On striving for imperfection

Prelude

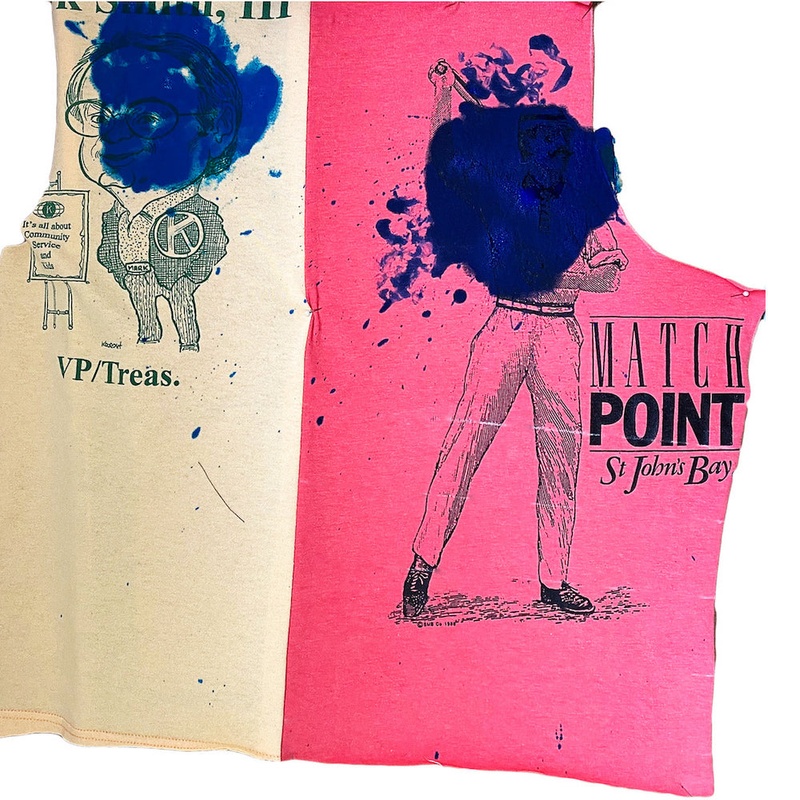

Moriah Black is a designer living in Brooklyn, New York. In dedication to the earth she founded ren6, a collection of one-of-a-kind apparel that values and protects the environment throughout every stage, from production to packaging. She only uses deconstructed vintage materials and dead-stock fabrics.

Conversation

On striving for imperfection

Clothing designer Moriah Black discusses why there will always be so much you don’t know about what you’re trying to do.

As told to Greta Rainbow, 2341 words.

Tags: Design, Fashion, Inspiration, Process, Mental health, Collaboration.

How did you start a clothing brand inspired by New York and sustainability, “by the raw edges, weathered surfaces, and the process of restoration”?

I grew up in Westchester and I was sneaking out to Tompkins Square Park when I was young. New York has always been where I saw myself. ren6 has been going on for about seven, eight years, starting when I got out of school—I went to Parsons [faux posh accent invoked]. It’s been a growing, evolving process that has involved a lot of self-discovery. I had to figure out what my true values were, which took unlearning the traditional strategies I had been taught about the industry.

What were you trying to push away and what were you trying to get closer to?

I was looking for meaning. I was taught from a very young age about what we were doing to our environment. What felt most authentic to me was to develop a practice that wasn’t going to be harmful to the planet. Then came the part of teaching myself how to go about it. Where is the fabric coming from? What’s the sewing process that’s going to be the most efficient, that leaves the least amount of waste?

What is the process of a ren6 garment?

First it starts with the sourcing. I’m going all over New York, everywhere from Salvation Army on Atlantic Avenue—one of the last places that has unique pieces for Salvation Army prices—to Goodwill, to Beacon’s Closet, to Metropolis in the East Village. Any clothes that are used or pre-owned are a possibility. It’s a process of sorting and finding what’s relevant and what could resonate in many different lives. I look for text and graphics that are positive, like “2099” and “TOMORROW” or an insignia of Dr. Martin Luther King. In some ways ren6 pieces act as timestamps.

