On the process of processing

Prelude

Yo-Yo Lin 林友友 is a Taiwanese-American, interdisciplinary artist who uses animation, performance, and sound to create meditative ‘memoryscapes.’ Her recent body of work reveals and re-values the complex realities of living with invisibilized chronic illness, investigating ideologies of healing, resilience, and care. Her practice often facilitates sites for community-centered abundance, developing into physical and virtual installations, workshops, accessible nightlife parties, and artist collectives. This year, she debuted her latest performance “channels” at The Shed to a sold-out house. She is currently developing and teaching her course “Media-making as a Healing Practice” at NYU ITP and was recently selected for the 2022 Disability Futures Fellowship. Born and raised in Los Angeles, she lives with her partner and growing collection of houseplants in Brooklyn, NY.

Conversation

On the process of processing

Artist Yo-Yo Lin discusses using her everyday life in her work, art as a refuge and pathway to communication, and how lying can lead to burnout.

As told to Joselia Rebekah Hughes, 3703 words.

Tags: Art, Process, Identity, Success, Collaboration.

How or when did you realize you would become an artist?

As a kid, I couldn’t do a lot of things because I was disabled. In medical terms, I grew up with Marfans. In every-day terms, I couldn’t run around and kick the ball and do [things] like the other kids.

I was always really good at drawing. I was that kid that didn’t talk and just drew. I didn’t talk a lot because English isn’t my first language. Also, looking back, I have social anxiety so I didn’t really like talking to people. I would make intricate drawings with crayons and colored pencils. I remember once in PE, Ms. Pollard [instructor’s name] gathered everyone. I had made a poster or something for her as a thank you. I don’t remember exactly. She got all the kids together and said, “Look, everyone! Look at what Yo-Yo drew.” Then kids were just like, “Oh, amazing” and “Nice.” Ms. Pollard said, “Sometimes when you can’t do something, you’re gifted with other things that you can do.” I remember that moment being extremely embarrassing because I didn’t want that [interpretation of my condition] to be the takeaway from the drawing.

As an adult thinking back on this memory, I’m realizing so much of my experiences growing up disabled were about using art as a pathway to communicate, to have something that I could do and be good at it, and to be told I was good at it. Art is within my range of control. My parents were really supportive of me doing art because they realized it was something that I could do. The older I got, the more I realized art was always something that I had and held, could go back to and use as a way to better understand a situation, better understand myself, to ask certain questions without needing the language for it in words.

Art is also a place of respite in difficult times. Art offers me a place of autonomy and a place of refuge.

So much of what I do has been a means to better understand myself and to better understand myself in context, in relation to other people. There’s so much in my experiences growing up in an immigrant household, growing up disabled, and having all of these different experiences in which I didn’t have a lot of say of who I was, or who I can be, or who I could be received as. I became possible through the art of making processes where I was creating things that allowed me a fair amount of creative choice. Having that choice, that amount of exploration made it possible for myself within those processes, creates respite: a place where I feel, where I see my wholeness, see abundance, and see that my experiences are enough and have always been.

The process of making art for me is also tied to how I see myself and how I am in the world. I don’t know if I would be here if it weren’t for having an artistic process. I don’t know who I would be without it.

Image Description: Crouched on the floor and slowly rotating her shoulder blades, Yo-Yo, a Taiwanese American femme performs an in-progress of ‘channels’ with Despina in a white room with purple blue ceiling lights. She dances connected to wires hung on pulleys from the ceiling, connecting her to Despina, a nonbinary white person who sits at a table with synthesizers and speakers. This is from an open studio showing for the Brooklyn Arts Exchange at Dancewave in 2021.

Can you walk us through what a process looks like for you?

A process often starts from just being, from the day-life things I do. There’s so much in the mundane that has contributed to my process. I often start from a place of longing or desire. A lot of my process starts with me really wanting something to exist in the world, but it not being there yet.

