Lisa Yuskavage on trusting your creative instincts

Prelude

Conversation

Lisa Yuskavage on trusting your creative instincts

As told to T. Cole Rachel, 3176 words.

Tags: Art, Painting, Process, Inspiration, Independence, Anxiety.

Your work is fascinating in that it invites so many different kinds of interpretation and simultaneously seems to deflect them. Do people constantly want you to explain your work? And does the idea of interpretation interest you?

In the beginning of my career, some people really demanded it. Like they kind of came at me. I literally almost felt like they were going to beat me up if I didn’t help them, if I didn’t explain myself or at least give them some direction. I have always just flat-out refused.

The funny thing is, over the years I’ve given talks on my work and people are always surprised when I spend most of the time talking about process and form. I’m still curious about my own motivations and I can talk about why I chose to do something at a given time in my life, I could ruminate on why I might have done this or that, but it’s not about explaining what the work means. Also, I haven’t gotten to use this as much as I would like to, but when somebody says something critical and unpleasant about my work I often respond, “You say that like it’s a bad thing!” There’s so much possibility in that.

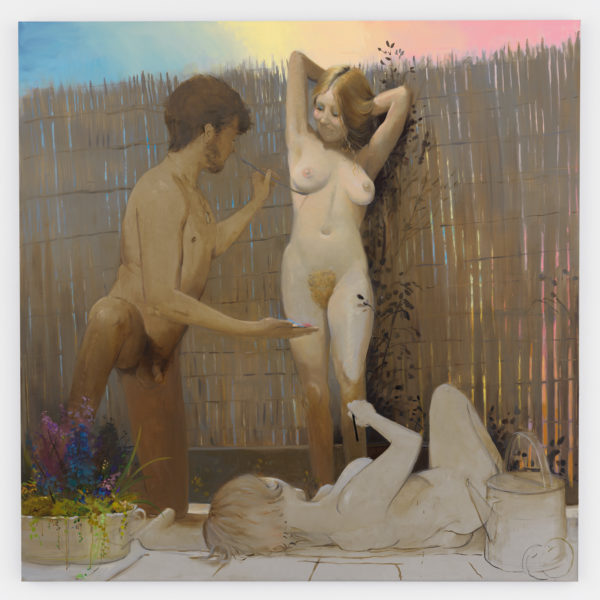

Déjà Vu, 2017. Oil on linen. 80 x 80 inches

In the early ’90s, when I first started showing these paintings of nude females, apparently that wasn’t really done by a non-academic artist. Most early viewers were sort of like, “Why would you want to do something like that?” I got the wildest reactions. I remember being at NYU about to give a lecture. No one really knew what I looked like or recognized me and I was standing there listening to a bunch of girls who were looking at the paintings and saying, “You know, she’d better be gay,” I felt kind of like, “Whoa, shit.” It was so aggressive. It was like people were always looking for the exact smoking gun. They needed or wanted me to be a certain way, to represent a certain thing, in order to make sense of the work in a way that felt OK for them. They were more obsessed with why the work was made than by the work itself. It was like someone digging through Nabokov’s biography trying to find out why in the hell would he write Lolita instead of being able to just be happy that he did.

Aside from, say, going to art school to study painting and art history, what do you think of as being the most valuable kinds of training you had for being a painter?

When I went to college I made it a point to go and study abroad for a year, to go and immerse myself in art and travel around Europe. Wild horses could not have kept me from doing that. When I was there it was the happiest I had ever been in my life. I did not want to come back. I remember really struggling to figure out, “How do I go back to my old life now that I’ve been exposed to all of this beauty?” When I came back to Philadelphia I remember being shocked at how ugly it was where I lived. (laughs)

That experience of really studying and immersing myself in all of this classic work, just wanting so badly to see all of these things in person, to understand this different world… it was so important. Prior to that, I never really felt like I fit in. It wasn’t like I didn’t fit in most ways—I wasn’t a minority, I wasn’t gay, I wasn’t an outsider in any traditional sense, but I had this overwhelming feeling of being out of place and I couldn’t really figure out what the nature of that outsiderness was.

The Art Students, 2017. Oil and charcoal on linen. 80 x 80 1/8 inches

It wasn’t until I became an artist that I could finally understand that this was what I’d been missing. These people and this conversation. Other artists. It didn’t matter where you lived or what kind of ugly place it was because the art gave you a place to go, to escape. You discover friends everywhere you go because you are like-minded in this way that’s really important to you. It is in some ways it was like coming out of a closet. The more artists I met, the more I felt like I’d just finally found my people. Something finally fell into place. I think about that now anytime that the business of being a working artist becomes difficult or unpleasant. There is this other side that always makes it worth it. I get to live this life and meet the kind of people I would have never known had I not been an artist.

There is a specific aesthetic and real clarity of vision to your work that is unmistakable. How do you maintain that? How do you avoid getting stuck?

We are often standing in our own way. You can point the finger at that person who doesn’t like you or that teacher who keeps thinking you’re doing the wrong thing, but who’s really here that’s tripping you up? We tend to trip ourselves up. I’ve seen that with students and I’ve certainly felt it many, many times in my own life. I’ve managed to get completely lost and have struggled to get out of that.

