On slowing down and nurturing your friendships

Prelude

Nicholas O’Brien is a net-based artist, curator, and writer researching games, digital art, and network culture. His work has been exhibited in Mexico City, Berlin, London, Dublin, Italy, Prague, as well as throughout the US. As a past recipient of a Turbulence.org Commission funded by the NEA, his work has also appeared or been featured in ARTINFO, The Brooklyn Rail, DIS magazine, Frieze d/e, The Atlantic, and The New York Times. He currently lives in Brooklyn and is Assistant Professor in 3D Design and Game Development at Stevens Institute of Technology.

Conversation

On slowing down and nurturing your friendships

An interview with artist, curator, and writer Nicholas O’Brien

Your work bridges many creative disciplines, from writing, to researching, to designing games, to making digital art. What’s drawn you to mixing all these different mediums?

This is a good first question, because it speaks to how I approach my creative practice in general. I like to really think about how different mediums and formats can communicate different ideas. For instance, a game (as a medium) has different ways in which it gets people interested in its content, and an essay obviously has different ways, too.

In terms of what draws me to mixing mediums, I’m inspired by people who do a lot of different types of things. I get nervous about being pigeonholed as one specific type of person. I like being curious, and I like my work to inspire curiosity. So for me, being able to float between a lot of different kinds of communities, or a lot of different types of disciplines, keeps that curiosity fresh.

What makes you nervous about being pigeonholed to one medium?

I don’t want to get stale. I think I also get nervous about being known for one kind of thing. I like to think of my work as exploring a lot of different types of ideas, even if they’re grouped by specific categories, or by specific formats. I guess my fear of being pigeonholed comes out of not wanting to lose that sense of flexibility, and of creative freedom.

You said you were afraid of being known for one kind of thing. Can you talk more about this fear of being perceived a certain way? Why does someone’s perception of your work matter?

I really like collaboration, and I like learning from experts in fields that are not my own. My worry is that being known for one thing might prevent me from being able to reach out to different communities, or from being able to have opportunities to work with professionals in different fields.

A lot my projects grow out of conversations I have with individuals that aren’t within my discipline, or out of encountering something that’s outside of my work’s immediate context. So the fear of being pigeonholed is certainly one of perception, but it’s also about giving myself permission to encounter a lot of different experiences.

