Kelani Nichole on pioneering a new type of gallery

Prelude

Kelani Nichole is a digital strategist and independent curator based in NYC. She founded and runs TRANSFER—an experimental, open-spirited gallery supporting artists with computer-based practices. Since 2013, she has worked to explore new modes of supporting and exhibiting “distributed” artworks (namely, artworks that exist in digital, networked, or virtual spaces). Here, she talks about building TRANSFER from the ground up, pioneering new models for collecting digital works, and why the “open sharing” is so crucial for artists with digitally based practices.

Conversation

Kelani Nichole on pioneering a new type of gallery

As told to Willa Köerner, 3043 words.

Tags: Art, Curation, Technology, Beginnings, Success, Production.

At the beginning, how did you get started with TRANSFER Gallery?

The idea for TRANSFER stemmed from a real need in the world, which I had seen during my time curating with a collective in Philadelphia called Little Berlin. At the same time—back in 2012—there was an article that came out in Artforum called “The Digital Divide,” by Claire Bishop, asking, “Whatever happened to digital art?” I felt like she was really missing something, and it suddenly seemed imperative to me to open up a space that would elevate the exploration of these kinds of emerging practices.

Around the same time, I was moving to New York City and thinking about what it would take to start my own exhibition space. I had been part of Little Berlin for three years. My curatorial career was very young, but I had found a specialty, and I wanted to continue supporting artists with computer-based practices. So, I started to look around for spaces. I was really lucky to find something very serendipitously on Craigslist—it’s actually the space that I’m still in today. That space really opened up the possibility of something like TRANSFER coming into the world. I still feel lucky to have found it.

At the same time, I was developing a career as a User Experience Strategist. I was making decent income, so I had a bit of money to invest—I had actually already been investing in studios that I really believed in when I was in Philly. So that was something that I knew I was interested in continuing to do. I also had a partner at the time who was also willing to jump in with me on this crazy experiment. So, I can’t say that there was a lot of foresight into what it meant to be opening a gallery focused on this kind of art. I think it was really an experiment stemming out of a desire to continue working with the studios that I had begun to support—and to deepen that support, in a new city, with a new format.

How did you figure out how to run a gallery, and what was that process like? Were there any resources you used, or did you just jump in and see what you needed as you went?

I knew a lot coming in, but the way I got those skills and that knowledge was quite unconventional. I never had any training within the commercial gallery context. I have no formal education in curatorial studies. The way I developed my practice was from a background working in technology, plus having an understanding of distributed practices, which are inherently the technologies that the artists I support work with.

But as far as the logistics of running a gallery, I developed those skills during my time in Philadelphia, working with Little Berlin. Little Berlin is a member-driven organization, and a totally experimental exhibition space. At the time, for maybe $50 a month, you could be part of the collective, and you’d get to have the space for a month out of the year. In that month, you had to do everything—from research, to finding a way to fund and install the work, to doing press, everything.

While I was a member, we did everything from finding a new space, renovating it, and building it completely out, to shifting the funding model and finding new ways to do programming. That experience really gave me the skills I needed to hit the ground running in New York City. Having that skill set—plus the professional skills around communications and experience design—is why TRANSFER has been successful.

Installation view, Ways of Something compiled by Lorna Mills, Episode #2 debut at TRANSFER, September 2014.

How have you balanced running TRANSFER with having a career as a user-experience strategist?

At this point they’re really interwoven, and necessary components of each other. For almost all five years that I’ve been running TRANSFER, I’ve been working full-time, either with a digital agency or with enterprise-scale clients. Continuing to do this kind of work is important to me for two reasons. For one, it keeps me grounded in the world of business, which is very different from the world of art. Because of this, I think I bring a sensibility to what I’m doing that’s a bit different from someone who’s only concerned with the economy of the art world and all that goes along with that.

