On why you should start your own unconventional art space

Conversation

On why you should start your own unconventional art space

Curator, writer, and educator Ceci Moss on starting Gas, a contemporary art gallery in a truck, and the punk ethos that keeps her driving forward.

As told to Willa Köerner, 3770 words.

Tags: Curation, Beginnings, Business, Inspiration, Success, Adversity.

How did you decide to start Gas, a contemporary art gallery inside of a truck?

Well, I moved to Los Angeles and knew I wanted to start an art space. I didn’t know exactly what it would look like or how it would evolve. Once I moved here, I basically spent six months meeting with people. I met with friends of mine who started art spaces, and I met with artists all over the city to get a feel for the landscape here. Really, it was a listening exercise for me to get a better sense of the arts ecology in LA—what exists and what doesn’t exist, what are people’s concerns, you know, all of that stuff. I needed to do that to see what would be feasible and sustainable here.

Originally, I thought I would move into a storefront and live in the back and have a gallery in the front, because that seemed like a model that I could actually sustain. But the more I talked to people, the more I started to recognize that LA has these clusters of different art communities around the city. And I didn’t want to be stuck in one location. I really wanted to work with a lot of different people, and throughout these conversations, it became apparent that it’d be hard to do what I wanted to do in a stationary gallery.

Before moving to LA, I lived in the Bay area for a long time, and there was a space called The Bus that an artist named John Benson ran. He had an AC transit bus that he gutted and turned into a performance venue, and I helped set up some shows for him. That was so inspiring. They would just park it anywhere, and have these punk and noise shows all over the Bay. Another space that I was looking at was Bed-Stuy Love Affair, a gallery in a converted RV started by the artist Jared Madere. He was doing solo shows with artists where he’d hand over his RV and let them do whatever they wanted.

The mobile thing just seemed to be a natural fit for LA. The other thing that’s great about it is my overhead is low. My main expenses are parking and storing the truck, insurance, gasoline, and maintenance. Thankfully I’ve only had two big issues with the mechanics of the truck. Otherwise, it’s been pretty straightforward.

So yeah, because I’m a one person operation, this model allowed me to actually start a space and sustain it. I do three shows a year, which is nice, as I’m not trying to turn over shows constantly. I’m also only open one day a week, so it’s not like, you know—I have so many friends who run galleries where they’re sitting by themselves at a desk for 30 hours, and it’s like, why do that to yourself? It doesn’t make sense.

“Fuck the Patriarchy” Installation Shot (Photo by Flynn Casey)

What has been the most challenging part of getting Gas up and running?

Probably the biggest challenge has been the fact that I’m not a mechanic. I had to learn about truck mechanics, diesel engines, and just about cars in general. I lived in New York for a long time, so I never really had to think about that stuff.

The other thing was, even though I worked in non-profits for a long time, this was my first time starting a non-profit. Here in LA, there’s a great organization called Public Counsel. They have free and discounted workshops to teach you the basics of starting a non-profit. They also have pro-bono lawyers who can walk you through different steps and stuff.

At this point, I’m a fiscally sponsored non-profit through Fractured Atlas. Learning how to set that up was like Small Business 101. Again, I came into this project with a significant amount of curatorial experience, but there were a lot of things I didn’t know and I had to learn. It wasn’t like those unknowns created a barrier—they were just new skills that I had the opportunity to gain.

I’ve been lucky. My truck actually belonged to a woman who ran a gallery out of it already, and she had it on the market for, I don’t know, eight months or something. No one wanted to buy it. She gave me a significantly discounted price, because she wanted it to continue on as a gallery. So when I bought it, it was totally set up, and I had to do very little to build it out. It would have been a much more costly and difficult process had I not found that truck.

The other thing I should mention is that when I first moved here, I was in a really bad car accident, and I got a $10,000 insurance settlement. That basically paid for buying the truck, and was the seed money for getting the project off the ground.

“take care,” Installation Shot

It sounds like there was some luck involved—not that it’s lucky to be in a car accident. But it’s lucky to get $10,000 if you need $10,000, and then to find a truck that’s already set up for what you want to do.

It was weird. I had kind of a bad luck year—the car accident was part of my bad luck. But it all turned into good luck, you know? So, it was one of those things where everything kind of came together in this way that felt fated. I just was really lucky that a bunch of things lined up for me, and when it was happening, I was like, “Oh my god. Am I actually doing this? I guess I’m actually doing this now.”

Would you say what you have going now is right in line with the vision that you were originally pursuing when you decided you wanted to have a mobile gallery?