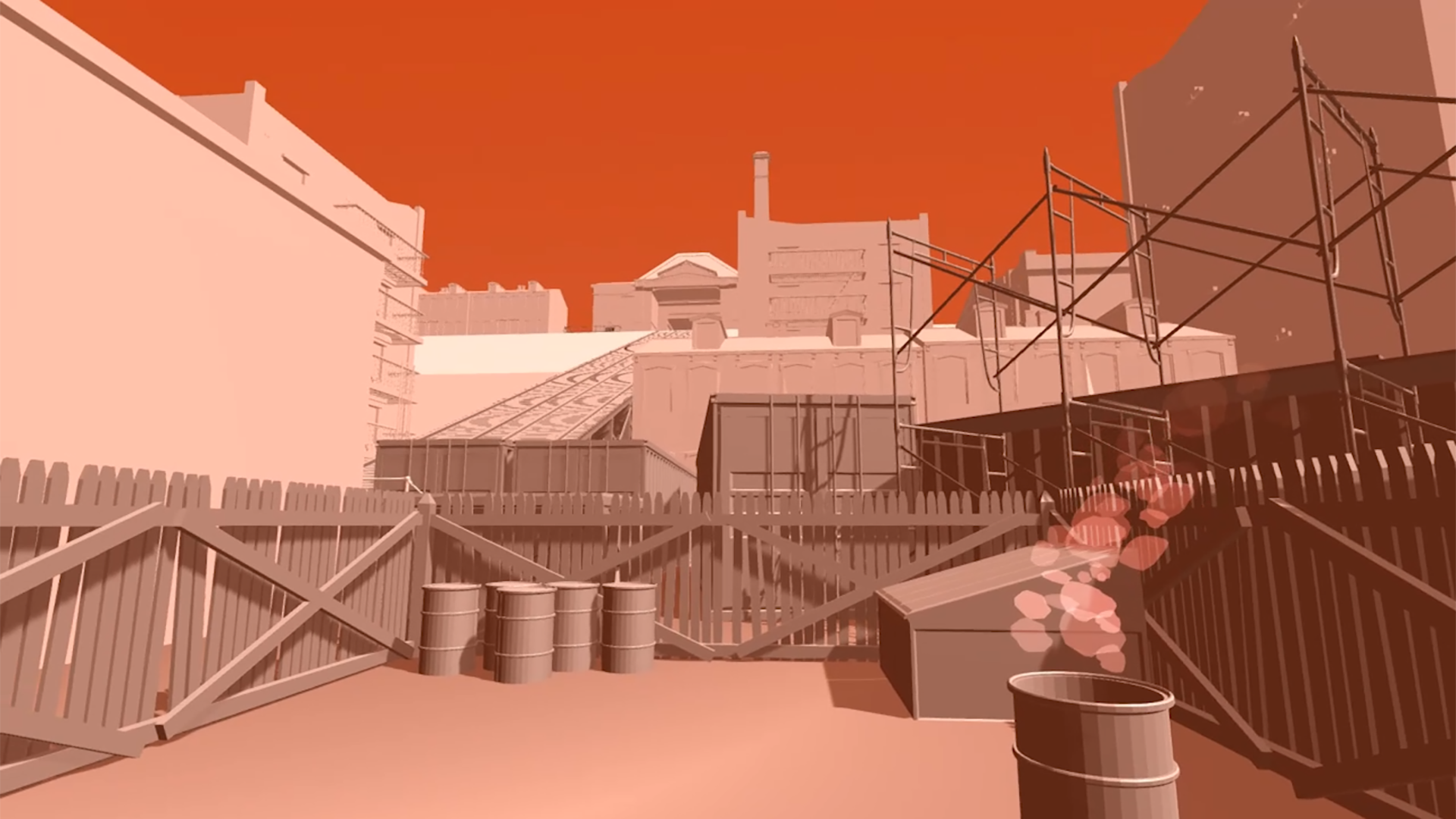

High Frequency Trading (still), Digital Rendering, 2018

It’s interesting—when I talked to Caroline Sinders, she had a different perspective. Because she has a very specific focus (anti-harassment research), she’s become really well known for it, which has helped her get more opportunities. Do you think having a more broad, non-specific focus has made it more challenging to get your work on people’s radar?

In short, yes. But I think while I was developing my artistic practice, I was instilled with the idea of being skeptical of mastery. I internalized this sensibility to allow myself to be broader, or to allow myself to think about lots of different types of disciplines and fields of research.

But that being said, when I reflect on the types of work that I’ve done, I do see a pattern in the areas of interest that, at surface level, might seem quite disparate. And I do think that I’m starting to become known for the type of work that I do, and it’s starting to feel a bit more cohesive. Maybe I feel more scatterbrained than I actually appear to other people. The negotiation of how I’m feeling internally about my own trajectory as a maker, versus how that’s being perceived is interesting, because there’s definitely a disconnect there.

What does your actual research process look like? And what is it about doing research that gets you inspired to make new work?

Most of my research starts with general curiosity. I tend to stumble into projects, either through prompts based on ideas, or themes, or initiatives that other people are putting forward—or just through my own wanderings.

For instance, The Trolley is a video game that I just published. That research started by seeing a plaque in Cincinnati that commemorated the city’s non-existent street car system. As far as I could tell, there was no physical evidence of there ever being a streetcar system in Cincinnati. So after seeing that, my reaction was, “Whoa, that’s really interesting. I should look into this.” I went home and did some research, and discovered that it used to be the second-largest system in America.

Then I just naturally started asking questions like, “What happened? Why is there no more visible evidence of this?” I’m always wondering if maybe I could explore something from a more critical standpoint, to see if maybe we missed something—like, maybe this plaque is suggesting something to the city. Maybe we’re commemorating the loss of something, or maybe we’re mourning something.

When you’re working on something like The Trolley, what percent of your time is spent on research, versus game development, and other types of production work? I’m curious about the ratio there.

It differs from project to project. For The Trolley, the research component took almost a year and a half, and then the production happened sporadically, maybe over another year and a half. There was a lot of pre-production and research work, because it was really important to me to be visually faithful to the original architecture, machinery, and scenery. The initial foray into that project entailed a lot of image collection, and a lot of researching of different narratives that stemmed from that history. Then, it was all about trying to think of appropriate ways to apply that research.