Then I start feeling kind of incredulous that this doesn’t exist, or hasn’t been talked about, or hasn’t been talked about in this way, or seen in this way. Then I go into a questioning moment: Is this something that I do want to engage with? Do I want to bring this into the world? Is this the process that I want to run? If this is a road, is this the road that I want to go down? I think so much of my process these days has been creating with a sense of that feeling of respite. Can I create a film, or a story, or a project that can foster space for me to process these emotions, or these feelings, or create a space for me and others to move through a process of processing? So much centers on creating spaces for healing.

Earlier you mentioned relationships. How do relationships form and inform the work you make and life you live?

I grew up in a big family, so there’s always people around. We were always on top of each other. We would be back and forth, moments of us yelling at each other, or having more loving moments. I grew up around a lot of energies. Growing up in a big family allowed me to find my place among many. I was a middle child. I was a third child. I was the youngest daughter as well. I have two brothers and a sister. I was always in this place of being in relation to others. In that, I always knew family secrets. People told me things and I wouldn’t tell anyone else.

I learned during that time: I am this in-between person for these people in my family. I have noticed, now that I’m not with my family as often, things fall through the cracks a little bit. I think I try and often recreate these kinds of relationships with the relationships I make in my artistic practice. So much of collaborating with folks has been a process of how do we do this together, and how do we do this in a way that centers both of where we are in our individual practices, but also creates this third entity beyond us.

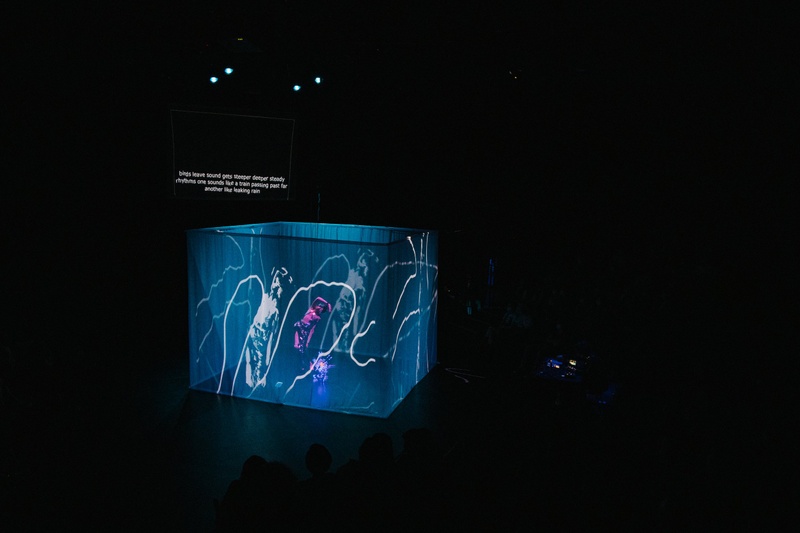

The relationships that I create in my practice have been, honestly, my most interesting work because so much of, let’s say, the channels performance, me and my collaborator, Despina, take sounds from my body, synthesized those sounds live into music, and then created a dance process. This was something I never would have conceived as being possible until I talked to Despina. We used to be roommates and, over a very casual conversation at the dinner table, I asked, “Can I take my bone sounds and give them to you? Can you make music from that?” They were like, “Yeah, of course. No problem.” The possibility of imagining this work was nurtured within the relationship we have. We’ve been working together for the past seven, eight years.

Relationships create new imaginations, new possibilities. That goes with every single collaboration that happens. A lot of the work that I do is about creating spaces…recreating an experience, or a space, or performance that hopefully brings people into a place that feels welcoming, or more intimate, or welcomes a place of introspection. I think that’s also why the quality of my work often turns out to be generative and meditative. There’s elements of me and my collaborators wanting to create a space for people to join us within what we’re creating. It’s not just the relationship between me and my collaborators, but also that relationship between us and everyone else that comes into the room.

How do you approach digital space? What’s your relationship with social media/email?

