On always evolving

Prelude

Alex Turnbull has done a lot of different things. Early on, he was part of the experimental band 23 Skidoo. He skated and DJ’ed. He trained and taught martial arts. He was one of the founding members of the International Stüssy Tribe. He and his brother, Johnny, started a record label, Ronin, but as children of two acclaimed contemporary artists, William Turnbull and Kim Lim, they now manage the estates of their parents. Recently, Alex launched his debut film, Beyond Time, about the life and work of his father. He is currently at work on a new film, one that would chart the rise of street culture. He lives and works in London with his wife and his two kids.

Conversation

On always evolving

DJ, musician, skater, and filmmaker Alex Turnbull discusses what it means to do a lot of different things, and why it’s healthy to strive to defy description.

As told to Ken Tan, 1721 words.

Tags: Art, Film, Music, Beginnings, Collaboration, Inspiration, Multi-tasking.

You’ve been involved with creative projects all your life. Tell me a little bit about how you started.

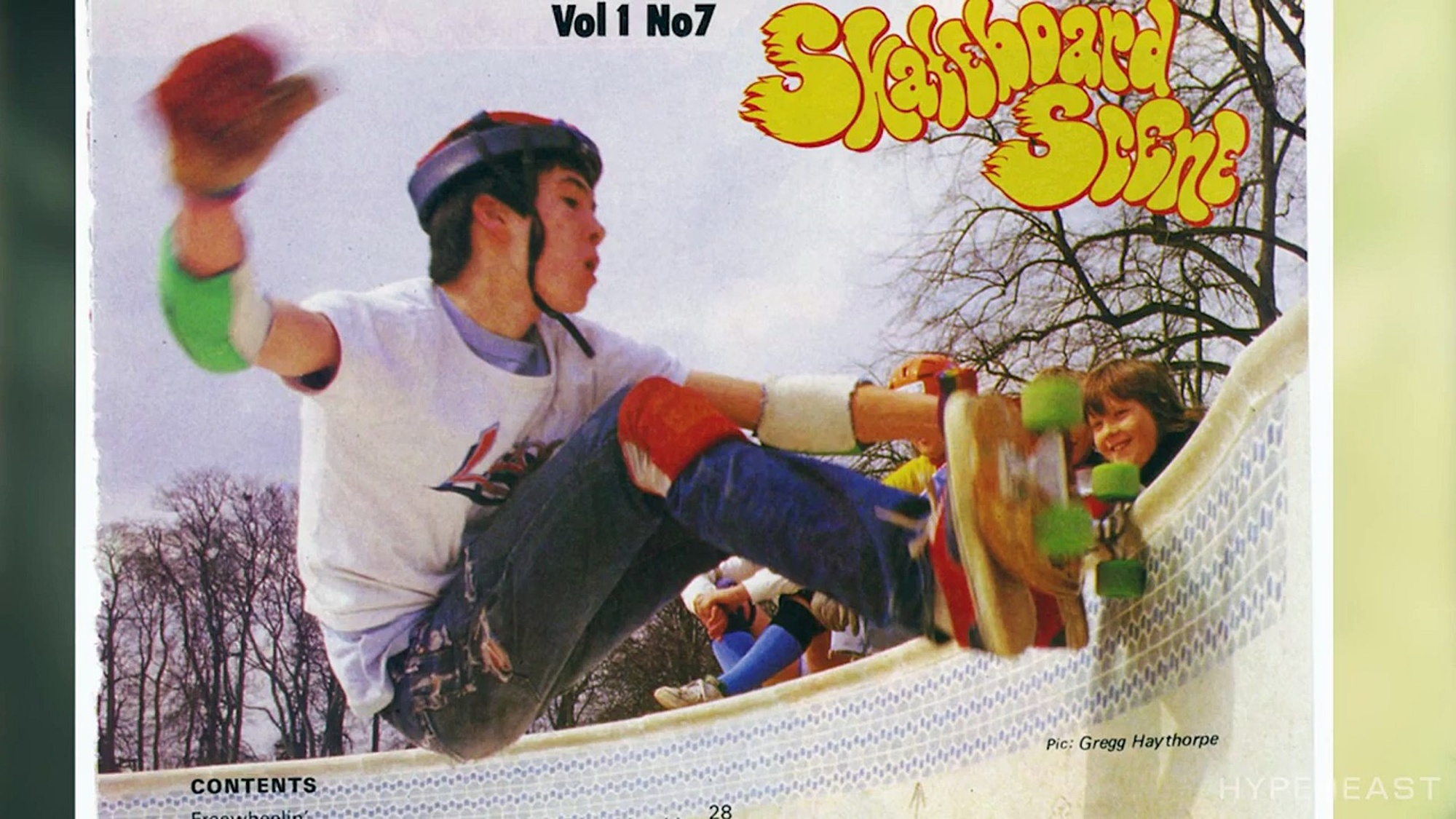

Skating came first. I was young, like 15, when I became part of the first wave of British skateboarding. That was around 1976–77, about the same time as the Dog Town guys in America. That was an amazing time. Skateboarding had such a big cultural impact and influenced a lot of modern contemporary culture. I first met a lot of the people who impacted my life through skateboarding. I think the brotherhood in skating is a really positive influence.

