On the power of building something with friends

Prelude

Founded by Constanza Valenzuela and Jack Radley, ACOMPI is a global curatorial project based in New York City. ACOMPI comes from the Spanish word acompañado, meaning “in company.” ACOMPI foregrounds interdisciplinary practice and collaboration and serves as a youth-oriented, community-ingrained platform to expand the intersection of independent curatorial practice and site-responsive public engagement. ACOMPI celebrates narratives of immigrants, youths, and artists working in interdisciplinary means not satiated or supported by the market.

Conversation

On the power of building something with friends

Curatorial duo ACOMPI discuss creating a path outside of institutions, balancing your day job with your passion projects, and the importance of doing it together.

As told to Mikki Janower, 2424 words.

Tags: Art, Curation, Collaboration, Multi-tasking, Inspiration, Independence, Day jobs.

We’re doing this conversation at Miriam Gallery, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. It’s the site of one of your exhibitions. Do you want to start by telling me about that exhibition, Ocultismo y barro?

Constanza Valenzuela: Miriam invited us to curate a show a year ago. We were excited about a group of Latin American immigrant and first-gen artists and noticed a lot of them were using ceramics and interrogating its histories. We were like, “Okay, let’s do a show about clay and its mystical qualities. Not just clay, but also what it has meant historically in terms of pre-Colombian sculpture and in terms of traditional pottery.” A lot of clay effigies were used in a more spiritual way than they’re shown now. You see them differently in museums; they’re kind of removed from their original context. So we were trying to pay homage to the mysticism around the pieces. I’m from Ecuador, and I think a lot about syncretism in terms of how Catholicism exists there, molded into something new with lots of indigenous influences; it’s still called Catholicism, but it’s something completely different. And that indescribability and that lack of theoretical understanding is where occultism comes in.

Jack Radley: I would add that Miriam is unique in that it’s run by artists (Jaclyn Dooner, Paige Landesberg, Simón Ramírez Restrepo). It has a DIY ethos within a sterling space. You get the best of both worlds. And it really was a collaboration. Everything we do is about collaboration.

You guys collaborate within a network; a lot of the artists in this exhibition are artists you’ve worked with before. Do most curators build long-term working relationships with artists they work with? Or is that something you guys set out to do?

CV: So much of our work is spending time with artists. We want to know about the process, we want to do studio visits, we want to hang out. Friendly collaboration and relationship building is where you realize, “This is who we fuck with, we like what they’re doing and where they’re headed; and we want to support them.”

JR: Deep collaboration is rhizomatic: it doesn’t have a closing date. It’s sustained and it’s nimble. It lies in the cracks of conversations and connections, and entails mutuality in the name of realizing something that you can’t achieve alone.

Installation view: Mateo Arciniegas Huertas: Domingo a las 4, 2021, PO Reinaldo Salgado Playground, Brooklyn, NY. Courtesy the artist and ACOMPI.

You two have a particularly beautiful working relationship. How did you build it, and how do you manage it day to day?

CV: Jack and I met working together at an arts organization in New York. I was straight out of grad school and Jack was straight out of undergrad, and we’d both had a little experience in the industry, but we were naive in our thinking about how institutions operate. They can be slow in putting together projects and hierarchical in the decision making—an existing organization wasn’t the space to realize our own ideas in real time. Our friendship came out of being young and excited and eager to be in the world and make stuff that we care about and not finding that creative fulfillment in our entry-level jobs, even though they were highly regarded.

