On embracing boredom as a creative force

Prelude

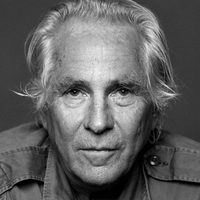

Danielle Clough started her career as a photographer, designer, and VJ after studying art direction and graphic design at Red and Yellow School of Advertising, all the while stitching as a hobby. Her hobby turned into her vocation when her work was featured on This is Colossal in 2016. The piece led her to quit her jobs as a waitress, designer, and photo taker and opened up the door for her to work with Adobe, Gucci, Nike, The United Nations, and others while exhibiting and teaching internationally. She currently swims, sews, and teaches in Cape Town.

Conversation

On embracing boredom as a creative force

Embroiderer Danielle Clough on turning crafts into a career, utilizing pop culture for artistic purposes, and working outside of the outdated gallery system.

As told to Lior Phillips, 2800 words.

Tags: Art, Craft, Inspiration, Beginnings, Process.

How do you know when a project will balance your passion, time management, and bring in income?

It’s a gut process. I’ve done practical things, built up practical systems, focused on things that people like, that I enjoy making, and that are easy—like [embroidering on] tennis rackets. I have this financial security around that. People seem to really like the rackets, and they take some time, but I can make them and then I can sell them. So, I don’t feel this hunger to take on work that I don’t necessarily want to take on. So, when it comes to the stuff outside of just making money, the work that I love, either it’s challenging, something that I haven’t done before or on a material that I haven’t done, or I’m doing a commission, or something like that. Sometimes I’ll take on commissions just because the emails feel right. I did a project for an organization for people with macular degeneration. These are mainly older people with very, very bad eyesight. In the waiting room [of this organization], they created these magazines with huge text. They asked me if I would do a portrait for that. I love doing portraiture, and it’s for something that’s really sweet and very cool and it has goodness in it. For me, it’s the intention in which I do the work. You always protect the intention.

How does your creative process shift from your renowned embroidered rackets compared to those portraits?

It’s the same all round. The intention is always to get better. So, maybe the problem solving element of the creative process isn’t there. If I’m doing something on fishing nets that I haven’t done before, then I have to engage in the tools and tinkering, trying to figure out new ways to do stuff, which is actually the most exciting part of the creative process. But then in the actual creating or making of something, the goal is always to be better, and that’s [always] the same.

Prior to embroidery, you started out as a VJ. When was that moment where you decided to focus entirely on embroidery as an artist?

When I was at school, I would make plush toys, because I had studied fashion design very briefly. I dropped out after two weeks. But I knew how to sew, and I’d make these plush toys and sew the details on. Once I just doodled a rabbit, and I thought I had invented embroidery. I was like, “Oh my God, thread sketching! No one has thought of this!”

In 2015, I was a VJ [then] and doing some embroidery work [at the same time]. I applied for [annual art festival] Design Indaba, and they had a very successful market with lots of embroiderers. At first I thought that I was going to start collecting and do some workshops with people, but then I started working on rackets.

What drew you to using something action-oriented like a tennis racket for something still and contemplative like embroidery?

I wish it was my own moment of genius, but it definitely wasn’t. A friend showed me this woven heart someone had put on Pinterest, and it was this whole, “I can do that, but do it better” thing. I’m highly competitive, mainly with myself, but also with other people. I don’t let anybody around me know that I’m subtly going, “I’m going to beat that.”

So then I went to Milnerton Market [in Cape Town] and I bought a racket, and did one with that same approach. And then the next one was better, and the next one was better, and then I evolved the technique in which I can create any shape within it. I built a website with a few of the embroidery rackets that I had done, and then those went viral. Within three months, I was a full-time embroiderer just because of the demand.

Were you already thinking of how to sustain it business-wise? Or were you just focused on the art and the craft of it?

I knew I loved it. I knew that it was something I wanted to do. I would sit and watch TV, and I would sew. It was the thing that I did between all the other things that I had to do. And then I would put it on Facebook, and somebody would be like, “Can I buy that?” And I’m like, “Really? Okay, cool.”

I’ve always shared my stuff quite naturally on the internet. Even when I was taking photographs or drawing, I would always just put it out into the world. I’ve never had that feeling that this is mine and no one will like it. I’ve always thought of sharing as being the last part of the process.

