On sticking with it

Prelude

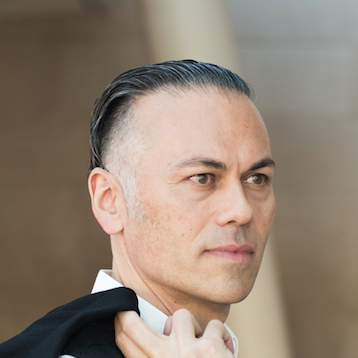

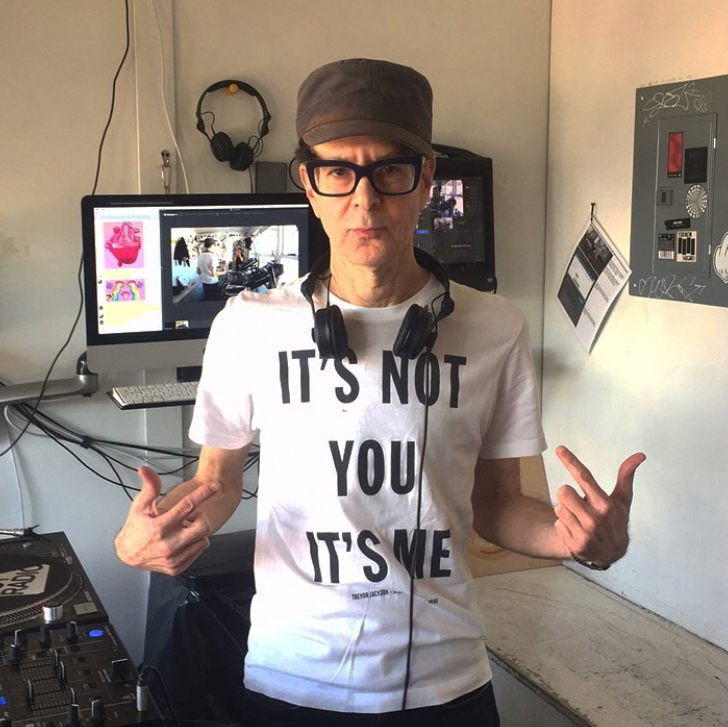

Justin Strauss’ power pop band Milk ‘N’ Cookies was signed to Island Records when he was 17, but he’s best known as a DJ and producer. Starting his DJ career three decades ago in 1980 at NYC’s Mudd Club, he has since established his own distinctive sound and become a sought-after remixer and producer, working with, among others, Depeche Mode, Sergio Mendez, Tina Turner, Jimmy Cliff, the B-52s, Luther Vandross, Malcolm McClaren, Skinny Puppy, and Goldfrapp, and appearing on more than 200 records. As half of the production duos, Whatever/Whatever and A/JUS/TED, he continues to produce and mix records, working on remixes for the likes of Hot Chip, William Onyeabor, LCD Soundsystem, Blood Orange, Holy Ghost!, and Beyoncé, and touring internationally as a DJ. Here he explains what it takes to keeps going in a longterm creative pursuit.

Conversation

On sticking with it

An interview with DJ and producer Justin Strauss

As told to Brandon Stosuy, 2791 words.

Tags: Music, Production, Process, Beginnings, Success, Independence.

How do you manage to have the energy to keep going? You’ve been DJing for three decades, and before that you were in the band Milk ‘N’ Cookies.

Music’s been my inspiration since I was seven. It’s all I wanted to do. I really didn’t know what else to do. I don’t think about it like “I gotta do it.” It’s very natural. I’ve never done drugs. I don’t drink. Music is what inspires me—to this day, I wake up and feel lucky to do something I love, and that people like it.

It’s not always easy, of course. Anyone who’s been in this business for 30 years knows there are downs and ups; it’s a rollercoaster. When I started playing, I DJ’d at the Mudd Club and the Ritz, the Tunnel, Limelight, and Area. I’d moved to California with Milk ‘N’ Cookies in late ‘77, ‘78, ‘79 and was around for the birth of the whole punk underground scene there. I’m sort of that guy in James Murphy’s song “Losing My Edge.” “I’ve been there, I was here…,” but I really was! I take inspiration from all of that. Being lucky enough to have been around all that and to drag it along with me. It’s a reference that not a lot of people have. To have actually spent every night at Paradise Garage, or going to see the New York Dolls, or just being in the right place at the right time and throwing myself into it, and being a part of it is something. I don’t take it for granted.

You shifted from making rock music to DJing. Why?

It’s just being a creative person. I grew up liking the Beatles and British Invasion and glam and New York Dolls and punk, but always liked James Brown and always liked disco and funk. When I heard Kraftwerk, it blew my mind. I never thought, “I’m gonna go from being in a rock and roll band to being a DJ.” I came of age as a DJ when there was all this amazing new wave, punk, rap, and leftfield disco coming out, then electronic music. So it was just new music, and we were just playing it. It’s being creative and being open to music. That’s always been my ethos for DJing. I play anything. There’s a flow to it, and it’s not just some mess, but it’s like connecting the dots for me. I can’t imagine liking one kind of music and nothing else.

