the most free. When I can be just a brain and just a body. And I realized that a big part of what feels so good about that is that it’s the only time in my life when I’m not thinking about what I look like. It feels amazing.

I told my boyfriend, “That is the most freeing and amazing feeling, to not have to at all be aware of what I look like.” And he kind of laughed and said, partially jokingly but partially seriously, “Yeah, that’s what it feels like to be a man all the time.” Must be nice!

Photo: Jen Monroe

Is there any advice you’d like to share?

I think this applies largely to working with food in unconventional ways, but I’m sure it can be applied to lots of other creative endeavors as well. Don’t be afraid of failure, and don’t be afraid to make work that you’re maybe not going to be super proud of in five or ten years down the road. Don’t be afraid of a steep learning curve, because they’re easily the most rewarding ones.

Can you tell me about a rewarding failure?

This is perhaps self important, but I wouldn’t ever write off anything I’ve done as a complete failure. There have been mistakes everywhere along the way. I look back at a lot of early projects and I don’t feel particularly proud of them. I have done some things as an employer that I’m not proud of, which is something that for me has really turned into a huge point of growth—learning how to be a good employer. How to delegate, and how to create a positive working experience for the people who are working under you.

Obviously that is ultimately what every mistake is in service to, growth. I think food can feel particularly risky, because it’s a markedly different experience from looking at a painting you don’t like and then walking away from it. Food is invasive, personal, sensitive, and can be scary. If you prepare something that someone doesn’t like, all sorts of painful and uncomfortable scenarios could result. Treat it with respect. Don’t knowingly walk into failure just to learn, because it is a sacred substance. But based on my experience, people are more willing than you might necessarily think to find pleasure in strange places. And the stakes are probably not as high as you believe them to be in your head. There is always something to be learned.

Related reading: TCI’s Focus on running a business

Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk

Jen Monroe Recommends:

-

The Once and Future World by J.B. Mackinnon — the most empathy-inspiring piece of nature writing that I’ve ever read. A really ideal blend of poetic and technical, and will change the way you think about your relationship to the natural world, even if you’re already a committed environmentalist. Effectively reads as a devastating love letter to that which we’ve lost.

-

Stardew Valley — a farm simulation game that feels like what might happen if Miyazaki remade FarmVille. Pastoral, extremely relaxing, great soundtrack, and guaranteed to light up all of your brain’s reward centers. Avoid this if you’re on a deadline, have an addictive personality, or are generally bad at time management.

-

Nori butter — mash up some room temperature butter (fancy or cultured butter if you want) with a ton of crumbled seasoned nori and flaky salt. Magical on toast, rice, eggs, fish, whatever.

-

The Instagram account @chinese_plating, which is my favorite Instagram account. Image scans of extravagant vintage Chinese foodscapes, taken from the National Archives in Beijing. Extremely inspiring.

-

Early Western choral music — largely sacred and acapella. The best stuff appeals regardless of your religious affiliation and is ideal wintertime music (or quarantine music!). Some of my favorite composers are John Dunstable, Hildegard von Bingen, Pérotin, and Thomas Tallis, but if you don’t feel like digging around I’ve made a couple mixes of my favorite ~monastic moments~ here.

- Name

- Jen Monroe

- Vocation

- Artist, chef, music curator

Some Things

Pagination