Because it takes such a long time to move through the different phases in a project like The Trolley, do you ever just get sick of what you’re working on?

Yeah, all the time. There was a moment recently where I was working on a project that I wasn’t able to find a home for, despite having been poking away at it for several years. I realized that I had just lost sight of what the purpose of the project was. When that happens, I try to remember that things might re-emerge, or sometimes ideas will come up again, and the conversation will come back around. Also, when I get stuck, I try to get other people to look at what I’m making, and to give me some feedback. It helps to understand what the things I’m working on might mean to other people.

Do you get sick of working on computers? Do you feel the need to move off of computers, and into other types of creative work sometimes?

More recently, I think a lot of my work has been based in conversation. So when I’m starting to feel fatigued from screen time—especially when I’m working on 3D animation, or when I’m working on something that’s rendering-intensive—I call someone and continue the research side of what I’m looking at. Or, maybe I’ll have someone over for a studio visit to just look at the stuff I’m thinking about or mulling over. Or, I meet up with a good friend. I guess the way that I battle fatigue is by returning to the conversations that I’m hoping that the work is having, and then trying to see if that conversation can re-inspire me. So yeah, I do get fatigued a lot of the time, especially when a lot of my entertainment comes from screens, too.

The Trolley, video game, 2017

When you were talking about calling people or having studio visits, what types of people do you bring in that way? And how do you initiate those kinds of relationships?

I think that the people that I go to frequently are people who I think are critical, but also funny. People that have a really good sense of humor about looking at something that could be complex, or something that has a lot of tension. Another thing that I’ve learned to value as I’ve gotten older are people who ask a lot of questions, and people who are curious about things they don’t understand. A lot of the time in art contexts, people feel like they’re expected to know everything. So I’ve gained an appreciation for people who, when you start talking about something that they don’t have familiarity with, will interrupt you and say, “Hey, can you explain that to me?”, or “Hey, I don’t know who that person is,” or, “What’s this new technology that you’re using?”.

In terms of how I invite new people in, I think a lot of the ways that I do that gets back to this idea of research. I tend to ask my immediate community if they have people in their community that maybe know something about what I’m doing. Then I try to expand my network, based on pre-existing communities, or already existing friendships. So yeah, I grow my network just by asking.

As you’ve carved out a space for yourself in your work, can you remember having any “a-ha” moments?

I think an “a-ha” moment for me was learning that I could work at a different speed than that of my medium. Digital art, new media, online publishing, and anything to do with computers has this very quick and demanding output regimen, and learning to work outside of those demands has been very helpful. Being able to be slower, being able to be more methodical—really just being able to work on projects that take a couple of years.

A key part of this has been learning how to do iterative releasing, as a way of participating in those demands. So, when a whole project isn’t finished or released yet, I can give people indications of my progress on that project as a way of still participating in those cycles. That’s been a real positive for me, to just be like, “You know what? It’s okay to take my time. It’s okay for me to dwell in the space of my work.”

Another thing I’ve learned is how to emotionally and physically understand when I’m ready to be productive, versus when I’m not. I think sometimes, especially working with computers, fatigue is a real thing, and sometimes I beat myself up for not being as productive as I want to be. Really being able to recognize in myself, when I’m able to be more productive, or when I really need to focus on other things like health, or relationships, or my family, or politics, or whatever it might be, is important. I’ve needed to teach myself that those things are just as important as making my work.

It’s really intense to try and keep up with all of the churn. Related to this, how do you manage to make a living while you’re working on all these different things?

I teach. Actually, this notion of curiosity, discovery, sharing, and collaboration really stems from being in the classroom a lot. So that’s the nuts and bolts of how I maintain my finances, but it’s also seeking opportunities where the work can pay for itself. That’s been really important for me. So, collaborating with arts organizations, or with publications, or with outlets of one kind or another that are willing to pay makers, creatives, or writers for their labor.

For those types of opportunities, how do you find them? Or do they find you?

I ask. I try to be as transparent as possible, and I try to feel confidant saying, “Oh, that requires work, and if I’m going to work on doing this, I’d like to be compensated.” It’s important not to be shy, or ashamed, or bashful in asking this, or to think of that question as putting someone else in the hot seat.