There have been those moments of feeling like, “How did I get back to this? What did I do wrong? How did I get in my own way again? What did I do? How did it happen?” When I felt that the most profoundly, I just started to read. I spent a lot of time in libraries because I knew that I wasn’t going to paint my way out of it. It was a mental problem. It was a thinking problem. So I started reading a lot about other artists. Something about another artist’s experience can really help.

There were two things that I came across. One was a Diane Arbus book. The other was Philip Guston’s writings. In both cases, the idea of not pointing the finger outward but looking inward and putting oneself in the position of being wrong was really important. Recognizing yourself as being the bad guy, in a sense. I thought about that a lot over the years.

I’ve gone through many, many bodies of work and have learned something important from all of them. I remember once feeling very stuck and having to sort of jar myself forward by just trying to essentialize. I would ask myself, “What do you really want to do? Stop fucking around. Paint like you only have two more days.” Not that you’d be dead in two days, because that might feel better, but imagine that you only have two more days and then you’re going to go back to being stuck in a normal life where you don’t get to paint. That would be the hell. Imagine painting gets taken away from you completely. You don’t get to be an artist. So paint like that. You paint like you’re saving yourself. You’re fighting for air. You’re going up to the top just to grab some air before you go back down again.

Hippie (Nude Bra), 2016. Oil and graphite on linen. 48 x 40 inches

When you have one of these moments of pause, whether it’s after a big show or when you find yourself ready to embark on a new body of work and move into the unknown, how do you ward off panic? How do you negotiate the feelings involved in starting something new?

I recently woke up one morning at 4am and was like, “Shit. I’m awake. I could go to the gym, but that would turn me into a person I don’t recognize—a person that gets to the gym at 5am. So I’m going to sit here and wait for it to become 9am.” Not knowing what to do with myself, I started looking through the archives on my website where we’ve been working towards organizing all the existing data there is out there that’s related to my work. I was looking at all of these old lectures that I’ve given and there was one that I didn’t remember at all.

So I started watching it. An old friend gives me a very nice introduction and then I come onstage and start talking. I was really surprised, while watching it, that I actually liked what I said. I basically went onstage and talked about feeling like a fraud. I spoke about wanting to come clean to the audience that, in that moment, I was feeling very inept and had no idea what I was doing. I felt like I needed to get that off of my chest before I could continue with the lecture. At the end there is a Q&A and I mention that I had just started working on something that I was getting kind of excited about but I wasn’t really sure if it was gonna turn into anything.

I start to wonder what painting it was that I could have been talking about. I figured out that it’s this painting called Triptych, which is a painting of a woman who is viewed kind of splayed out on a bench. It was something I did a while back, a big green painting. I think it was probably one of the most important paintings I ever made. In that lecture I’m also saying that the only thing that’s keeping me from total panic and a total freakout is the knowledge that this has happened over and over again and that I have been here before. I’m saying this not knowing that I’m about to make one of the most important paintings of my career.

Right now, in 2017, I’m about to move into that same state again. I’m not quite there yet, but I will be soon. I just finished a big body of work and my studio is basically empty. A painter friend told me that you should always leave at least one unfinished painting behind. It’s like a safety net, so you have something left to work with. Of course, me being me, I want the studio empty. I like for it to be really hard. I like to have no safety.

Your work says so much about intimacy. Not just emotional intimacy, but physical intimacy that is sexual but not necessarily always about sex itself. That is such a complicated state of being to try and visually unpack.

Yes, because it’s neither here nor there, you know? It’s actually one of the great states. One of the great places to be. That was the thing that was so wonderful about making these most recent paintings. Now, as I think about moving into a new body of work and asking myself how to keep going, I’m just focused on trying to be super clear about what I enjoy. Where is the location of joy in the work? What is the best part? Then, get rid of the rest.

What came to me in the recent work was the idea of couples. Not only were they the perfect vehicles for these paintings, but more importantly, I really enjoyed their presence. It was so important. There was a painting in the last show called The Neighbors with a woman standing over her partner—husband, whatever. She’s straddling him and he’s looking up. It’s playful. He’s enjoying her, and she’s enjoying him, and it’s complicated.

Wine and Cheese, 2017. Oil on linen. 77 1/2 x 50 1/8 inches

The idea of making paintings of people who were being warm towards each other felt good. It felt like something I’m not sure I’ve ever seen in paintings, a heterosexual couple not being sexual but just being physical and loving. I just love the intimacy of bodies and I’ve always been kind of interested in what can I make a painting of that I haven’t quite seen before.

One thing that I suspect sometimes—particularly from those who might look at my paintings and say that they are not “serious” art—is that there are people who are probably a little jealous that I’m having a hell of a good time doing this. I really enjoy it. I know I’m not doing bad paintings when I’m enjoying them a lot. The most important signal to me that something is working is when it can make me laugh or make me overwhelmed with emotion. I look at the girl in this painting across from me and I just really like her. She makes me feel good. I really want to be in her company. Sometimes it’s as simple as that.