My family was always very interested in technology. My dad had a lot of different gadgets and always loved reading up on the newest things. I had access to computer games when I was like five years old. Interfacing with screens has been a very fluid part of my existence. But I have a complicated relationship with digital media, actually, because I have been working in it for so long.

I started my art practice drawing and painting. I would spend a lot of time in front of the easel. Eventually, I started moving towards animation. Because I grew up in this [digital] age, there wasn’t a physical way of doing animation anymore. It was all on the computer. That was a hard transition for me even though I grew up with digital media, email, and websites. Myspace, Blogspot, all that.

My gripe with working in digital media is needing to be sitting in front of the computer for so long. Especially when you’re working with animation and video, you’re sitting and staring at screens constantly. The ergonomics is just not… we still haven’t figured that out… especially for me and my body.

Despite that, there’s so many things that I was suddenly able to explore.

Creating different ways of witnessing and seeing myself has been a big part of it. I can set up a webcam and play with a bunch of different kinds of graphics and code, play with different kinds of software, and suddenly, manipulate how I appear, what I look like in movement. That ranges from Photoshop to something like TouchDesigner where there’s so many different ways that I was able to craft these different languages of how I appear. To have that ability to do that was expansive in understanding my visual languages don’t just end with what’s being presented to me here. I can actually use this tool to manipulate things further, distort things more to my own liking, and create things in a way that also helps and creates a deeper sense of possibility for myself.

Image Description: A wide shot of the space, a large black box theatre with seats surrounding the cube in a U. The fabric cube is luminescent in blue and purple with white gesture drawings from Pelenakeke Brown, drawing with projections live. Inside the cube, Yo-Yo arches to the side, her arm over her head, shaping her body to the looping drawings on the screen. Behind her a description of the sound ‘birds leave sound gets deeper deeper steady rhythms are sounds like a train passing past far another like leaking rain.’

I think that translates to everything too, with social media, with communing on online spaces. We’re using these tools to present ourselves in a way that creates more possibilities. But there’s technocapitalism. I think there’s a hopeful side of me that’s like it’s so beautiful, but also it’s so scary because there’s so much money that goes into tech. Holding both of those truths together has been a big part of working within the digital media space.

Something you said earlier was having access to those tools has allowed you to explore different languages. How do you understand disability as language and how does that language apply to your process?

I think so much of my practice of the past few years has been trying to figure out what language. I have more illness and disability. I am figuring that out in ways that are not just words, but also visual languages, sonic languages, and spatial languages. I’m figuring out how those languages are connected to words. There are certain languages that are more readily received by certain groups of people. For example, when I’m talking to my parents, I can’t really use words to talk to them. I communicate through action. I need to communicate through visual language for them to understand where I’m coming from when it comes to disability. [Yo-Yo gestures both hands, with open palms and fingers splayed.]