The second thing is the financial autonomy that comes with having a sustainable source of income, which I can then invest in studio practices. It’s become something that looks a lot more like patronage than the typical gallery. After about the second year of running the gallery, I remember thinking, “What would it mean to make TRANSFER my full-time gig—to actually run a commercial gallery, and have a financial structure where whatever I was showing was also generating the income to sustain that activity?”

I found very quickly that that would require compromises that I wasn’t interested in making. Since the market for this work is still developing, and collectors are still just learning what it means to support these kinds of practices, it just wasn’t going to be viable. To this day, I don’t think it’s viable to run a really interesting, experimental media art space within the commercial art world. There are a lot of approaches out there that are interesting, but generally, they all seem to involve some sort of outside wealth coming in and supporting it.

That’s a good segue into my next question, which is about how you’re paving the way for more viable practices around collecting new media works. How have you approached selling artworks like GIFs, digital media installations, and other digital files/formats?

The activity in the gallery is never focused on selling, and I think that that’s what’s made it so successful. Ultimately, it’s been about educating people on the format of the work. There’s this tension between authenticity and scarcity, which I realized is at the crux of what I’m doing in making a market for some of these new formats. Things like animated GIFs are meant to live online—they’re very free, and when you think about restricting access to a GIF, that doesn’t make sense for the format. Plus, a lot of the studio practices I work with are based on open sharing and iterative development—putting out work to a community, and then having an open critique and dialogue with other artists.

So acknowledging that as part of placing a work has been really important. More and more, collectors are starting to understand this distinction, and are getting more interested in investing in a work. This discussion of new formats is something that’s decades old in the art world. Conceptual art has had a market and has even been traded on the secondary market for a few decades now. For me, it’s more about making a case for these kinds of new technologies, and why it’s culturally significant and critical that these types of works are collected and preserved.

I tend to have this attitude of, “They’ll come when they’re ready for it.” I don’t need to go out and sell anyone an idea—either you get it, or you don’t. With the kind of computer-based work I’m supporting, I’ve realized more and more that there’s this whole group of people who “get it,” but who don’t understand what it means to buy art. They understand what the work is about, they understand the need for openness, and they understand the formats—but they don’t know what it means to fall in love with a work of art. What I want to evolve into as a gallerist is someone who can engage my peers who are working in technology and finance. These young professionals don’t have a true love for art yet, and finding a way to introduce them to that has the potential to create a new generation of patrons.

The Current Museum has been my first project where I’m able to bring both of my skill sets together in a very real way. I’ve been doing experience design for it for the past few months, taking it through the same process that I take my clients through: looking at the landscape, taking in learnings, and then developing a model around the real need in the world. So I think that that project, for me, feels like the new frontier.

Installation view, Sweet! Finances from Claudia Maté at TRANSFER, July 2014.

Can you share how you go about discovering the artists that you go on to represent and work with?

Almost everyone I work with I first met on the internet, or through one the artists I already work with. But—and this is a really important point about TRANSFER—I don’t represent individual artists. I feel like the general structure of representation that the art world is built upon is toxic to artists, and not good for supporting their practices. So I’ve always thought more about supporting a community of practitioners, and not “representing artists” in the traditional sense. The artists I work with are totally free to have relationships with other galleries, institutions, whoever they want. In short, they really have the reins of their own career—and, actually, that’s the number one thing I look for in an artist.

Almost every artist I work with has a commercial practice—whether it’s in education, technology, or something else—that’s adjacent to their work, and that’s essential in helping them maintain a vibrant relationship to their studio practice. I think it’s important for an artist to have a job, because the romantic idea of the artist in the studio who’s detached from the realities of contemporary society is, I think, a really dangerous myth. What I do isn’t the sort of thing where you work with TRANSFER and now suddenly you’re a full-time artist and you don’t have to worry about anything else.

What TRANSFER’s community of artists does is create an environment where these studios can work together in a network, sharing very openly. They may share works in development or offer each other critique, but generally they’re offering each other resources. This community of support is really the success of TRANSFER. As one example, there’s no PR budget for any of my exhibitions—it’s just myself and my artists putting out the word about these shows. We manage all communications together, and because of this, we’re able to create a very genuine connection with patrons. In this way, TRANSFER is built on relationships, which are the true mechanism of amplification on the internet.

