On leaving a trace

Prelude

Heryte Tefery Tequame is a Harlem-based photographer, editor, and cultural producer. She dreams up digital ecosystems centered on contemporary art practices, in-flux archives, and infinite content. As an American, French, and Ethiopian woman whose existence is nestled in overlapping histories, her practice emphasizes a multilocal and multi-layered approach to Black and diasporic existence. Heryte is currently a Curating Editor of Flaneur Magazine’s ninth issue and the Queens Museum’s Assistant Director of Communications and Digital Projects.

Conversation

On leaving a trace

Photographer and cultural producer Heryte Tefery Tequame discusses capturing a moment, her Instagram artist residency program, and the internet as a spiritual practice.

As told to Grashina Gabelmann, 2211 words.

Tags: Photography, Culture, Inspiration, Identity, Process.

Do you see yourself as a photographer and curator?

Right now, I see myself mainly as a cultural producer, because I think “curator” has a lot of baggage in the way the word is used. As a cultural producer, I can curate, but I also take on other roles that help bring cultural projects to life.

When I look at your photography, at first I see a lot of humor and tongue-in-cheek-ness; looking at it longer, though, more depth arises as well as sadness and I become curious to know what happened for that object to be there on the street and who put it there. This second layer of emotions reveals itself only after a moment and I find it beautiful.

My photography is at the intersection of documentary photography and street photography. It doesn’t fit into any of those boxes alone, just because the way I approach it is really about capturing objects in public space, and not necessarily as still lives. It’s more about capturing human presence through objects that have been left behind. Understanding a city, understanding a moment, understanding who has been there, and who has left through the objects that remain. The way that I shoot objects is really about projecting towards the moment that led them to be there, finding human essence in what remains. The moment is there, and it has revealed itself, and I’m just here to capture it. By capturing it, I think I open the door for imagined possibilities of “What was that moment?” A lot of people have told me there’s a bit of ghost-like presence in the way that I shoot things. The only way those images were able to be captured is through being alone, which is how I’ve experienced cities a lot of the time.

You started a digital residency on Instagram.

Yes, SHEGITU.SSR, which was an opportunity for me to think about how social platforms could be used as artistic mediums. And now it’s shifted with COVID but in a pre-COVID time, there wasn’t much art being made for social media. So, I was really interested in inviting artists to approach the Insta square and Insta space as a residency space and as a medium taking into account the limitations of the platform in their art making, and taking into account the tools that are inherent to the platform and to think of sharing as exhibiting, and saving something to your collection as becoming a collector of that work without the transfer of money. If we’re using Instagram, and Instagram is something that everyone uses all the time, maybe it will make art more accessible. Maybe people will be interested in owning art, because they don’t have to buy it. And it can just be something that they can look at in their own personal Instagram collection.

You’re interested in thinking about art through the lens of social media, these platforms that are so embedded in our daily lives.

Yeah, and then, with COVID, suddenly everything was about those digital platforms. That’s how we were connecting and how we were going out in the world when we couldn’t physically leave our homes.

And then with COVID came a lot of loss. Suddenly these platforms became spaces to mourn collectively and to engage in spiritual practices collectively. How are Instagram or Zoom becoming places of spiritual practice? And not necessarily just replicating traditional practices but also thinking about practices beyond what’s considered acceptable to the more institutional religious spaces. I wrote a proposal for a show around these topics. There are some artists that I’ve been interested in for a long time, who kind of push that, like Seumboy Vrainom, who considers himself a digital shaman.

So this intersection of spirituality and spiritual practice interests you?

Yes. There’s considering the platform itself as a god-like entity, but there’s also using the platform itself as a vector for spirituality. There’s this text that I read when I was working on a proposal, which was an essay by Joanna Sleigh. She looks at the Church of Google, which is a group of people who honor and venerate Google because they believe it’s “the closest thing to a god that can be scientifically proven.” In that church there are people who believe that Google is god, just because it is omniscient. And when you think of that omniscience, the fact that it’s both everywhere and nowhere, these are things that we really associate with god or gods. Then there are people in the Church of Google who want to show how Google can be a god so that they can also show how institutional religion isn’t as justified as we think it is and that different things can be considered the objects of spirituality.

And that goes back to your interest in investigating how we use our daily tools in other ways than they are meant to be used.

Yeah. One of my close relatives passed away very recently. We would generally keep in touch through WhatsApp and now, when I go to our WhatsApp chat, there’s the time mark of the last time they were active on the app before being hospitalized, you know? And it’s sort of like “last seen on” and I see that, and I find it both beautiful and scary. Beautiful in the sense that it is a kind of lasting trace. Maybe that was their last digital breath, like the last time they were in the digital world and that’s the timestamp. And it’s also just so ghost-like because that’s almost like the last trace of life. When I see it, it’s almost as if they’re still here.

So, back to my proposal. I think the proposal came out of these questions, of all these tools seeming kind of omniscient, godlike, but it also came from, as I said, just a lot of loss that we experienced due to COVID and police brutality, and how we’re in this constant state of mourning, but not able to engage in mourning in the ways we traditionally do, which is through the collective gathering of people.

There is this artist who works a lot with the digital sphere, her name is Liz Mputu. She created this half-an-hour-long memorial to Sandra Bland, a Black activist who was arrested and found dead in her jail cell in 2015. The work is an assemblage of different clips that are both taken from the internet, but also video footage of Sandra Bland herself speaking. And what I just found interesting about this piece is that it’s supposed to be a moment of grieving for people and a moment to release emotions in regards to the fact that no one was charged for Sandra’s murder.

And what about footage of people living on the internet for so long? Do these people really pass? It’s almost like they are still here. They are still present in those spaces we find ourselves in.