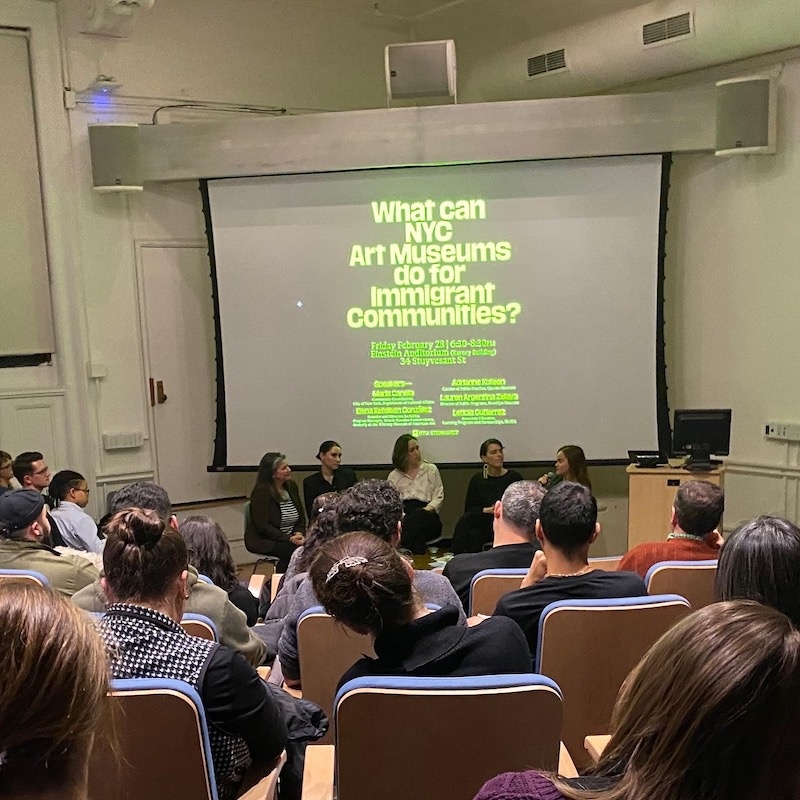

Our first project was based on my thesis on what New York City museums can do for immigrant communities, and I had talked to my NYU program about doing a colloquium. I’d done independent projects before, but it’s a lot of work and a lot of pressure to be a lone curator, and I didn’t have the time. Jack was like, “No, let’s do it. That sounds dope, and I’ll help you.” So we put it together.

It was a really positive experience. We went to the Department of Cultural Affairs to meet with our amazing moderator, Maria Canela, who is a living, breathing example of an immigrant who learned English from the programs run by the Queens Museum. The museum professionals who spoke on the panels were all so excited to participate. The colloquium was a huge success: it was the best-attended the program had ever run. We got our first piece of press. And our collaboration was magical. After that, we started applying to open calls.

JR: The pace outside of institutions lends itself much better to our ambition and responsiveness—we also recognize the fire in people before a lot of organizations would take a chance on them. We’re not driven by the market. We both have full time jobs, and our shared work happens beyond them. When the clock hits six or seven, it’s our second shift that’s just beginning. Because of the time and the care it takes, it has to be fun.

CV: Yeah, we’re not making a living off this work, and we won’t be in the near future, so it has to be fun. We genuinely love going to shows and talking to artists. We have a robust DM thread where we’re always sending art and being like, “Yo, check this out,” “Look, what about this idea?” “Look at this artist, and this artist,” “Look at this theme,” and we start pulling threads of the themes that we see in the art world. We also do field trips—what do we call them, retreats? We go to museums and ask each other what we think. We’re in constant communication, but we’re homies and we catch up and we laugh. We have so much genuine interest. It doesn’t feel like we’re working all the time.

JR: The DM may live in infamy as a flirtation device, but it’s also an archive. When we’re looking for ideas, we scroll back months and months and months to see what we’ve talked about. It’s a good way to flag something or to share it with each other. The DM is a language we speak: [to Constanza] if you send me something over DM, you don’t have to write anything; I often know what you’re thinking about.

CV: We’ll send these cryptic messages. It’s like mutual note-taking.

Mateo Arciniegas Huertas, Pagando el arbitraje, 2021. Courtesy the artist and ACOMPI.

How did you get so good at talking about your work?

CV: That’s what curating is. We’re just used to it. Artists talk a lot about their work, and they invite people to their studio to talk about their work. We do pitches, too. And we both work for institutions, so we see how institutional conversations happen—often it’s just an email, a deck, and a connection.

We’ve applied that methodology to our own practice. We’ll be like, “Yo, you have available space!” We got the space for Canal Street Research after I drunkenly saw this huge empty storefront. I took a picture of it—it was like 2:00 in the morning—and I said, “Jack, we should email them.” We sent them an email saying, “We would love to talk more.”

Ultimately, it was a great collaboration opportunity. We do offer a service. Venues lend creatives real estate and services, and creatives lend venues the culture that young people want to see.

JR: You have to speak about art without artspeak. The language you speak to the venue hoping to use their space is different from the language you speak to the artist; is different from the language you write on the press release; is different from the language you use to text the landlord when the heat doesn’t work … I guess if press releases had as many f-bombs as cries for heat, people might actually read them.

CV: And you have to reach a mutual understanding in the most caring way possible. Our work is to demonstrate that art isn’t just what you see. Like, we did a show with Mateo Arciniegas. He was taking pictures of his soccer team members; soccer was how he found camaraderie with other Latin immigrants in Bushwick. Mateo was like, “I have this series of portraits that wouldn’t fit in a gallery. I want [the show] to be for the people I play soccer with. They wouldn’t go to a gallery exhibition.” So we did a show in the soccer field where they practice. This was a way of not using art spaces or jargon-y words, yet trying to get people to understand that it’s more than just pictures.

‘What Can NYC Art Museums Do for Immigrant Communities?’ Colloquium at NYU, 2020. Courtesy ACOMPI

You work with a lot of immigrants, first-generation artists, and people working in historically underrepresented disciplines. Would you describe your work as mission driven?

