On moving marginalized bodies from the periphery to the center

Prelude

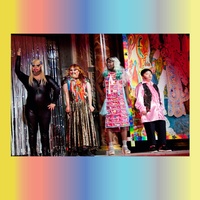

Kamra Hakim is a Brooklyn-based organizing artist and entrepreneur devoted to the power of imagination, exchanges centering marginalized bodies, intimate gathering, and radical discourse as pathways to creative liberation. Their work realizes the futures queer artists need now through accessibility and inclusion.

Conversation

On moving marginalized bodies from the periphery to the center

Organizing artist Kamra Hakim on starting a residency for underserved artists, healing as a way to unlock creativity, learning new ways of being in the world, and community building as a collective venture.

As told to Willa Köerner, 3814 words.

Tags: Art, Culture, Process, Day jobs, Beginnings.

What gave you the idea to start Activation, a weekend-long residency in upstate NY?

The idea for Activation emerged after working at Bonnaroo two years ago, where I was hired to be an “ambassador,” which I would consider a glorified party thrower. We were working with Cage the Elephant and other local artists. I had to find creative ways to engage the audience, and keep the party alive, and also keep people safe, and decorate the space in a way that felt homey to folks. It was my job to figure out small moments where everybody was engaged.

In doing that, I felt like I started to understand the essence of what it means to activate a space. Running with that idea, I wanted to provide people with the opportunity to activate their own creative practices within a larger space. As an experience, Activation operates as a four-day immersive residency for underserved artists in Upstate New York. But as my own art project, it’s an experiment in how social systems operate when marginalized bodies are moved from the periphery to the center of our discussions and realities.

I know that this year was your second year of holding Activation, right? I’m curious, can you give an overview of how you actually got it off the ground?

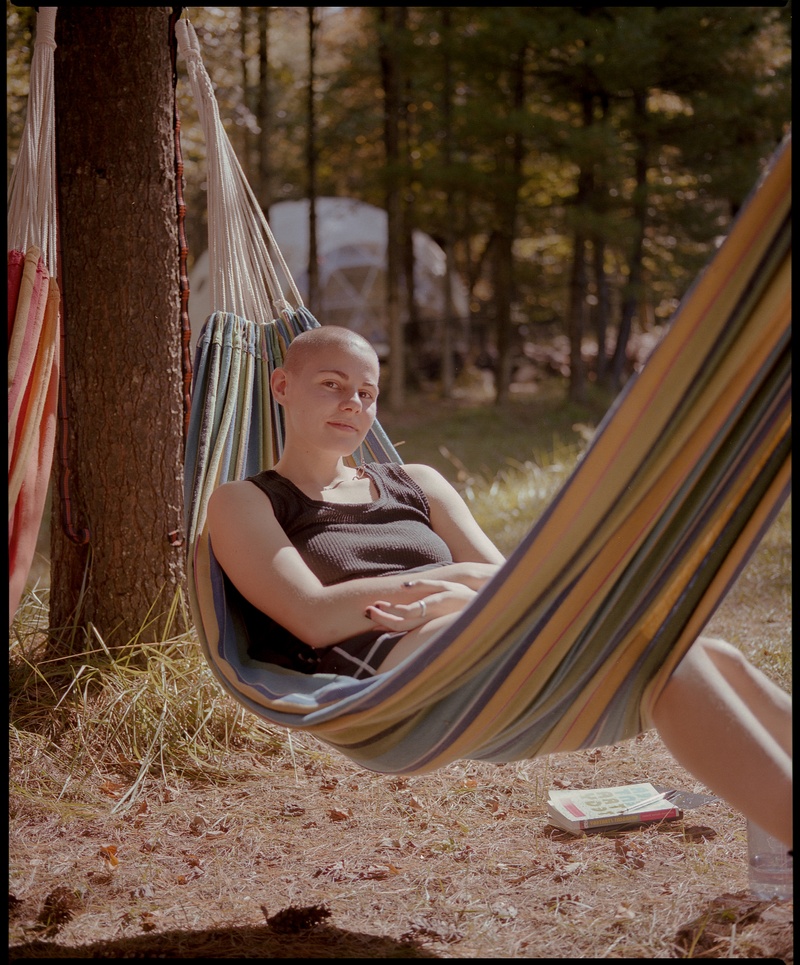

My first step was the ideation, so having this loose idea of an experience built around the broader concept of “activating.” I knew I wanted it to be for underserved artists, because as an underserved person who is surrounded by other underserved artists whose work I am inspired by, it felt really important to me that I was providing something for the community that I’m familiar with and accountable to. The ideation phase was a lot of dreaming and just imagining what this space could actually look like. I knew I wanted it to be in nature, and so I just started moodboarding what I wanted to see in this reality.

