On multitasking, craftsmanship, and letting go of your work

Prelude

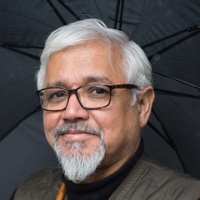

Jacob Bannon is a musician and visual artist best known as the vocalist of Massachusetts-based metalcore band Converge, and for his creation of the iconic female image on the cover of their 2001 album, Jane Doe. He is the co-founder and co–operator of the record label Deathwish Inc., which has released some of the most crucial hardcore albums of the last two decades. He has created album and merchandising designs for dozens of bands, and his fine art has appeared in galleries around the world. He also sings and plays in the band Wear Your Wounds.

Conversation

On multitasking, craftsmanship, and letting go of your work

Musician and visual artist Jacob Bannon on balancing the demands of running a record label with a creative practice, and what it means to put things out into the world and let them have their own life.

As told to J. Bennett, 2982 words.

Tags: Music, Multi-tasking, Business, Inspiration, Process, Focus.

You seem to be constantly multitasking—moving between bands and your label, your fine art stuff, and your design work. From an outsider’s perspective, it seems like that could get chaotic. How do you manage it?

There’s some times when it can feel a little daunting, but it’s all about organization and timing. There are some times where, all of a sudden, you’ll look at what you’ve done and you think that you have a free and clear schedule for a little while. And you then look at your to-do list and you realize that you have six little things that aren’t really so little that you have to deal with.

Today is a good example, so I’ll walk you through my day: Wake up in the morning, hang out with the family, make them breakfast and coffee and stuff. Head out for the day, come to the Deathwish office, try to get through my emails for a few hours, because that alters your day, obviously. Then I have two Deathwish records for upcoming releases that I had to format for CD and cassette that I’ve already done the vinyl designs for and had those approved. So that takes some time.

Then I had orders to pack from my own store, which I do myself. And I also had some other Deathwish work to do on top of that. I do printing for Deathwish as well, sort of as an outside vendor. Then I’ve had music-related things to work on.

I will never accomplish all of the things that are on the list in a single day, but I try my best at being productive with my time. I like to get out of here at a reasonable hour. I can easily get lost in work if I allow myself to do so, you know? But I’ve realized that after about 12 hours or so, I become pretty useless. There’s a point of diminishing returns.

So you’re basically going nonstop until you decide to call it a day?

I typically don’t take breaks or anything. Once I’m here, there’s always something to do. There’s always a project to tackle. There’s always something to discuss. There’s always some sort of forward movement. So I just kind of stay focused on that and my time here. When I’m not here, I need to be present elsewhere in my life because I really value that time as well. I don’t want to be that person who’s tied to a phone or a device or a laptop when I just want to check out and not do that. And I think it’s important to have that time, even if it’s just a hobby, a family—anything. It’s just super important to have that break.

It’s an interesting juxtaposition, because a lot of people, when they go to work, they go somewhere that they don’t like and they do something that is a skillset that they just happen to have or whatever. It’s a career path. But I’m in a rare place where my work is something that I love and cherish and appreciate. So yes, the things that I do outside of here are different, you know?

You get to make art at work.

Right—whereas some people will make art and music on their downtime or work within the confines of being creative only as a hobby, as a release. And I tend to do physical things when I’m not doing the music and design stuff. So my work time is creative time. And that’s not to say I can hang out at Deathwish and play guitar all day or something like that. That would be super fun, and I would be really excited to be able to do that, but there’s also a whole lot of what I’ll define as busy work that has to be done when you run a business or multiple businesses. There’s a lot of customer service stuff. There’s a lot of boring stuff to do. So I do a lot of that as well, just like anybody who has a regular job.

When you have so many different creative ventures going, how do you prevent stuff like that from becoming a chore?

It doesn’t really become a chore because it’s a passion. So I don’t write or make music or make art when I’m not motivated to do so. Design is different. Design is a little bit of a skillset. So I have a skillset that’s been sharpened over 20-something years of creating artwork for bands, or doing design work for record labels and whatnot, that I can apply to a lot of the stuff within my daily life without having to exercise the sort of personal creative part of my brain. The same thing goes for basic copywriting and editing and stuff like that. I can do those things and I can sort of utilize part of the creative me, but not the full creative me, if that makes sense.

Totally. You can turn it up to five or six without going to ten.