After that I’m deconstructing the pieces I’ve found and sewing them together. That’s a process of composition, testing shapes out either on the body or laid flat, until it works. You could summarize it as sourcing, prototyping and playing, and production. And it’s always in development; I’m thinking of ways to make it less time-consuming but still real. I’m trying to come up with pattern designs and fits that are more unisex. There are no real rules, I make mistakes, this is a learning process.

How do you play within your work?

Many of these pre-owned garments have stains or other elements of wear that I have to work around and deal with, and that’s actually been an awesome way to develop a design. It’s like a baseline point of manipulation. A lot of trial-and-error comes from the creative constraint of existing imperfections, because ultimately it’s not about avoiding flaws but elevating them. It’s part of what makes a serendipitous composition.

I want to take only what I have and I want to use what’s around me. I don’t want to generate any waste that isn’t usable in some other way. I want it to be beautiful. I want it to inspire [the wearer and people who see the wearer], and for the message to promote wellbeing. I also want it to be of New York. It’s a lot to fit into one garment, but I’ve found a process that seems to make all these main goals possible.

Serendipity is one of those things that can’t quite be taught. Is your formal training still useful to you?

Of course, all the basic elements of complementary colors and best techniques, that’s important. But that’s not really where inspiration comes from. I’m heavily influenced by graffiti and street art. That was fundamental as far as composition is concerned—trying to incorporate random elements that don’t look random when you put them all together, like a wall with layers and layers of pieces by different people over time. I love that aesthetic. Because somehow it still visually works, and that’s the goal. It’s emblematic of human nature, the process of growing and dying and growing again, and leaving marks.

My [design] pinnacle is flowers. That came from this book I refer to constantly, The Philosophy of Sustainable Design: The Future of Architecture by Jason F. McLennan. The metaphor is a flower because it’s beautiful, it helps other organisms survive, it evolves with the climate and the weather, it adapts to its particular site but is still rooted in the earth. Nature is just genius, so…

What does it mean for a creative practice to be rooted in a geographic place?

New York is a core part of the design because that’s where I am. But ren6 could honestly be anywhere; it will take on the energy of that new place because it exclusively uses the material already existing there. I would love for it to grow into something like that. [New York] is my home and I obviously have a lot of nostalgic feelings about it, but beyond myself, the city has a concentration of amazing people and an industry ripe with freedom of expression. It’s both culturally diverse and unified, which has led to my feeling that we are all connected.

We’re a very story-driven culture, or race, or whatever. Narratives, nostalgia, and symbols allow people to connect with an art object or idea. I wish I knew more about where each piece I find came from. Though I am also happy just knowing that its background is rooted in New York. It’s a t-shirt worn by someone who lived here their whole life, or by somebody who was visiting for a weekend, or somebody’s friend who never made it here…That’s a pretty good start to any story.

People are the lifeblood of this whole project. I didn’t necessarily understand that until things got stale at one point and I remembered it was a disservice for me to isolate myself in a room working.

What does a typical day look like for you, if there is such a thing as ‘typical’?

It can be a stressful thing taking on a business like this. Self-care is part of what makes it work. I’ve done everything from breathwork to meditation in the morning to yoga to eating healthy foods to moving my body. Once that’s covered, I structure my time around the needs of the day. There are different needs for ren6 standard pieces and customs and collaborations, but it all requires a lot of composing before production. Other than the actual making, it’s administration. There’s a lot of outreach. I’m wearing all the hats so I do have to be the one self-promoting it, which is kind of the worst.

Why is it the worst? How do you promote ren6?

I just wish I was better at it. I’d like the work to speak for itself. I want to build it and have people come to it but I don’t want to feel like I’m pushing it down anyone’s throat. The best promotion I can get is from my clients. Which is a lovely way to do it and I love seeing their interactions with the work.

Do you work on ren6 full time?

Yes. I pretty much always have. I worked in service jobs for a couple years to supplement, which gave me the flexibility with my time to keep it moving forward.

It’s honestly really cool that you have 230 Instagram followers on ren6’s page. You haven’t gone viral and you aren’t making work with a “content” mentality that adheres to the algorithm; I think it’s testament that the clothes do speak for themselves.