My second step was asking for help. I have a few friends who are building an artist space in Hudson, New York. I texted them and I was like, “Okay, this is my idea. I want to do this residency. Can you recommend any spaces?” They were immediately like, “The Outlier Inn.” I think that’s another secret of creating: when you start to ask questions and ask for help, things just pop up really easily. That’s one demystifying thing that I’ve experienced in my creative process.

So once I found the space, I was like, “Okay, I know that I want this experience to be activism and healing-oriented. So for me, what is healing? I decided part of that was about having really good, nutritious, locally sourced food. So I started doing research on how I could provide artists with a variety of food that would meet everybody’s needs, that was also local to the land we’d be spending time on. I found this place called the Center for Bioregional Living. I touched base with their main farmer named Adriana, and we just vibed. I was like, “Okay, this is my lady who’s going to do the food.”

Then, I went into implementation as a third step. “How are we going to fund this? What does that look like? How much are people going to have to pay to participate?” Because we have no backing, and no outside funding. We have to do this super DIY, so that meant we had to figure out equitable pricing, how we could do trades with people, how we could have people lead workshops in exchange for a free spot, things like that.

I think the fourth step, and one of the most important steps—but also a step that I had to be thinking about since the beginning—was the online presence. “How are people learning about this experience? Who are we going to draw in?” Instagram was a huge part in advertising Activation as an experience for people. It’s how something like 85% of our artists found us. We also had to do a website to share all of the information and things like that.

And then the actual participation happened, which would probably be the fifth step.

Photos by Tonje Thilesen

Can you share more about the way that you funded Activation? What was the actual financial framework that you ended up with?

Our first year, 80% of the costs were covered by artist participation fees. I just broke that down based on the total cost, and it was important to me that nobody would pay more than $250 for a spot. The other 20% came from me personally. I put my money towards the project because I really cared about it and I wanted to get it off the ground. Making this model work was all about the people participating in the project believing in it so much that they were like, “Yeah, I can pay $250 for this experience, and to see something like this become real.”

In terms of getting people to believe in the project, can you talk about how you sent the right message to get people on board?

For me, it was about getting clear on the language. “What are we actually offering, and who are we offering it to, and why?” I just wrote down a lot of questions, and I’ve seen myself iterate the language as time goes on. First, Activation was for “black queer artists and their comrades,” and then it switched more to “underserved artists” because the number of artists who are underserved is so overwhelmingly vast, that to go too narrow meant we couldn’t speak to what we’re actually trying to do with mixed gathering.

One of my really, really close friends, Tonje [Thilesen], she’s a photographer, and she did a really good job at seeing my vision and understanding what angle we were trying to create. Some of our values, like intimate gathering—a lot of that was captured in the imaging she created.

Beyond that, me just having such close personal ties to the project, and being able to come up with language that I not only use in my day-to-day, but also language that I want to use to sculpt the realities of what I want to see. That kind of language became more prevalent as I started engaging with artists from a spectrum of backgrounds, needs, abilities, and disabilities—and it clarified through lots of experimenting and lots of iterating.

What were some of the biggest things that you learned from the first year, things that gave you momentum to iterate for the next year?

One of the most poignant examples is just scheduling, because when you’re planning a schedule before something’s going to happen, you have it in your head that, “Okay, this is the programming. Things are going to go as planned.” But that first year, I didn’t calculate for lapses in time. So by the second day after four workshops, three performances, and lots of meals and hanging out, people were exhausted.

People woke up late and missed half of the day of programming, and in order to get back on schedule, we had to have a town hall to figure out how we wanted to move forward. Did we want to figure out a way to incorporate the workshops? Did we just want to skip straight to the performances? Based on that experience, this year, I was really, really good about setting expectations beforehand and letting facilitators know that we have very hard start and stop times. I also scheduled fewer activities so people could have more time for leisure.

I would say those were the two adjustments, and this year, everything flowed perfectly. We even had pop-up moments of new activities happening that weren’t on the schedule. So that was awesome.

Photos by Tonje Thilesen

Can you talk a little bit about how you define “artist” in the context of this residency?

On the website, we say even if you’ve been dancing for two weeks or painting for five years, you’re an artist. I say that because I’ve seen creative tendencies in every single person I’ve ever met. So for me, I consider an artist as somebody who is interested in using their body and their mind, and maybe they’re showing up in their community as art. I call myself an “organizing artist” because my art is a concept, it’s a movement, it’s an installation of sorts, and so I feel like I have a pretty wide scope of what an artist can be.

How do people react to that? Do they feel a little bit relieved, or do they struggle to enter into that definition of themselves?

