On sticking to your artistic intentions

Prelude

Nicole Miglis has a mesmerizing ability to synthesize experimental production, pop melodies, and classical form into a musical language completely her own, an aesthetic that took root when she was splitting time between DIY music scene and studying classical piano performance at the University of Florida. This bridging of sonic worlds was crystallized during her tenure as a primary songwriter and front person for Hundred Waters, but for Myopia, Miglis was determined to write, produce and perform all of the songs herself. Myopia is the culmination of a lifetime of artistic endeavors, threading moments throughout her entire career. It blends textures and genres alongside instruments and influences—from pianos and strings to harp acoustics and ethereal loops—bridging the gap between classical and modern with an album certain to intrigue fans of electronic, orchestral, and pop music alike.

Conversation

On sticking to your artistic intentions

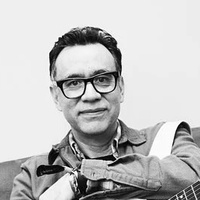

Musician Nicole Miglis (Hundred Waters) discusses working independently, making the simplest art possible, and learning about your process by teaching others.

As told to Max Freedman, 2062 words.

Tags: Music, First attempts, Independence, Process, Collaboration.

Just over three years ago, the official Hundred Waters Instagram account posted that each person in the band was working on their own music but that the band was still working on music together. How did you all know it was time to work on your own music?

I mean, I just knew. I knew that I needed to go off on my own. With the band, we were living and touring, and everything, together as a unit for so long, and after a decade of that, my soul needed a bit of a new direction. Any collaborative relationship can be tough, and I needed to explore creating in my own world again.

While you were realizing it was time to fly solo, how did you realize you should also keep the band together?

We were so close as people. We were still involved in each other’s processes and lives. It didn’t feel like we were completely cutting off from each other and not sharing things with each other. I mean, Tray [Tryon, of Hundred Waters] and I have a very back-and-forth relationship with music. We share things a lot with each other. It’s the center of the band, the center of our process.

We have a good balance of strengths with each other. The band, and the music and community we’ve built, isn’t something I want to get rid of. I wanted to explore my own expression on a very individual level, but that band is such a big part of our lives and we built a lot of things together. We built a whole community, so we didn’t want to erase that completely.

When you talk about this community, it sounds like it’s within and outside the band, so despite you working on your solo debut, Myopia, entirely yourself, did that community outside the band come into play at all in terms of making your first fully solo album?

No, I don’t think it did. A lot of this came from a very personal place. [If anything, it was] more the opposite. It was shying away from that and really going inward, going on my own path, stepping outside the stream the band was going in.

What did you learn about your creative process, and about yourself, by going fully DIY rather than working in a band setting?

I’ve always written from a very solitary place. I usually write songs by myself, lyrics by myself. The collaborative part, bands operate in all kinds of ways, but [Hundred Waters] isn’t a traditional band where we get together, jam out ideas, and come to a consensus. Myopia is more of an extension of my [existing] process. It was just that I didn’t have any other sounding boards. I would see the idea out fully before anybody else’s input. The process wasn’t crazy different for me, although I had to find a lot of answers myself.

What did I learn about myself? I definitely learned what other people were bringing to the table. I have a lot more appreciation for the general team that it takes to put a record out, because I did all this by myself without a label, without a manager, without bandmates. Finding my own timeline was the most challenging part that I learned—instinctually feeling when things had to be done by and the processes that got them done.

When you said you had to find the answers yourself, I felt myself wondering: How did you go about finding those answers, and what were some answers you found?

Time. I think giving things time. For me, songs just have a life of their own. You can force things as much as you want, but lyrics will come out at the most random times, sometimes years later. For me, that timeline could go on forever. Finding those answers, sometimes, they take a lot of time. It takes a lot of trust that you will find the answers.

With anything you’re creating, if you have an intention that it will get done and that you will find that missing piece, you just have to keep the intention. Keeping the intention that you will find the answer is the only thing you can do.

Some of what you just said makes me think about, when I’ve spoken to other musicians, there’s this concept of, “When is the song done? Am I just adding parts to the song for the sake of adding parts to the song?” What’s your relationship to that question when you’re writing music all by yourself?

Half of the time, finishing the album was actually taking things out. I kept adding all these pieces and all these different parts, and then I had to work in the opposite direction of, now, I have so many pieces, and so many parts of this patchwork, that I have to minimize things and find the only thing that needs to be there, and nothing more.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about having a lot and then having to remove it, because my main craft is writing, and that’s my main challenge with writing too. I typically write a very first long draft, and then I have to go back and remove it, but for me, it’s just part of the process. Can you talk about some of the emotions that come with, “Oh, I have to lose this part”?

There’s an emotional part of that, and there’s a technical part of arranging where you just have too many frequencies in one area and you literally have to eliminate purely based on frequencies. If you have parts that are a vocal part versus a bass part versus guitar, a lot of arranging is realizing what frequencies those things are taking up. And a good arrangement should only have that one thing in that frequency. It should all be very balanced and even.