I’m so lucky to be part of a community, and caring about the community is regenerative. The art relies on actual human beings. I am on Instagram and I manage the backend of the website and think about SEO, all of that. But it’s person to person when I meet someone who wants to bring me their old clothes and make a custom, or wants to collaborate. I wish that when I first started on ren6 someone had told me how important just going out and genuinely talking with people is.

What do collaborations look like?

Oddly enough, I wound up doing a lot of dance collaborations – I’m not a dancer. I learned there is a lot of freedom as far as having fun with the design but there are constraints as well; it has to be able to stretch and move and not fall apart. I worked with the choreographer Jessica Lange on a ballet where one half of the costuming was made from recycled painters’ rags from the artist José Parlá. It was really nice to introduce a sustainable approach because I think the concept is still pretty novel in that arena [of costume design].

So often I am bouncing off of my own head. Collaborative work is expansive. What can be difficult is the ability for people to communicate what they want. A lot of people don’t actually know what they want and they’re trying to find it through you. They’ll be like, ‘Just do you!’ and I love to do me, but I also want to understand how I can create a shared vision. Then we’ll all be happy.

How do you get the information you need to determine what they want?

You can’t rush those creative conversations. You have to make the time to have them.

Transparency is something I strive for. People don’t realize how much time it takes for every step of the process. They wonder why a piece costs so much, because you can’t see the hours it took on the train to get to a thrift store or the hours of trying different silhouettes and playing with text to make a poetic phrase. And I’ve got to pay myself a living wage.

How do you know when you’re successful?

That’s where it’s nice to be independent, it being all me. I base success on if I would love to wear what I’ve made, if I think it’s sick.

What is unique about clothing as a medium of expression?

It’s always been clothes. I was trying and trying to find a style that felt like me, and it didn’t really exist. I was a skater with a mohawk, wearing studs and those weird finger glove things, and I thought I was rejecting fashion—until I realized I was just as much a part of it as anybody else. As far as the practical technique, there is an ingrained freedom while also being rooted in logic and math. I love everything about how clothes move, how a garment needs a structure to have structure. It needs form to have function. There’s still a lot I have to learn about the craft itself and that is constantly growing with me. That will last my whole life.

I love how my work is with people in mind and providing the service of helping them feel more like themselves.

Does a commitment to sustainability ever limit you?

In some ways, of course, it would make things easier and faster [to deprioritize it]. But it’s so much better for me, personally, to be sustainable. I genuinely enjoy the unpredictability of my materials and I can’t imagine doing it differently. And then other things, like turning unwanted fabric into insulation instead of just throwing it away, are worth the time.

What else do you have to overcome to make your practice work?

If something doesn’t feel right I will spend way too much time on it until it does. As time goes on, I’m becoming better at realizing that while I may not have made exactly what I wanted to express, that doesn’t mean it’s not valuable. That requires self-understanding and self-knowledge. If something’s not working, it’s almost like a trigger. I’ll start to feel anxiety. To identify where that feeling is even coming from is emotional work. You have to acknowledge that you’re not okay in order to let it go.

What actions do you take when a piece isn’t working?

Put it down. Share it. Ask your small circle—your creative committee—what they think.

When I’m creatively stuck in general, I research. If there’s anything I learned in school, it was how to do that. There will always be so much you don’t know about what you’re trying to do.

What does your workspace look like? What do you need to work well?

Right now I’m in an office and there’s rods going all up the wall that are covered in fabric. That’s basically my palette. Being able to have my materials in front of my face is so good… There have been past iterations where everything is in piles on the floor and I can’t visualize a final stage. Even tucked away in drawers isn’t great. I need to understand what I have on hand to work with.

What are some of your creative goals?

I want to further my engagement with the community and be as restorative as I can. Whether that be employing people from marginalized communities, teaching workshops on how to dye your clothing using natural dyes, or even just repairing buttons… Clothes can be powerful.

Moriah Black Recommends:

White fir infused vinegar and/or terroir-based fruit paste

Obtain an owl hoot whistler and find the owls at dusk

Full body dancing with no inhibitions

Judge nothing

Mojave desert wild clay

- Name

- Moriah Black

- Vocation

- fashion designer, founder of ren6

Some Things

Pagination