On following your instincts

Prelude

Ian “Swifty” Swift is a London-based graphic artist. Swifty first got the taste for graphic arts at The Face magazine in 1986. Using his signature “remix” visual style, he’s created countless iconic designs and logotypes for the music industry and youth culture via publications like Straight No Chaser and labels like Mo’ Wax. In 1997 he launched Typomatic, the UK’s first independent Font foundry. When Swifty shifted his focus towards art, he produced a body of work making use of nostalgia and camo. He more recently released a 374-page book, The Graphic Art of Ian Swift, chronicling his decades of graphic making.

Conversation

On following your instincts

Graphic designer and artist Ian Swift on how he got started as a designer, letting your interests and instincts guide your work, and always believing that you are, indeed, the greatest.

As told to Ken Tan, 2116 words.

Tags: Design, Process, Beginnings, Mentorship, First attempts, Inspiration.

Can you tell me about how you started at The Face magazine?

Neville Brody, who revolutionized magazine design at that time, came to Manchester Polytechnic to do a talk. My tutor knew him. I would have been 21. After the talk, Brody started looking at portfolios in alphabetical order—I would be second to last. I knew damn well that he’d had to wade his way through a lot of shit before me, so I walked through the door with my portfolio, and said something to the effect of, “I bet you’re really hacked off at having to look through all that shit.” Like, really cocky. It worked. He immediately sat up in his seat and looked me in the eye. I had him. Because of my prior work experience I had loads of hand-drawn typography in my portfolio, which resonated with Brody. I mean, it’s one of those fairy tale stories where the guy pulls out his pen, writes his number down on a bit of paper, and says, “call me.”

So did you call?

I started calling him the week after. Every day. Bang, bang, bang. I got to know his assistant Dave very well because Brody was always in a meeting. I just persisted. I’d phone in the morning, I’d phone at lunchtime. Then I’d nearly given up and I thought, “Ah, he’s just bullshitting me.” My last try was at seven o’clock on a Friday evening, Brody finally answered.

That was it. Next thing I knew, a week later I was on the train to London to meet Nick Logan. Logan liked my portfolio, so literally the day after I had put up my degree show, I left Manchester with a rucksack full of clothes and 20 quid in my pocket. That was it. I never went back.

What was your role at The Face?

My role was a junior designer. I had to learn quickly—within the space of 24 hours I was designing layouts.

You came straight from school in Manchester. How did you adjust? How did you get accepted?

By being myself, I suppose. The style that I had in those days was a flattop haircut, checked shirt, Levi’s 501 jeans, Dr. Martens. The vibe was a kind of rockabilly. I fit in, in a funny kind of way, because I was Northern. Back then it’s normal for the South to take the piss out of the North. I embraced that, and it didn’t take too long before everyone loved me. Also I’m one of those people that kept my head down and got on with whatever. Be nice. Say please and thank you.

That’s practical. What was it like working with the legendary Neville Brody?

I only actually worked on The Face with Neville for a couple of issues, which was fantastic for me. That was the reason I was there: to work underneath the master designer, Neville Brody. The deal Brody had with Nick Logan was that he was going to leave to set up his own studio. Soon Robin Derrick took over. He was much more into styling, art direction, and fashion, and less into typography and page layout. I learned about working with images. You know, when Nick Knight or Juergen Teller came with their photographs, we’d lay them all out on the table to work them into a spread. It’s all about the flow of the magazine.

How did you move to work on Straight No Chaser magazine?

By the time Nick Logan had started Arena magazine, I had finished at The Face. I’m designing Arena magazine while working for Brody, who had moved to the East. That’s where I meet Paul Bradshaw of Straight No Chaser. It was 1989. Neil Spencer, ex-NME editor, who was good mates with Paul Bradshaw, came up to Brody’s studio one day with a copy of Straight No Chaser. They were looking for a full-time designer. Spencer wanted Brody, but of course, got turned down. Brody was just too busy to take on a pro-bono. That’s where I came in. It helped that I had my own Apple Macintosh. Most magazines were produced on Apple Macintosh then, so when I got paid £1,500 for a little freelance job for Publicis, the first thing I did was to buy a Macintosh.

Why not celebrate with £1,500, instead of the Mac?

On holiday? Yeah. Well, because I knew that the Mac was the way forward. You had to have this little machine, you know. I didn’t even think about it, it was a no-brainer, the minute I could afford to buy a little machine, I did. It doesn’t work anymore, but I’ve kept it all these years in the loft.

