As told to Willa Köerner, 3739 words.

Tags: Art, Business, Technology, Architecture, Beginnings, Success, Collaboration.

On bringing the future into the present through radical collaboration

Carmen Aguilar, Ece Tankal, and Ashley Baccus-Clark of Hyphen-Labs discuss the forces that led them to each other, getting their interaction studio off the ground, and coming up with their own definitions of success.What led you to one another, and how did you decide to form Hyphen-Labs?

Carmen Aguilar: I found these two girls in academia. I went to undergrad with Ashley, she was one of my dorm mates. It was our freshman year, and we were learning all about independence together—all about what it was that we were studying, what we wanted to do, and what we were passionate about. We were at UC Santa Cruz together for two years, and after that, we stayed very involved in each other’s lives.

Later, when I was thinking about going to grad school in Barcelona, Ashley had been living in Berlin for a while. So I went to visit her to see what that kind of life would be like. I was at a point in my career where I was studying engineering, but I realized I wanted to change my focus completely. I ended up going to school at EAC in Barcelona, and started studying advanced architecture and interaction design. And that’s where I met Ece.

Ece was the first person to introduce herself to me at school, because for some reason I’d said I’d gone to Burning Man when we were asked to say something weird about ourselves. So she came up and was like, “Who are you and what are you doing?”

From that point on, she started exposing me to a perspective that I had never seen before. Engineers and architects weren’t necessarily co-mingling in my world, and this was a space where I was able to start collaborating and seeing things from their point of view. After we graduated, we started working together in smaller interaction studios and we were like, “Man, we can do this by ourselves, we don’t need to be working for other people.” So we decided to open Hyphen-Labs.

What was the first project that Hyphen-Labs made?

Ece Tankal: The first real project we got was the two of us working on a kinetic installation inside of a tech company’s headquarters.

Carmen Aguilar: Yeah. The piece is called Prismatic.

Prismatic Kinetic Sculpture, 2015.

Prismatic Kinetic Sculpture, 2015.

Did you have pitch yourselves to get that first professional gig? Or how did it come about?

Carmen Aguilar: I think it came down to network, where I knew someone who knew someone who worked at Bot & Dolly, which at the time was one of the companies doing dynamic projection mapping with these large robots. And we were using these large robots in our work. We went in for a casual meeting, like, “You know, we wanna meet you guys, we’re really inspired by your work.” And we showed them our portfolios, and they had just been acquired by another tech company, so they were like, “Oh, we have this one last project. And we like your style, we like your work, so we’re going to take a risk and we want you guys to create and direct this.”

So when you started putting your first gigs together, was this all of your full-time jobs? How were you able to come right out of school and then just jump into doing your own thing?

Carmen Aguilar: Ece and I got out of school and started working for another company. While we were working for them and they were paying our wages, we went and found this other big job that ended up supporting us for nine months.

Ece Tankal: Also living in Barcelona, the cost of living is a lot cheaper, so it’s a bit easier to sustain yourself. It’s not like in New York where you have to constantly be thinking, “Oh, what am I gonna need that this month,” you know?

Carmen Aguilar: Our rent was like 300 euros at the time. And we didn’t have to pay for health insurance. But then when we did get to a point of knowing what we wanted to do, that’s when I decided to move to New York, while Ece would stay in Barcelona.

Back in New York, I started attending the School for Poetic Computation, which is when Ashley comes into our story. Because of all of the factors of living in New York and going to a school that was talking about technology, ethics, language, cybernetics, and robotics, that’s where Ahsley and I started talking about what representation looked like in these fields.

Ashley Baccus-Clark: Yeah, I can chime in here. So these girls are like my sisters and I think we feed off of each other’s energy. When Carmen came to New York, it was the first time that I got exposed to how she and Ece were working together. I think I met both of you in Rome, while I was on a hiatus from grad school and working for Warby Parker doing retail operations. At that point, Carmen was like, “I have a show in Rome, why don’t you come?” So I got there and she and Ece were there, and we had a crazy experience where we went to a maker faire, and I was like, “Yo, what they’re doing is sick.” I was at a point where… I studied science, and I was trying to figure out if I wanted to go back into science or if I wanted to do something else.