Do you feel like you’re still learning things and still being surprised?

My sets are always a surprise; I never plan them out. If I’m doing a mix for a website or a DJ set, I try to think of the first record, or how I want to start the night, and after that, I don’t know where it will go.

Does new technology change the way you DJ and think about DJing?

I’d never DJ’d before my first job at the Mudd Club. I had a lot of records, and someone thought that I should try it. Milk ‘N’ Cookies had broken up and I didn’t know what I was going to do. I used to have my friends over and play records in my bedroom for them. I took that aesthetic to the Mudd club because I didn’t know anything else, and people seemed to like it.

Then I learned about mixing records and beat matching, and how that can elevate things. I met François K, who opened my mind to that, and took me to the Garage, and I heard Larry Levan, and became friends with him. That opened my world to a whole different thing.

The technology’s changed, but I keep it kind of like an old bag of records. I don’t use record box. I use CDJs with the USB stick. I keep it semi-random with a few folders here and there, just so I don’t end up playing the same stuff every night. It makes me think, and there’s times I can’t find something—it’s like back in the day when you’re looking for a record and you have two seconds left. It keeps it interesting. I do still bring a bag of vinyl with me, usually wherever I go, if they’re set up for it.

You come up with your sets on the spot. Do you ever find them going in the wrong direction?

I’ve been lucky. There’ve been sets where you’re like, “Shit, I could’ve been better,” but I’ve never felt, “Oh god, I totally blew it.” I feel like if I’m digging what’s happening, somebody else will dig it. I’m not so focused on watching the crowd, or seeing how they’re going to react to every record, and going from that, though. I have this inner thing, and I’m kind of shy about DJing, so I put my head down a lot. I get into my head. I know what I want to hear and it usually works.

For me the best thing is not to worry about, “Oh my god, they’re not reacting to this song.” I used to go to The Garage a lot. Larry would test out new records and people would clear the dance floor and stand there with their arms folded. But he would play it again and again and again until it was the biggest record at the club. You have to have that confidence in yourself to know, “This is a great song, and you’re going to like this at some point, and I’m just going to play it.”

For me, going out is going out to hear new music. I don’t want to hear a lot of things that I know. I want to be turned on to something new. One of the things that keeps me going is hearing a DJ and going, “What’s that?” I’ll go up to them and ask, “What is this?” I’ll be that guy, because I want to know. I’m still excited about hunting down a new track. I’m lucky to be friends with a lot of cool DJs and producers and we just trade stuff and share music.

808 State - "Pacific" Justin Strauss remix.

808 State - "Pacific" Justin Strauss remix.

There’s so much music coming at you from everywhere. I know people who’ve stopped DJing for a bit, and you get behind and miss things. It’s a lot of work: dealing with the constant promos, your friend’s sending you stuff… I still go to record stores, I still look on the sites that sell music. It’s all part of it. It takes up a lot of time, finding the music if you care about that, which you should, if you’re a DJ.

How do you decide if a song is something you can remix or not?

There’s got to be something on the record that inspires you. I’ve done so many different kinds of records, from Skinny Puppy to Luther Vandross to Depeche Mode to LCD Soundsystem. Back in the day, it was a different story because there was a lot of money involved in this end of it. The budgets were high because records actually sold.

People bought the 12”, and there was a reason for it. Now, the remixes are basically given away free. So there’s not that kind of budget. Although, in the past, we did have to pay studios, engineers, and editors because you couldn’t do it at home. These days the budgets are a lot smaller. If I hear a record I love, I’ll do it for free, basically. It’s a great way to keep you out there and keep you fresh and keep you in the mix.

It used be the total opposite. We used to make more money doing remixes and productions in the studio and DJing was just for fun. It’s totally changed around. Now it’s like, you don’t make barely any money, unless you’re lucky enough to get your track licensed on something, and you have some kind of deal with somebody who gives you some money. There’s more money in DJing now than making records. It’s become a much more profitable business to be a live DJ. That said, doing both helps increase your DJ fees because you’re more visible.

It’s a combination of things that will make me want to remix a song. I work with a partner Bryan Mette as Whatever/Whatever, doing remixes. I had another project, A/JUS/TED, with my friend Teddy Stuart. We did a bunch of things, originals with both of them, and remixes. I love the collaborative process, of working with other people, because, really, that’s how I started doing this. Not sitting in a room by myself with a laptop. It was going into studios, working with musicians, working with engineers, and working with editors, who I learned so much from.

When I do a remix, I don’t overthink it like, “What am I going to do with this?” It’s more organic. We start working on the drums, the bass, building up the rhythm, and then we see where it goes. Sometimes your have a vision in your head, of course, of how you want it to sound. Or a direction, or an inspiration, as to what the flavor of the mix will be. But, like DJing for me, I don’t know what’s gonna happen at the end of it: You walk into a club at night and you don’t know what’s going to happen. It could be a total disaster, or it could be the greatest night of your life. That’s the thrill of it all.

