On making the most of each moment

Prelude

Chelsea Ryoko Wong (b. 1986, Seattle, WA) is a painter and muralist. She attended Parsons School of Design, New York and received her BFA in printmaking from California College of the Arts. She is the first recipient of the Hamaguchi Emerging Artists Fellowship award at Kala Art Institute, Berkeley and was a 2022 finalist for SFMOMA’s esteemed SECA Art Award. She has participated in recent group exhibitions at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Creativity Explored, Chinese Cultural Center, and Bolinas Museum. She will enjoy her second solo show with Jessica Silverman in July 2024. She has completed large-scale mural projects in San Francisco at Asana; La Cocina; Facebook Artist in Residence Program; and forthcoming at the Asian Art Museum. Her work has been acquired by institutional and private collections including de Young, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Crocker Art Museum, CA, and Bolinas Museum, CA. Wong lives and works in the Mission District of San Francisco. She is represented by Jessica Silverman, San Francisco.

Conversation

On making the most of each moment

Painter and muralist Chelsea Ryoko Wong discusses challenging yourself, changing focus, and being conscientious of how you use your time.

As told to Eva Recinos, 2888 words.

Tags: Art, Education, Money, Failure, Success, Identity.

You received your BFA in printmaking and now your work uses watercolor, gouache, acrylic, and other mediums. I wondered if you could tell me a little bit about how your training in printmaking informs your work today. Was there a moment that inspired you to shift your focus from printmaking to working in a variety of mediums?

I went to California College of the Arts for printmaking, and before that I was at Parsons and I was studying illustration and communication design with a focus on sustainability and entrepreneurship. When I was at Parsons, I took time off and I worked for a printmaker. Printmaking was a way that I could see myself making a living as a working artist. I assisted her and it was cool to see her business model, learn things from her, see how she worked in the studio. I went back to school for printmaking at California College of the Arts—kind of on a whim, to be honest. I was interested in the process, like I said. I had seen this person make a living, and it was very fun to me and very exciting.

So when I was at CCA, I was studying printmaking, but it really became hard for me around my last year. It became hard for me to figure out, “What am I going to do with this? How am I going to become a printmaker?” Around the time of my senior show, I actually stopped making prints and started drawing and painting. There was a time crunch. Printmaking is very process-based, and for that time crunch, I didn’t feel like I could make a solid show of all prints. That’s when I transitioned.

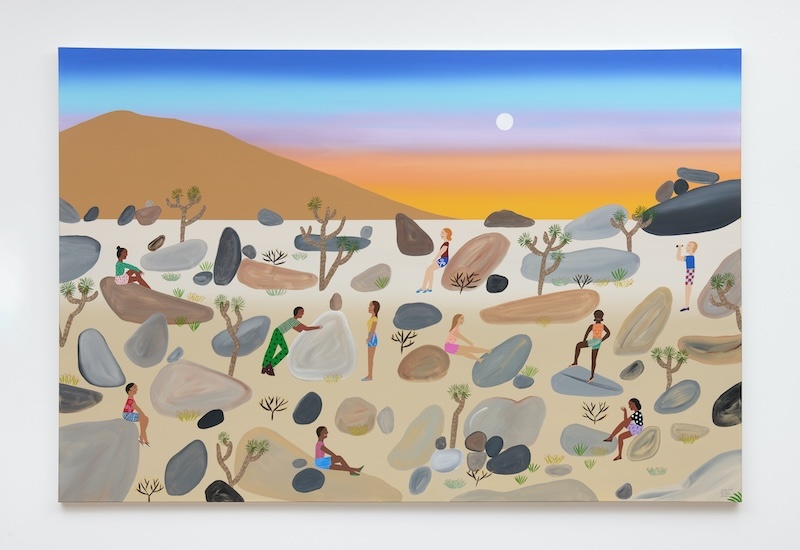

Chelsea Ryoko Wong, Hot Rocks on a Hot Day, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 72 x 1 1/2 inches / 121.9 x 182.9 x 3.8 cm, photo by Shaun Roberts

And also, after graduating, there wasn’t really a lot of access to printmaking studios. I had received an Artist-in-Residence from Kala Art Institute’s printmaking studio in Berkeley, but even that was really hard for me to get out to. I wanted to continue my practice, so I just started drawing and painting. But the way that I draw and paint is very much informed by printmaking. If you take a look at one of the paintings, for example, it’s like I’m working in layers that are very flat. They would work well for something like screen printing but, for me, I like the immediacy of putting paint on a canvas or watercolor on paper versus the multiple, and multi-layered, process of printmaking.

I think a lot of folks might have similar experiences where they start in one genre—or one major if they’re in school—and then they think, “Well, can I switch my focus?” How did you give yourself the space to do that?

