Peer Review: Nora Khan interviews Marco Kane Braunschweiler

Prelude

Conversation

Peer Review: Nora Khan interviews Marco Kane Braunschweiler

As told to Nora Khan, 2764 words.

Tags: Art, Film, Process, Production, Inspiration, Focus.

Nora Khan: How did you come to make film? How did you learn? Before I knew your film work, I was first familiar with your time in publishing, namely the space Golden Age you co-founded and directed in Chicago.

Marco Kane Braunschweiler: Before I went to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I didn’t have much experience, or familiarity, with art. When I was 16, I started making skate videos. That was my entry, and fundamental to why I make the things that I do now, both on a compositional and structural level. Skate videos, formally, are experimental videos–they convey meaning through pacing, tone and a shared visual language instead of having an explicit story. At SAIC, I formally studied art, and Golden Age was another way to learn. We signed the lease for Golden Age two weeks before we graduated. We wanted to create a community for our peers and build the place we wanted to see, and this was the best way.

Installation view of Jon Rafman, The Age Demanded at Golden Age, courtesy of Golden Age, photograph by Karly Wildenhaus

NK: So you have this serious bibliophile background that seems to get to breathe a little bit more in filmmaking. How did your experience as a store owner shape you? In Monkey, there is such a dizzyingly broad range of references, in the film and its contextual frame, the Monkey Reader that accompanies it: a curated book of essays and stories from authors like Edward Said, Fran Ross, and Junot Díaz, and their works that inspired you.

Marco Kane Braunschweiler, Monkey Reader, 2017, 120pp, Edition of 50

MKB: I learned the value in working closely with a group of people that you know and trust, that’s everything. Golden Age’s inventory was entirely consignment and submissions at the beginning; it was a zone for bibliophiles, and also a super open space. A mentor of mine, business professor Bob Brodsky said, “An open door is an open door.” It’s a business tactic and a funny ouroboros-like statement. So we always kept the door open. It was not a place for everyone, but it was a place for anyone. That period was a time to test things out, to learn about my interests, to build knowledge and a peer group.

Exterior of Golden Age, courtesy of Golden Age, photography by Marco Kane Braunschweiler

NK: And then what happened when you moved to Los Angeles?

MKB: I shifted my focus to making videos. Filmmaking is writing, cinematography, sound, and editing… like a store, it needs lots of people. I just think about film as a format. Videos are a format. The photo is a format. Publishing is a format. Books, film, the internet, it’s all new media. Books are the oldest new media.

NK: There are so many points of entry into Monkey. There are technical questions of filmmaking, thematic questions, and then the universe of references, from Arthur Jafa to Oreo by Fran Ross. You’ve described Monkey as loosely based off of Ulysses, a canonical text. Was Monkey meant to challenge or poke holes in the canonical work that is Ulysses (which is itself parodying Homer, in an overturn of classic narrative)?

MKB: I spent time with Kerry James Marshall earlier this year, and he talks about mastery, about perfecting a craft. For me, Ulysses was the bar for European literature, which was a focus. And I identified with the book. I was Stephen at one time, and I thought that’s who I was when I started—an angry, emotionally dejected poet. In the course of making the first act, I realized that’s still there, but I’m more like Leo… peaceful, focused, caring and comfortable with who I am in all of my eccentricities and inconsistencies. I mean, I make a green smoothie every morning, I did not do that in my 20s…

Working on this project has been cathartic, and a learning process. Recently I lost an important partner, a family, everything. I’ve been reconsidering my values and why I think the way I do. Before, but especially in 2017, it’s an obligation to focus on work that is not white, European and male. I’m not trying to overturn or poke holes in these texts; I want Monkey to be considered on its terms, outside of the stacks of “canonical” works of European and American literature, which are in and of themselves, provincial texts. That’s one goal, to help poke holes in the concept of “Western” works as “canonical” work.

When I think of what’s “historically significant” work I think of how Dipesh Chakrabarty defines historicity in Provincializing Europe (recommended to me by a friend, artist Kelman Duran), he says, “In order to understand the nature of anything in this world we must see it as an historically developing entity, that is, first, as an individual and unique whole—as some kind of unity at least in potentia—and, second, as something that develops over time.”