I remember when I had an exhibition in the early ’90s, back when I was a young artist, and a guy from the gallery came into the studio to see what I was working on. My work had shifted during that time, I had gone from doing my “Bad Babies” paintings and was also doing these little sculptures and maquettes. I was really enjoying myself with that work, so I knew it was right. When I’m happy and I’m enjoying it, you could give me 1,000 lousy reviews and I’ll still know that it’s going to be OK. I mean, I did get a 1,000 lousy reviews sometimes and as still like, “You know what? This is going to be okay.” That has always been right. That hunch. That feeling. It’s “I’m right and you’re wrong,” and there’s no two ways around it.

So this guy comes up to visit me and he looks at the work and is like, “This is not the show you promised us. This isn’t what we wanted.” I was like, “Well, I guess you’re not doing the show then. You’re telling me you’re not liking this, so what are you saying to me? Are you suggesting I should back up?”

It’s like when you’re running the bases in baseball. You don’t want somebody to back up. You have momentum. You keep going. Don’t tell me to back up. It’s always been amazing to me that there are people out there who want you to be stuck, people who can’t stand it if you do what you want. You can’t fucking listen to that. I think that that’s super, super, super key for young artists to hear. You have to just shut them out, you know? When I was in my 30s I would get upset at things like that, but now I just laugh. I’m like, “Seriously? You want me to go backwards? You’re getting in the way of history. My history!”

Paying too much attention to those outside voices can wreak havoc on your work if you aren’t careful.

I just think of all that things that would not have happened if I had listened to that motherfucker. I was like, “Dude, cancel the show if you want, but I’m not going back.” Of course, after he left I probably cried and cursed. I probably felt sorry for myself and then doubted myself for like an hour. Then, thankfully, I got back to work. I couldn’t go backwards. I had nowhere else to go. I had nothing else to do. That was it. I was in it, so I was like, “You know what? If this sucks and I’m going down with it, that’s all I got.” Sometimes there is no parachuting out. There’s only forward.

Ludlow Street, 2017. Oil on linen. 77 1/4 x 65 inches

A show of Lisa Yuskavage’s most recent paintings is currently on view at David Zwirner gallery in London.

All images courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London.

Lisa Yuskavage recommends:

-

David Sedaris’ new book, Theft by Finding, and his recent interview with Terry Gross. I listened while jogging in Central Park and was very engrossed (not to make a bad pun).

-

My father-in-law, Victor Levenstein, recently stood up (at the age of 94) and told his harrowing and amazing story of surviving KGB torture and the gulags. You can hear it on the Moth Podcast.

-

The Prado Museum in Madrid, especially to see Velázquez`s Las Meninas. If you can’t get there soon and reproductions are not enough, I loved this amazing short film by Eve Sussman called 89 Seconds at Alcázar. (A little piece of IMDb trivia: Peter Dinklage is one of the cast members.)

-

Merlin’s KIDS is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing individually trained service dogs to those in need. They rely solely on charitable donations to achieve this goal. Janice Wolfe, canine expert and founder of Merlin’s KIDS transforms the lives of dogs by rescuing them from shelters, training them and giving them a very meaningful purpose to their lives. These special dogs in turn help transform the lives of both the children and the adults they serve with a life long commitment to love, care for and assist. So in essence, the dogs save the kids and the kids save the dogs. It’s a match made in heaven! My personal favorite duo‚ who are being trained to work with veterans, are chihuahua brothers Lt. Dan and Taz. Donate here.

-

Private Life is an upcoming film by written and directed by Tamara Jenkins to be released this fall. I got a sneak peek. It is extraordinary and original and funny. Starring Paul Giamatti and Kathryn Hahn. There is a line in it where Paul says to his wife, “Shall we take down the Lisa Yuskavage!??” I am so proud to be a part of this incredible filmmaker’s work.

-

I am a Marcia Hall super fan. Her book Color and Meaning: Practice and Theory in Renaissance Painting was a game changer for me. Over this past year I was in touch with her and asked if she was writing any new books and if I could be one of her advanced readers. She very kindly sent me pages from her forthcoming book Color. Materials. Making. Marketing. Meanings, which covers the art of the 15th century up to World War I. It is fantastic. Painters are in for a treat.

- Name

- Lisa Yuskavage

- Vocation

- Artist

- Fact

- Widely associated with a re-emergence of the figurative in contemporary painting, Lisa Yuskavage has developed her own genre of portraiture in which lavish, erotic, vulgar, angelic women (and more recently men) are cast within fantastical landscapes or dramatically lit interiors. Seamlessly blending pop cultural imagery, color theory, and psychology, Yuskavage draws on classical and modern painterly techniques and, in particular, marshals color as a conduit for complex psychological constructs. When asked about working through difficult periods in her career or confronting creative blocks, Yuskavage offers the following: “You paint like you're saving yourself. You're fighting for air. You're going up to the top just to grab some air before you go back down again.”

Some Things

Pagination