On creating work while living with chronic pain

Prelude

Michelle Rial is an illustrator and the author of Am I Overthinking This and Maybe This will Help. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Wired, Fast Company, Vulture, and more. She is growing out her bangs.

Conversation

On creating work while living with chronic pain

Author and illustrator Michelle Rial discusses writing through the grief of losing a parent, working amidst chronic pain, why comparison is never a good idea, and the benefits—and risks—of obsession.

As told to Janet Frishberg, 2593 words.

Tags: Art, Illustration, Mental health, Creative anxiety, Inspiration.

I listened to this City Arts & Lectures conversation recently, between Rachel Kushner and Heidi Julavits, where they were talking about how every book is the writer trying to solve a new problem artistically. I’m curious what problem you were trying to solve with each of your books.

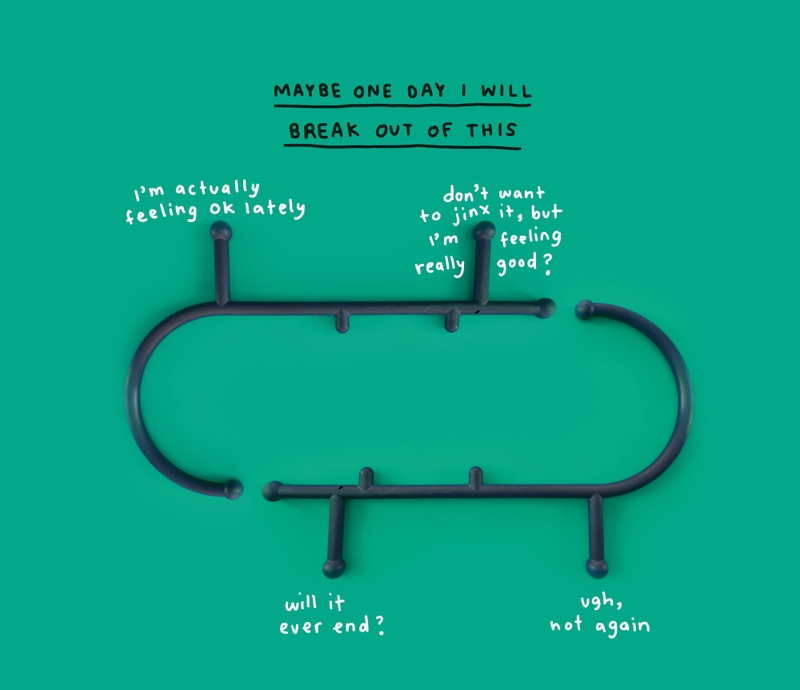

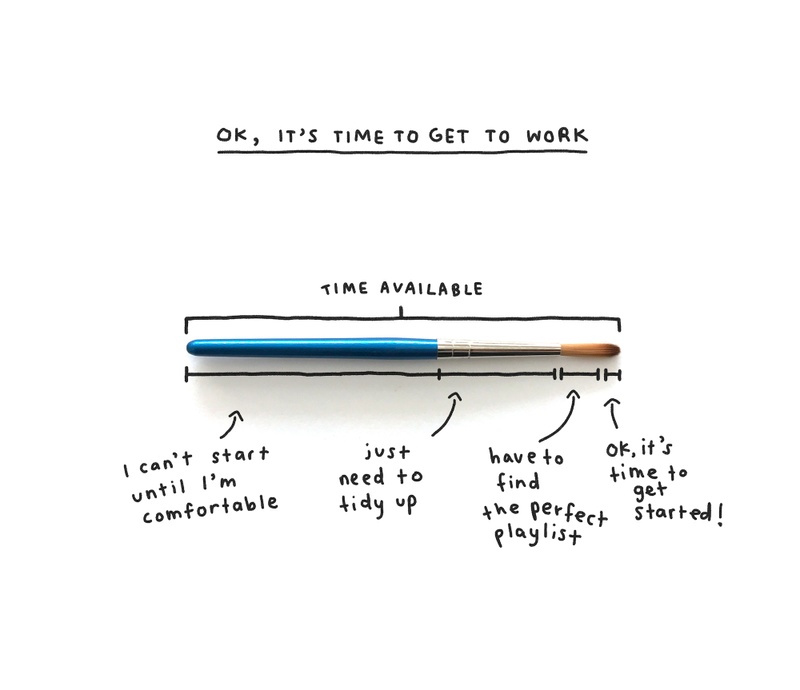

For the first book, the question was, “How can I write a book, how can I express myself creatively, when I physically don’t feel like I can?” And that was creating that style, using objects. This second one was, “How do I write about pain, when I can only really write about it when I’m not feeling it as much?” The work doesn’t feel as authentic at the time when I can physically do it. And then, when I am in the most pain and have what feels like the most urgent, important thoughts, I’m just like, “Nope. Can’t do it.”

When I’ve been in really intense bouts of pain, sometimes I’ve tried recording voice memos to capture the thoughts, but then later I listen to them and I’m like, “I don’t know what to do with this.”

