On being the inspiration that others might need

Prelude

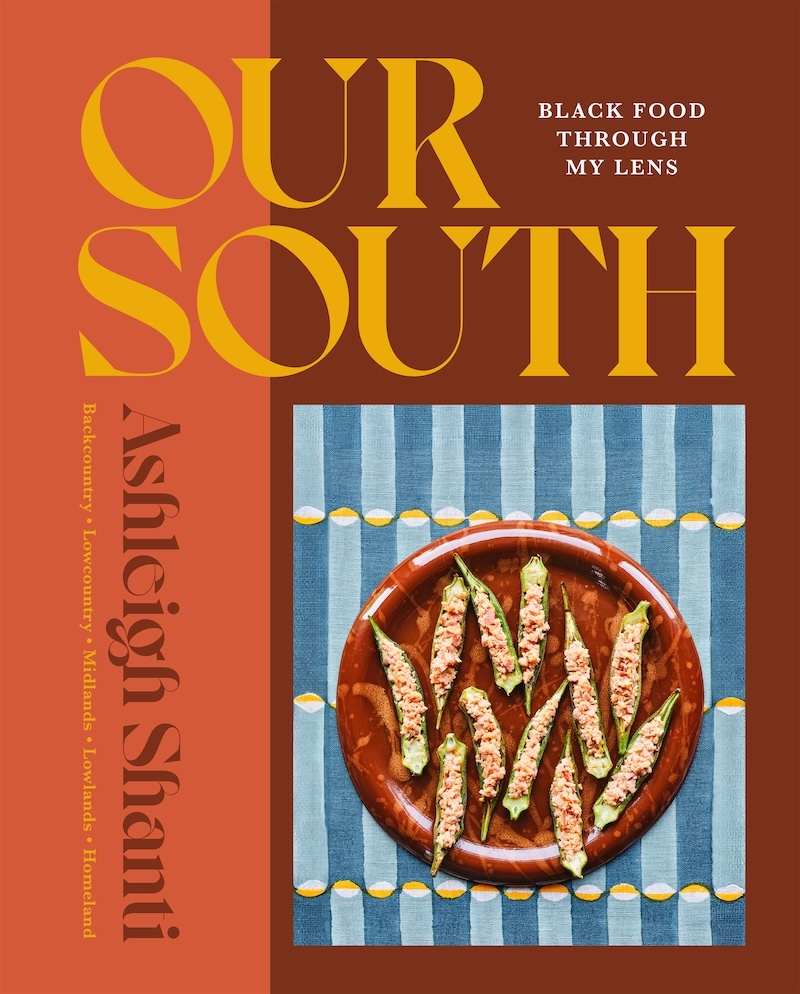

Ashleigh Shanti is the author of Our South: Black Food Through My Lens and Chef-Owner of Good Hot Fish in Asheville, NC. Born in St. Mary’s, GA and raised in Virginia Beach, VA, Ashleigh’s heritage has roots across the Southeast. She graduated from culinary school at Baltimore International College in 2013 and went on to stage at Minibar in Washington, D.C., and act as culinary assistant for Vivian Howard before becoming Chef de Cuisine at John Fleer’s Benne on Eagle in Asheville. She was named an Eater Young Gun in 2019 and was a finalist for the James Beard “Rising Star Chef of the Year” award in 2020. She was also a top five “cheftestant” on season 19 of Bravo’s Top Chef and was the winner of Restaurant Wars.

Conversation

On being the inspiration that others might need

Chef Ashleigh Shanti discusses how every maker of things inspires her, the importance of community collaboration, and what it's like to process her successes.

As told to Eva Recinos, 2564 words.

Tags: Food, Collaboration, Inspiration, Success.

You begin your cookbook, Our South: Black Food Through My Lens, by giving the reader a clear sense of your focus. You write that the cookbook is not going to be a Southern cookbook, or a chef cookbook. It’s more about challenging the belief that Black cuisine is monochromatic. Did you always know that this would be the lens for the book?

When I thought about why I wanted to embark upon this very special yet very challenging thing that I’ve never done before, one of the things that I kept coming back to was that I knew that there were recipes that were very familiar to me and very special to the regions that I felt like made me who I am as a chef that needed to be highlighted, documented, talked about. And one of the moments that I kept going back to was me being a young chef and having a really hard time finding this lens. And I just know that having that information and having those food ways [and] their history talked about on such a platform—having that readily available for me, I think, would’ve been very transformative. So, no, I didn’t know initially that this is how it was all going to play out.

I appreciate the way that you take us through your early childhood. You describe yourself as a precocious only child in Coastal Virginia, and how that was really important as one of your earliest food experiences. And then you also talk about your grandparents, their relationships to food and the land, and the visits that you made to family members throughout the South. What was it like to revisit these memories?