I think in this year’s iteration of Activation, I experienced people leaning into that. I saw so many people painting. I saw people playing guitar to each other, dancing, vogueing in the courtyard. I think that people really leaned into those identities. I will say there were a few folks just in my periphery who were like, “Yeah, I don’t feel comfortable applying because I don’t feel like an artist.” I had one person sign up but then back out because they hadn’t been practicing recently, you know? So I think certain people have parameters around what it is to be an artist and how to be an artist, but I think leaving the window open for the sake of accessibility and the sake of maybe seeing art as a window to other areas—such as activism or healing—is important.

Can you talk a little bit more about the connection between healing, creativity, and the community that you’re serving?

The healing component for me is deeply rooted in zooming out and looking at generations before us. “Were those lineages in ritual? If they were in ritual, how? Were they experiencing lots of pain? What was happening there?” For folks like me who are Black, queer, and nonbinary—who come from demographics and backgrounds that don’t necessarily have access to direct healing—to provide people with even just the modalities was important. We had a massage therapist there this year. We gave away free massage. We had several reiki healers, and we gave a lot of those sessions away.

I think for artists at this residency, just having access to that was really important. An example in my life would be I’m currently training as a singer, and I’ve been studying the somatics of my body a lot as of late. I noticed that when I’m singing and I’m trying to access certain points of my voice, I was experiencing pain in my lower back. In order to address that pain, I went and got some acupuncture done. Now when I sing, that pain is no longer there. So it’s like, “How does healing our bodies actually give us more access to our creative practices?” I’ve been thinking about that a lot in my personal life, as well as within this project.

Going back to what I was saying earlier about this being an experiment on how social systems shift when marginalized bodies are prioritized, the activism involved in this project is based around us establishing a shared ethos, and then watching that come to life. As an example, we do a lot of decolonizing work. “Access” was my word this year. I’m like, “This has to be accessible. It really has to be a radical space.” I think in saying that, I was able to hold all of the community members accountable to making that happen.

So on the second day of Activation this year, a few of the participants recommended that we do an access check-in so that folks could announce who they are, what their pronouns are, and what their needs are. We all gathered in the dome, and one by one, all 60 people said their name, their pronouns, what they can offer as a community member, what they can’t offer, what their boundaries are, and what they’re seeking. It was just the most intense experience of my life, but so valuable because from that point forward, everything flowed. Everybody’s needs got met. Anybody who was celiac got fed. Folks who had trouble sleeping got earplugs and their own mattresses. Folks who needed books bought, they got their books bought by other people.

It was just so beautiful to see the community come together and perform a level of activism that doesn’t always happen so readily. We had this pad that was going around camp where folks can write their needs in case they were too embarrassed to say them out loud. Just seeing that activism happen in real time was so powerful.

Photos by Tonje Thilesen

I’m interested about this idea of being more forthcoming about the resources you have and you can offer, versus the resources you need. How do you think that idea can carry over into daily life?

One thing that I’ve been thinking about a lot is that you can’t change the world in one weekend, but you can use one weekend to change the world. I’ve been finding ways to perpetuate that ethos, like you said, outside of the Activation experience. One way we were able to do that is by starting an ally affinity group. Since Activation happened over a month ago, an ally affinity group has started meeting in Brooklyn. That group talks about everything from how to use your generational wealth if you have it as a white person, to subverting white supremacy, to why we don’t use AAVE, which is African-American Vernacular. Seeing that group come together to discuss ways to continue the allyship was important to see.

We’ve also been adopting the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective pod maps. They’re these maps that help you orient folks in your life who can hold you accountable, and you can hold them accountable. Feeling rooted in community, and being able to identify and locate safety in the people around you is something that we’ve been practicing outside of Activation.

How do you teach or show people how to feel comfortable in radically accessible spaces? Do you have any specific tactics that you use to give people a quick start into feeling comfortable in the space?

For me, the big thing this year with just safety, and vulnerability, and how important the two are. I was really adamant about having an application process that determined folks’ intentions for wanting to enter a space like this. I asked questions like, “What do you do when you experience harm? How do you reduce harm in spaces that you enter? What will we learn from you?”

Another recommendation would be just to get people comfortable answering questions by asking, “What makes you feel comfortable? How is this going to be a healing space for you?” Because I think that process of unearthing vulnerability is different for everybody, and getting folks to tap into what safety looks like for them is the best way to be able to accommodate that.

Additionally, I think codes of conducts and community guidelines are great because when done right, they’re based on consensus. That means that they’re a list of guidelines that the community will abide by to keep everybody safe and make everybody comfortable. We didn’t necessarily do a written code of conduct this year, but we did vocalize some guidelines around how the community would interact with one another.