Yeah, that seems like the obvious answer—speaking. There’s also this sadness and I don’t know what to do with that. Even with this book, I look at it like, “Ugh, what are you complaining about? Why are you so emo?” It’s almost like my more able self judges the sadness of the less able self.

I noticed that screaming into the abyss was in your acknowledgments. That’s also been a super important part of my process the last few years. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

That’s funny that you caught that. It’s a nod to Garden State, when they scream into the quarry. I always wanted to do it. It was one of those very romantic moments. So, when I was at peak rock bottom, which is an oxymoron, I was on a hike with these people that I didn’t know well. I was in one of those very charged moments where you’re just living fully, because you’re feeling everything. And I had everybody do the screaming into the abyss. It was one of my most alive moments. Like… you’re at rock bottom and you’re acting like a person you aren’t. I’m not somebody who screams or wants to be seen or wants to be heard. Even if I have all the space in the world, I’m going to be wondering who can hear me and what they’re thinking.

In a lot of my reading relating to chronic pain, everyone swears by Dr. John Sarno. He says that chronic pain comes from, I believe, unexpressed rage. So part of it, I think, is expressing that rage. It’s not sustainable… I can’t scream all the time and I can’t be releasing rage constantly. But sometimes it helps.

Yeah, it does. In a few of your charts you talk about comparison and creativity, which I think is an issue for a lot of people.

I’ve been thinking recently about creativity in a fight/flight/freeze scenario. I think comparison can create all of those. Like, you’re comparing yourself to someone else and you want to fight them. You get this feeling like it’s a competition. Not me, I’m a flight or freeze. When I start comparing myself to other people, I stop having ideas, because I don’t want to do it anymore. My brain just stops. Comparison is always really bad.

What’s the alternative though?

No matter how close that person’s work is to mine, it’s still different. This is still my brain that has been through totally different things. It’s going to be different if I keep going at it. If I stop, then of course, everything I do will have been done. But if I keep going, something will come out of it.

Is there art that’s given you permission in the process of writing your book?

So, I have a creative license—literally, it’s a license to make art—from Hallie Bateman. I don’t know if she’s doing them right now. But you send her a picture of yourself and it’s like, your favorite color, your inner animal, and a few other things. She makes you a laminated creative license with a cute, illustrated version of you. And it felt real to me. It’s such a good little item. You flip it over and on the back it says something like, “This is a license to make art. It doesn’t have to be good.” And it works.

When you’re creating your charts, do you have an imagined reader in mind? Or how do you relate to the work being seen?

It’s weird because I’m so private. I alternate between closed off and very open. I get energy out of connecting over things that are rare, that you experience along with someone else. I envision that person who’s like, “Oh, I didn’t know that anybody else did that. I have that one weird thing, too.” I like it to be something that’s very specific, that hasn’t been over-memed already. Which is getting harder and harder, you know? Every little emotion has been exploited at this point.

How do you know when a chart is done? I’m curious how you distinguish between the voice of insecurity that’s like, “Nothing I do is good enough,” and the voice of wisdom that’s like, “This actually needs more time to bake.”

I don’t know. Right now I’m just in the insecurity portion and nothing feels good enough. But I think one way that I can answer this is, if I go back to it and I have a little chuckle with myself, then I feel like it’s good. I still think it’s funny. There are some parts of this new book that I look back at and I feel mortified. There are some parts where I’m like, “Wow, this person really gets me. This me really gets me.” And it feels good. Because even though it’s me, I’m really connecting with it. And hopefully, someone else will feel that way.

In the book you talk about, “the irony that the more pain you have the more weight that you need to carry.” What are your favorite helpful things to carry these days?

I don’t carry this with me, but I move it around the house. It’s a butt cushion. I don’t know the actual term for it but I think if you Google “Cushion Lab butt cushion,” you’ll find it. It’s a gray, nice-looking thing that gives your tailbone space to breathe and makes your back feel okay when you’re sitting in different places. I have my ergonomic desk I can sit at and everything’s perfect. But I never want to be there. So, now I just move my little cushion around.

What do you think that’s about? I’m the same. I can set up my whole thing and then I don’t want to be there.

Yeah, I want to be on the couch in a living room where it feels cozy. Ergonomic and postural things are always so ugly. I don’t want to see that stuff all the time. When I worked at a job where they actually accommodated and got me the chair and elbow platform that I needed, I would walk into the office and my desk looked like this rocket ship.

Anything accommodating for pain always sticks out really intrusively when you just want to be invisible. But if I could, I would bring my little cushion to the coffee shop.

Maybe you will, post-pandemic.

Yeah, I’ll put a little handle on it like a briefcase and just carry it.

Exactly. How did this book come to exist?

It came to exist, actually, before my first book. I wanted to write this book and then I pivoted into my first book, instead, because it was less serious. It was like, “Nobody knows who I am. Nobody cares what I’m going through. So I’m just going to make this fun stuff.” When I started out, I had these chronic pain issues and I had just quit my job because I couldn’t do it anymore. I had gotten this injection that was supposed to make things better, just like everything else, and it actually, just like most things, made it worse. I couldn’t do anything. I was just lying on the floor.