And so yeah, Carmen moved to New York, where I had moved a couple months before to join the brand marketing team at Warby Parker. So I was deeply entrenched in the corporate world, and I was tired of it. While Carmen was in the School for Poetic Computation, at night she would bring her reading home and I would read it out loud and she would cook dinner, that was the trade off.

That summer was a pivotal moment in the fight for Black Lives Matter, and there was all of this media attention around the extrajudicial killing of Black men. And I’ve always loved writing and loved storytelling, so one night Carmen and I were kind of riffing off each other and we thought about an idea. We got Ece on the phone, and we were like, “Hey, we have this idea, how do we make it look bomb?”

What was the idea?

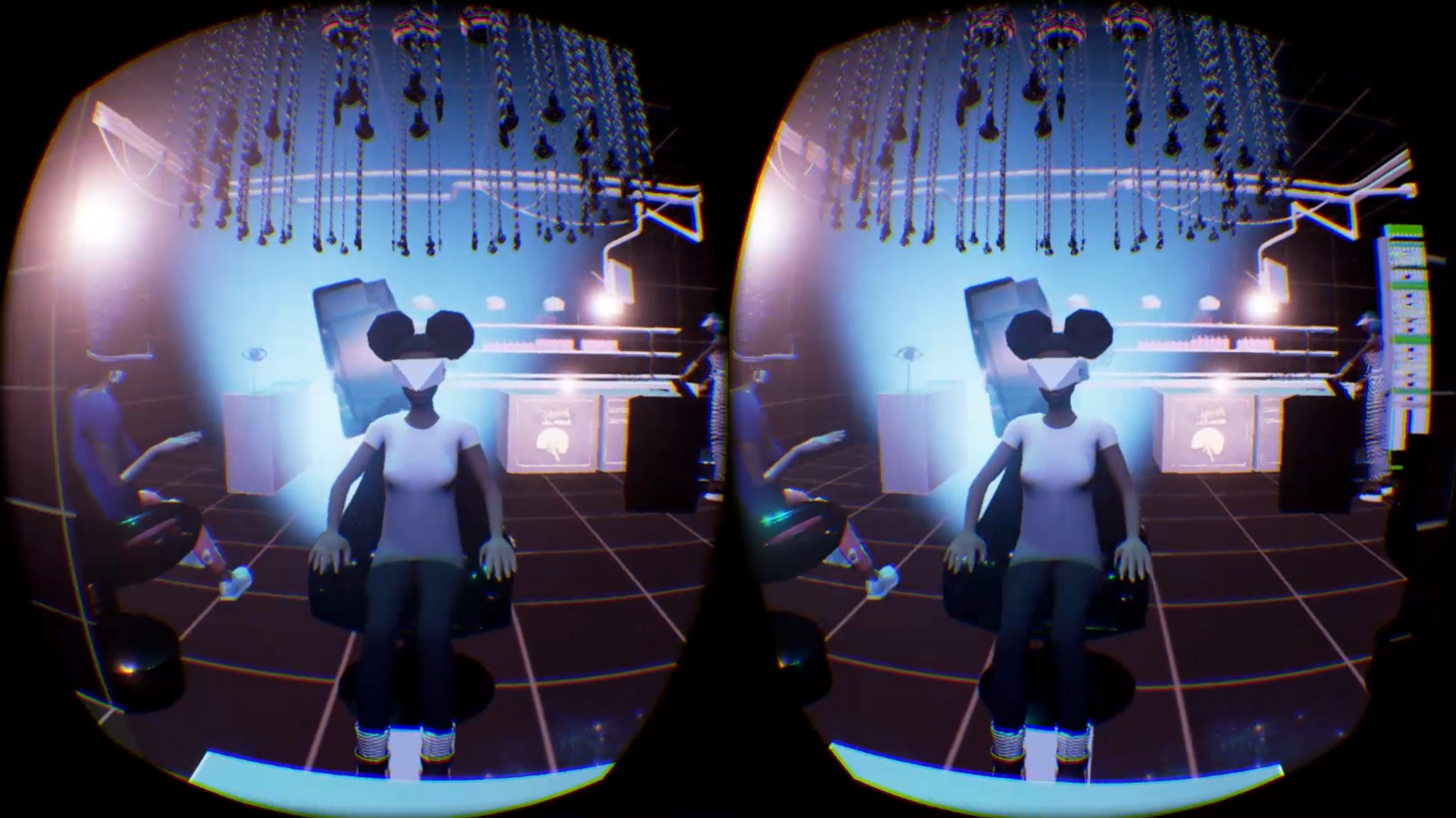

Ashley Baccus-Clark: The idea was for our first project together, NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism, or NSAF. It’s a three-part project. One part is looking at object design, the next part is virtual reality, and the third part is doing cognitive impact research around virtual reality and emerging technology. We see how it’s impacting us as humans, as well as how it can be a tool for addressing prejudice and bias. So, looking at how we can triangulate our thinking about diversity initiatives and technology in general, on a monumental scale. We hadn’t seen Blackness or Black womanhood really put together in that way, so we created an entire platform around it.

So yeah, I think that was a transition moment for us. From that, we got into Sundance, we showed it at New Frontier there, then we showed it at Tribeca, we showed it at South by Southwest, and we really got to engage with the community.

NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism Installation, 2017. Tribeca, New York City.

NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism Installation, 2017. Tribeca, New York City.

Can you describe the model that you have going now, in terms of how you decide which personal projects to work on as Hyphen-Labs, versus things you’re paid to do for a client?

Carmen Aguilar: We do it all. We have to, I mean… we don’t say no to really any opportunities because, one, we want to expand our repertoire of the tools that we use. Two, we want to access different types of people. And three, we’re very lucky to be represented by a production company in Brooklyn called Missing Pieces. They do a wonderful job of pairing us with companies or larger brands that have a cause.

Ashley Baccus-Clark: We’re not too discerning about what types of jobs we take on, but we are discerning about who we work with and the integrity of the company, or the integrity of the project. Does it have social impact, are we making a difference, are we challenging people to do better or to think differently?