This networked approach is how I find new artists as well. I watch and see what my artists are doing—who they’re collaborating with, who they’re sharing ideas with, and who’s influencing them. Also, for me, one of the most important things to keep an eye on is the diversity of artists within my program. It’s something I feel I’ve managed to be pretty successful at—sort of pushing the identity of what a TRANSFER artist can be, and having that be a very non-exclusive and nimble thing.

How do you plan out the exhibition schedule for TRANSFER? Do you have a whole strategy around it, or do you take it month by month?

I typically set the gallery’s program a year in advance. I’ll say to myself, “What do I want from this year?” I like to think about what I want to achieve, and what I can do for the studios—taking a look at who needs what—and also, on an ongoing basis, taking feedback from folks. This year, I’m setting a very different program. I’m actually stepping away from programming my Brooklyn space and handing the keys over to other curators. I want TRANSFER to become a bit more of a platform that others can use to explore their own ideas. I want to find new ways to bring in more people who are supporting emerging practices, and to align myself and my space with them. So, that’s my goal for 2018.

Installation view, Precarious Inhabitants from Eva Papamargariti at TRANSFER, May 2017.

Are there things you see a lot of artists doing that you wish they wouldn’t do? Perhaps some common pitfalls you tend to see artists sucked into, over and over again?

There are a lot of artists working with distributed practices—artists working in new mediums, and using the web as a medium—who start to find success in the commercial art world, and remove their practice from the internet. That to me is really sad, but I can’t tell anyone that they shouldn’t do that, because they’re obviously getting that advice from commercial agents telling them that’s the best way to sustain their practice. I think that’s a shame, but that’s just my own perspective.

For my artists, I encourage open sharing as a rule, because I think it’s a really crucial part of new-media practices. There’s a big difference between open sharing and free labor. The idea of what it could mean to generate revenue from a studio practice—how an artist might leverage their practice to make money through the internet—is a very interesting one. I don’t think anyone’s quite cracked it yet.

One common pitfall I see in my own community of artists relates to overproduction. Inherently, the iterative nature of the web can lead to over-producing. This can distract focus from the studio, so it’s one thing that I always try and advise my artists around. That being said, if you can jump in and make a quick GIF and be a part of a group show, or be part of a dialogue that’s really pivotal in one moment, then that’s great. Somewhere there’s a balance in there.

For the past few years, TRANSFER has been focused on showing work by women artists. Can you talk about how you made that decision, and what it’s been like?

When I was in that yearly process of evaluating what TRANSFER could and should be, I took a look at the gender balance in my program. This led me to realize that I actually had more men in my program than women. After seeing this, I challenged myself to focus my energy on making solo shows with women artists for a year. In that year, the result was more powerful, challenging, interesting, and just overall more meaningful than anything I had previously done. So I just kept doing it. Since then, I’ve only been producing solo shows in the gallery with women artists.

I still find other ways to engage the men in my roster, through (for example) fairs or other kinds of alternative exhibitions. But overall, the focus on women has been really crucial, and has brought new perspectives in that I might not have found otherwise. Part of opening up the space to other collaborators this coming year is to say, “I don’t think TRANSFER can represent as diverse of a perspective if it’s curated just by me, than it could if I just give the opportunity to program the space to others.” So I really want to keep opening up the program in that way. Not in a forced or prescribed way, but in a way where I can see where it goes, and see what this offer of openness can activate in the world.

Kelani Nichole recommends five artworks for anyone interested in starting a collection of emerging contemporary art for under $5K:

Faith Holland Visual Orgasms animated GIFs

Waterfalls (2013) – Animated GIF 1000x667px/20 Frames, 2013. Edition 5 + 1AP.

What it is: Excessive moving image collages that depict metaphors for orgasm with no actual depiction of sex.

What you get: Animated GIF delivered on USB along with a still print and signed certificate from the artist.