I wanted to use my brain a little bit. So I’d make these really basic, stupid, rough charts that’d be, like, two lines. That’s all I could do. And all I could think about was how much pain I was in and how depressing it was. That’s what I was making them about. Because I was depressed and had nothing going on, I also didn’t have that many creative ideas. So all I was writing over and over was, “Maybe this will help,” in big letters on a paper. And I was like, “What if this could be a book one day?”

In the second book, there’s this interweaving between your chronic pain story and then the story of your dad’s illness. For the parts about your dad, were you writing them as they were happening? Or was it after his death?

That wasn’t going to be part of it at all. It wedged itself in, in a way. The most significant parts of his illness were when I was in a really creative space. I was drawing some of the little diagrams and feelings while it was happening, around the time my first book was finishing up. I don’t generally write essays, but I wanted to give context on these sad charts that were happening. I wrote everything after he died, about a year later. But it was very fresh and charged because it was during the wildfires last year. It was this time when I would’ve been asking him a lot of questions, because he studied abrupt climate change.

I think about friends who have parents who do useful-to-you professions. Like you can ask them, “Hey, can you ask your mom what this rash is?” I always felt like I could email him whatever article I’d just found and be like, “Should I be really scared?” And he would reassure me, in a way. Less so, as time passed. So I felt like I had lost this reassurance that you get from a parent, sometimes, but also this source that I trusted on climate, that was very close to me.

I was writing one of the essays during the day when the sky was orange in San Francisco and it was very apocalyptic and I was just sort of sobbing at my desk—I actually was at my desk that day—thinking of all the things that were wrong and writing my book.

This is kind of a simplistic thing to ask, but was it helpful in some way? To be writing about it?

It was. Like, “Oh, I’m feeling really sad and helpless about what’s going on in the world. And my computer’s right here in front of this apocalyptic scene. So, I guess I should write about it in the ways that I’m feeling.” It felt really cathartic; I was just crying and writing. And there was this half-feeling where I was almost watching myself like, “Oh, this is probably going to be good, if you’re sobbing and writing.”

Like, “This is gold.”

Yeah. And then part of me was also just sobbing and writing.

Is there anything you’re currently obsessed with?

Oh my god. Yeah, I go through my obsessive phases. I’m obsessed with Japanese Maples. I’m obsessed with trees and knowing what every tree is. I have the PictureThis app. I’m always in this searching thing, where it’s always a little bit related to getting better. There’s part of me that’s like, “This thing I’m doing is just out of enjoyment.” And then, in the back of my mind it’s like, “Oh, but maybe it’ll help you heal.” But then I have to make some kind of obsession out of it. So, now I’m like, “That’s poison oak, that’s blackberry, that’s a pin oak.” I just want to know. I can tell by the tree ring, I can tell by the bark, I can tell by the leaf. I think it’s fun. I also am obsessed with Ginkgo trees. But that’s been for a while. They’re so beautiful.

How do you think about obsession as it relates to art making?

The obsession makes it better and worse. It never being done and it having to be perfect can be why it’s good. Because nobody else would take it that far. But then also, it can take away the surprise and the organicness of something. It’s like when you blurt something out that’s really funny, it’s not going to be the same as if you… say it in cursive, is what I keep thinking. It’s not going to be as funny if you arrange it perfectly.

I have a lot of obsessive qualities and they definitely overlap with the chronic pain stuff. It’s like, “I cannot stop right now. I will not give myself a break, because this has to be perfect. I will not step away from the computer. I will not quit this job that is torturing me.” Not in my case, but I do think obsessiveness is what can create some kind of masterpiece, when you’re really obsessed with every single detail, somebody can tell that that much thought was put into it.

Advice giving is tricky, but do you have any advice for people who want to be a good friend to somebody who’s in chronic pain?

I do. It’s to ask them the question that you asked me, just now.

“What can I do to be a good friend to you?”

Yeah, “What can I do?” And then also ask them, “What are the things that cause you the most pain, and can I do some of them for you?” Is it as simple as carrying groceries? Or pulling laundry out of the dryer? Or putting on the fitted sheet, for some reason, is so hard.

I know!

One of the most tender moments I had was with this friend group that we like to see comedy shows with, especially when SketchFest comes to San Francisco. I don’t often tell people how they can accommodate. It feels embarrassing. I’ll just do my own thing, plan in advance and work around it in a way that is very private and alone. But once I told these friends, “Can we try to sit in the middle of the venue? Because otherwise, my neck starts to hurt if we’re on the side.” I just said it one time. And then the next time we met them they were like, “We saved seats in the middle for your neck.” And I cried, because it was so sweet. It was such a small thing that meant a lot.

Michelle Rial Recommends:

Vionic house slippers with arch support

Yamamotoyama decaf genmaicha

Lying under an aspen tree in the fall

PictureThis, an app for identifying plants and trees and things that are poisonous

Not tweeting

- Name

- Michelle Rial

- Vocation

- Author and Illustrator

Some Things

Pagination