On fetishizing your own process

Prelude

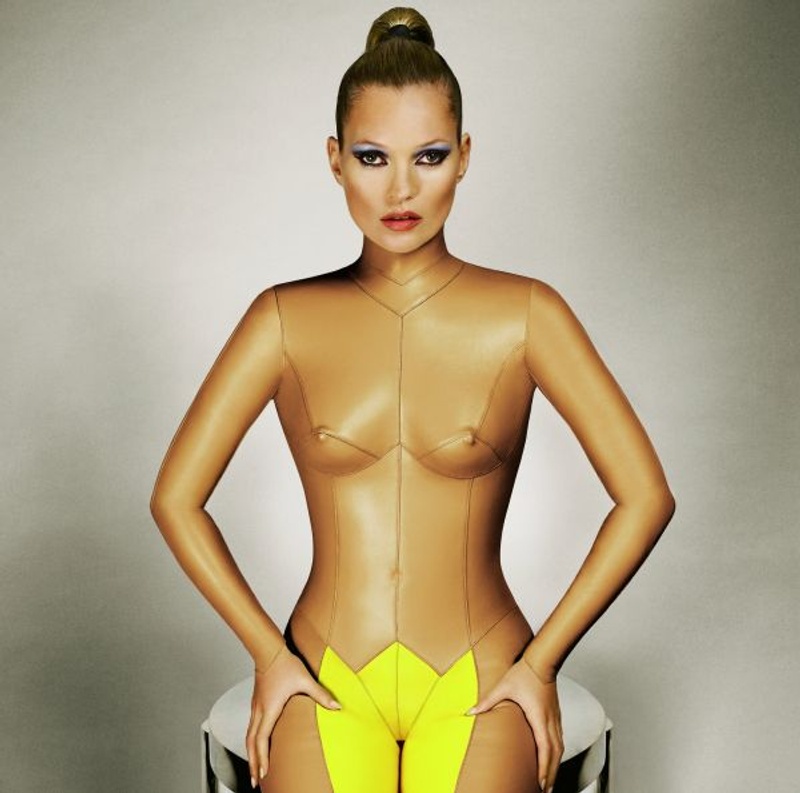

Established in 1988, Whitaker Malem are a creative and personal partnership between Patrick Whitaker and Keir Malem. Having produced their own collections of sculptural leather garments, the duo went on to create catwalk pieces for designers including Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan. In 1995 they established a technique for the sculpting and leather covering of torsos/bodies-which they subsequently developed. For 20 years Patrick and Keir have collaborated with artist Allen Jones creating leather-covered sculpture using this technique. Whitaker Malem have worked extensively in the film industry for over 15 years creating principal costumes for movies including Die Another Day, Eragon, The Dark Knight, Captain America: First Avenger, 300: Rise of an Empire, Wonder Woman, and Aquaman. Based on Patrick and Keir’s accumulated experience in art, fashion, and film, their current works explore sexuality, the sexed body, and gender identity.

Conversation

On fetishizing your own process

Designer artisans Whitaker Malem on making sure you're properly credited for your work, appreciating the value of true craftsmanship, and what makes a long-term partnership work.

As told to Ambrose Mary Gallagher, 3198 words.

Tags: Fashion, Design, Inspiration, Process, Beginnings, Collaboration, Business.

Patrick: You’ve got Patrick Whitaker here, and Keir Malem is also present, he’s in the studio here. This is Keir. Say hi.

Keir: Hello there.

Patrick: So, you know, he may interrupt, but I tend to do most of the talking. But at least he can take part, too.

Perfect! So, you’re in this niche area of the fashion and film world. How did you find that spot for yourself?

Patrick: Well, I did a degree in fashion design at Saint Martins and graduated in 1987. I had studied footwear at college prior to that. I first got introduced to leather really when I was about 15, and I’ve been sewing leather since then. Keir helped me with my degree show at Saint Martins in 1987. We had molded leather pieces in that collection. So, that’s how it got started… We did our own label and our own thing for about 10 years, and then we moved to film because we were approached by the costume designer for a Bond movie that we worked on. That’s what got us into the film business…

So we did 10 years of our own label, then we did 10 years of working with other people, then we did 10 years in film, and now we’ve come back to doing our own thing again. The constant through that, and probably the most important thing for us, is that we’ve been associated with and have worked on many pieces with Allen Jones, the pop artist, for over 20 years. He’s had an enormous impact on our credibility in what we do.