Revisiting the memories of my childhood was a really large part of writing this. And doing that was very nostalgic. I learned a lot about my family—some things that I didn’t know. It helped me to see the power of food. It really showed me how powerful food was in my family because, I mean, I even was finding skeletons in closets. And ones that I couldn’t believe were right in front of me growing up, all along. Those moments where we allowed the kitchen to be the gathering place, those integral moments where food was at the center—that just showed me how food truly is the great unifier. So, yes, it was a very special and emotional time diving back in that way.

You give us this great visual of your journey, going to Hampton University to study business marketing, but spending your time watching Food Network and cooking. You’d later go on to be a finalist in Top Chef. How have TV and pop culture been important in your journey?

For my family— my parents—me wanting to be a chef was a really hard sell. And for me, knowing that this is something that I wanted to do, I felt that I needed proof that I could do it. I wouldn’t call Virginia Beach a food city. I didn’t live in New York City, where you know who’s cooking the food in the kitchen. So when I was actually looking for tangible examples, it was easy to turn to places like Food Network and see someone like Rachael Ray or Bobby Flay and find inspiration in that. And also, being a latchkey kid, my parents worked quite a bit growing up, so I wasn’t supposed to be, but I did watch a lot of Food Network when they were at work… That was an introduction to ingredients that I didn’t have readily available and I wasn’t accustomed to. Things like Food Network had a pretty big impact on my formative years, and just falling in love with food.

Was it surreal, then, to be on Top Chef later?

Yes. Definitely, I feel like for the first time, I was able to understand what that phrase “out-of-body experience” meant. It was really important for me at that time to ground myself, and just remember that I had worked really hard to get there, but also that I was so grateful to be in that space with such amazing talent. Yeah, it was a pretty wild experience.

One thing that you’re really transparent about is how the food you grew up with, you didn’t really see as the food that you “should be” making as a chef. You write that you fantasized about going to restaurants that you read about in magazines like Food & Wine and that you felt like earning the respect of your peers in the kitchen meant cooking the food that you were seeing in these magazines. Why was it important to include this internal struggle?

It was important to include because there was a moment—this intersection in my career—where I just stopped caring what people thought. I just turned away from what I felt was this box that I was put in as a Black chef. In doing that, I readily turned to the food that was most familiar to me. And I was in a position where I was able to put that food in the same restaurants that I would’ve never expected to [see it] before. And the response was very warm… It was a really defining moment for me as a chef.

You mentioned that sometimes you felt like leaving the industry entirely. One thing that came to mind for me was just this, I think, push and pull that sometimes creative folks have—it’s like the industry itself as an institution can really get you down, but it’s not always necessarily about the craft. What fueled you to keep going?

I mean, it’s that thing you said: It’s the institution, I think, that can really grind my gears—this French hierarchy that doesn’t have the same warm, fuzzy feelings that I grew up with. And for me, people talk about hating their jobs often—and that’s not something I’ve ever experienced because I’ll never stop loving food. As long as my job relates to food, I’m always going to love it, and that’s always the thing that continues to pull me back in. So, I mean, I think it’s that—and just the respect of the humble Southern ingredient, and the makers that work so hard to get these beautiful things on our tables. Those are the things that allow me to continue to have that drive, even when the industry itself doesn’t always feel so good.

In 2020, you started to collaborate with other chef friends, putting on pop-up events, and then you were able to open your own restaurant, Good Hot Fish, in 2024. What were your priorities when you were starting your own space?

I was so focused on finding a creative space. I knew that, at the time, that creative space was owning my own restaurant and finally feeling like I have ownership of my own stories. And having that autonomy that I never really felt like I had as a chef—and being able to travel and cook with chefs that I really admire.

My biggest thing as a Black chef, as a woman that’s only worked for white people [is] I never felt like I had a seat at the table. And while I’ve put in so much sweat equity, I’d never felt like I learned the guts of how to run a restaurant. I helped so many people open their own restaurants, but I still just felt like I didn’t get it.

And that was the one thing that was really special about that time—I had friends that would sit me down and we would just go over their P&L statements for hours. And they would go over food and labor costs with me. That was something that I really cherished. Beyond that, of course, it was [about] having that platform where I could cook food without any real boundaries, and get some honest immediate feedback about it as well.

You shared that you realized, later in your career, that you weren’t the first person in your family who had multiple side hustles—that you were part of this long lineage of women who were also using their talent in the kitchen. What’s your advice, or what are some insights, for folks in creative careers that are maybe feeling unsure about this feeling of patching together side hustles? Or, maybe, folks who aren’t feeling ready for the leap, but they have something in mind that they want to pursue?