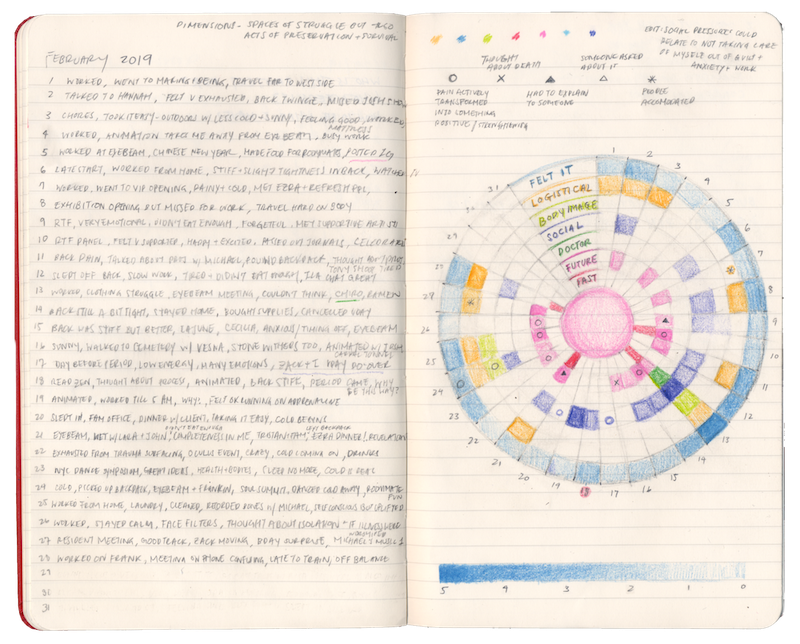

My parents and I don’t often talk about my disability experiences because I think we don’t really talk about things in general. [Yo-Yo laughs] It’s a cultural thing. It’s like as long as you are alive, then it’s good. We have food together; we talk about life. We don’t really go into the weeds of What is disability? and How are you doing with disability? If nothing is wrong, then you’re fine. When I started making work about my disability, I created the Resilience Journal. It is a way for me to hold space, witness, and be able to articulate the ways that my illness presented itself in daily life.

Image Description: Yo-Yo’s personal Resilience Journal open to the month of February. On the left side are a page full of notes numbered 1-28, the days of the month. On the right side is a circular visualization filled in with colored pencil, shades of blue, yellow, pink, green, red shaded in at various darkness levels, representing the intensity of the experience. The circle is divided up into 7 sections, or dimensions: 1. Felt it, 2. Logistical, 3. Body Image, 4. Social Pressures, 5. Doctor, 6. Future Visions, 7. Past Memories.

That was an interesting project because, over time, I realized that it was about building language. I had so little language for pain and so little language for disability experiences that I needed to literally track daily the different ways that it existed in my life to understand for myself, and to be able to share that with others. Because of the nature of my disability, one day I can barely be able to get out of bed or another day I’ll have some energy and be able to do things. Because my experiences vary so much, it was harder to translate that to something that people could understand as a way of being.

That was a tool that I created for myself that was helpful to share with my parents. It helped them see that this was a part of my life that I wanted acknowledged; it had not been acknowledged for so long. The journaling also became a way for me to come into disability community. There were moments where I was thought, Do I belong in disability community? because I didn’t have that language for my chronic illness experience.

There’s this thing that Simi Linton and Kevin Gotkin organized called DANT. It was essentially gathering a bunch of disabled folks who worked in the arts in New York City to have a bootcamp to learn more about disability. I almost didn’t even sign up for it. I thought, I don’t know if I belong in this space. Then my friend J. signed up and I said, Okay, I think I’ll go. I was the only person in the group that wasn’t sure about my disability status. That was wild to me because I didn’t think I was unique in that. As I grew older, my disability became less visible and more invisibilized. Once I started talking more about my illness experience, my illness became more legible to be in a group of people with experiences that resonated with mine. I realized we had a shared language.

Languages are ever shifting. They’re not ever one thing for everyone. In creating a language for myself, I was also hoping to create a shared language with other people. That is something that I’m still trying to figure out. [laughs]

How do you address burnout?

I actually started making work about my chronic [illness] experience because I was extremely burnt out and, again, I didn’t have the language to describe it. I didn’t know what burnout was. I was doing commercial work. I helped found a production company and I was the art director. I was in-house with my friends. I was working with different musicians and producing their live shows. It’s a really chaotic space to be in in general—the music industry—and on top of being a production house…it became too much. I was doing late nights, trying to do these tours. Everything was not well communicated or organized. Everything was very run and gun and fake it till you make it. Eventually, I admitted I don’t think that this is something that I can continue to do.

I ended up making a hard pivot. I didn’t enjoy what I was doing anymore. Having started this company with my friends, there’s this extremely hard dynamic where we’re both coworkers and also responsible for each other as friends/roommates. I lived with them for the first few years moving to New York.