Overall, we can’t afford to not be well versed and smart about the marketing side of things, the branding side of things, the fabrication, and the production, because we need to support ourselves. We want to be a self-sustaining entity no matter what we do, and we’ve found that we have to be smart about all of this stuff or else we’re not gonna be able to keep the studio open and we’re not gonna be able to do the types of projects that we wanna do.

NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism, Objects, 2017.

NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism, Objects, 2017.

How did you figure out how to balance those objectives, between doing work that you find important and meaningful, versus just needing to have a certain level of income?

Ashley Baccus-Clark: By reading everything, and thinking about business strategy, you know? We’re all trying to fill in our gaps of knowledge, and think like business women.

Ece Tankal: Also, from a practical side, with each project we learn something new—new tools especially. Like, we shoot commercials even though none of us had worked in a commercial shooting scene before. We go in, and we learn as many things as we’re exposed to. Usually when we’re doing commercial work, it’s not necessarily the outcome that matters most, but mostly the process of how things get done. So in any situation, we can feed off of our curiosity around making things.

So as a team, Hyphen-Labs now has 12 members. How do you navigate working with all these different people, all with different skills? And how do you stay organized while working with that many people, who are all in different locations?

Carmen Aguilar: When we were in school, we were working in a space that had something called a fabrication laboratory. They’re these global fab labs that tend to have a laser cutter, a CNC router, 3D printers, circuit board milling machines, and a bunch of different prototyping tools. And we found that in any city we went to, we could find these places—but we weren’t represented in those spaces. It was always a guys’ game, and it just didn’t feel like there was the same kind of collective that was made by women anywhere else.

So when we started Hyphen-Labs, we wanted to create a kind of network of women who were in these industries to find each other. And so we started working with specific women that we would meet, and we would try to develop a project together. And a lot of them have their own visions or their own practices. But if we come across a project, we know that we can propose it to them and if they are interested in collaborating with us, then we reach within our network first.