Opening yourself up on a platform like Instagram or Twitter naturally exposes you to two-way communication with DMs and comments. How do you balance the concepts of accessibility with an audience while also having some privacy or mystery around your work and your process?

Any relationship that you have comes with learning, whether it’s with a person, or your work, or food, or your audience. Sometimes you overeat or sometimes you overshare, and then you don’t feel great afterwards. You find your balance and your boundaries within that. I have recently come to a point where there are things in my process that I hold back. If somebody sends me a message and says, “How do you do this and this,” I’d rather push them to something that I’ve already created in a way that has my ethos in it. Putting people through those channels and giving yourself that space conserves your own personal energy. I’m super grateful for the communication and the connections that I have with people that I’ve never met. But those relationships always need boundaries. You are naturally going to have your own style and your own voice. Everybody has their own taste in colors, in formats, and what interests them. It’s about building the confidence to access that, and to then explore it and to play within that.

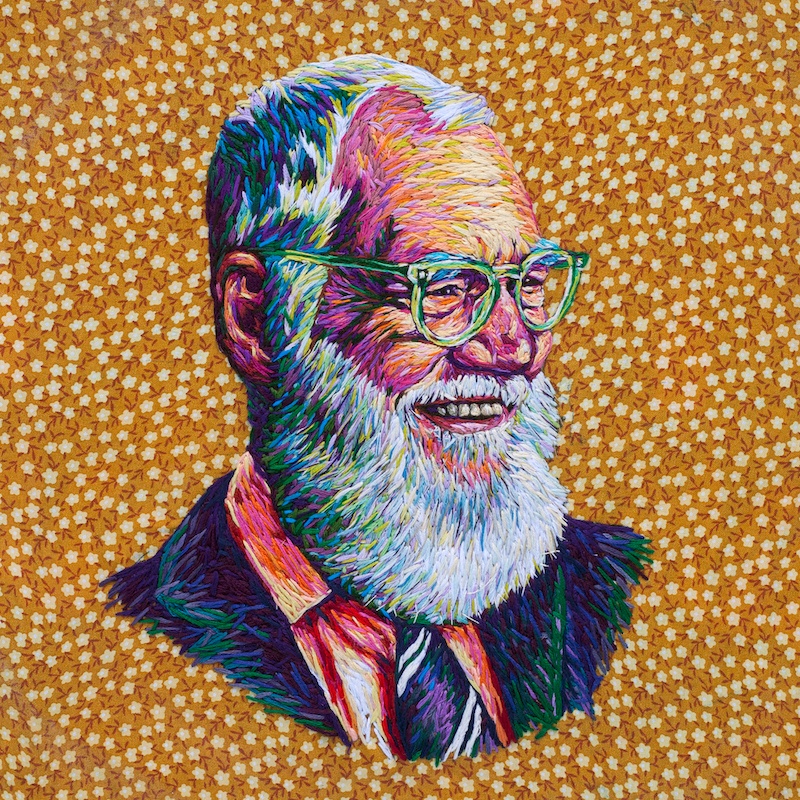

When you’re commissioned for a piece for, say, David Letterman, you’re getting into a sphere where you are working with people that you respect. How does that kind of recognition affect you as an artist?

Well, it’s always very amazing at first, and then quite overwhelming. And then obviously the process of making [that piece] is a lot harder because if I’m making work only for myself, I know when it’s done. But sometimes the eyes that are going to see [the work] are somebody else’s, somebody you respect or someone from a brand or an agency, and then you’re a lot more critical of the work that you create and there’s a lot more anxiety around it. But once it’s out, there’s always a back and forth. There’s communication within the process.

As an artist, what is the most important thing that you felt you needed when it came to getting involved with big brands and corporations? How does the differentiating line between ‘art’ and ‘craft’ play into that mentality?

I studied advertising and graphic design, so I come from a very commercial background. I’ve worked as a designer and as a photographer, and all of that is very much about client relationships. Your job is purely to take somebody’s vision and create it so that it’s visual. With embroidery, it was this hobby, this thing I did on the side. Also, it straddles the line of arts and crafts. I’ve never really pegged myself into the artist category. I see myself very much as a commercial creator. The best tool that I’ve had when working with those big brands is having experience with different aspects of the creative process.