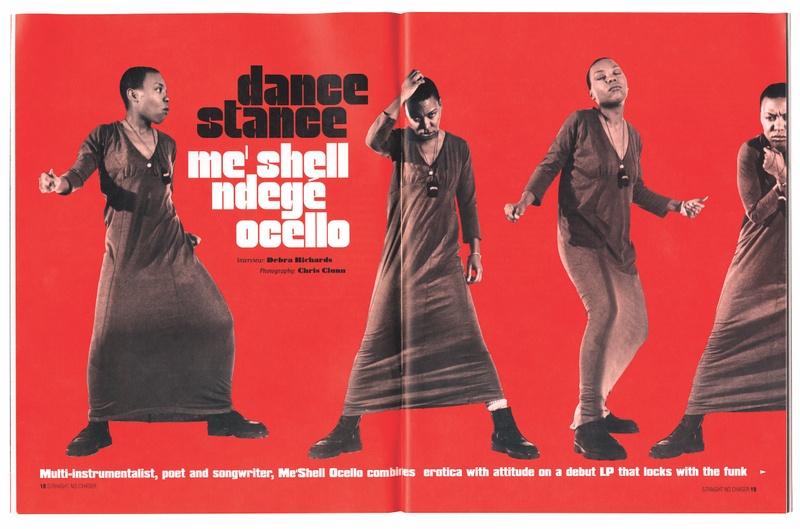

To me, Straight No Chaser was where Swifty became Swifty. You gave music an identity. How did you find the right typography, the right kind of look and feel for each job?

Don’t forget I had Paul Bradshaw, the world’s number one aficionado of Black music, guiding me. Within the space of a few weeks of working on Straight No Chaser, I’m going to the clubs absorbing the music, hitting the record shops just to look at all the record covers on the walls. I’m in the DJ box digging through Gilles Peterson’s records looking for design inspiration. I’m looking at the sleeve designs of Blue Note Records…

Yes, exactly, Reid Miles’ designs for Blue Note Records. You know, there were no Blue Note design books then. There was no internet. For your visual inspiration, you had to go out and find it. I do remember rifling through Gilles’ box while he was DJing, and he’s having to nudge me out of the way. “Swifty, get the fuck out of here, I’m DJing!” He probably thinks I’m looking at what’s he playing. No, I’m looking at the record covers.

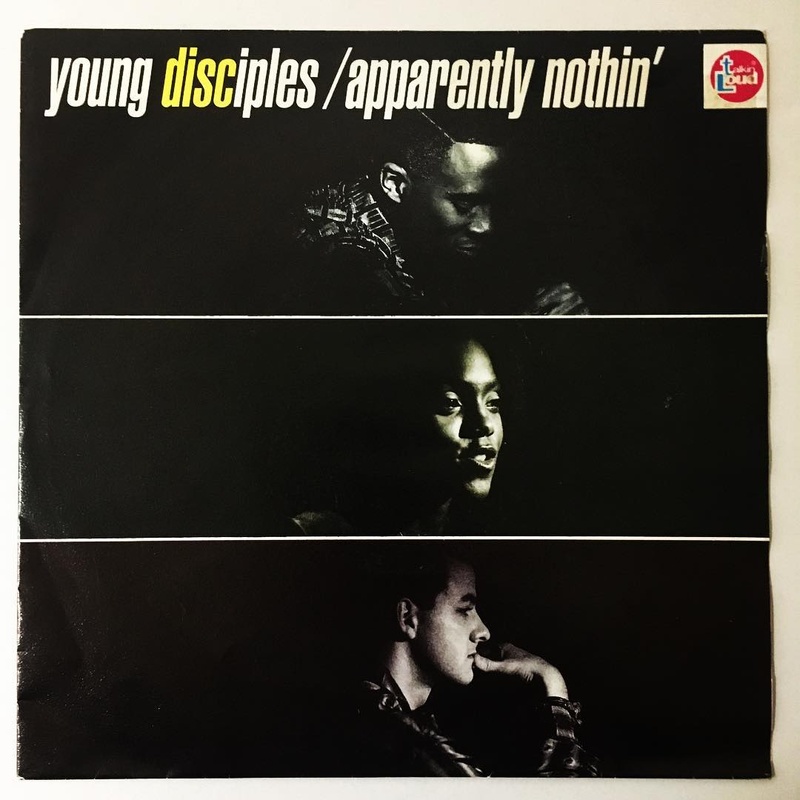

Then what happened was that hip-hop was really taking effect and that Gang Starr tune, “Jazz Thing,” hit that summer. The Young Disciples came to me with Joe Henderson’s Mode for Joe on Blue Note Records as inspiration for their new album, Apparently Nothin’. I thought, since hip-hop was sampling old music and turning it into something new, I’m going to do the same with the visuals. That was where it all started for me, the whole appropriation, visual remixing thing.