Spaces that are non-physical anyway.

Yeah.

So why would not having a physical body hinder them from being present in non-physical spaces?

For sure. Which is hard also, because it makes the process of grieving even more difficult. When you think about the video footage and photos of George Floyd, for example, circulating endlessly, to the point where it feels like a second life has been created for this person, without their direct consent.

I think choosing to be “forgotten” is also removing yourself from the ways you can be used beyond your consent after you pass away.

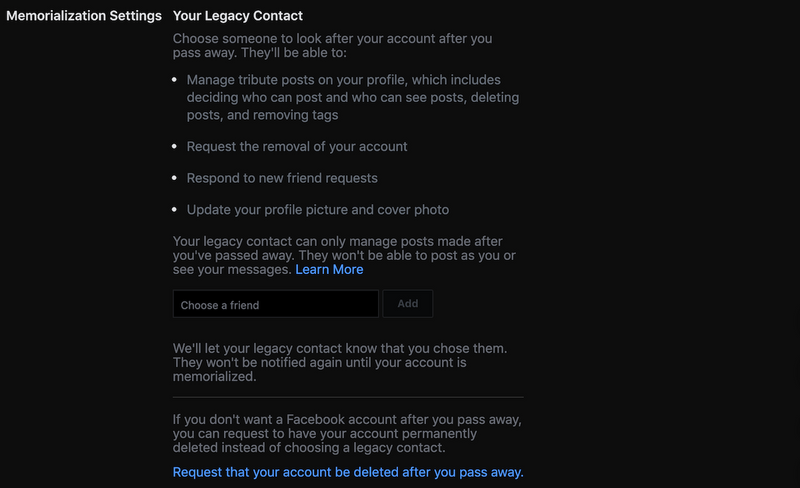

That’s something we haven’t regulated and has led to a lot of issues even. For example, when it comes to the Black Lives Matter movement, different individuals who have been killed by the police are now being portrayed as martyrs because of everyone being able to access their image and story and footage. It’s really about post-death consent onto your story, onto your image. Maybe, and ironically, Facebook’s “Memorialization Settings” might actually be one of the most accessible tools that we have in terms of giving or not giving consent before passing.

There is a need for more reflection on, how do we protect people digitally? How do we protect people’s consent digitally once they’re gone?

Yes, and that’s the kind of double-sided thing, where it’s like, on one hand, I’m grateful for these tools and platforms because they allow people to be accessible to us and be present in our lives once they pass away. But on the other hand, that comes with a dark side, as to people being able to do what they want with whatever remains online.

And all of this is connected to the shamanistic world. There isn’t really a difference. Just because it’s digital doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a spirit. We probably do have spiritual digital selves.

I think that all these digital platforms have allowed for a reaffirmation of spiritual practices that haven’t benefited from the visibility of more institutionalized ones, and made them more accessible to people. Whether it be shamanic practices, or even just thinking about astrology, and how that’s just been such a big thing now. People have always been into astrology but it wasn’t as accessible. Now I check my horoscope every morning after waking up. That’s almost a way of starting the day on a spiritual level.

Yeah, it’s a ritual.

It’s a ritual. I think any ritual in itself is a form of spiritual practice, in the sense of repeating things, whatever it may be. It is a way of setting the tone for the energy you’re putting out into the day. So beyond it being astrology, it’s also just like that intention has its own spiritual potential. Choosing to do this every morning and understanding how that’s going to set the tone for the day.

Going back to the topic of consent in terms of digital stuff, which images get used for memes is very fascinating.

Yes. Despite your will you can become a cultural icon and a cultural asset in such a short amount of time. I think about 9GAG, early meme days and they were mostly just stock images. And okay, the people in these stock photos knew that they were going to get used, but they thought they were going to be on a flyer somewhere. I read an MIT publication about the meme and how it’s a cultural asset. And how there is a difference between virality and something becoming a meme. Something can be viral but it doesn’t mean it can become a meme. Something viral, like a video that is shared a million times, isn’t transformed in any way. Whereas a meme is something that originated in one form and that grows stronger and survives through transformation.

Like a virus that mutates?

Yeah and each mutation is like an intervention on the meme. So when it’s appropriated by a new person who creates a new version of it, it’s still based on the same meme principle and therefore allows it to become even more known.

Are memes a kind of ritual in a way, because they repeat all the time but also change?

It’s ritual plus adaptation and transformation that allows it to survive. For example, think of meditation. Meditation is such an ancestral practice. And there’s some people who I imagine meditate in its original form. But now there are a lot of people engaging with meditation and clearly it’s not in the same way as it was before. And the way that meditation has been able to survive, as a practice is because it’s also been adapted into ways that allow it to conform to people’s lives and routines. And you have meditation apps, you have meditation circles and because of its transformation that has been able to survive. It’s not just about popularity but adaptability and transformation.

And there is a risk with more people having access to something.

Yes. Through that transformation things get integrated that might not necessarily make sense and things get claimed by individuals or a culture where it might not make sense. And that’s also the difficulty with the internet: what belongs to whom and who can claim ownership over things. It’s tricky. That was the utopian vision at the beginning of the internet, it belonged to everyone. And that was kind of beautiful.

Heryte Tefery Tequame Recommends:

@yourfavoriteauntieshow, an IGTV talk show hosted by writer Marjon Carlos.

@manufactoriel, a research proposition in African & Black contemporary visual culture, art, and style.

@paajoewks, a living archive of coffins by Ghanaian artist Paa Joe.

@transplantationproject, a collaborative practice, an afrofuturist vision.

@somejazzplaying_, a mood.

- Name

- Heryte Tefery Tequame

- Vocation

- Photographer and cultural producer

Some Things

Pagination