Photo: Whitaker Malem

Can you talk more about the impact of having those overlapping interests—fine art, fashion, film? How do those impact each other?

Patrick: It’s interesting because many times we’ve been to meetings on movies, where they have our higher fashion pieces from magazines and stuff from over the years up as inspiration or mood boards… and then we’ve been to local fashion meetings where the film stuff is the inspiration. They are quite symbiotic. The film stuff has become harder for us to operate in… It’s very important to us now, after over 30 years of doing what we do, to be credited correctly, and it’s become harder and harder in the film industry to receive correct, specific credit for what we’ve provided.

What do you feel is the appropriate way to give credit?

Patrick: The trouble is that if you go on contract to a movie, they just want you credited as individuals, i.e. Patrick Whitaker and Keir Malem. And they could easily just tamp us down under a blanket of leather workers or something like that. And that’s sort of fair enough, but we’re not very happy about it because they do rely on our technique so heavily. I know many people who are very grateful for the work and very happy to beaver away and do it without that kind of acknowledgement, but it’s not acceptable to us any longer.

Then again, we have to appreciate and respect, which we do, the fact that if you are required to create a bat suit, that it’s nobody’s design because someone drew it in 1932. It’s been through god knows how many iterations, and everyone has a say on—you’ve got a director’s input, you’ve got Christian Bale, in our case, his input, and you’ve then got the costume designer’s input. And then, you know, we’re below all that. So you have to understand where you are in this famous pyramid, which is so beloved in the film industry.

How do you do that kind of collaboration when you’re dealing with input from so many people, and input even from people as far back as the ‘30s, who all have a voice?

Patrick: Well, it’s tricky. I mean, you’ve got to try and please everyone, and you have to accept that it is, to a degree, design by committee. The reason that we’ve been more associated with Warners and DC than Marvel is that Warners/DC do not have in-house staff drawing characters day in, day out. When a costume designer turns up on a Marvel shoot these days, he or she is passed a pile of drawings by Marvel and required to lift them off the page, via people like me and Keir. So, it is all theirs and therefore, they’ve got exactly what they want, and they know what they’re doing generally. But obviously, if you’re a creative person, which we are, it may not be particularly rewarding. And we’ve had better opportunity with some other studios than others in helping to realize these things.

Givenchy

Also…We all suffer from living in a world that’s supplied, sadly, by a culture of t-shirts costing a couple of bucks and being virtually disposable, which is disgusting. People just seem to think that these things get made by a big robot machine where a roll of cloth is fed in one end and either suits or dresses or t-shirts come out the other. And the reality is that nearly all garment manufacturing is entirely hand done, and requires sewing and hand skills. And I think people suffer from that thinking when it comes to costumes as well. Of course, in movies, time’s always tight, and when they want very exotic or unusual things, the one thing that they don’t really understand is that you can’t buy time. And they’ll always come up against that in the end, just because they have this preconception that it’s just clothing.

Keir’s saying that what we always find out—especially with these superhero shows or the fantasy shows—is that basically what you’re creating at the end of the day is workwear for stuntmen. There isn’t a costume we’ve made that hasn’t ended up flying around on wires or without someone getting blown up in it, or soaking wet—because that’s what these shows are like. So there is that side of it.

Our technique is almost like a shoe for the body, which is especially the case with the molded leather pieces that we make. We principally make a sculpture or a block for every single costume or piece. We don’t just make the garment, we make the dummy or stand that the garment has been made on. And I think that’s what differentiates us from other people who do these processes.