So it’s sort of like you three are the core group, and then the rest of the team is more like a network that you can tap into when you need to?

Carmen Aguilar: It’s really fluid, you know? Sometimes I can be more involved, sometimes I can be less involved. Sometimes Ashley is more involved, sometimes she’s less, same thing with Ece. So we wanna be flexible, we wanna be less defined. We don’t necessarily want to run it with a hierarchy that is set in stone, or that makes us the decision makers or the leaders or something. We also want to work with other people and be led by each other.

Has that fluid structure generally worked out? Or have there been instances where the fluidity creates tension, or miscommunication?

Ashley Baccus-Clark: Learning how to collaborate well is what’s missing in a lot of different arenas. And so it’s just been a lesson for us—because we are so close, and because we know each other so well, we tend to collaborate very differently than if we were working on things with people we don’t know well. There has to be an emotional intelligence that we bring to our collaborations. And Hyphen-Labs has been a sandbox for us learning how to do that.

Carmen Aguilar: One of the biggest things we’ve learned is contracts. Set up contracts before you get involved with people. And figure out where the intellectual property lies, and what the deliverables are. Contracts make things much easier for us, as both client and as service providers. In our early days we’d be like, “Okay, we’re gonna do this thing and we’re gonna try to get 500 pounds for it or euros or dollars.” And then we’d spend all night, but because we didn’t have a contract, things often didn’t work out the way we expected it to. So I think that’s one of the most important things we’ve learned as far as collaborating goes.

Another thing we’ve learned the importance of is sticking to our hourly rates, and what our own value is. Once we figure out what that is for any project, if the institution can’t meet that, it’s important to change what we will deliver in order to match what they can give us.

When you’re trying to communicate your value, is that something a client needs to understand inherently, or are there ways of describing what you do that helps underscore the value you bring to a project?

Carmen Aguilar: I think it starts with us, internally understanding the value we bring. Like, we have been working within our own sectors for long enough that we know that we can do this. We’ve failed with enough projects, we’ve succeeded with enough projects, and we’ve been able to experiment in enough mediums that we had no idea about and made something successful, that we understand our own value now.

There’s that term, “Fake it until you make it.” That was something that I always felt like, “Okay, I can do this, even though I don’t know how.” And now I don’t feel so afraid to say, “I don’t know how to do something, but I know how to think and I have brilliant women around me who also get me to think in alternative and exciting ways. And we want to offer that mode of thinking or working to the world.” And I think that that’s where it’s not like, “Oh, we are valuable, so please believe us.” We just believe in ourselves.

Of course we have our own anxieties, and we have our own insecurities—everyone does. But we also have a really amazing framework to fall on if we need to fall, because we have each other. As friends first, you know, and if things get complicated—which they do—we know that our friendship will always be there, and it’s not one person’s responsibility to make this successful. It’s all of our responsibility.

Ashley Baccus-Clark: It’s a new way of thinking about how to run a business. We really want to be able to offer people space to fail and to make mistakes, but also to learn and grow from that. Because some of the best work comes out of those mistakes. And it’s not all about the financial piece—it’s about how we’re growing as human beings.

NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism, 2017. Virtual Reality.

NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism, 2017. Virtual Reality.

Can you talk more about your experience working in ways that are new, or unusual, or maybe a bit futuristic? As a company that tends to work at the edge of what’s established—both in terms of ways of working, and the technologies that you work with—how do you see into the future, and ground that work in the present?

Ece Tankal: I think the present is too occupied right now with problems. Brexit, walls, a lot of climate things. We want to create this… not necessarily this super utopian future to tell people like, “Hey, this is how it should be”—but bringing in these elements from the future so that we can inform the present. Because sometimes I feel like the present doesn’t let us have a lot of imagination.

Carmen Aguilar: Maybe it’s not necessarily going into the future and grounding it in the now, but it could be taking us and our communities and our friends and our families and bringing them into the future by asking where we see ourselves going next.

Ece Tankal: Yeah, so that they can actually start imagining what that process could be. Like, what can we do to get to that point, you know?