Do you you find yourself falling into any similar patterns with your remix work?

You try not to repeat, but as a remixer, there is a certain sound. Like a DJ, people like what you do, but you don’t want to play the same set. People trust their DJ. People have told me, whenever I saw Justin Strauss’ name on a remix, I picked it up. Which was very gratifying, as I would do the same for Shep Pettibone, Arthur Baker, Larry Levan, François K—all these people who inspired me. I knew it was going to be good. They had a certain quality to their productions that was something I connected to.

I think I’ve found a good way to fight that, by working with other people. One thing I like about collaborating is that I hear something one way, and the person I’m working with doesn’t hear it, or hears it another way. It’s going back and forth and trying to make that work. It keeps it fresh because somebody there’s going to say, “No, we’ve done that already. Let’s do something else.”

Goldfrapp "Anymore" Whatever/Whatever Remix by Justin Strauss & Bryan Mette.

Do you ever get pushback from the artist you’re remixing?

Oh yeah, especially when you’re working with a bigger act. I remember I did the Fine Young Cannibals’ “She Drives Me Crazy,” which was their first monster hit. They weren’t huge here and the label played me the song and I said that’s great, I’d love to remix it. The band hated it, but it went to Number 1 on the Billboard Charts, and the remix has kind of become a classic.

At that point, remixing was still a fairly new thing, and people didn’t get it. Like, “How dare you mess with my stuff, and my ideas.” My theory is that, and it’s always been that. It’s like, “Hey, your original is still there if anybody wants to play it, and this is for a club environment.”

Most of the time I’ve been fortunate, and people love what you do. But there have been those cases. Sinead O’Connor hated it. Red Hot Chili Peppers didn’t like it. They were anti-drum machines at the time. But the labels at that point were more powerful than the artists. So they would say, “We really like it and we think it could do well, and we’re putting it out.”

I’ve done some stuff where the artist or label didn’t like it, and it got shelved. That’s just the nature of the business. Some artists just didn’t dig it. But most of them have, and most people have written me saying, “I love what you did. Can I and get your drum track?” Like Skinny Puppy incorporated the remix into their live set. That’s happened before, and that’s rewarding.

Not everybody is gonna like what I do, or like me as a DJ. I’m not really looking to appeal to the whole wide world. I do what I do, and hopefully people like it. I’ve never changed to please other people. I want people to like it, but I don’t pander. I’d probably be making a lot more money and be a lot more successful if I did that. I’ve tried, and I just can’t do it.

Would you have any tips for someone who wants to do remixes? How do you stand out amongst all these remixes going up online everyday?

You have to do what you feel. My advice is try and be original in whatever way you can, which is hard right now. When I started this, no one wanted to be a DJ. Nobody wanted to be a remixer. I didn’t even want to. [laughs] It was just something that came along naturally, but kids go to school for this stuff now. It’s a very different thing.

Everything’s been done, but you still have to find a way. You have to find a way to put things that have been done together and then make it sound interesting. Bring your own spin to it. I think that’s what happens when somebody does break out—they’ve found a way to put a stamp on it that doesn’t sound like somebody else or does sound like somebody else, but is new in a weird way.

Every time I’ve done something with you, I’ve reached out to you directly.

I do everything myself now. I’ve worked with people over the years. In the ’80s I had big managers handling budgets and all this, but now I’m doing it. I wouldn’t mind working with someone who shared my vision and knew what I wanted to do. Finding the right person to represent you is the hardest thing. I don’t think anyone can represent you better than yourself. Plus, it’s super easy to book an airline ticket. You’re in direct contact with everyone and you know where you’re going to sit on the airplane.

Fine Young Cannibals "She Drive's Me Crazy" Justin Strauss Remix.

People reach out to me for gigs and people come to me and ask me to remix, or I’ll hear something and I’ll reach out. It’s a lot easier to get in touch with people now. Like, “Hey, I really like this.” If you don’t ask, nothing’s going to happen.

Of course, the business is not all ups. There was a time where I wasn’t DJing a lot and I was just in the studio and I missed DJing. I just asked, “Hey, can I play here?” Sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t. But more often than not, people said, “Yeah.” That’s how things get done. I always find that when you can reach out to someone directly and be in touch with them, it’s cool.

I wouldn’t mind working with someone who wants to help me move forward, but I’m okay doing it myself. I did have someone, but I was getting all the bookings and it just seemed like I was giving away my money to book an airline ticket. There’s many ways to book an airline ticket. So it was a practical move, as well, for me. But I’m open.

Justin Strauss Recommends

Inspirations : (in no particular order)

- Name

- Justin Strauss

- Vocation

- DJ, Producer

Some Things

Pagination