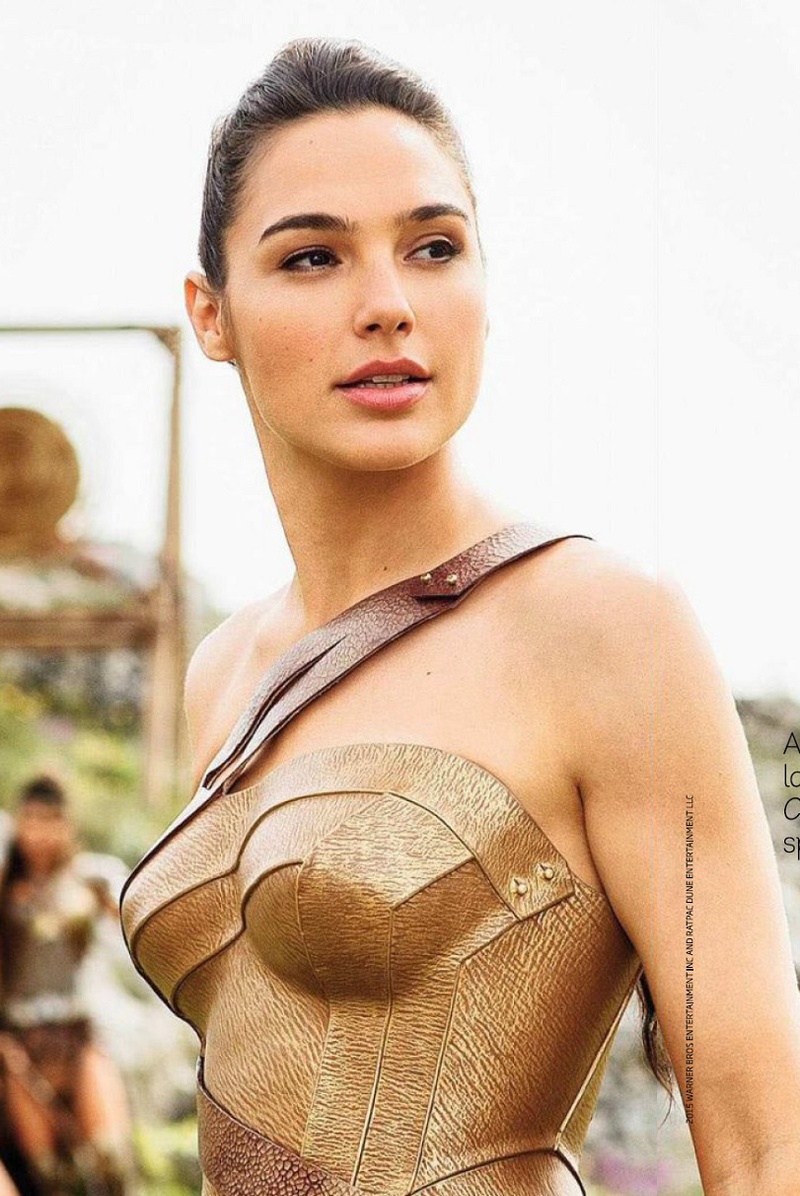

Wonder Woman, Warner Bros

How did you develop that technique?

Patrick: My mother was a sculptor, and we understand a lot about casting fiberglass and mold-making. I’ve always been aware of these processes. My brother taught me ceramics at school, because he’s a good deal older than me, so there’s quite an interest in three-dimensional and sculptural techniques in my family. We started making our own mannequins and stands way back, and then, fortunately, technology caught up with us, and the film industry in particular has provided very interesting opportunities for us to expand our knowledge and experience with this, because of laser scanning and 3D-milling processes.

You collaborate with a lot of film industry people, or with Allen Jones and other fine artists, but what’s it like collaborating and partnering with each other for so long? How do you maintain something like that?

Patrick: It’s an odd situation because we’re in a relationship as well. We’re a personal and business partnership, and we’ve been that for 33 years. We live together and work together… It’s still not that easy, and you don’t always get on. But we do have strengths that we play to. Keir cuts everything we make, in terms of physically cutting. That’s exactly what he’s doing right now. And I sew everything that we make. And the sculpting process I’m more involved with. But we discuss and we negotiate everything we do with each other, because that’s how we work. We couldn’t have done it without each other, and it wouldn’t have happened the way it has. And we do work with large teams of assistants. For instance, on Wonder Woman, we made 160 costumes, which took us a year. And we had up to 20 people helping us, at the film studios, to create that. But generally, quite often it’s just the two of us. And I guess you just get on with it.