How did you find your way to DJing?

First, I was a drummer for our experimental band, 23 Skidoo. I was always into funk drumming, like Jaki Liebezeit from the German band Can, which actually is my favorite band. I think in a way Can, with its non-rigidness, probably set some of the parameters for what 23 Skidoo became.

I got introduced to DJing in 1983 by the way of hip-hop. It was called electro in the early ’80s and you couldn’t really hear it anywhere. I was going to the Shaw Theater in Euston Road where they had DJs Red Alert and Afrika Bambaata. It was the first time I’d ever seen somebody cut up breaks, taking the best drum bits from a record and making them into an elongated segment of music. I was just blown away. For 23 Skidoo we used to use a lot of cassette loops. Essentially, we would use old Walkmans, which had the recorder and the little speaker. Then we’d cut and splice cassette tapes to make loops. So it was mind-blowing for me to see people manipulate sounds and beats live. It was completely new!

I bought two belt drive turntables and hot-wired them into the back of my amp. Then with two or three hip-hop records I learned to mix. It was probably four years until I had two Technics direct drive turntables. That was a part of the process that was quite interesting in terms of having to be resourceful. Every hotel lobby has a set now, and it’s kind of a cool accessory.

Right, like “Yeah, we’ve got this DJ set up.”

You know, that just wasn’t the case then. The equipment and DJ mixers were like gold dust. You’d have to go to New York to buy GLI mixers. It was a time of discovery. Eventually, we started to play out. We did some amazing all-night parties in abandoned buildings and stuff like that.

Have you always known that music would be a part of your path? Even as a kid?

No, not really. I grew up with two parents who were artists from different parts of the world: Scotland and Singapore. My brother and I grew up with art around the house. We washed sculptures for pocket money, and there were 20 huge steel sculptures in the garden waiting to be washed. I think our parents didn’t want us to be artists because there was no money in it. You couldn’t imagine the possibility of making money being an artist back then.

My dad tried to get me to play the violin, but I really wasn’t very good. I wish I’d learned to play the piano, but that just never came off as an option or something I ever thought of until much later on. I played the bass first, because of Paul Simonon of The Clash–he was just the coolest motherfucker. So, I played the bass but I realized that what I was really into was drumming. I got a drum kit and taught myself by listening to records like Fela Kuti and A Certain Ratio.

How much did experimentation and anti-conformity inform that early part of your creativity?

A lot, possibly too much sometimes. I think that’s part of the post-punk generation we grew up in: 1978-1984. If you were cool, being commercial or a “sell out” was the worst thing that you could be, for us anyway.

We were the press darlings, and they were writing about us all the time, kind of making stuff up about us in the gossip pages. And we just wanted to be really serious and taken seriously. Our first record went straight to number one in the independent charts. After that, we kicked out the singer and the guitarist, shaved our heads and did percussion on scrap metal.

We were trying to challenge the format. For example, we wouldn’t have gaps between the songs or we did a tape loop at the end so there wasn’t really a chance for audience interaction. We were trying to push boundaries.

Now, music has become more about satisfying the listener. You can access everything at your earliest convenience, so the way you relate to music is different. Previously you had to save up to buy an album, which would have been the only new thing you had for three months to listen to.

Tell me about how you met Shawn Stüssy.

