On overcoming the anxiety of making creative work

Prelude

Conversation

On overcoming the anxiety of making creative work

Poet Layli Long Soldier discusses poetry as prayer, trusting in the unseen, and how dreams can be a powerful creative tool.

As told to Brandon Stosuy, 2189 words.

Tags: Poetry, Anxiety, Process.

How do you go about writing poems with prayer in mind?

When I talk about the poem as prayer, I mean it in the sense of process. I don’t know where to begin, but before I do share anything, I want to say it’s a risk for me to talk about things in this way, only because I don’t want to sound like I’m on some path forging new ground. This is ground that has already been covered. I don’t want to come off like a guru or something.

Prayer is something I’ve been thinking about recently… in many ways. Prayer in its many version and applications. Maybe one of the things I’ve been thinking about is some of my friends in Standing Rock, for example, and the community there, how they insisted on prayer as being the primary tool for resistance. That was central to everything they did. It really made me think about that energy, that force, and what happens when we utilize it.

I have also just been thinking about prayer in terms of my own process, which I think has always been there. I never really articulated it, so I don’t know where to begin. Maybe you can help me.

When you’re writing a poem, do you have this idea of prayer in mind? Do you see the poem itself as some sort of “sacred text”?

Actually, no. I don’t necessarily sit down and think, “Okay, this poem is going to be a prayer, or should be utilized that way,” but I do think that when I begin writing. It’s a part of my process. What I want to say is, maybe, being in a state of prayer as I write. I’ve heard this from other writers. When they sit down to write, sometimes they’re terrified because we sit down, we know we’ve written poems before, but every time we sit down to write again, we don’t know if we can do it again. We don’t know if we can do it well.

There’s a real vulnerability in that, a fear, and a threshold you have to cross. At least for me—I’ll speak for myself—I have to acknowledge that trepidation, that anxiety in myself. I think it’s at the very beginning point, in that vulnerability, where I have to begin to reach outward or rely on something else, not just of myself. That’s what I mean when I say prayer is a part of my process.

Also, in writing or creating or making something, there’s this process of accessing and relying upon the unseen. Again, I don’t mean that in sort of this esoteric mystical way. I just mean even in ourselves, we are relying upon our minds and our imagination. Those are things we can’t see. There’s a sense of trust that we build within ourselves with the unseen. At the same time, I feel again, there’s this thing outside of myself: I don’t necessarily myself feel always capable of writing something “good,” you know?

Whatever it is out there that’s bigger than I am, that energy, can you help me out? Just help me out this evening as I sit down, and let’s see what we can do. I’m willing to be helped.

How do you tap into that in the process when writing, of reaching out and finding that space?

There are a few things, even in the practical things I do. I’ll mention just briefly the idea of ceremony. I don’t mean ceremony that people just makeup, but traditional ceremony. There are certain things that you do that are in place to put you in that state of prayer, physical things. There are times of year for certain ceremonies, or what have you.

Just as a parallel, I’d even say for myself there are certain things I do. Maybe they’re just cheesy. But for example, my working hours are usually very late at night. Most of my poems have been written, I’d say between 10pm and four or five am. For me, there’s something about the night that’s very helpful. First of all, it provides a stretch of time, a block of time where there’s not a lot of distraction. In order for me to think things through, I need that.

There’s also something about nighttime in the sense that you’re tired. When you get to that place of being tired, certain layers are stripped off and start to fall away. I find myself beginning to open up to things that I’m not necessarily going open to during the day, when I’m running around and taking care of practical things. That’s part of my practice, to help me access that place.

Craft is a way, too. We need tools. We need things. Language is immaterial, but it’s through certain devices or tools that we have in working with the language that I think, magically or miraculously, help me access that place as well.

Do you write at night when you have a manuscript in mind? Or is it something you do on a regular basis, no matter what?

It’s like that all the time. I used to actually blame it on my daughter. I’d say, “Oh, it’s because I have a child, so that’s the only time I can find to write.” But I had a residency awhile back, and I had time to myself without her. It was just my thing, about 10 o’clock, I would crank up the coffee machine and set to work. Some of my peers would kind of scrunch their brows at me like, “What are you doing?” But, yeah, it’s something I do all the time, it doesn’t always have to do with a project or a larger manuscript.

When you say that words are immaterial, what sort of more material things do you pull from to help you kind of harness the words?

Well, there are a few things. Sometimes I work with Lakota language in my poems, and that is always a beautiful source for me to turn to. I use Lakota dictionaries, but I also ask people how to say certain things. You know, I have conversations about our language with others. I think sometimes that even just one word can propel me into a thread that I might follow through on in a poem. I also think I’m always listening and collecting language, just English language.