Like you were saying, it’s taken a while to build up this base of different kinds of work. How did you figure out how to make a living through your creative work? I imagine it wasn’t right off the bat.

Patrick: We both had part-time jobs for a long time before we settled down into just being Whitaker Malem. We had a good break. The college that I graduated from was very prestigious in its day. We were fortunate enough that I had to take a part-time job at the main youth fashion department at Harrods department store in London. When I graduated I took a job there, and then we managed to get them to stock some of our pieces. At the time, there was a very famous boy band getting going, called Bros. They came in and bought our jackets, and then we started doing their stage wear.

Photo: Allen Jones

Then there was a very nice shop in Knightsbridge that sold Galliano early on—and through them, we got wonderful, wonderful pages in UK Vogue, shot by Herb Ritts, who was a legendary photographer of his day. So, we were very, very lucky. We got wonderful, wonderful, impactful, high-end press of our pieces very early on. However, and this is an interesting point, that didn’t translate into sales. You would have thought, since we had these pieces in the stores in London, a page of them in English Vogue, a superb page—and then we still wouldn’t sell one.

So, really, our bread and butter has always come through commissioned work, and people who identify our skills and say, “We’re thinking of doing this, we’d like something like that.” We never particularly made a ton of stuff and then just sold it in stores. We don’t operate like that—in a way, that’s how we should operate, that’s like a proper business, but it just has never worked like that for us. So we really go from one commission project to another, and in the meantime, we make our own pieces, which we’ve been doing a lot more in the last few years. We were so dominated by the film business for so long that we stopped doing that, and we’re very happy to have returned to our own work, with a new vigor and more information and better techniques.

What kind of tips do you have for advocating for yourselves as artists? Especially in the context of big projects that might try to dilute your impact.

The main advice I would give to people is really, if you’re any good at anything, stick at it. And if you’re in love with what you do, stick at it. People are becoming more and more entranced by actual craft—hand making and process—which is what we’re into. We literally take leather, dye it, cut it, sew it, gild it, put a texture on it, and then make the things. Everything’s built from the ground up. When we started, that wasn’t cool, and it should all be techy, and kind of 3D printed, and god knows what. But I think more and more, people are realizing the value of this. I mean, on an artistic note, we have fetishized our own process to a very high degree. We require such high standards for what we do that the objects are fetishized both in their realization and in their making.

It hurts not at all to have had some experience of retail or people reselling stuff. Don’t be afraid of being good with business. The main thing is to be fair and not greedy—that’s my business advice to anyone starting out. It really is. I can’t believe that we’ve done as well as we have out of doing what we do. But when people get us, they really get us. And that’s what I said to Christian Louboutin, when he came to see us a year ago, and we were discussing potentially collaborating with him. I said, “Christian, when you’ve got us, you’ve got us 100 percent.” Because the one thing I cannot bear, and the one thing that we always try to avoid, is doing things in what we refer to as a “half-baked” fashion. I absolutely deplore anything that’s half-baked. If you do it, you do it properly, or you don’t fricking do it.

Photo: Ram Shergil

You mentioned a few minutes ago how you fetishize your own process and not just the product, but also the process. Can you say more about that?

A lot of the pieces we create are really, really difficult to make. In some cases they’re getting harder to make, because your eyesight’s going, and this and that and the other. But the point is that we do, in a way, make them hard to make for ourselves. But that makes them look all the more unreal and unbelievable when people see them in person, because the work is very, very detailed, and hopefully it’s exquisitely realized.

All the leather comes to us in wonderful skin color, because it’s rawhide, veg tan. And the handling of that, even in the studio, is very tricky because you can get grease on it under the machine. You only need to touch your nose and then touch the leather, there’ll be a mark on it. It’s all absolutely like that, very pure. It is then wet molded, and then we wax it, and then basically, that kind of seals it. Not permanently, but it makes it touchable. So the materials are hard to handle, and the stitching is very tricky. It’s a masochistic process.