A lot of my drive is driven by just my personality. I don’t know if this is advice, but just in describing my personality and where that drive comes from, it is because of—even your question, what advice for other creators, because there isn’t a lot of advice out there. People often feel like there’s a glass ceiling and they can’t [do it] because there aren’t a lot of examples and they don’t see a lot of people like them doing it. And that is part of what drives me and why I push myself.

So I don’t even know if that is advice necessarily, but it is something to reflect on as a creative, especially Black and Brown creatives. Sometimes what keeps me in the game is that there’s going to be a lot of people, I would hope, that look like me and can find a reflection of themselves and find hope in that. It’s easy for me to note how much fulfillment I find in my career as well. And of course, there are things about what I do that can feel thankless, but I’ve been able to find such reward in what I do. So I think just focusing on what that reward and fulfillment is for you, and going after that is probably the best bit of advice I can give. Because it’s going to be really hard, so sometimes you really do just have to stare at the finish line.

Yeah, definitely. You’ve also mentioned that, in Asheville, you’re really surrounded by a lot of writers, and makers, and artists, and how you feel really grateful for that community. I’m curious: Is community and collaboration something that also feeds your drive at this point in your career?

Yes, and part of my gratitude in living here is that there’s just so much creativity around me, and that also fuels me. I talk about that in the book—we have so many makers around us, even just from the folks that grow our iceberg lettuce for our wedge salad to the trout farmers. And the folks that mill our cornmeal 15 miles down the road. That inspires me. And when I have a really special product like that in my hand, I want to make sure that I do it its due diligence. So, I mean, even down to the ingredient and just knowing that there’s a restaurant a couple blocks away that is doing some really cool things too. There’s a really incredible chef community here that’s super tight-knit, and that certainly helps when times get tough.

I would imagine you keep very busy, but I was curious if there are any non-cooking, non-food avenues of inspiration that you find?

Yes, but it’s funny because it all ends up tying back to food. I really enjoy nature and specifically foraging, fishing. Those are things I really enjoy. And of course, I usually do something with my harvest. But, yeah, I’m starting to get into more design stuff. My wife and I just bought a house not too long ago, so that’s been a fun and very, very new undertaking. So maybe a new interest, we’ll see if it sticks.

That’s exciting, congratulations!

Thanks.

In your cookbook, there’s such a visual lushness both in the photography that you include, but also just in your writing and the way that you’re setting these scenes from your childhood to present time. Why was this an important part of your process?

So, I mean, obviously, I’m a new writer, so I think I was doing a lot of what just comes naturally to me. I talked about just going back and revisiting a lot of those places. I did that physically as well. And even my proposal was written in my childhood home—a lot of times, I was just sitting in my backyard, the first place I ever foraged. And so maybe I was cheating a little, but that made it really easy to put all of these descriptors around these places, because I was in it. And also, the memories are so vivid. I can often close my eyes and just be in them again. And of course, like you said, the photography—I was able to go back to all of these places and just instantly feel like a kid again, and [access] a lot of those memories as an adolescent just learning what food meant to me.

What are some recent or significant interactions that you’ve had with other folks who have resonated with your story?

One thing I will never forget is this little sweet girl named Marley, who I think, at the time, was in the fourth grade. It was when I was a chef at Benne on Eagle, and it was during Black History Month. She did her Black History Month project on me and did her presentation in front of the class. Her mom took pictures, and at the time, I think I wore a bandana almost every day to work. She wore a bandana and had a little chef shirt on. It was really cool. And I still have the pictures from that.

We have another little regular that comes into Good Hot Fish all the time and wrote us this letter that inspired some merchandise. And it’s just things like that that really keep me going and make me smile… Like I said, some days can feel a little thankless, and those are things I hold onto.

Ashleigh Shanti recommends:

All About Love by Bell Hooks. This book has taught me a lot about love and its many forms. Profound but straight to the point, I find myself referring to this book through just about every phase of life.

Photos of old Black Asheville by photographer Andrea Clark. I’m thankful Andrea captured such a special time in Asheville’s Black history. Her photos hang in my restaurant and looking at them gives me a sense of joy and hope for the future.

Citric acid. I love citric acid. It’s the white powder that coats your favorite sour candy. It’s fun to use to adjust the acid in cocktails or to give your favorite spice blend a punch.

Brittany Howard – “What Now”. I can’t stop playing this funky album at the restaurant. It feels groovy and nostalgic but fresh. It’s fun to see people in our dining room getting down while they dine.

Hoka Ora Primo. These are my new kitchen shoes for as long as I can find them. Good kitchen shoes are nearly impossible to find and naturally, after 10+ hours on your feet, you experience discomfort. These foot pillows make me feel like I’m walking on clouds.

- Name

- Ashleigh Shanti

- Vocation

- chef, writer

Some Things

Pagination