The process that you are now so known for is something that many people consider a craft that feels very accessible. Do you feel like you sit on the same plane as artists, say, working with a paintbrush and a canvas?

I don’t think so. I’ve built my business and my systems all independently because my medium is a craft. I sit very much outside of the traditional art world and so does my medium, and I absolutely love that. I love the autonomy that comes with it.

I think the gallery systems are outdated. The art world is very judgmental and quite highfalutin. It’s about the collectors, and people determining your price, and people deciding what’s good enough to go out on the walls. That dictates your content. I just don’t want any of that. I want to wake up, and if I feel like embroidering a toucan on a piece of pink Hessian, I want to do that. I don’t want to have to go through the process of thinking about everybody else and how that’s going to be perceived. I want to be able to feed into the most pure, comfortable, creative thing inside myself. Working outside of the gallery systems, but also working within the craft world, gives me so much space to remove the expectations that come with being an artist. I love being a crafter, because a crafter doesn’t have to say anything, they just have to make something. That gives me a lot of room to just create without having to have this backstory, or this meaning, or this integrity in the work.

It’s also made me think a lot about this idea that crafting is women’s work. It’s catering into the idea that craft isn’t good enough. And that’s bullshit. The way we value craft is the problem, not the fact that I’m called a crafter. I love that embroidery is seen as a craft. We’ve put art on a pedestal. The fact that it’s supposed to mean something higher than ourselves is boring.

That’s clear in the way pop culture plays into your work in a style that’s both playful and respectful.

There’s humor in it, for the most part! Most of the stuff that I’m drawn to, even if it’s Wednesday Addams, who’s obviously quite a dark character, there’s humor in this embroidered version of her. But it comes from respect, not taking the piss. A lot of this stuff that I enjoy, there’s a playfulness that excites me about it and draws me in. The first pop reference image I ever did might’ve been Steve Zissou. You watch something and you are so drawn to that persona, and then just want to indulge in it a little bit. So if I put on The Big Lebowski, I’ll try and watch it while I’m sewing so that I get the person and that moment in the piece. It’s a sound thing and it’s a color thing, and then it becomes tactile, and then you have it in front of you.