Yeah. I guess it’s kind of hard to describe. A lot of the stuff I do is invisible. People know you for iconic images or stuff that’s sort of blasted all over the place, but there’s so much stuff that I do that people just aren’t aware of and they don’t need to be aware of—in terms of design work, in terms of copy, in terms of whatever. I can go to a show or some sort of live event in some capacity for heavy music and I can see at least a handful of merch designs I’ve had some hand in, or logos that have passed through my hands in some capacity. Or even things I didn’t design, but where I’ve had phone calls or emails or correspondence with friends that are designers and I can see, “Oh, there’s my suggestion right there in that thing. I’m glad they did that.” And that aspect of things is sometimes just as rewarding as making something that’s wholly you.

Do you have an overall artistic philosophy? And is that philosophy different for visual art than it is for writing lyrics for Converge or writing music for Wear Your Wounds—or is there an approach that covers all of it?

I think there’s a few things. There’s always a level of craft and intention with anything that’s creative, so I think that’s always present, regardless of what the voicing is. I want to intentionally convey something. The way I feel I succeed in creating anything—whether it’s design work or personal artwork or even music—is: Does it have all the qualities that I intended to capture within it?

And when it comes to personal work, that’s actually a huge challenge because personal work is almost… it’s always fleeting, right? You’re never fully capturing everything that you want it to be. That’s part of the creative exercise. That’s why you always do it, because you’re always trying to refine something and get better and better at communicating through visual art. And I think that I can apply that to almost everything that I work on in some capacity.

Sometimes my intent is for it to be chaotic and crazy, you know? So it takes a little bit to break out of a grid system and do stuff like that. There’s a lot of design tricks and design principles that I’ve always applied to fine art that I actually find to be hindering at times, so I actually try to break away from those things. And it actually hurts my brain to do so. But I try.

The way that I look at it, virtually everything that you’re doing everyday is practice and is craft. So if I’m writing copy or writing bios for a band or creating visual artwork or designing something for an outside artist or something like that, I’m just trying to do a better version of where I left off. And I look at it as an evolution.

You went to design school, right? What did you get out of that experience?

A long time ago when I was in school, one of my design professors said that everything has been designed by somebody, whether it be a construction site and you’re seeing a bunch of Tyvek and 3M wrapping around a building—I’m only saying that because I’m looking out the window right now—but all of that typography has been placed in those places for some reason. Somebody’s made a decision for every single angle in all of those things. There’s been engineering and environmental design in all of those decisions made there.

When the façade is put on that building, that’s going to be a design decision. When the signage is placed somewhere, that’s going to be a design decision. When there’s an advertisement for something next to it on a billboard, that’s a design decision. You can find the things that call to you, that you feel are successful—and you can find things that you feel aren’t successful—everywhere. But the point is, you can always be looking at things with that constructive critical eye—almost like the whole world is up for a critique to a degree—and you can apply that to virtually everything you do.

A couple days ago when I was taking the dashboard of a Sprinter apart and putting a new one in, did that make me a better designer today? Probably. Because I had to sit there and take apart something that someone else designed and learn how they put it together. That’s kind of the way I look at things. Virtually anything I do, I try to apply logic and it kind of builds on this basic idea that everything is about self-improvement and everything can sharpen everything else.

On that note, I have to assume that a lot of your visual art—at least the stuff that’s tied to an album—is in some way reflective of or inspired by the music or the lyrics.

Yeah. Especially if it’s my album or something I’m a part of, then yes. I’m trying to paint a cohesive picture, right? So I’m trying to tell the visual story of the audio aspect of things. And that also continues through client work, as well. For example, I was working on two records for Deathwish that I didn’t do the artwork for, but I did all the design work. I’m trying to convey what I hear in their music through that design. But sometimes that’s not as easy as it seems. You know, sometimes the juxtaposition of evil imagery and pretty music is a great thing. Sometimes it’s not. Sometimes when something is super abstract, it’s wonderful—and sometimes when something is super abstract it sort of leaves you with a question mark over your head. So you need to get the lay of the land with a lot of these projects that have multiple layers of communication and try to tie them together and create something interesting.

Has it ever worked the other way around? Have you ever created a piece of visual art that started out completely unrelated to anything musical, and then at some point it infiltrated your consciousness and became the inspiration for a song or a lyric?

Not really, only because of… well, there are a few things. But really, what dictates everything in this world is economics, right?

It certainly seems that way.