Yeah, I mean, I feel like I am doing it. I’m learning new things all the time, and I’m hoping that what I present to people is a model for realizing an art space that isn’t fully entwined and embedded in a lot of the problems that currently exist within the art world. We’re in a time when people can’t do business the way that they’ve done it before, and I’m hoping that my space—even just in a tiny way—presents an alternative for how you can support artists. I do pay all the artists that I work with. Not a lot, but a little bit. I just want to present a different vision for how you can support and show and create work that isn’t rooted in an oligarchic structure. You don’t have to necessarily follow the rules.

Beyond landing on the mobile gallery model as one that would suite both you and the LA landscape, I’m curious about the other ways you’ve taken a practical approach to developing your model?

I worked in non-profits forever. Burnout is real, and I think I wanted to create a project that I could actually sustain as a single person doing it. My objective is exhibiting art, talking about art, and giving artists opportunities to experiment and try new things. Because I don’t have commercial aims, I don’t need to be open every day. On the flip side, it makes more sense for me to be open on the weekend when more people can see the show, and it makes sense for me to be stationed at another gallery’s opening when there are like 100 people there.

So yeah, I make these sorts of programmatic decisions while trying to be conscious of my own time, and all the other things that I’m balancing. If I was renting a space that cost $2,000 a month, it is inconceivable that I could sustain something like this. But in LA, there are a lot of art spaces in unconventional venues. There’s a curator, Seymour Polatin, who has a project called gallery1993, and it’s in a 1993 Crown Victoria car. And another curator, Don Edler, has a space in an elevator shaft called Elevator Mondays. It’s not like I’m the only person in this scene who’s thinking along these lines. There are many other artists and curators who are experimenting with what an exhibition venue can look like, and who also share similar politics and sensibilities.

Olivia Mole, Dud Ankress, 2018 (Photo by Flynn Casey)

How do you define success with a project like this? How do you know when things are going well, vs. when things need attention?

A lot of it is just the feedback from the artists who I work with. The biggest compliment I’ve gotten so far with this project is when I meet an artist and they’re like, “Oh, you worked with so and so. She was telling me about the space and how fun it was to collaborate.” If I either directly or indirectly get positive feedback from the artists I work with, that is a metric for success to me.

Another metric for success is I want people to look at the model that I’m working with, and see how doable it is. I want to inspire other people to start their own spaces, because I think that a healthy art scene involves a lot of different voices and perspectives.

If you think the only people who can start an art space are those who have millions of dollars in the bank, and if that’s the barrier to entry to create the kind of program you want to create, that’s ridiculous. Unfortunately in the art world at large, there’s a lot of gate keeping, and a lot of problematic class structures. I’m not interested in perpetuating those. I hope that what I’m doing is just a grass-roots type of curation. I hope that people look at what I’m doing and they’re like, “Oh, ah ha. I can start my own project.”

So, I guess simply a metric for success is people also being like, “Oh, I saw your show. I decided to do something similar. I’m doing these trunk shows,” or, “Oh, I saw you on Instagram. Then, I was inspired to have these salons in my house.” That kind of thing. I want more of these kinds of unconventional spaces to exist, because that’s actually the heartbeat of a healthy art scene—not having another Gagosian in your city.

Olivia Mole, Dud Ankress, 2018 (Photo by Flynn Casey)

With that in mind, how do you plan to sustain this? It sounds like now you’re basically able to fund this with money from your settlement, and I’m wondering, how will you keep it going?

In addition to each show, I usually release a fundraising edition, like a print or an art object. We’ve done a scented car air freshener (by Ian James), a collapsible water bottle (by Susanna Battin and Kate Kendall), a poster (by Cara Benedetto), a bumper sticker (by Roy Martinez), and a print on seed paper that blossoms into a flower garden (by the Institute of Queer Ecology). Each one is affordably priced, usually about $10. But if I sell 100 of them, then that covers the artists fees for the show, and a lot of production stuff.

Also, so far all the shows have been group shows with almost all pre-existing objects. I don’t have the budget to commission new works, but this year I applied for a ton of grants in the hopes that I will be able to commission new projects. I’m really conscientious of people’s time and labor. That’s why with all the shows that I’ve organized so far, I’ve tried to be thoughtful and careful about what I ask of the artists I work with. I am operating with pretty much no budget, and I pay a small artist’s fee. I also volunteer my time. So, yeah. That’s how I’ve been doing it so far, but I’m hoping it will grow, either through grants or by selling out all of our editions. I’m still working it out.

There are a lot of steps that go into producing these shows. But it’s like, “Oh, I know this one fabricator who can make a pedestal for me at a discounted rate, because they’re a friend.” I was involved with punk and music for a long time, and I feel like my approach reflects how things get done in those spaces. You know, where it’s like, “Oh, you can loan me this, or I can help you with that.” That’s basically how I’m able to produce these shows.