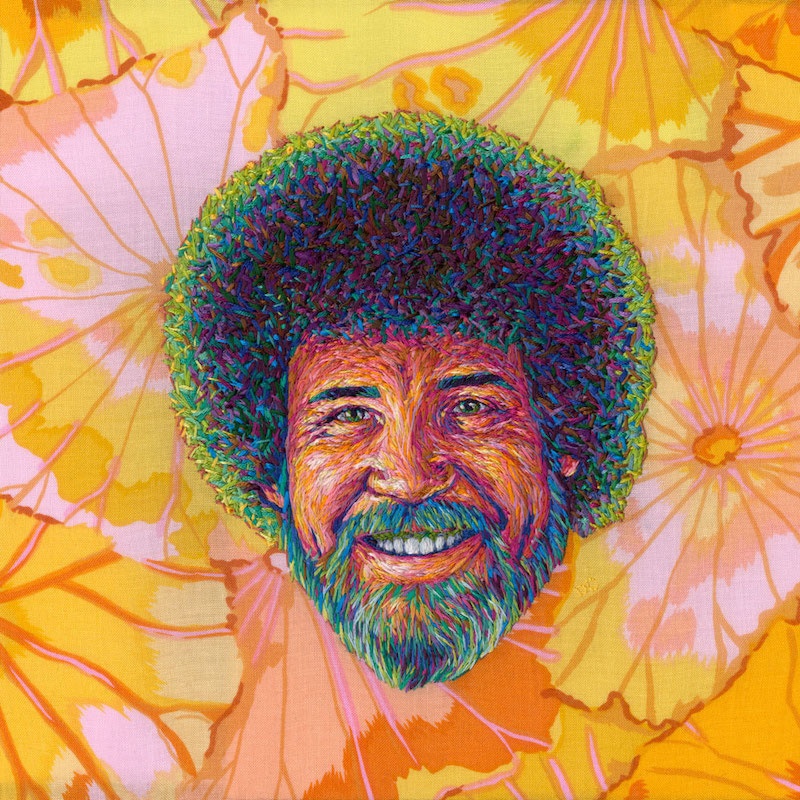

We like connecting with each other on these mutual experiences. I recently did the portrait of Bob Ross, and it’s amazing how people feel about him. They just love him. Bob is the nicest person in the whole world. We do not deserve Bob. People tell me stories of how they used to watch Bob, like this woman whose husband is quite ill, and he’s a painter. They watch Bob Ross at night and drink wine to relax. It’s such a beautiful thing for somebody to share with me, and it becomes this amazing connective line. I don’t necessarily create the first points of connection, I just get to be a part of this narrative.

When you’re working in a specific physical limitation, whether that’s on a hoop or on a tennis racket, how does that boundary affect your creative process?

Well, the main thing is, actually, that I can’t go further than my arms or they make trouble. I only have two arms, so they just need to get stretched out longer, or [I need to] get some super power. [Laughs] I always choose my subject matter based on the limitations of the surface. That’s problem solving. But I think the main limitation that I’m feeling at the moment is my inability to manage my time, because that’s actually my greatest resource. Doing something very detailed on a very difficult surface, all of that stuff can be conquered with time.

What does managing time properly look like?

It looks like not being on your phone. [Laughs] Just step away from the things that you lean on, things that distract you. Essentially, step away from your comfort to create enough space that you can be bored. The best creations and the best things come out of boredom, but we don’t allow ourselves to be bored at all anymore. We often put ourselves into these little distraction suckholes, this abyss of distraction. But in that quiet of actually not knowing what to do with yourself, that’s when I start pulling things out of the cupboard and start tinkering.

Aside from money, what are the rewards of your creative practice? What do you get out of this work and what has it taught you about yourself?

Connection. The work that I create has a lot of nostalgia tied into it. The actual medium is nostalgic. Most people are like, “That’s granny work. It’s weird. It’s creepy old lady work.” Most people have seen their parents or their grandmother do it, or it’s on doilies and on handkerchiefs and stuff like that. It feels quite outdated, but there’s something nostalgic about it. And then the content is nostalgic. So, the connection that I’ve created through it, through the workshops, through the online classes, through what the work means to people, and obviously what it means to me, is the best part of what I do, hands down.

At the same time, people can then create their own story about your work. It has a whole different life after you’ve made it.

Yes! Once you’ve created something and put it in the world, it’s the end of your relationship with the piece, and the beginning of its relationship with everyone else. And it’s actually not your business what people think about your work. You can’t expect people to see anything through your own eyes. You can suggest to people what your work means, but that’s not what it’s going to live as. They like it or they don’t, and it means something or it doesn’t. It’s not actually personal. You don’t know if it’s going to end up in the MoMA or it’s going to end up at some car boot market. That’s not up to you anymore. You can be precious about the work, but you can’t be precious about the way that the work is perceived. There is this massive world with a million different versions of comfort and of truth, and part of the problem that we’re sitting with now is that we’re all trying to fit everybody into one box. You have to listen to your audience, but you can’t cater to your audience, because then you’re going to be making somebody else’s work.

Danielle Clough Recommends:

Colour: Travels Trough the Paintbox is an amazing book about the history of colors by Victoria Finlay. It’s incredible to have a deeper understanding and appreciation for something that we are surrounded by constantly—the history behind something as simple as a pencil with its famous graphite smuggler Black Sal during the ‘pencil wars’ or the espionage missions for the well kept secret of carmine, a rich red made from pregnant cochineal beetles. This can still be found in some foods.

No Such Thing as a Fish is a podcast by the makers of QI. It’s a show packed with wild, miscellaneous facts, and I’m a firm believer that you should go to a date—even with a friend—armed with facts. Facts > gossip.

Take out a puzzle and leave it on a table to chip away at.

Practice gratitude. It’s my experience that it is the foundation of happiness and contentment (which is something that will ebb and flow). Treat it like a skill that needs practice and to be consciously harnessed. Although some days are easier than others, I highly recommend counting those lucky stars.

Listen to the Bongeziwe Mabandla album iimini.

- Name

- Danielle Clough

- Vocation

- Embroiderer, Artist

Some Things

Pagination