Carmen Aguilar: And then when it comes to the work, tying it into something familiar that we know, that we see, that we experience. We have a lot of things that are familiar in rituals or locations or objects, or other things that we all inherently know how to interact with.

Ashley Baccus-Clark: I think it’s important to use the future to rewrite some of the more painful points of the past. You know, to re-figure and kind of move past this collective trauma of what’s happened in the past by re-imagining how the future can take shape. Personally, that’s a lot of what I think about—how can I disrupt ancestral trauma by living fully in the future, and in the present, too.

Building on these ideas, how do you define success in your work?

Ece Tankal: I don’t think it’s some external thing. It’s not like people applauding for us, or giving us money or whatever. It’s more like, at the end of the day, you look at the things that we did and—even if nobody sees that work—it feels like, “We did it.” If it was empowering for us, that’s successful.

Carmen Aguilar: For me, success can be meeting somebody after an installation and seeing them thinking. And getting them to a point where they’re like erroring themselves.

Erroring themselves?

Carmen Aguilar: You know, getting people excited, getting them thinking.

Painkillers, 2017.

Painkillers, 2017.

Another thing that I’d define as success is just making something, and finishing it, you know? When we’ve screwed all of the hands into the walls or we’ve put the plugs somewhere, we’ve fabricated the boxes. Maybe success is not the huge overall effort, but it’s in the small details of like, “We ordered all of the pieces, they’re on time, everything is on track,” so we’re not constantly anxious.

Ashley Baccus-Clark: I was gonna say that success is just seeing our moms’ reactions, you know? Like when I see my mom—who doesn’t even really know how to text—has a piece of paper and she’s written down some part of a project that we did, to tell her friends about it. Even though she might have the words all wrong—that’s exciting for me. ‘Cause like, you know, they’ve given so much so that we can be where we are, and to have them feel proud and included and seen in our work, that feels like success.

Ece Tankal: Also, I think they are the most critical ones, no? They’re not constantly cheering for us, or at least my mom definitely isn’t. She’s our biggest—

Carmen Aguilar: She is the first to like all of our social media posts.

Ashley Baccus-Clark: She’s our first Twitter fan!

Carmen Aguilar: We’re all very close with each others’ moms. While Ashley’s in L.A. setting up one exhibition, my mom will come help me set up something with Ece in Miami. We can really integrate them into our process, and that’s so rewarding.

If you could go back in time to five or so years ago, and give yourselves one piece of advice, what do you think it’d be?

Carmen Aguilar: Well, it’s our five-year anniversary. We started in 2014. Since then, I think one of the things it’s taken me a long time to get to is that other people’s critiques of you or your work have more to do with their own insecurities, and you don’t have to take their critiques as truth. You’re not going to please everybody in the room, and the more that you can make people wanna talk about the work that you’re doing, the better it is.

What I learned from architecture school was that when someone showed a final presentation and there was no discussion, then the work really needed to be developed. But when you get people excited about it and you start sparking these conversations, that’s when you know you have a kernel of an idea.

Ece Tankal: My piece of advice would be to leave the comfort zone of whatever place, or whatever medium that you’re working on, or the people that you normally interact with, or the ways you communicate. When I was younger, I would just keep working on the skills that I already had, so I was always in my comfort zone. But now I know that it’s important to do the things that you think you cannot do.

Ashley Baccus-Clark: Mine would just be to take graphic design in school.

Ece Tankal: What about you?

Ashley Baccus-Clark: Oh yes, can we ask you, actually?

You want me to answer it?

Carmen Aguilar: Yeah.

Okay, hmm. My answer is to stop waiting for other people to give me opportunities and to just make my own.

Ashley Baccus-Clark: That’s a good one.

Yeah. Because I think when you get in the mindset of, “I have to apply for this, or if I could only get this job, or if this person would invite me to do this thing,” you’re just gonna be waiting around forever.

Carmen Aguilar: That’s very true.

Hyphen-Labs recommends:

-

Book: As radical, as mother, as salad, as shelter: What should art institutions do now? Edited by Paper Monument

-

Film: “US” by Jordan peel

-

Idea: Subaltern counterpublics

-

Artists: Frau Fiber & Yara Travieso