Your graphic designs definitely have some synergy with music production. Like the sampling of records with all sorts of machines, to loop and sequence. That fusion of the analog and digital. There’s this element of rawness in your work. It feels hand-made, less clean. Can you speak a little bit about that?

My other big influence was the American designer Saul Bass, whose typographic sensibility had such a playful energy about it all, and it was all hand-drawn. So, I started drawing a lot of stuff by hand, and then scanning back into the computer…

By scanning you keep the integrity of the physical object. Like, there’s these rough edges, these bits of artifacts and smudges that derive from the process…

Exactly, it’s not clean. You haven’t got a corner that’s perfectly crisp. It’s unique, a bit of a random seed, if you like. Also when you’re drawing stuff by hand, it’s like you’re free to express yourself more. When you’re designing something on a computer, it was within the parameters set by the software developers.

What does it mean to be known to have your own style?

At the time, I wasn’t even thinking about it. It was all purely improvised. You can only break new ground when you throw away the rulebook about design and go with your instincts. I was so busy that I didn’t really even have time to think about all that sort of stuff. It was work from Straight No Chaser and Gilles Peterson with Talkin’ Loud. In those days it was an album and three singles, and on the back of each release, there’s all the point-of-sales adverts. Then I’d meet someone in a club and they’d go, “Oh, you’re Swifty. Right, okay.”

How did your love for the camouflage pattern come about?

My dad was a ballistics expert in the Army, and as a result the military thing was a big thing in our house. Of course, I played with Action Man in the ’70s. As I moved into my adolescence, I wore vintage Army gear, because Echo and the Bunnymen were wearing it. I drew camo as a kid. For Addict clothing, I designed a line of camo apparel. When I started painting in 2006, it was of camouflage. Camo is what I have always loved.

Why did you decide to start Studio Babylon?

Timing was everything. I had started a family. Leaving the East for the West, we bought our house in Ealing. I started Studio Babylon in Ladbroke Grove, where I employed quite a few people.

Did you consciously decide that Studio Babylon was going to be different from everything you had before?

Yeah. At that point, I had designed two album covers for Blue Note Records called Mo’ Deep Mo’ Phunky and Make It Deep And Phunky. They were the two I loved most. I thought I had achieved everything I had set out to do. Studio Babylon was the new chapter.

We owned the Fosters Ice Street Art project. This was 1995. Fosters wanted to do something edgy with graffiti on billboards. I came up with the concept “Street Art,” as graffiti at that time was a very dirty word in advertising circles. It has never been looked into, but I’m certain the term “Street Art” had never been used in print prior to that campaign. We also wanted to work with a range of creators from musicians to photographers and artists, like REQ from Brighton and Futura 2000. The logo I had designed for Fosters Ice was on cut-out stencil to easily apply the same branding everywhere.

You started making artworks in the 2000s. Why did you feel the need to make your own art?

By 2006 I was very disillusioned with the graphic design industry. My design career had started to slip. Because of iTunes, suddenly we weren’t designing as many albums, singles, cassettes, and the rest of it. My income was slashed considerably pretty much overnight. I had to diversify. Also, it was my rebellion against digital technology. I was bored of the computer. I really want to get back to doing stuff by hand. I went and enrolled at an etching class, taught myself to silkscreen prints. I started painting, making very nostalgic, memory-based assemblage works that were all based on stuff that I absorbed as a kid: Gerry Anderson’s Thunderbirds, UFO, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., James Bond, you name it.

How do you fight a creative burnout?

I never stick with one thing. I get off on being inspired by new things, but can easily return to something else. For instance, I will return back to the camo, or to designing vinyl record covers again. I think that the variety and diversity of projects kept me going. I just change directions all the time.

As a self-employed creative, every morning when you open your eyes, you have to believe in yourself. Because there’s no other fucker there to help you. So, if you can’t open your eyes and go, “I’m the greatest graphic designer that ever lived, I’m going to have my breakfast and get on with it,” then you’re fucked. You have to have an ego. That said, at the same time, you have to be grounded.

But you were obviously receptive to what the world threw at you as well. Not many would have packed their bags and left Manchester just like that.

No, I was the only one in my family that left the North. Just reminiscing, I didn’t plan any of this. There was no plan. I just did what felt like the right thing to do at the time. Just going with the flow.

Ian Swift Recommends:

Captain Scarlet and The Mysterons Title sequence

Saul Bass - The Man with the Golden Arm poster

Buzzcocks - “Orgasm Addict” 7” sleeve

- Name

- Ian Swift

- Vocation

- Designer, Artist

Some Things

Pagination