That’s how I’ve been trying to consider the references I draw from and what I make. The time we’re living in is so unique, so brutal, and full of potential, that’s what Los Angeles is for me, especially as I continue to learn about it. It was important for me to bring together many different influences in the film, particularly in terms of mapping parts of MacArthur Park (named after an army general), and Pico-Union where I live now. Los Angeles is not a monoculture. What I thought was really interesting about Ulysses is how it depicts a hyper-specific experience. This is a person, mapping the place he lives in with an artwork. Making a film that is similarly focused, while not portraying a singular monoculture, is exciting to me. I want Monkey to be a re-envisioning, that shows the ever-present shadows that make up the political realities of “historic experience.” The way I’m trying to do this is involve, and show the people in my life. Nicholas Zhu, who plays Stephen is a brilliant artist, Jheanelle Brown, the narrator, is an amazing film programmer, artist Luke Fischbeck is there, my grandmother is there, Kelman Duran’s music is there, the film is a way to show the people who are in my Los Angeles.

NK: This film is defined by its flow, its forward movement-on skateboards, while driving. I think of how driving in Los Angeles is written about as a romantic act, switching people immediately into a kind of internal dream state. There are whole YouTube communities dedicated to driving in Los Angeles and driving in Grand Theft Auto’s Los Santos, for just that effect. Switching into the flow of one’s thoughts. Driving is key to your films, as in One Wilshire to Ocean Avenue. Could you talk about driving through the city and what it does for you, and why it is important to Monkey?