Carla Gannis Hell Panel Archival Digital Print

Hell Panel (2013) from 'The Garden of Emoji Delights' series, archival digital print 8.5" x 21". Edition of 20 + 1AP.

What it is: A full-scale reimagining of Hieronymous Bosch’s iconic altarpiece, in print, animation, and augmented reality. The work re-inscribes Bosch’s triptych using pop vocabulary of signs, digital symbols, and Emoji.

What you get: A signed and numbered print, ready for framing.

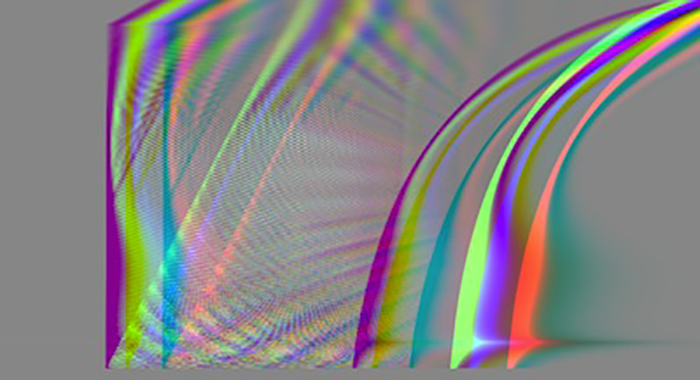

Daniel Temkin Glitchometry

Glitchometry #7 (2011) – Archival print on transparency, installed in a lightbox frame measuring 16" x 30". Edition of 7 + 2AP.

What it is: Algorithms designed for sound editing are set loose on images, twisting the data into strange new patterns. Each image begins as a simple black and white geometric shape—such as triangles, in the case of this image.

What you get: Archival digital print mounted and prepared in a backlit LED lightbox frame, along with a signed certificate from the artist.

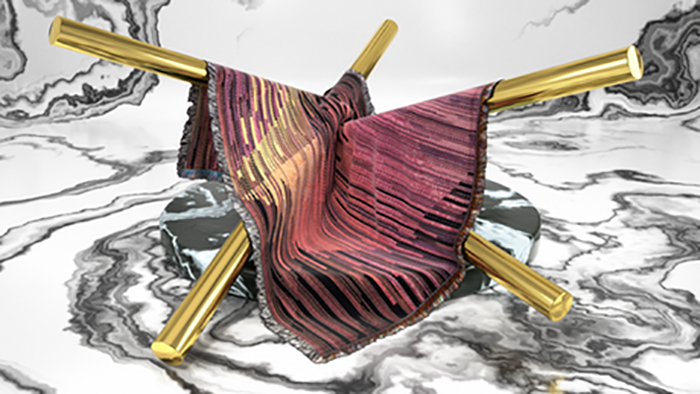

Phillip David Stearns Glitch Textiles

Glitch Textiles (2013 – Ongoing) – Blankets, pillows, scarves and custom textiles from the studio of Phillip David Stearns.

What it is: Unlimited-run artist-edition home decor objects and custom textiles that “render the subtle structures of our digital reality into intimate, tactile materials.” The design approach is an expression of the abstract and invisible language of digital technologies.

What you get: Pillows, scarves, laptop sleeves and more. Order online from the artist’s studio.

Claudia Hart The Flower Matrix

The Flower Matrix (2013-ongoing) – Decor in large editions from Claudia Hart's mixed-reality chamber (on view at Gallery 151 in Chelsea through January 28th, 2018)

What it is: Psychedelic, functional art objects embellished with decorative elements illustrating an aesthetic in which technology has replaced nature—sugary sweet and chemically toxic in equal measures.

What you get: Beanbag pouf, ceramic tea sets, platters, and plates in limited artist editions, along with a signed certificate from the artist. Augmented-reality moving images can be viewed with the layar app.

- Name

- Kelani Nichole

- Vocation

- Curator, Gallerist, Digital Strategist

Some Things

Pagination