CV: We talk so much about our mission, our integrity, and our driving forces. But we aren’t quick to define that mission. We’ve let our practice grow and take its own form through different projects. I think constant renegotiation is important. We’re thinking about the short term and long term, but being adaptive.

JR: I think our work is artist-driven. The artists, their ideas, and our collaboration is most important.

CV: Our work is about the relationships that we build, and allowing artists to think beyond the traditional exhibition space.

JR: I don’t think we have a mission that we try to fit art into. Art is the mission. It is a backbone that extends outwards and has civic potential.

CV: We’ve been talking about how we want to go to church. I want to do stuff that’s kind of noncommercial, or if it’s in a commercial space, I want to find a curatorial schematic that goes beyond just formalism or medium-driven. It’s more interesting that way. We do things that we would want to attend, things we think are cool; what we want to work on and what we want to talk about.

Do you draw any boundaries between your work life and your extra-occupational life? Are there moments when you take off your creatives’ goggles?

CV: We’re almost too deep in: it’s hard not to dissect anything through a curatorial lens. I would say that the art world as a whole is quite intertwined.

JR: Any time we would want to take off “creatives’ goggles,” we reassess those goggles. Loosen the straps, Windex the lenses. We should be able to be creative all the time; it’s just [a matter of] redefining what that is: hanging out with artists, having a couple drinks, coming up with an idea. I don’t want to be generating ideas from PDFs over email. I think you said this the other day, Constanza: let’s just hang out and see where things go.

CV: Yeah, it’s like, let’s just—

JR: —spend time together.

CV: Without an agenda or anything planned.

Do you have tips for creative people trying to work outside institutions? Even with institutional connections and backgrounds, you’re good at getting outside the system.

JR: I would say find people you trust and build it together.

CV: Yeah. We always say it’s not DIY. It’s DIT: do it together, which we got from a curator colleague that we respect a lot—Eva Mayhabal Davis—who just co-curated the Bronx Biennial.

Our work is not about the individual. It’s about collaboration and building.

How do you know when you’ve found the right people?

CV: I pride myself on reading energy well. I feel like I knew immediately, with Jack, that it was going to be a fruitful partnership and friendship.

JR: And I think a lot of the artists we work with, we’ve met through other artists.

Installing Mariana Parisca: Corriente at Más Allá, Bogotá, Colombia, 2022. Left to right: Jack Radley, Mariana Paricsa, Constanza Valenzuela, Rafael Díaz, Maite Ibarreche. Photo: Sofia Blanco.

CV: But you never know until you hang out with them. You literally just hang out. Mariana [Parisca], for example—who we just did a show with in Colombia—Jack has known her for years, and when we did a studio visit I clicked with her immediately. So she participated in our show [Transient Grounds] at Governors’ Island.

JR: She packed all the work in her car and she showed up on the island. Everything fit perfectly to a tee. She’s on top of her shit. She’s her own registrar, her own fabricator — she’s everything. Then this opportunity came up in Colombia. We didn’t have the money to fund more than a checked bag, but we knew we could trust Mariana to do an amazing show of work that could fit in her suitcase. So she disassembled all these works, and again things fit perfectly. We get to the gallery and—

CV: —we all assemble together, with zero drama. Mariana was the perfect person to go on the trip with and do the show with. We wouldn’t have done the show, or even proposed the idea, if we didn’t know the perfect person to do it with.

JR: We’re not just conceptualizing these projects; we’re holding the tires in place and drilling. You’ve got to want to be on the ground with the people making the work.

Installation view: Transient Grounds, 2021, Governors Island, NY. Photo: Daniel Terna.

When do you consider a show a success?

CV: We were just talking about how the stakes are getting a little higher as our work is getting more visible. But I think our work is successful when everyone has fun and the artists are happy.

JR: When our collaborators feel like they’re pushing their practices, and when we introduce good people to good people, we’ve succeeded.

Constanza Valenzuela and Jack Radley (ACOMPI) Recommend:

20 Artists to Watch:

-

Basie Allen

-

Noel W Anderson

-

Daniel Barragán

-

Juan Caicedo

-

Karla Ekatherine Canseco

-

Yuchen Chang

-

Vincent CY Chen

-

Florencia Escudero

-

Stfeano Espinoza Galarza

-

Edgar Allan GoPro

-

Craig Jun Li

-

Amanda Martinez

-

Mariana Parisca

-

Xinan Helen Ran

-

Sofia Reyes

-

Bassem Saad

-

Edward Salas

-

Cameron Spratley

-

Daesup Song

-

Sandy Williams IV

- Name

- ACOMPI (Constanza Valenzuela and Jack Radley)

- Vocation

- curators

Some Things

Pagination