I wanted to do the whole startup thing where I started this company, poured all of my energy into it, and, eventually, it’d be a self-sustaining company. Unfortunately, it wasn’t, even though we told ourselves this and told this to our clients. I think burnout has to do with lying. It involves lying to yourself and lying to other people that this is what you want and this is who you are. There’s something in the industries that I worked in that made it normal to lie about how you’re doing and how something’s going to appear. You act as if everything’s fine because that’s how work continues to get done. I realized that I couldn’t lie to myself anymore. I said, I’m not well. We’re not fine. This isn’t working. I felt like I was being dishonest to myself and I needed to figure out how to do work that felt honest to myself again.

So I left that heartbreakingly and then started journaling. Then there’s this thing called a Resilience Journal that I was making out of what felt like sheer necessity. I was doing this also because I ended up getting a residency at Eyebeam when they were still doing year long residencies. They gave people 25K for the year. I pitched the project to them saying I wanted to make work that specifically looks at creating my methodologies for reclaiming chronic health trauma. I said, ”Yeah, I know what this means,” but I didn’t at the time.

I was just saying things in a way that could make sense to someone else. Then I looked at what I was dealing with. Okay, here I am with all this burnout and feeling like I need to do something different. My body had never been in worse of a shape. The only way that I could see myself doing something again was literally looking at my day to day life, realizing my life as the work.

What’s just something someone told you about art, being an artist?

Nia Love is a dancer, a very beautiful person, who acts as one of the mentors at Brooklyn Arts Exchange. I’m paraphrasing but she said, “Making art is in the trade of hearts.” She said, “You’re really making things that are speaking from the heart to other hearts.” I had another teacher tell me this, too. She said, “When you’re making art, it’s also this present that you wrap up and you give to someone.”

Those are things that stuck to me. Nia told me this a few months ago, and this other teacher told me this years ago. I feel like those are things I wish I knew earlier on. Knowing how certain processes can feel so close to the heart and feel so sacred. This is where work comes from. It is very tenuous work because getting there is difficult. If I had known that starting out making art, I definitely would have tried to create as much as possible to get deeper into that space. Knowing what is the truth for myself within the work, to have a sense of groundedness and centeredness in how I want to create work, knowing what is honest, and what is authentic to myself.

So much of my artistic process has been realizing there’s so much that I want to unlearn about how I perceive myself, how I perceive what is possible, and what I think is worthwhile. Relearning to value things that are maybe softer, harder to describe, harder to pinpoint, and quieter. Oftentimes, those are the things that end up sticking with you.

Image Description: Spotlight overhead and surrounded by fragmented outlines of my body in white contour lines, Yo-Yo kneels on one knee and raises one hand towards the sky, grasping the tubes. She wears a design by Weijing Xiao, the metallic skirt around her legs glistening in the light.

Yo-Yo Lin Recommends:

E-Publication: Carolyn Lazard - The World is Unknown: I read and re-read this all the time. Carolyn unearths words where I thought there were none, for the body, pain, and the complexities of healing.

Podcast: Ocean Vuong - A Life Worthy of Our Breath: This episode with Ocean Vuong reminds me of the sacredness of language and the way we hold it in our bodies.

Artwork: Liu Yu - If Narratives Become The Great Flood: I saw this piece at the MoCA Taipei in September and it is mesmerizing. I love abstract storytelling with projections, and the music is immaculate. Liu Yu has such a gorgeous research-based storytelling practice.

Album: Pauline Oliveros - Deep Listening: I was introduced to this album by Petra Kuppers. This was an album recorded 45 feet deep into the earth. It has been hard for me to rest deeply, especially coming down from the adrenaline of performing at The Shed. This album put me into a restful trance that was very restorative.

TV Show: Extraordinary Attorney Woo - Currently watching this on Netflix and deeply enjoying the disability representation in this Korean drama. Though not without its issues, it’s very cute and funny and is some of the best-written television about disability experience I’ve seen so far. It’s awesome to see how popular this show has been in Asia and in the states.

- Name

- Yo-Yo Lin

- Vocation

- artist

Some Things

Pagination