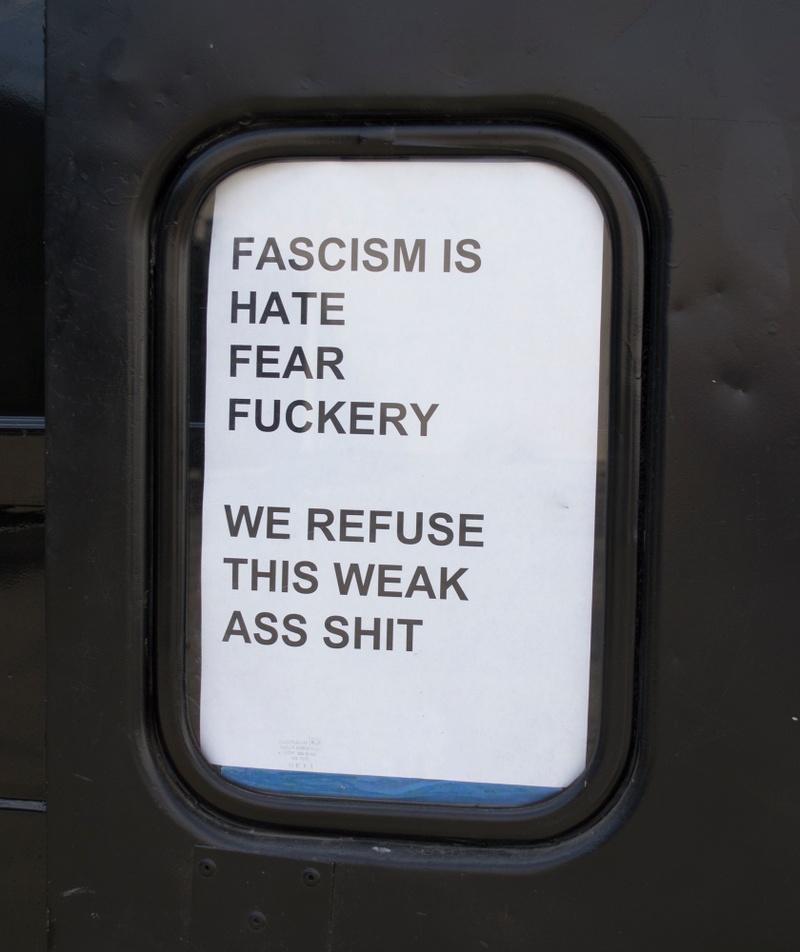

YERBAMALA COLLECTIVE, BURN IT ALL DOWN: AN ANTIFASCIST SPELLBOOK, 2017 (Photo by Flynn Casey)

What would you say to someone who asks you why you’re volunteering your time and energy in this way? How do you explain this project to people who wonder what’s in it for you?

Well, that’s a person who fundamentally just doesn’t understand. I’ve spent my entire life supporting artists and being around artists. What’s in it for me is I want to create experiences for other people that are meaningful, and if I can do that, then I’m happy. That’s what I get out of it. That’s literally the point, and that’s also, I think, what every artist I’ve ever worked with also wants out of their practice: just genuine human connection, and intellectual and emotional stimulation. It’s about connecting to other people through these shared experiences that are really beautiful and important and meaningful.

What else is there, really? I feel like there’s a shared sensibility there. If you don’t understand that, then we’re not looking at it through the same lens.

Before you started Gas, you were working as a curator for different institutions, including YBCA, Rhizome, and the New Museum. Do you think you could have done something like this before working in institutions, or before you developed your visibility and experience as a curator? Do you think people, especially curators, should aspire to work with these more established organizations and institutions, or do you think it’s just as valid to start your own thing?

I think it’s just as valid to start your own thing. I mean, for sure, my network’s a lot bigger and I have maybe some more doors open for me because of the institutional experience that I’ve had. But honestly, the thing that I’ve learned the most from working at those spaces is administrative stuff. Like, how to write a loan form, how to deal with shipping, how to plan an exhibition, how to deal with people’s expectations, how to communicate, all those things.

I feel incredibly grateful that I had the luck to have those experiences, and I’m sure they helped me to develop these basic management, administration, and more boring skills that you might need to start a space. But I don’t think you necessarily need to have those experiences before starting your own space.

Susanna Battin and Kate Kendall, Gas-for-Water, 2018 [Performance, September 15, 2018]

How has starting your own space been helpful for your sense of self?

One of the things I encountered a lot with when I worked in institutions is that a lot of institutional curators will collapse their own sense of self with the institution they work for. Then, it spirals into this unhealthy psychological relationship to that institution. Really, institutions and organizations have a life of their own, and you are separate from that. I did wonderful things that I’m really proud of when I worked at Rhizome, the New Museum, and YBCA. And there are other people there now who are doing wonderful, amazing, incredible work, because that thing is still living. It has its own life.