So there’s a technical part, but also, some things can work really well together, and it’s a bit maddening [to eliminate]. From an emotional point with writing, I find the same thing. If I’m really writing from the heart, it’s simple and minimal, and it’s not verbose and flowery, and it really comes from your soul and not your brain. … [Editing means] realizing how much you’re adding just based on the thinking mind, because when you really feel something, it seems to be simpler.

Did you have any specific musical goals when you set out to write Myopia? I hear its singles as somewhat of a different direction for you, but I can see how the music flows directly downriver from Hundred Waters. Was that an intention or just how things wound up while you were creating?

This record is a lot more aligned with where I was going with songwriting. I’m more drawn to really simple songs and timeless songs with very simple lyrics, which are often a lot harder to write, and what needs to be there is just there. With writing, it’s the goal of: poetry wants to distill things.

With Hundred Waters, I was coming from—I was in school for classical piano, and I was [encountering] a lot of very heady, showy, athletic [art]. This world of art that I was writing from—at first, I was really interested in really verbose, florid English writing and poets, and then, I was studying classical music and it was really dense, probably a lot more cerebral, and through more and more writing, I became more interested in simple, less-is-more, and speaking from the heart than more than from the mind.

Now, I listen to just drone music. I’m happy listening to one note as if I don’t need a million notes. I mean, everything in its time and place, but [my solo music has] come from a bit of a different place.

I like hearing you talk about your shift from more of a formal, complex approach to just simplicity, because I’ve experienced the same in my own relationship with what I want from music and writing. For me, when I went along that journey, I had the question of, “Is it valid if it’s simple?” And I know that it is, and you know that it is, but if that question came to you as you went through this shift, how did you address it?

It’s definitely valid. I keep going back to the thinking that it’s heart and mind. If something comes from that place, it’s eternal, and it feels true to me, that’s spirit. You can’t say if that’s valid or if that’s better than something that takes a lot of mind-power and sweat and tears. Also, these songs just came out very quickly, very easily, because I was very heartbroken at the time. It was a very raw, pure state that I was in, and a lot of it just slipped out. It felt very pure and open, and there wasn’t any thinking. It was all feeling. The creative balance is between feeling and the more technical, cerebral part of it.

Do you agree with what a lot of musicians have told me that, even though the songwriting process exists, a musician is less creating a song than catching a song that already exists and then putting it out into the world?

Yeah, totally, yes. I see it the same way as channeling, or you’re in the right place at the right time, with the right feeling, and something moves through you. But the process of finishing something, the mind has to kick in, and it takes a lot of discipline and focus and a totally different [mental] place than the original when it comes out. Sometimes, you’ll channel it and it’ll just be one word you’ll have, and then, you [have] to spend who knows how long until that word comes, and you have to find your own process to allow that to come.

Given the difficulty of making a living in music, have you had to have day jobs at any point over the past decade? How have any of these day jobs, or not having day jobs, shaped your relationship to creativity?

I have somehow, miraculously, mainly just written music. I live very frugally. But during COVID, I wrote ambient music for a meditation app for a little bit. And then I taught piano lessons, which I was doing before Hundred Waters started. I’m teaching and then occasionally writing for other people, but then somehow, quickly, I go back into solely writing. I do exist in my own world pretty hard.

And how has it changed my creative process? With teaching anything, you learn the building blocks of what got you to where you are, which is really beneficial. It makes you more in touch with yourself as an artist and the things that other people taught you, and that you learned from other people, that got you to where you are. It made me appreciate that more and deconstruct this thing I took for granted. Having to teach somebody else the language I was taught, it makes you reflect a bit more on the things you know, why you know them, and how you can tell somebody what somebody once taught you.

I like what you said about teaching somebody this language that you know. It almost sounds like, when you’re teaching, you’re relearning a language.

Yeah, it is like a language. It’s very much syllables and letters and building blocks.

In that way, if you have all these building blocks, you can really shuffle around and reshape your creative process however you want to.

Yeah, and also, with piano, teaching it to somebody else made me explore other things that I probably wouldn’t, because I’m so stuck in my ways with chord progressions or scales, and having to teach somebody, you remember all the things, all the vocabulary you’re not using. I certainly discovered things that I wouldn’t have.

Five essential Nicole Miglis songs:

“Murmurs” (Hundred Waters, The Moon Rang Like a Bell, 2014)

”[Animal]” (Hundred Waters, The Moon Rang Like a Bell, 2014)

“Blanket Me” (Hundred Waters, Communicating, 2017)

“Lure” (Nicole Miglis, Myopia, 2024)

“Autograph” (Nicole Miglis, Myopia, 2024)

- Name

- Nicole Miglis

- Vocation

- musician

Some Things

Pagination