As an example, nakedness came up this year. So we had everybody close their eyes and asked the group as a collective, “How does everybody feel about nakedness? Should we have a specific zone for that to happen?” Collectively, we all decided that the naked zone would be at the pond. Just not shying away from the things that might be uncomfortable.

Photos by Tonje Thilesen

As the project evolves, how are you balancing your vision with other people’s visions and input?

I think the balance is in understanding my work as maintaining the container which is Activation, and then making space for the fact that things are going to move, shift, iterate, and grow naturally.

For example, this year, things were coming up from the first moment to the last. The second I got done signing everybody in, somebody was having an issue with food. People were coming to me with ideas, but since the container was already made, all I had to do was make space to listen to people. Somebody was like, “Yeah, we should do an access check-in meeting.” I was like, “Okay, wonderful.” Somebody else was like, “We should make sure that there’s a naked zone.” I was like, “Okay, great.”

I was exhausted, but during the access check-in meeting, I made a request that every day, I would get two hours off to not do admin work. Once I said that, it was like nobody came to me for anything. Everybody was helping each other instead of coming to me. It really is about giving people the space to have agency. I talk a lot about active participation because community doesn’t just happen when one person decides to do something. It’s a collective venture.

I think everybody felt collective responsibility over the experience because we established that we were going to care for each other. That was just what it was. There were no ifs, ands, or buts. This person’s celiac? We’re going to make sure they get the right food. There’s no not making it happen. That was just the energy that everybody carried throughout the weekend.

Photo by Tonje Thilesen

I’m curious to know how you as a person are supporting yourself. How do you make a living?

I have two part-time jobs. One of them is at Columbia University. I work as a professional development coordinator for arts administration students. I’m sort of the liaison between the students and the professional world, and just help them help themselves. Then I work part-time at Doris bar in Bed-Stuy, and that’s it. I just barely have enough money to pay my bills, and then everything after that goes towards Activation. I do have a lot of community support. Emotionally, my friends support me, and I do the same for them. We have a lot of dinners together, community dinners. I have food stamps, so that really helps. I’m really in the trenches.

I mean, that’s an important thing to acknowledge because if I hadn’t asked you that, people might assume that you were somehow able to fund your life through something like Activation. It’s important to find out that everyone doing this kind of work is hustling on the side to be able to do what they want to do.

Absolutely. I think there’s creativity in being a low-income artist, because you have to find creative ways to continue your practice. You have to realize that there are other resources, like in-kind donations, and actual connections with people. There are so many different kinds of resources to make things happen. I think that’s another thing I’m realizing too, as I grow this project.

When you’re working two part-time jobs and working on Activation, how do you make sure you’re not totally burnt out and stressed out all the time?

Honestly, I’m just trying to find new ways of being in the world. After growing up in a poor Black family, I had a really intense academic experience where I traveled all over the world, saw a lot of things, and branched off from my family in order to create a life of my own. I think as somebody in their late 20s who’s feeling like they’re dying and being reborn over and over again, I think it’s really important for me to see things in the world that I want for myself, and then find ways to be those things.

For example, I’m learning a lot about what it means to identify maladaptive behaviors in yourself and how to heal that by going to therapy, and finding new ways of coping. I’m learning about compersion, which is the notion behind polyamory, of how do I be happy for somebody I love loving someone else? I feel like I’m creating balance by adapting these new ways of being. A lot of those ways of being come from this project, which is really beautiful for me.

Therapy is also really huge. Staying on top of my mental health, getting lots of rest, letting myself enjoy being alive, letting myself eat ice cream, and laugh a lot, and have wine when I want to. Not taking life too seriously is really important for me, and just trying to remain childlike, honestly. Those are the things that help.

Photo by Tonje Thilesen

If you could go back in time to about five years ago, what one piece of advice would you like to give yourself?

It honestly probably would have been to come out sooner. Be gay sooner. I feel like I have a lot of symptoms of late bloomerness because I didn’t really get the opportunity to express my queerness as an early youth. Now that I feel safe enough to be queer and express that in my relationships, and my gender, and my politics, and the way that I move through the world, I’m like, “Wow. I could have been doing this and being free all these years.” Because I just feel like it’s such a fundamental part of the way that I am as a person.

But for me, the bottom line in my queerness is using my experience in this body to challenge the status quo, and to actually see the values in my heart in the world. And then, to see generations after me live in ways and in places where they can feel peace and joy.

Kamra Hakim Recommends:

- Decolonizing Nonviolent Communication by Meenadchi

- Activation’s video

- How to Not Always Be Working by Marlee Grace

- BATJC’s Pod Maps

- Abolish Time

- Name

- Kamra Hakim

- Vocation

- Organizing artist, Entrepreneur

Some Things

Pagination