It was really just a time crunch. I’m not even sure if I thought about it at the time—if I gave myself permission, in that sense. I definitely just started doing it. I liked the immediacy of it versus setting up a screen or a plate and doing 10 steps to achieve an image that is the size of an 8-by-10 piece of paper, for example, or 11-by-14. I felt like there was just so much more that I could do. I don’t think I made a conscious step, if that makes sense, to go from one medium to another. It just felt natural to me, and I grew up painting and drawing.

One thing that I was really drawn to in your work is your use of intricate details, whether the landscapes that are in the background or the food dishes that are depicted. How do you know when an artwork is done?

That’s a very timely question. I’m working on a painting right now that is about Tunisia. I just went there a few months ago and there was so much to look at visually. There’s tiles, there’s fabrics, there’s noise, there’s everything. It’s a very visually rich country and place. I’m working on this painting and I’m looking at photo references, and it’s like, your eye goes everywhere in these photos from the markets there. When I was making this painting—I am at the place where I feel like it’s done, and yet I want to keep on going. I want to keep on adding to the painting. So at this point, just a few days ago, I sent it to a few people and I’m like, “Do you think this looks like it’s finished? Or do you think I could add this thing or that thing?” And everyone pretty much said, “No, it looks like it’s finished.” It was good to seek other people’s opinions on that because sometimes I could just keep going forever, especially in something that is as layered as a market scene. But I had to get other people to put the brakes on it for me.

Chelsea Ryoko Wong, Gift from the Sea, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 48 inches / 152.4 x 121.9 cm, photo credit: Shaun Roberts

How did you build that circle of people that you now know, “Okay, I’m going to send it to these people and ask them if the work is done?”

Anyone who walks by. [laughs] Anybody who contacts me or sends me a message or someone I talk to regularly or the people at the gallery. I’ll just throw it out there. Because I think that when you’re in your studio, I get so absorbed in my own practice and my own world and staring at this painting in this room for days on end —and adding to it or subtracting from it—that I just need a set of fresh eyes on it.

One thing that I wanted to mention is the clothing in your pieces. When I saw your work, I thought, “Oh, I would absolutely wear some of these outfits in real life.” I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about where you find inspiration for the clothing in your pieces.

Well, first of all, to go backwards in time, I did go to Parsons originally thinking I wanted to do fashion design. And that was something that was always interesting to me as a young adult. I didn’t end up studying fashion design, but my interest in that world has always been close to my heart. For the clothing and the textiles that I paint on people in my paintings, I get inspiration from real life. If I am out and about on a walk, I’ll take photos of flowers or shadows or leaves. I’ll take photos of shapes… For example, the wrought iron that’s in windows or anything that is an interesting play on positive and negative space. Just like anybody else, I’m getting inundated with imagery all day long.

I was also thinking about scale, because you’ve worked on large-scale murals as well. I recently saw your work at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts as part of the Bay Area Now 9 show. One of the things that struck me was how a couple of your pieces were on a wall near a stairwell, so I could get kind of a different view depending on where I was standing on the stairs. Could you talk a little bit about scale and location and how that influences your compositions?

The series that you’re referring to is about Chinatown and layers. There’s three paintings that are hung on top of each other. When I was thinking about that series, I was thinking about how when we go to Chinatown, we really just see what’s on the retail level, on the floor space. So for example, shops or restaurants, tourist-y places, people trying to give you menus to go to their restaurant. And then there’s what we don’t see, but for example, what we hear is Mahjong tiles that are being “washed,” they’re being shuffled. You can hear them and you’re wondering, “Where’s this noise coming from?”

Chelsea Ryoko Wong, Snow Melt, Secret Swim Hole at the Campground, Discovered, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 72 x 60 inches / 182.9 x 152.4 cm, photo credit: Shaun Roberts

And it’s coming from a basement, down a dark set of stairs that you can’t really access behind a gate. Above that is the apartment level where people live, and there’s a whole world in there that we don’t know about. And so for that piece, and that series at YBCA, I wanted to portray Chinatown in layers and get people to consider what they see and what they don’t see—and how multidimensional that space is. In terms of scale, that is an important factor for me. I am, right now, working on some very large-scale paintings that are 6-by-7 feet. They’re bigger than me. I’ve done murals. I’ve pushed myself to work with figures that are in human scale.

But then I also will paint very small miniature watercolor scenes that are 2-by-2 inches. A lot of my watercolor paintings are in the 9-by-11 inch scale. I’m working on very small things as well. The other series at YBCA, which was three nature paintings, when you come in the hallway, those paintings were based on the way that water moves throughout the state of California. So from the mountains to the river and out to the ocean. And with the scale with those paintings, for example, I wanted to consider how we as humans interact with each other in these different places of nature. For the mountain painting, the figures are very small, and that’s because when you are skiing, for example, people are just whizzing by you, and we all look very small on the mountain.

In general, your work captures a sense of joy and gathering, but you’re also acknowledging or referencing really painful moments in history for Asian communities, as well as present-day anti-Asian hate and racist policies. How do you balance trying to capture the joy and also doing research into really heavy topics?