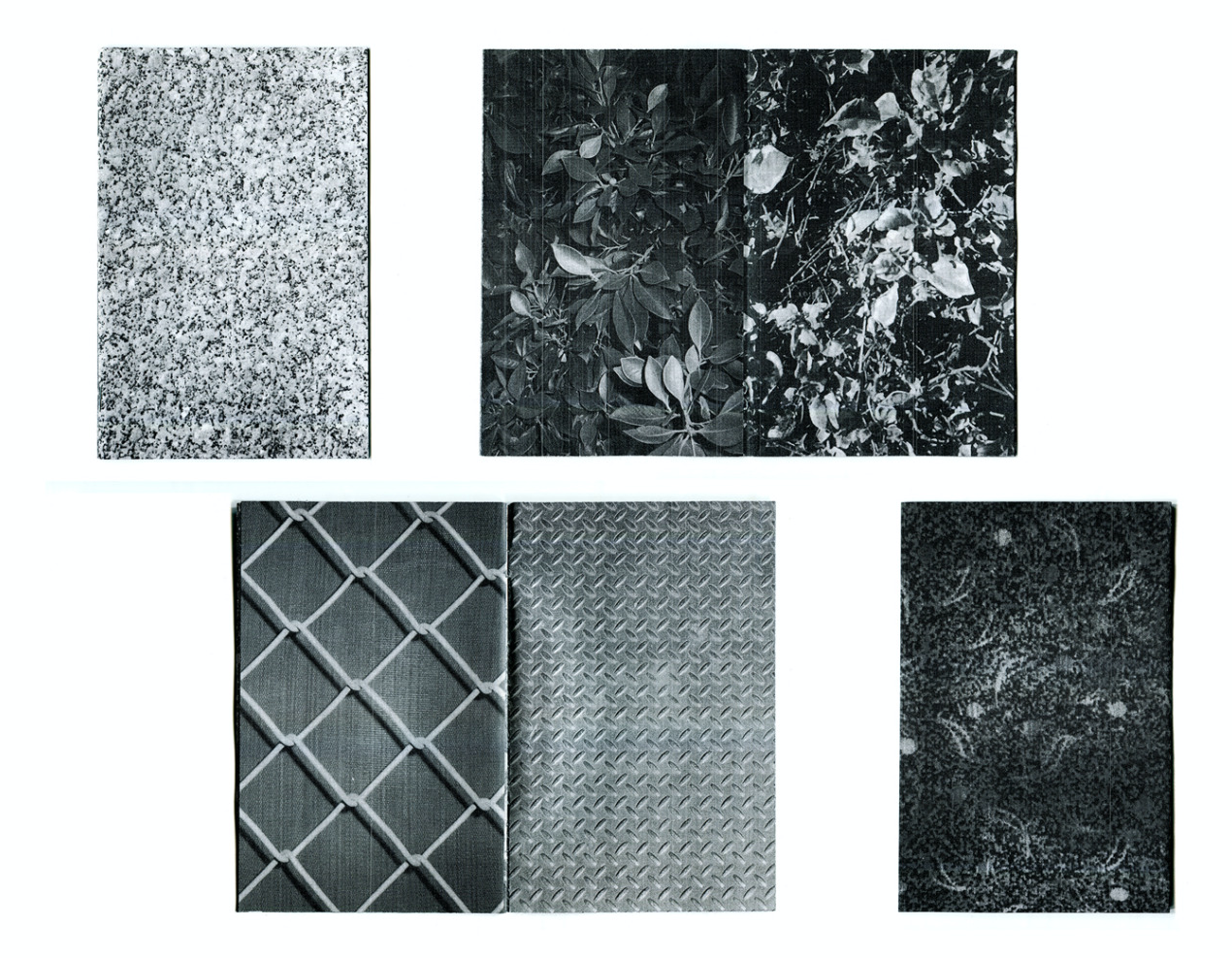

MKB: I think about the car or skateboard as a dolly. They’re the best way to do the valuable work of documenting the cities’ constantly changing architecture and planning. Architecture, like film, is a document of social history—reading it reveals so much about how we live. There’s not a lot of documentation of city architecture outside of Google Street View, whose authorship is part of a pantheon of corporate surveillance, which is not visually interesting to me. It feels really ominous when I see the vernacular sign rendered by Street View.

Marco Kane Braunschweiler, One Wilshire to Ocean Avenue, 2015, HD video, dimensions variable

NK: People talk about driving in Los Angeles like East Coast people talk about the weather. Robert Irwin constantly talks about driving in his interviews. Driving is the way he thinks, maps and accesses the city, and further, his thoughts. As I work on a manuscript based in Los Angeles, driving is the happiest I am there. It forms my best memories. It’s a ritual trigger for dreaming.

MKB: Absolutely. Paul Sietsema who I worked for when I first moved to Los Angeles, would talk about how he would pick his film up in Burbank, instead of having an assistant do it so that he could drive. Driving is an intentional and focused use of time and space. In my films, being a passenger is the effect of movement, and that turns the experience into a meditative space for thinking.

NK: Monkey feels like a story of how one might get through a day in the city with one’s body intact. You offer the viewer intimate glimpses into the maintenance work does it take to keep a body moving through space, to keep sanity intact. You have a series of time-lapse videos of stargazer lilies opening, from three years ago, and I trace the through-line from those videos to Monkey as one of the value, the significance of everyday rituals. The tiny choices that build up to making a life.

At the film’s pre-screening in Upstate New York, the audience focused on what it meant to have all these seemingly banal details of a day rendered so finely. Getting up, peeing, showering, examining a wound on one’s leg, rubbing coconut oil into the wound. Making a smoothie, buying bananas, getting a tortilla. Similarly, nearly every single act is detailed in Ulysses, from going to the bathroom, to all the graphic details of the body’s aches and pleasures. What is the significance of these daily private rituals? Seeing it all on film feels benign at first. Then you push us to keep watching. You realize the camera is going to insist on these small acts, just as the characters do.

Timelapse 12, 2014, HD video, dimensions variable

MKB: We all wake up every day, some place. Until we don’t. The two things that I think about every day are one, being in my body, and two, being dead. All these experiences are bodily. You wake up; that’s a bodily experience. You eat, and that’s a bodily experience. You feel the effect of the food. You get into the car. You feel the engine moving ever so slightly. Then you’re passing through space. On the other side of that bodily experience, there is death. That is the unknown.

The films are navigating the space between the known and the unknown. One Wilshire begins at sunset and closes on a dark beach. For me being a successful artist is pointing to things that cause people to think about their lives in a way they hadn’t before. I’ve just become very aware of how unique my experience is, and then by proxy, how unique everyone’s experience is. Everyone wakes up some place and goes to sleep some place, but no one else can have the experience that you or I have during the day. Through that specificity, I feel like there’s still a universality.

NK: That’s really poignant. Despite that universalism, Monkey feels extremely American, especially as I read Oreo by Fran Ross, which you’ve included as a reference. That story is mesmerizingly singular on the sentence level, but overall creates a pastiche, a language that is American, melting down dozens of genres. There’s a lightness, humor, and ingenuity, in a thin layer on top of a foundation of grotesque bullshit… all the massive structural and historical problems rooted in sexual, racial, and class violence.

When I think of great, classic American film and fiction, there’s this perverse irony we embrace culturally, the mania of how we manage to push on. Like building a little matchstick house on top of an abyss. We feel this vast and terrifying history underneath us. And navigating the city, you’re walking on ghosts, and dead people all day. Does this resonate with your framing of Los Angeles?