Another point I want to make, especially to young people coming new to these kinds of processes, is that people must appreciate that nothing really, really beautiful was ever very easy to make. I mean, yes you’ve got a wonderful gestural Jackson Pollock painting, or something like that, there is some magic in that. But when it comes to true art-and-craft processes, or something being truly exquisite, or something where people are going, “My god, how have they done that,” it’s because it’s fucking hard to do. It’s always going to be that way. To make beautiful things is not easy.

That comes back to what you were saying about how you never want to make anything that feels half-baked or half-done.

Absolutely. Absolutely… I do understand, especially these days, people wanting to be known for doing something amazing and/or beautiful, but I don’t think very often people realize what they’ve got to go through to achieve that, whether it’s being an extraordinary and unusual performer onstage, or whether it is producing a piece of clothing, or an amazing shoe, or a piece of exquisite jewelry. I mean, I encountered some absolutely amazing jewelry at a Rick Owens exhibition of his furniture, recently in London. There was a woman there wearing this necklace, and I’d never seen anything like it. It was a DNA spiral made out of hexagons of the finest gold wire, hand-worked into perfect, faceted shapes. She tried to tell me that it was her design, and she had commissioned it. But then she admitted she wasn’t the maker. The skill was not hers. She may have had the idea, but the actual skill, the actual genius to handle material, the ability, was not in her hands. If I had wanted to buy a piece, I’d go to the maker, not her.

I think that there are a lot of people, especially starting out, who want to be the big idea person. You want to have this finished product.

I know. And I tell you what, Americans are the number one asset. You guys have the worldwide number one gilded cocks for it, I’m sorry to say.

And what we feel very strongly about now is that the makers, and the talent behind these people, has become too obscured. And this is what things like Instagram and the internet are doing, they’re just outing them all now. They’re outing them, you know, because it’s gone on for too long.

But then again, you know, I need Louboutin’s commission for leather life-size sculptures, which we’ve created from scratch, for him. You know, because I’m not going to go and fund that and make my exhibition and do it myself. But the nice thing is that he can credit us entirely.

So if you’re a middleman, then make sure that you are crediting and compensating the makers.

Yeah. Yeah.

There’s a role for that.

You have to have a certain amount of fat on your back, as you call it, or cash in the bank, to have the ability to go, “Actually, look, this is the deal, take it or leave it. If you don’t want this deal as I’m presenting it, then I’m not doing it.” You’ve got to have a certain amount of backup to do that. There have been many a day when we’ve gone, “We’re doing it because we need the money.” So I’m not standing on my high horse too much, you know. But I very much want to support the gifted makers and people doing it, because it’s massively important.

Photo: Pierre et Gilles

Whitaker Malem Recommends:

Patrick recommends:

Peau d’Ane — (aka: Donkey Skin) 1970, a magical Jacques Demy film.

Lynn Chadwick — amazing British figurative sculptor (1914-2003)

Score – hot and interesting 1974 Radley Metzger film.

Michel Legrand – wonderfully melodic film music composer with over 200 film/tv scores.

Duggie Fields — Artist, maker of fabulous paintings, and friend.

Keir recommends:

Dune — Frank Herbert’s 1965 book offers a unique comprehension of ecology, politics, human potential, and connectedness—combined in a great story.

Satyricon — 1969 Federico Fellini film takes you on the most artful of journeys, truly a delightful feast for the eyes and mind.

“The Garden of Earthly Delights” — Hieronymus Bosch c.1500, whenever I encounter this image I have to engage with its voyeuristic, psychedelic, surreal eroticism—there is always something new to be found.

Dancing — A primitive pleasure, warm up, overcome self-consciousness, connect with music.

Lying on a quiet beach — late afternoon on the beach with the sun and wind caressing your body and the sound of waves lulling you away.

- Name

- Whitaker Malem

- Vocation

- Designer Artisans

Some Things

Pagination