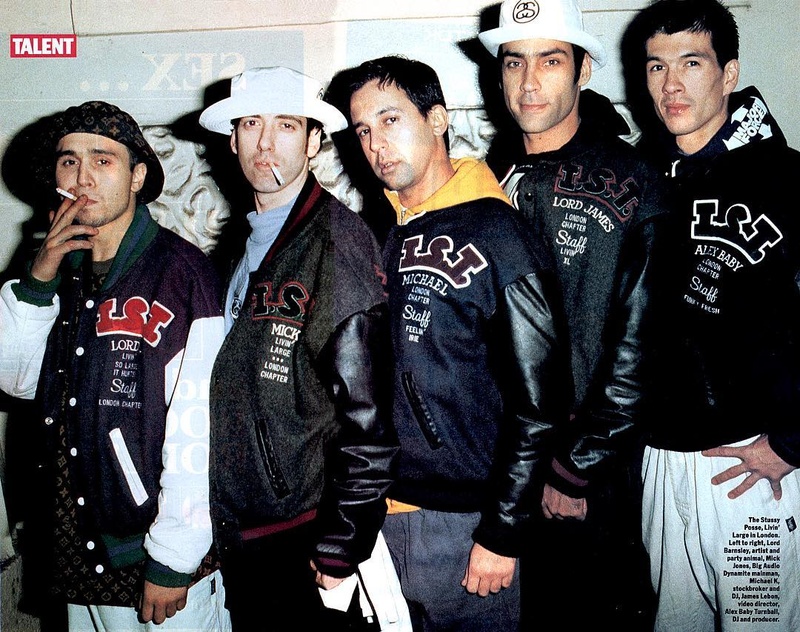

Shawn’s an inspirational guy. He’s an old friend whom I’ve known for like 30 years now. I remember I was in New York with my friend Jules Gayton back in 1986–87. Jules was staying with this guy, Jeremy Henderson, whom we used to skate with. They hooked me up with Paul Mittleman who was working with Shawn, and that’s the first time I discovered the brand Stüssy. There was nothing like that before Stüssy. You were just like, “Wow. I’ve gotta have that.” At that time, no one knew about it, only five people had it. It was really super. Then quite quickly, Stüssy became something big. It set the blueprint for what’s come since—Bathing Ape, Supreme, etc.

Anyways, Paul and Shawn came over to London to this club called Enter the Dragon where I DJ’ed. I gave Shawn a mixtape, which had a sample scratch “Alex, baby” cut from an Alexander O’Neal record. Shawn sent me an International Stüssy Tribe jacket with the name “Alex Baby” on it. That just stuck as my DJ name from that point forward.

You recently made a film about your dad, William Turnbull, which I understand is your first film. Can you tell me a little bit about that process?

The film happened quite organically. I’ve always wanted to make films, like a kung-fu flick, which I still hope I’ll get to do one day. I didn’t go to film school, so I don’t make films probably the way one should. In a way, if you’re into beats and sounds, visual editing will happen on some level. I made the film with an artist and musician friend, Pete Stern, who I know from the skateboarding days.

My dad and his generation were a stoic bunch who didn’t really talk that much about themselves. I had to go and uncover all these people who could fill in different historical bits to the story. What we achieved was this incredible revelatory film that talked about my dad through a post-war lens. It was narrated by Jude Law with a soundtrack by 23 Skidoo and shown on BBC4.

It was truly an amazing experience, and in the process of making it, I became the repository of information on William Turnbull—dovetailing into me now managing my parent’s estates.

What’s the breakdown of your creative life right now?

For a while, the management of my parent’s estates was taking up a lot of time, because it had to be done. The whole process of going through two lifetimes of work in order to curate and present them in a way that can measure up was really important for my brother Johnny and I.

Now that that’s actually going pretty well at the moment, I’m concentrating on a new film project that will look at the birth of street culture. I’ve now got an all-star cast of individuals who have lived through it to share their interesting perspectives. It’s not a definitive history, but rather a web of influences and origins.

I’d love to do more music, and I don’t get to do enough martial arts anymore. I still train but no longer teach. Also, to be present for my wife and my kids as they grow up. I’m really excited about what the future holds.

Do you think your martial arts has a little bit to do with your focus?

I’ve been training since 1981. Being involved in music, and having a counterbalance certainly kept me out of trouble over the years. Whether it’s skating, or martial arts, or DJing, I’ve gotten pretty good at not mucking around in any of those other things. There’s a validity and pride for the things I’ve done, and respect for the people I’ve worked with.

It’s the modern life now I guess; people do multiple things. People didn’t do that before. I think probably if I’d done less I might have got further because it would have been easier for people to go, “Yeah, you’re that.”

Right. To be recognized for one thing.

I’ve always kept moving, to not be in a rut. Evolving. You know what I mean. Somehow all these things fit together—when I was teaching martial arts for a lot of years I was understanding my own body mechanics, and as a result my drumming got a lot better. It’s the same fundamentals.

Perhaps that’s one of the benefits of getting old: you apply the new skills you learn. When I got to my 50s, for a lot of people that means going downhill, but I started to train with an amazing Vietnamese Muay Thai instructor Pat Le Hoang and was able to take my Thai boxing to a whole new level. You know, age doesn’t stop improvement.

Alex Turnbull Recommends

Music: Can, the greatest group of all time

Art: Kim Lim

DJ: DJ Da Capo

Martial arts: Shogun Assassin

Skate films: Dogtown and Z-Boys, Future Primitive, Blessed

- Name

- Alex Turnbull

- Vocation

- DJ, Musician, Model, Skater, Martial arts practitioner, Filmmaker, Managing the estates of William Turnbull and Kim Lim

Some Things

Pagination