So I’m not afforded the, I would call it a luxury—some would call it an opportunity—to think that way. I can’t necessarily just make art for art’s sake too much, you know? As somebody who has released a bunch of music and writes songs for a couple bands, I don’t write them necessarily with the intention of releasing them on an album or something like that. But economics dictate that’s wasted time, right? So I’m not going to just sit and work on something and make sure it’s never heard or seen.

Everything I do in some capacity has some sort of commercial outlet in the end. And I don’t necessarily always want to work that way, but I’m also not a rich guy. I just don’t have the time. I run this business with multiple people, which is Deathwish. I do design work. I do my own print work, so that’s another job. I consider that a second job. Then I have the music portion of my life, which is also a third job that sort of bleeds into all of this as well. So it’s a lot. And so I don’t have that free time to basically make a bunch of stuff and then put it away and say, “Oh hey, I can apply this to project A, B, or C in the future,” without that initial intent.

I’m almost envious of the people I see who are sitting with an easel at a farm painting a landscape or something. It’s fucking awesome. It’s so great that they can do that. I would love to do that. It’s just time, you know? At some point in my life I’ll get to do that a little more. I have all these ideas for big, large-format things, but the way I’m wired now is always wanting to figure out a way of presenting that stuff to an audience.

You mentioned writing. I didn’t realize that you wrote band bios and things like that. I thought it was strictly lyrics.

Yeah, and actually I think the only sort of creative thing I do that can be a little loose at times is writing. If I’m writing prose or poetry—however somebody wants to define it—that stuff that ends up becoming lyrical content at some point, even if it doesn’t necessarily have a song that it’s going to land in as I’m working on it. So that aspect of creating is more of a refining process after the fact. Writing for me is more of a purge than visual stuff is.

You anticipated my next question. So you’re not one of these folks who only writes lyrics when there’s a song to write to…

No, I write when I feel motivated to write. Maybe I can’t sleep and I have some things kicking around in my head and I write. If I’m in the middle of working on something totally unrelated and I’m inspired to write, I take a few minutes and jot some stuff down. But there is a whole lot of work that goes in after the fact, in terms of refinement, editing, and stuff like that. I have pages and pages and pages of stuff that I write that are basically just ideas and little purgings of content and emotion here and there. That art form is so immediate, whereas visuals take a whole lot of refinement—or at least in my approach to them. Even if they’re a hot mess, there’s a whole lot of refinement in it intentionally. So writing’s just a different thing for me.

Most of your lyrics are deeply personal. When you’re 20 shows deep on a tour and you’re repeating this stuff onstage, is it like ripping a scab off every night? Or are the words dulled because of the repetition?

That’s an interesting topic because it can do a little bit of both. It can heighten it and it can dull it. It really depends on the day and the connection to the audience. I don’t think that there’s a clear answer to that. But there’s another thing, too. When it comes to Converge music especially, after we make it and we release music into the world, those songs connect with people in ways that are either intended or not intended—but either way, you can’t control that narrative. You can only control the narrative of what you put into something. When you add the layer of performing live to that, it changes everything dramatically because then you’re dealing with people’s personal relationships with something that’s also incredibly personal to you.

That song that you’re playing in a room of 500 or a thousand people is going to have a whole lot of different meanings to a whole lot of different people because music is so subjective. So it kind of goes all over the place. I try not to think about that too much, because again, there isn’t much control. You set it free. It’s just sort of out there. And when you’re performing a song and you’re playing a song, that’s your personal relationship with that song.

Say you write a song that’s about sad stuff. Sometimes it is very emotional when you’re performing it. Sometimes it’s not. Sometimes you might be playing an amazingly personal, super emotional song and then all of a sudden, somebody stage-dives and their pants fall down. [Laughs] You know what I mean? There’s so many factors that you can’t control. I’ve definitely been in that moment where I’m playing something that’s deeply personal and then you get ripped out of it because of some other attribute of the environment you’re in. And that’s not a bad thing. It’s just the way it is. So you kind of have to have a little bit of lightness as you play. We’re putting a bunch of darkness into our songs or maybe working some stuff out in our songs, but there’s also a nice sort of levity to things.

Essential Jacob Bannon:

1) Converge - Jane Doe

2) Wear Your Wounds - self-titled

3) Converge - You Fail Me

4) Converge - No Heroes

5) Supermachiner - Rise Of The Great Machine

- Name

- Jacob Bannon

- Vocation

- Musician, Visual artist

Some Things

Pagination