When you work for an institution—whether it’s an institution that you started, or not—it can affect your sense of self. I don’t know how long this project will last. I hope it lasts for as long as I can sustain it. I hope it’ll have its own life after that, and that it’ll be something that people remember, like, “Oh, that was such a cool show,” or, “Oh, I was a really young artist and I got this opportunity, and it led to this other opportunity.” I mean, that’s just what we do. It’s not about me. It’s more about the production of art, and the creation of the conversations and communities and experiences that happen around it.

I’m sure a lot of people are frustrated because there are so few curatorial jobs, and they want to curate and they’re stuck in some job they don’t really like. What do you think it requires to actually be successful in launching a new space?

You have to be patient. And, you need to be comfortable with failure and things not going your way all the time. For anyone working with artists, you have to be a good, empathetic listener. Plus, definitely, you need to have a positive attitude. There’s disappointment all the time. Like, I apply for grants all the time, and I usually don’t get them. You just keep applying. In the same way, you just have to continue going through things and not get disappointed if you don’t get the thing that you think you deserve the first time. Just be persistent.

I also think just being creative in terms of how you problem solve, like, “How do I get free photocopies? How do I save on shipping?” Having a day job can also help, especially in the beginning. That’s the strange thing with curating—there are all these MA mills where people pursue degrees, and then expect that there’s actually a job market. But if you look at the history of curating, people have always run salons or alternative spaces to show art.

It’s not like going and getting a law degree to become a lawyer, or getting an MBA to become a banker. You curate art because you care about it, and because you want more of it to exist in the world. I mean, ideally there would be a support system for funding that, but that’s not, unfortunately, the reality that we exist in. Despite that, it doesn’t mean you can’t continue to try to make these spaces happen. So basically, find out ways to do things that are sustainable. You don’t need to rent a gallery to show art. You can do it in your home. You can do it in a park. You can do it at the beach. Like, who cares?

If the point of these spaces or these exhibitions is really to connect with other people around art, you can make that happen. Again, my background was in the punk scene. People had generators, and they’d have shows in a cave or at the beach. If this is what we want to have in the world, then we must create the space for it. And the spaces that are opened up with that kind of energy and that kind of intention are really beautiful, really important, and really different. And really free, too. I think if you can just approach things with that open-minded perspective, it’s the best way forward.

“Fuck the Patriarchy” Installation Shot (Photo by Flynn Casey)

Ceci Moss recommends:

-

Women’s Center for Creative Work’s A Feminist Organization’s Handbook - The Women’s Center for Creative Work is an organization in Los Angeles that cultivates the city’s feminist creative communities and practices. They’ve been absolutely instrumental in nurturing so much of what is coming out of Los Angeles. They’ve pulled together their insights from starting the organization into a handy guide, so that others can learn and grow from their model.

-

Machine Project x Common Field’s Guides - Machine Project is an inspiration for Gas, in terms of their attitude and approach. I’ve been avidly following their activities since the mid 2000’s, and I covered their work when I was Senior Editor at Rhizome. Machine Project closed recently after fifteen years of robust programming but they’ve collaborated with Common Field to produce three handy guides on starting an art space, curating a show, and running a workshop.

-

Beth Pickens Your Art Will Save Your Life - Beth is the secret sauce to the health of the Los Angeles art scene. Almost every artist I’ve met with during my two years here has attended her grant writing or “Making Art During Fascism” workshops, hired her for various projects or consulted with her about their projects. Her work is a testament to the immensely positive impact one person can have. For those who aren’t lucky enough to share a city with Beth, she wrote a book compiling her sage advice and tireless cheerleading for art and artists. In these dark times, I highly recommend it.

-

Jennifer Armbrust’s 12 Principles for Prototyping a Feminist Business - Another Angeleno, Jennifer Armbrust, is thinking through alternative, feminist business practices. Her message about changing larger power structures through the establishment of a feminine economy takes on many forms - from a DIY business school to consulting - but her “12 principles” distills it to the basics.

-

adrienne maree brown Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (Chicago: AK Press, 2017) - This book! I’ve heard that a few Gender Studies departments have been buying them in bulk to distribute for free to students, and I’m not surprised. brown is a community organizer and activist, deeply influenced by ecological models and science fiction, especially the work of Octavia Butler. Her book is essentially about finding ways to connect with the present to nurture social change as emergence. Her read on temporality and the horizon of possibility echoes Jose Estaban Munoz, while her ecological framing reminds me of Donna Haraway. Some gems: “What you pay attention to grows” “There is a conversation in the room that only these people at this moment can have. Find it.” and so much more…

- Name

- Ceci Moss

- Vocation

- Curator, Writer, Educator

Some Things

Pagination