I’ve really taken inspiration from other artists who have done that with projects that I myself have tried to organize. For me to very humbly say, “Unfortunately, I actually don’t have a huge budget for this, but I do have something to offer you.” Some artists will say, “Okay, cool, that’s great, I appreciate it,” and for other artists, it’s like, “I just can’t do that for what you’re offering.” I just try to value and respect that exchange as much as possible.

In the Hollow of the Valley, video game, 2015

How do you go about setting a value for the work you’re going to do? How do you decide, “This amount makes it worth it?”

I often don’t know when things are going to be valuable, and when things are not. I think figuring that out is part of the risk of being an artist, right? Some things you’re going to feel will be really valuable, and you’re going to work really hard on them. And then when they happen, they won’t have that immediate pay off that you’re looking for. Or, maybe it backfires on you, and you’re hoping that something that you do instigates a really positive debate, but it actually becomes not so good, or reflects on what you’ve been thinking about in a negative way. It’s always a risk.

But I do think taking that risk is part of the responsibility of being an artist. Trying to put out ideas, and put out perspectives, or voices, or history, or whatever you want to say, and not knowing how (or if) it’s all going to materialize into value. In a lot of ways, when those things end up being valuable, I think of myself as being kind of lucky.

I’ve learned over time to shed those layers of worrying about where a project is going, who’s going to see it, what organization I’m going to partner with, and stuff like that. And instead, be like, “Maybe I just need to first focus on starting to do the work.”

What are some habits you’ve developed over the years, that have helped you push your practice further?

Getting regular exercise has been a big habit of mine, more recently. Again, being in front of a screen and sitting for a lot of time is not super healthy. So I try to be as active as possible, by riding my bike to the studio, riding my bike home, going for a run every now and then. I also take really long walks. New York is such a legible city, at the sidewalk level, that I really enjoy just walking between boroughs from Queens down into Brooklyn. Or, across the Williamsburg Bridge, into the Lower East Side.

Another important habit I’ve developed more recently is reading things for pleasure. Reading novels, reading more critical literature that’s not for something specifically, but just for my own enjoyment. I think I’m the most inspired when I’m reading for enjoyment.

One last habit I’ve formed more recently is not using the computer after certain periods of time for work. So—especially during studio days—being very clear about when work ends. Again, I think that gets back to what we were talking about this idea of constant cycles, but really allowing myself breaks, and saying, “Oh, it’s okay that you’re watching Netflix right now, it’s 8:00. Nobody’s going to answer this email right now anyway.” So just giving myself a little bit of breathing room, and not feeling like I need to be on, all the time.

If there’s one thing you wish somebody had told you five or 10 years ago, what might that be?

This is going to sound weird or self critical, but to be a better friend. I think in the past five to 10 years, I’ve moved a lot, and over that amount of time I’ve lost touch with people that I really miss. Some of those people have gone on to do amazing things in a lot of different fields, in a lot of different capacities. A lot of times in the contemporary art world, cycling through communities, or cycling though professional acquaintances, can get really exhausting. So more recently I’ve tried to nurture a core friend group, and make sure that those people know I value them, and value their input, and feedback, and support. I wish I would have realized this a long time ago. Just like, “Remember to value your friends. Remember to tell people that you value them.”

Treatment: Prologue, HD video, 2016

Five encounters of alternative creative expression in/around video games:

-

Wadu Hek - a Twitch Stream Sniper who tries to play with prominent professional gamer Michael “Shroud” Grzesiek and only says “Wadu Hek”

-

Civ 5 FIFA World Cup Host Resolution - a political satire game mod for Civilization 5 where you can compete to become the World Cup host, but in order to win you need to create massive amounts of migrant workers

-

Manifesto Game Jam - a game jam is a local or distributed event where people make games under specific time and theme constraints. This jam focuses on the creation of Manifestos

-

98 Demake - youtube channel dedicated to de-res’ing games — turning contemporary games into nostalgic/early 3D low res animations

-

Game Workers Unite - a grassroots organization attempting to create game industry unions

- Name

- Nicholas O’Brien

- Vocation

- Visual Artist, Curator, Writer

Some Things

Pagination