For somebody like me who grew up as an Asian woman, an Asian girl, I didn’t see a lot of people who looked like me. I come from a multiracial family. I call it the mixed race, multiracial, merged family. My sisters are half Black, half Japanese. We’ve all identified with different cultures throughout our lives, and none of us really look alike. So I call us the brown rainbow. Growing up, I didn’t see anyone that looked like our family. Even to this day, when I go out with my family, people can’t figure out how we’re related. They’re like, “Oh, your friend is over there.” And I’m like, “Hey, friend,” even though it’s my sister.

These types of conversations are always present in my mind and have always been present since I was young. What does it mean to be connected? What does it mean to understand how one culture interacts with another or how we intersect? And how do we look for a deeper meaning within that human connection? My antidote for all of these heavy emotions is to find joy and be grateful and live in the moment and try to be present… A lot of these paintings are savoring these good moments and finding happiness within our daily routines and within our connections to each other. And I feel like painting is a practice, just living a happy, fulfilled life is a practice—it’s something that we work on or, that I work on every day. Some of these paintings are almost like… a meditation for me. It’s a reminder that life can be short, and so we just have to enjoy it for what it is.

Chelsea Ryoko Wong, Big Family Gathering, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 72 x 1 3/8 inches / 121.9 x 182.9 x 3.5 cm, photo credit: Phillip Maisel

There’s also a lot of nature in your work. How do you sort of balance the being outside part of your practice and with the hours that you have to spend inside at the studio?

I’m working on life-work balance right now because I’m under deadlines for a solo show, and I’m very excited about it and I have more or less the next year lined up. I’m trying to figure out how to navigate that. One of the great things is that I live in San Francisco, and so the beach is an 18-minute drive from my studio. If I’m feeling like I need to just be more present with myself or just kind of unwind, I’ll just drive to the beach. I’ll look at what time the sun sets, drive to the beach right before sunset, go enjoy a sunset, and then drive back to the studio and work for the rest of the night.

You mentioned, especially with your large-scale work, this idea of challenging yourself even as you are developing as an artist and getting into a groove. What advice do you have for folks who are trying to challenge themselves, or get outside their comfort zone in their practice?

Challenging yourself would mean something different for everybody… For me, right now, the challenge is to be very disciplined, be productive in my time at the studio, push myself into new content and try to figure out how to take these moments that I’ve experienced and put them onto the canvas.

My challenge right now is also to grow. I want to push myself into painting in a certain way, trying new things on the canvas. But I think challenging yourself, like I said—it’s going to mean something different for everybody. If you have a goal in mind like, “I want to paint every day. I want to be a part of a group show. I want to have a fellowship. I want to work with blank gallery or get a grant,” or whatever it is, just have those goals in mind and work towards them. Whatever it is.

The flip side of that is the fear of failure, or of coming up short. How have you dealt with that difficulty over the course of your practice?

When I think of the word failure, for me personally, things that come to mind are going for something or putting a lot of time and energy into something that I didn’t get. Or putting a lot of time and energy into a painting that wasn’t the right direction. Or feeling like, in the end, “I don’t know if my message or feeling was totally conveyed by it.” I always want to be proud of the work that I do and feel like I’m putting in my best work. So a failure for me would mean coming up short on one of those things.

Chelsea Ryoko Wong, Night Dance, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 72 inches / 121.9 x 182.9 cm, photo credit: Phillip Maisel

I’ve just had to learn from these moments and keep on moving forward, but also be really conscientious of what I put my time and energy into. Do I want to spend a ton of time on a proposal that I might not get? Looking at things in a very pragmatic way. Was that the right project for me? Do I think I was a good fit or the right candidate? When I look at things now, when I approach projects or work, I try to consider those things beforehand and that saves me a lot of time.

Right. Less time working on a proposal means more time driving to the beach.

Exactly. Or working on the paintings that I do want to be working on.

And it sounds like it’s also about keeping your momentum and moving forward. You go into the studio and you keep busy.

Yeah. I mean, even if I am feeling tired or feeling uninspired—if I’m going into the studio and painting a background, for example, just painting a wash of color—I still feel like that is the practice. That is me pushing myself to do something that I love, even in times where it doesn’t feel as enjoyable for me.

Chelsea Ryoko Wong Recommends:

Carpe Diem-ing. Who knows what this actually means or how to properly use it. There’s lots of arguments on the internet. Enjoy life while you can! Pluck the flowers! Seize the day!

WQXR Classical Music Livestream, a gem of many hits. This could help you get into a carpe diem mood.

Talk to strangers. Dine solo. Drink water out of a wine glass.

Here is something fun for everyone. Choose your own adventure world of beans. My favorite recipe, my favorite beans.

The Teshima Art Museum. You can read about it and look at pictures of it, but it can only be experienced in person.

- Name

- Chelsea Ryoko Wong

- Vocation

- visual artist

Some Things

Pagination