MKB: That’s the wildest thing about Los Angeles for me, it’s being built, and rebuilt, over and over. It is constantly shifting and moving. The market in MacArthur Park that’s between my house and studio has totally changed in the last three months. My interpretation of the sonic and visual elements of that place as it was are in Monkey. To me this is all part of a larger matrix of society, economics, culture, technology, and politics that is more easily responded to expressively, but remains impossible to ethically “map” from my position.

You talk about ghosts, and the ghosts and the history of space, being able to feel those presences. I think that as long as you’re attuned to that place, and as long as you’re aware of those experiences, you can communicate that through writing, video, or photography.

The complication is in the lens. The lens was developed as an ethnographic tool. This is a history that I really try to reckon with, especially as a white, male author. For me, that understanding allows me to be more aware, and give a depiction of spaces I’m not familiar with that is kinder. The dynamic of filmmaking is inherently adversarial. No matter how comfortable people are with cameras, it’s still a capture device.

NK: Do you feel a responsibility to capture Los Angeles, its local changes, through that capture? It’s unavoidable to think about what is lost in Brooklyn—the façades change from week to week. It affects the psyche. In Los Angeles, particularly, it feels difficult to get a sense of the history. So many futuristic films are built there.

MKB: On a very practical level, most of the construction here is with wood studs. In Chicago, all of the construction was with metal studs. Think about wood versus metal, and their permanence and durability. Los Angeles offers a totally different built environment and experience.

In One Wilshire, you take a trip down Wilshire, which is a street that’s named after socialist billionaire real estate developer Henry Gaylord Wilshire. That is incredible to me. You go from the biggest data center on the west coast, called one One Wilshire (which is actually at 634 South Grand Avenue!) to the end of the United States at the Pacific Ocean.

Between all of this you have numerous five-story developments for people working downtown, you have Koreatown, a center for investment, stuffed with high-rises. You have West L.A.–that’s what feels futuristic about Los Angeles, how many different experiences you can have in one 15 mile drive.

Marco Kane Braunschweiler, The Architectural Digest 2, 2016, 16pp, Edition of 100

NK: And being an outsider, moving from the Midwest, what did that do for you psychologically, to have everything be suddenly modular? In terms of making work and thinking about film?

MKB: For me it’s really freeing. It’s no longer about one singular “perfect” depiction but about mastering what I do and how I do it. In Chicago, I worked at an architectural photography studio called Hedrich Blessing, they’re responsible for how we see architectural modernism. Jon Miller hired me; he photographed Mies van der Rohe’s buildings, he’s who taught me how to build a kit, taught me how to use a 4x5. It was a very clinical, very tough job for me and I learned a lot. In Los Angeles, it’s been very different, it’s about exploring the spaces, and experiences of everyday life. The architecture is about those vernacular spaces. My friend Jerome Byron Hord told me that you don’t have to be an architect to submit a plan to the city. That’s why you can build so idiosyncratically in Los Angeles, and there’s a constantly shifting reinterpretation of space, that feels like how I approach making film here.

Marco Kane Braunschweiler recommends:

- My upcoming solo show at Human Resources opening September 18-24.

- Marco’s Island, my talk show on NTS Radio

- Jennifer Saparzadeh’s films

- Provincializing Europe by Dipesh Chakrabarty

- This interview with Edward Said

- Name

- Marco Kane Braunschweiler

- Vocation

- Visual Artist, Publisher

- Fact

- Marco Kane Braunschweiler is an artist and publisher, based in Los Angeles. He primarily works in video, and is interested in technology, historiography, and literature. From 2007-2011 he directed Golden Age, an artist-book store and project space in Chicago. He has presented programs at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Art Institute of Chicago and White Flag Projects, St. Louis. He has a radio show, Marco's Island, currently on NTS Radio. He has exhibited at the Swiss Institute, New York; 356 Mission, Los Angeles; Human Resources, Los Angeles; the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago among others. His work has been written about in Artforum, Hyperallergic, and published in the New York Times. He describes his film Monkey as "a docufantasy, set in Los Angeles, about two people growing close, and two people falling apart. You could say it’s an epic, a buddy movie, a family drama, or, indubitably, a downright freak-fest. The video takes place on Christmas day, in the year 2017 and the narrative is from the pages of Ulysses. It’s a winding, Homeric tale that chronicles the long, tender journey from loneliness to solitude."

Some Things

Pagination

Marco Kane Braunschweiler interviews

Marco Kane Braunschweiler interviews