Sometimes I’m pressed for time and I can’t sit down and meditate for hours and hours. I will keep a running journal, for example, a little notebook of language that I encounter throughout the day—things I hear people say or little turns in phrase that are interesting. Then at the end of the day, I’ll sit down and type those out. I see that like a palette of paint. I have a palette, or color scheme in mind. You know, as a painter, you might set out colors and think, “I’m going to work with this today.” I’ll do that with my journal: “This is what I have encountered today. Let’s see what happens when I put them on the page. What are those connections and how can I work with them?”

You clearly have a specific process. Do you still find moments when you try to write and can’t get past a creative block, even using your techniques?

For sure. I think that’s why I also work in other mediums. Sometimes I have the urge to make something. Sometimes I want to make a poem but at that moment I can’t for whatever reason, so I work with other materials. I like to do sculpture; my sculptures are usually more like objects. I also play music here and there, but I just do these things to kind of help me with writing… I use these other ways of making to help keep my wheels moving in one way or another, and eventually the language will come for writing. Sometimes I do get writer’s block, but I have never really viewed it in that way. I still try to make things even if I don’t have the language or words to put to it in at the moment.

I’ll give you an example. I’m participating in a exhibit in Montreal, and I’m leaving on Friday. I’m going up to there, setting up some of my work. The exhibit is called Drawing a Line from January to December.

I was talking to another artist, Tanya Lukin Linklater–she’s an Alutiiq artist from Alaska, and she invited me to participate. They were interested in me contributing text, but when we were brainstorming about what I might do for the show, all I could think of was making boxes at the time, which was really funny, like physically making boxes, which was not really what they were asking for. I said to her, “You know, I’m not sure what I’m going to do, but this is where I’m starting from. I want to do some boxes, but I’ll certainly develop text to go with it as well.”

In the end I did work on three boxes, which was my initial impulse. I have no idea why I just had to make these things, but in the end I made three 10-inch by 10-inch boxes out of balsa wood.

I was reading this poem by C.D. Wright in her book One with Others. There’s this little line that she has that says, “There is sanctuary in the mind made of balsa and glue.” It’s so funny. I read that today.

After you made the boxes, did you end up writing the text to go with it?

Yes. This is what’s crazy. I don’t know how this all came together, but it all came together. It’s a yearlong show. For all of the artists contributing work, there seemed to be a connection in our work that had to do with loss or grief. It made sense because winter is a time for thinking about some of those things, this idea of loss. I was meditating on that theme, on that subject.

In this last year I’ve had a number of losses. I had a relationship end, a breakup that was very difficult. I also lost my grandma on my dad’s side, and I lost one of my cousins in a very sad, tragic way. All these things happened sort of back to back in the last few months, and so it was something that was really on my mind.

I tried a whole bunch of different versions of text and different kinds of poems, and they didn’t seem to feel right.

I ended up writing a poem about my grandmother. The thing a poem is, how does it go? “What a poem is about is not what the poem’s about,” right?

In any case, I had this dream. I said a prayer. I was praying, talking to my grandma one night before I went to bed. Then I had a dream—I woke up to this dream that same night. In that dream, I was teaching an art class. One of my students was selling sheets of balsa wood of all things. They were $12 each. I said, “Oh, I want to buy some balsa wood from you. I want to buy some sheets. I need some balsa wood.”

I reached into my pocket and I said, “I want two sheets.” I reached into my pocket and I only had enough money for one. I had $16, not 12. I said, “Oh, I only have enough for one sheet.” Then my student said, “No, you can keep them both, teacher.” It was such a kind, generous act. I woke up and wrote down this dream. Then I wrote down the things I had been talking to my grandmother about.

Really, what I had been asking her was questions about love, about relationships. One of my main questions was, am I enough for someone? Of course, in a breakup, these are things we wonder… like, “What happened? What’s wrong with me?” and so on. I was sitting there in bed crying to my grandma, “How come I can’t find love? I’m not enough,” all this.

I showed what I wrote to a friend and he said, “My goodness, Layli, do you see what I see?” I was like, “What? What are you talking about?” He said, “You know, you asked if you’re enough and then in your dream even though you only had enough money for one sheet, it was enough for your student. It was enough.”

It was right there in black and white, in the text, this connection that even I had missed as the writer. I was like, “Oh my god, how did that work?”

Suddenly it was this piece about my grandma and the boxes that I was so motivated to create, and I didn’t know why. It all came together.

Layli Long Soldier recommends:

I don’t have 5 things. I have only 1 right now… Prayer.

- Name

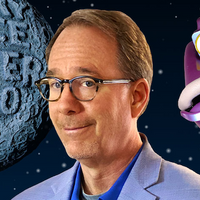

- Layli Long Soldier

- Vocation

- Poet

- Fact

- Layli Long Soldier is an Oglala Lakota poet, writer, and artist. She's served as a contributing editor to Drunken Boat. She was awarded the Lannan Literary Award for poetry in 2015 along with a National Artist Fellowship from the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation. Her first poetry chapbook was Chromosomory (Q Ave Press, 2010). Her first book, Whereas, is being published on March 7, 2017 by Graywolf Press.

Some Things

Pagination